Two white teardrops seem to leak out of my mouth. On my thigh a small heart rapidly develops and then, as unexpectedly as it appeared, explodes into a map of constellations. Half my right eyebrow turns white so that unless you look closely, it seems to have just vanished. In Khartoum, I'm just an odd person with odd skin. Nobody comments aside from an occasionally politely curious, "So – what is that?"

I have vitiligo. It appears when I'm 13, white lines emerging on my hands and causing panic about how to explain away what I think are scars without stories. As I practise a self-deprecating laugh ("I'm just so clumsy!") the patches begin to link up and it becomes apparent they're something else, something more. Vitiligo is an autoimmune disease where your body attacks the cells that create melanin, leaving colourless patches of skin. The Vitiligo Research Foundation estimates vitiligo prevalence at between 0.5% and 2% worldwide.

You probably know of vitiligo from Michael Jackson, or perhaps from one of the many articles on successful, beautiful people who struggled with and overcame the issue. Sometimes the solution is a masking cream that allows them to be "normal" again. Sometimes their vitiligo becomes a trait that is amplified, mutating from the cause of bullying into a high-fashion USP. Neither of these options resonate with me; this patronising assumption that vitiligo is something that destroys self-esteem, or is central to the everyday of my life, seems to feed into a wider cultural response to me as an individual. I resent being told that I "suffer" from my skin.

The first treatments I have for my vitiligo come with pressure from my parents. They tell me that without it I might struggle finding both work and love, because unfortunately looks count for far too much in this world. There are topical corticosteroids at the age of 14, and I am given permission to violate my school's dress code in order to wear sunglasses in class, because the ointment makes you more susceptible to developing cataracts. The next one is a foul herbal medicine bought from a Chinese massage parlour in east London while on holiday that I am guilted into drinking daily, despite the ingredients remaining a mystery to me. Links to experimental treatments are passed on from my father with a note that money will be found if need be. My parents, particularly my father, worry I won't be pretty. I say I don't care and no one else does. I sit them down and say I'm not going to do this to myself – I'm happy with my skin as a living work of art – and so at 18 I arrive in London for university, full of confidence. By this time the teardrops have cascaded outwards and drowned my face in whiteness; my hands are white gloves and though I don't realise it yet, I have crossed a continental line that takes me from a person to a curiosity.

What happens when your skin betrays you, turns itself into a target for a collection of patronising views and disgusted looks?

First I must get used to the constant stares, every conversation beginning with a steady focus on my hands that drowns out what I say. There is the assumption that I am heroic for existing, even with my fair skin making my vitiligo less obvious than it is for those darker than I am. There is the assumption that it makes me inherently ugly, so kind people lean in and say "someone special will look past that" as if no lover could appreciate or even enjoy the evolving canvas. In the first month a woman approaches me and tells me I "shouldn't hate my race". I say I'd like to think if I bothered to bleach my skin I'd be far more efficient at becoming white. Another lady yells from across a different room that I am a racist, convinced that my mind has somehow forced my internal bigotry upon my skin.

Perhaps I could have brushed these new intrusions off as outliers, a slight increase in life's daily annoyances. On the tube and on the streets I become aware of people leaning in, trying to get a better shot with their phones. A snap is taken of my hands, the screen briefly flipped to a friend, before it is sent out. People say I'm paranoid – "nobody would do that!" – and so I start two columns in my diary: suspected photos, and certain photos (confirmed by reflections in glass or a quick look at the screen). I don't know how to say "stop" over and over again, so I make a mental note to buy gloves. Eventually I get some. They are brown leather, the colour of my dad's skin, and many multiples darker than my own.

I learn to notice the constant undertone in every interaction; my skin is a thing to be addressed. It is draining to be a curiosity when you just want a conversation. After all, what is more immediate than skin? And so despite my love for my vitiligo, I feel that if I could just regain that deep universal tan I could successfully pass as myself.

The doctor at St. Mary's in London asks me to come in, speaking farsi as I enter the room. She does this every time I arrive for an appointment, and each time I will gently correct her in English. Over the course of the year I begin to suspect that she feels I should just commit to learning farsi if I'm going to go about looking vaguely Iranian. After a few months of waiting I now have my first photo-dermatology appointment, and am passed a sheet to sign, accepting a series of rules: I must avoid the sun as well as "radical" haircuts (layering or big changes in length during the process reduces protection of the scalp), and I cannot wear jewellery, perfume, lotions, or make-up on the days I have treatment, otherwise I may get severe burns.

After, I am led into a small room and asked to strip to my underwear. The small blonde nurse draws a thin curtain that doesn't quite make it to the wall and produces a small pad featuring two outlines of a sexless figure. There is no budget for a camera to accurately measure progress, and so instead she stares intently at my body and sketches. She recommends taking photos at home as they will be a better comparison. Just when I begin to feel really self-conscious she interrupts my thoughts: "Can you describe your genitals and breasts for me?"

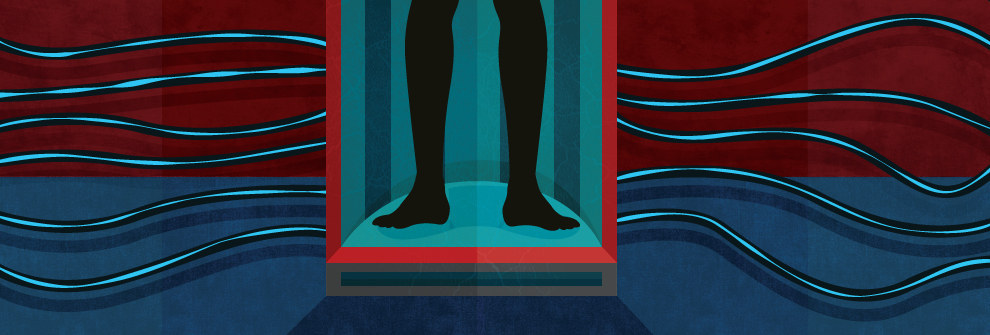

The machine itself is essentially an upright tanning bed except it only emits UV-B light, (the rule of thumb is that UV-A ages and UV-B burns). I enter a box lined with long tubes pulsing blue light and stand naked, feet apart, arms raised straight, with thin blue goggles on my closed eyes. The nurse comes by, clicking the door shut, and at 15 seconds an alarm sounds and I'm done. Each following session is slightly longer and exposes me to slightly more UV-B radiation.

Twice a week I trade my regular mornings for this ritual, and every few months there is another self-assessment. They want to know if I don't leave the house because of my skin condition, or if I hate myself because of it. All my answers stay the same, stay unrelentingly positive about how I look and how comfortable I feel taking part in the wider world. There is minor confusion on their faces as they read each answer, an unspoken, Why are you doing this, then?, and I begin to add small clarifying notes explaining my perspective that this treatment is to minimise the constant barrage from strangers. "Went out but had to deal with intrusive questions," I write, "although did not affect my confidence level."

"It will change your definition of beauty." That is what the articles and videos tend to promise. It implies the truth – that without reaching that cultural touchstone of beauty you are treated as less than. It's why there are camouflage clinics in London, places where you can get theatre-style make-up to avoid that break in your visible armour. On my way to one a man sits across from me on the train and puts down his newspaper to ask what happened in the fire. I toy with refreshing my high school drama skills and conjuring up a vast tragedy, but opt instead for "Oh, nothing" and staring out the window.

I learn how to disguise myself with tubes of cream, but it looks a little flat, costs a lot, and when I get home I get as far as shading in my eyebrow. The symmetry is wrong. There is so much value in this service, but the biggest reason for that value is that our society itself is so terrible. I've experienced a place where my vitiligo did not invite this constant barrage. With the make-up I feel foreign in my own skin.

Why is there such a difference between Khartoum and London? Perhaps in a Khartoum society that values light skin over dark, my fair-skinned Iranian-looking complexion is more valuable so that even its new patchwork quality can be ignored. Maybe the Arab-looking stranger in London is different enough that the vitiligo just highlights that difference even more.

As the dosage of my treatments increases in intensity the burning becomes more frequent and more areas are protected in the machine. I now stand naked wearing what can only be described as a riot policeman's head shield, gardening gloves, and thick sunscreen on my breasts, one of which is still a deep red from the month before when I forgot to cover it fully. The nurse pulls me to one side. I have reached the halfway point for my lifetime limit: Would I like to pause at some point to preserve them? I have had 100 sessions, reaching 1.23 joules per treatment, with a cumulative dose of 104.16 joules. There is some re-pigmentation, but I have also acquired half-moon scars under each breast, the result of shifting my arms in previous sessions. I have a slightly raised risk of cancer.

I still can't quite grasp that my identity as a "normal" person is obscured by a process of my own body. That even with my confidence, for a broad swath of people I will always be a "sufferer" or a "freak". People won't stop. But I can. I tell the nurse I'm done. I am fortunate. For others there may be no such choice. This treatment may well be the best way to get through the day. Later that week on the Northern line, I sit across a carriage from another person with vitiligo. We share a brief moment of respite, a moment in which a cursory look isn't something loaded with negative feeling. I think I made the right choice.