-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A Burcu Bayram, Catarina P Thomson, Ignoring the Messenger? Limits of Populist Rhetoric on Public Support for Foreign Development Aid, International Studies Quarterly, Volume 66, Issue 1, March 2022, sqab041, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab041

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The negative impact of populist anti-aid rhetoric on public opinion has been based on anecdotal reports to date. Here, we take a systematic and empirical look at this inquiry. We hypothesize that even though populist rhetoric decreases support for foreign development aid in donor publics, this effect is conditioned by individuals’ preexisting beliefs about populist leaders. Using data from original survey experiments conducted with representative samples of American and British adults, we find that exposure to different variants of populist frames decreases individuals’ willingness to support their government providing development aid through an international organization. However, this effect is moderated by whether people think populist leaders stand up for the little guy or scapegoat out-groups. Connecting foreign aid and populism literatures, our results suggest that the future of global development might not be as bleak as previously feared in the age of populism.

El impacto negativo de la retórica populista contra la ayuda en la opinión pública se ha basado hasta ahora en informes anecdóticos. Aquí analizamos de forma sistemática y empírica esta cuestión. Nuestra hipótesis es que, aunque la retórica populista reduce el apoyo a la ayuda exterior para el desarrollo en los públicos donantes, este efecto está condicionado por las creencias preexistentes de los individuos sobre los líderes populistas. Utilizando datos de experimentos de encuestas originales realizados con muestras representativas de adultos estadounidenses y británicos, encontramos que la exposición a diferentes variantes de marcos populistas disminuye la disposición de la personas a apoyar a su gobierno para que proporcione ayuda para el desarrollo a través de una organización internacional. Sin embargo, este efecto se ve moderado dependiendo de si la gente piensa que los líderes populistas defienden a los más pequeños o convierten en chivos expiatorios a los grupos marginales. Al relacionar las opiniones sobre ayuda exterior y populismo, nuestros resultados sugieren que el futuro del desarrollo global podría no ser tan sombrío como se temía anteriormente en la era del populismo.

Jusqu'ici l'analyse de l'impact négatif de la rhétorique populiste anti-aide sur l'opinion publique s'est basée sur des rapports anecdotiques. Ici, nous étudions cette question d'une manière empirique et systématique. Nous émettons l'hypothèse que bien que la rhétorique populiste réduise le soutien à l'aide au développement étranger chez les publics donateurs, cet effet est conditionné par les convictions préexistantes de l'individu concernant les dirigeants populistes. Nous nous sommes appuyés sur des données issues d'expériences d'enquête originales menées auprès d’échantillons représentatifs d'adultes américains et britanniques, et nous avons constaté que l'exposition à différentes variantes de cadres populistes réduisait la volonté des individus de soutenir leur gouvernement dans la prestation d'une aide au développement par le biais d'une organisation internationale. Cependant, cet effet est modéré selon le fait que les individus pensent que les dirigeants populistes se dressent pour les « petits » ou désignent les groupes marginaux comme boucs émissaires. Associant les littératures sur l'aide au développement étranger et sur le populisme, nos résultats suggèrent que l'avenir du développement mondial pourrait ne pas être aussi morne que l’ère du populisme pouvait auparavant le laisser craindre.

Introduction

Aid agencies, foundations, and aid-friendly governments worry that populist politicians’ anti-aid rhetoric is impairing the already tenuous public support for foreign development aid in donor countries (e.g., Inglehart and Norris 2016, 2017; Jakupec and Kelly 2019; Mueller 2019; Thier and Alexander 2019).1 However, this concern is largely based on anecdotal reports. To date, the effect of populist anti-aid rhetoric on public support for foreign development aid has not been systematically and empirically analyzed. We undertake this task.

Much like traditional models in economics, in the populism literature scholars distinguish between supply and demand characteristics. Supply-side theories of populism focus on the efforts of populist politicians and parties to influence and mobilize citizens. In contrast, demand-side theories of populism focus on individuals’ preexisting populist attitudes and their level of support for populist politicians and parties, claiming that populism is not merely a product of political entrepreneurs, but rather that populists tap into latent populist predispositions. Marrying supply and demand theories of populism with insights from theories of public opinion formation, we argue that while exposure to right-wing populist anti-aid rhetoric decreases support for foreign development aid, this effect is conditioned by individuals’ prior beliefs about the intentions and trustworthiness of populist leaders.

Evidence from survey experiments fielded on nationally representative samples in the United States and the United Kingdom (UK) supports this claim. We find that exposure to populist anti-aid rhetoric focusing on the will of the common people, corrupt and manipulative elites, and the well-being of the in-group diminishes support for foreign development aid, measured as multilateral aid to UNICEF. This effect is relatively small in the general population, yet considerably large for individuals who think populist leaders protect the interests of the common people. Individuals who think that populist leaders “stand up for the little guy” are much more susceptible to populist rhetoric than those who believe that populist politicians “scapegoat out-groups” for national problems. Even though populist rhetoric can reduce support for foreign development aid channeled through international institutions, the largest negative consequences are for those already predisposed to support populist figures to begin with. Our results are robust to an array of controls and robustness checks. The most important policy implication of our results is that the future of foreign development aid might not be as bleak as one might fear in the era of populism.

Boucher and Thies (2019) argue that “[r]ather than debate what populism is, or how it differs across regions, we may profit more from a focus on how populist rhetoric structures debates about important foreign policy issues …” Our research is guided by this recommendation. Conceptual debates regarding exactly what populism is (and is not) are no doubt important to the discipline. However, our contribution is more circumspect as we focus on populist rhetoric, rather than on populism more broadly as a concept. Our goal is straightforward: we examine how common manifestations of right-wing populist rhetoric influence public opinion on foreign development aid. Opposition to foreign development aid is, of course, not the only component of populist politics. Its prevalence in many settings, however, makes the link with public opinion worth further exploration.

There is little question that developing countries that rely on official development assistance, aid agencies and foundations, and international organizations are worried about the resurgence of populism that is hampering foreign aid and global development cooperation. Some go as far as to consider the surge of populism as the end of neoliberalism (Jakupec 2018; Peters 2018; Puehringer and Oetsch 2018). And there are grounds for concern: suggested or actual cuts to foreign aid by populist parties and the “my country first” attitude of politicians who have adopted populist policies directly threaten development cooperation. For example, during his time in office Trump proposed deep cuts (about 21 percent) to foreign aid spending every year he was in office (Morello 2019). In June of 2020, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the Department for International Development (DfID) would be subsumed by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, arguing that this move ensures aid funding can be used to support national strategic objectives rather than being constrained by a narrow focus on poverty reduction (Chalmers 2020). In Australia, Tony Abbott reduced the aid budget by $11 billion in 2015, stating that “if you don't have your domestic economic house in order, it's very difficult to be a good friend and neighbour abroad” (Wahlquist 2015).

Of course, the anti-aid stance of populists is only one piece of the larger globalization backlash that includes anti-immigration and protectionist trade policies and the redefinition of foreign policy to serve the parochial interests of the nation. Foreign aid is not unique in this sense, and the distributional consequences of foreign aid might be less visible than those of trade or immigration for voters.2 However, foreign aid is one of the key elements of the populist playbook. This is because unlike traditional fiscal conservatives, populists do not simply wish to reduce aid spending; they seek to redefine the purpose of aid and development cooperation to serve their countries’ economic and political interests.

Populists will often set out to use foreign aid to limit the numbers of immigrants and refugees, sometimes going as far as to include plans to resettle them back to their countries of origin. The foreign policy manifesto of the British National Party (BNP), for instance, notes that “only once poverty and deprivation amongst British people has been eliminated, can any thought be given to foreign aid—and even then, a BNP government will link foreign aid with our voluntary resettlement policy, in terms of which those nations taking significant numbers of people back to their homelands will need cash to help absorb those returning.”3 The 2017 manifesto of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) similarly states that “development aid and visa policy should be used as incentives to foster the willingness of foreign governments to co-operate in the repatriation of their nationals.”4

Another reason foreign aid has become a tool in the populist playbook is that targeting foreign aid allows populists to conveniently appeal to voters’ feelings of being left behind by economic liberalism, multilateralism, and globalization. Since many people already overestimate the amount of aid spending, it is expedient for populists to go after foreign aid as a cosmopolitan policy that has prioritized “foreigners” at the expense of “patriots.”5 For example, although the non-populist center-right conservatives in the UK still want to reduce foreign aid spending, in their 2019 manifesto, they do express a commitment to “peace-building and humanitarian efforts around the world” and “to Britain's record of helping to reduce global poverty.”6 Populists do not express these cosmopolitan goals. The 2019 manifesto of the United Kingdom's Independence Party (UKIP), for example, clearly states that Britain should return to the old system in which the DfID was a small directorate of the Foreign Office responsible for disaster relief only and on an “as and when” basis.7

Finally, in some cases, the anti-foreign aid stance of populists moves mainstream conservatives further to the right given popular support for populist parties. UKIP's Suzanne Evans famously quipped on a BBC news comedy show that UKIP did not need to win seats since recently the Conservative party had been implementing their policies for them.8 Indeed, the Johnson government announced in mid-November 2020 that the UK will renounce its commitment to spend 0.7 percent of GDP on foreign aid.9 Johnson's provocative rhetoric (including referring to legislation aimed to block a no-deal Brexit as “the Surrender Act”)10 and ostensibly populist tactics11 are transforming the Conservative party.12 Prominent MPs (including two former Chancellors and Churchill's grandson) have left the party or been expelled by Johnson in the infamous “Tory Remainer purge” of 2019. Former Conservative Justice Secretary David Gauke was among those who claimed the purge was designed to “‘re-align’ and ‘transform’ the Tories ‘in the direction of The Brexit Party’”13,14 and campaign as such in a snap general election.15 The “people vs parliament” election campaign16 arguably worked as Johnson secured the largest Conservative majority since the 1980s. Johnson himself acknowledged winning “with borrowed votes” from many who had never voted Conservative before.17

Given the importance of foreign development aid in populist politics, the relationship between populist anti-aid rhetoric and public attitudes is worth further investigation. This research makes three main contributions to existing scholarship. First, we directly examine the impact of populist anti-aid rhetoric on support for specific foreign aid policies, bridging foreign aid and populism literatures that have to date remained disconnected. Despite a handful of recent exceptions (Bos, Van der Brug, and de Vreese 2013; Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese 2018a; Busby, Gubler, and Hawkins 2019), we still know little about how populist rhetoric affects support for specific policies. As Busby, Gubler, and Hawkins (2019, 1) note, “[t]he rhetoric of populist politicians is an important part of their appeal.” Scholars have examined the agendas of populist politicians (Ivarsflaten 2008; Inglehart and Norris 2017), populist voter mobilization (Mudde 2013; Immerzeel and Pickup 2015; Hawkins 2016), populist predispositions (Hawkins, Riding and Mudde 2012; Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove 2014; Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck 2016; Bernhard and Hänggli 2018; Van Hauwaert and Kessel 2018), and the impact of populism on international organizations (Copelovitch and Pevehouse 2019), as well as the definition of populism more broadly (Canovan 1999; Taggart 2000; Mudde and Kaltwasser 2012; Gidron and Bonikowski 2013; Seitz 2017). We for the first time offer evidence on populist rhetoric and mass foreign aid preferences using nationally representative samples from two important donor countries who have been caught up in the recent populist wave. In so doing, we speak to the broader field of international relations given the growing interest in the “international dimension of populism” that seeks to uncover the impact of populism on foreign policy (Chryssogelos 2017; Verbeek and Zaslove 2017; Hafner-Burton, Narang, and Rathbun 2019; Sagarzazu and Thies 2019; Wehner and Thies 2020).

Second, our research contributes to recent works on populism that suggest an interaction between individuals’ preexisting beliefs about populism and populist leaders and their policy preferences (Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese 2017, 2018b; Mueller et al. 2017; Hawkins, Kaltwasser, and Andreadis 2018; Busby, Gubler, and Hawkins 2019). By showing that peoples’ beliefs about populist politicians make them more or less receptive to populist anti-aid rhetoric, we highlight the interaction between demand and supply sides of populism.18 This finding also adds to the literature on the limits of elite cuing (Guisinger and Saunders 2017; Kertzer and Zeitzoff 2017), as elite cues appear to be more persuasive when individuals are predisposed to receive them and believe them in the first place.

Finally, we stand to contribute to the burgeoning literature on foreign aid and public opinion (Milner and Tingley 2013).19 Important works have demonstrated that foreign aid policy is responsive to public opinion (Mosley 1985; Lumsdaine 1993; Milner and Tingley 2010, 2011; Powers, Leblang, and Tierney 2010; Heinrich 2013). Even though public opinion may not directly affect aid allocations, politicians do care about the pulse of the public and seek to shape public opinion. Mosley (1985), for example, has shown that public opinion influences both the amount of aid and where aid flows. Powers, Leblang, and Tierney (2010) have observed that members of Congress are more supportive of foreign aid bills when their constituencies support it too and specifically when there are foreign aid beneficiaries present in their districts. Heinrich, Kobayashi, and Bryant (2016) have demonstrated that politicians cut aid during economic crises because voters place a much lower emphasis on foreign aid when the domestic economy suffers. Scholars have also shown that publics are mindful of the economic costs and benefits of aid (Heinrich 2013; Heinrich, Kobayashi, and Bryant 2016; Hurst, Tidwell, and Hawkins 2017), the effectiveness of aid and the deservingness of recipient governments (Bayram and Holmes 2019), the relationship between aid flows and trade relations (Hudson and van Heerde-Hudson 2012), and claiming credit for aid (Dietrich, Hyde, and Winters 2019). Our research adds to this growing body of work on public opinion on foreign aid by bringing in populism.

This paper unfolds in four main parts. First, we focus on the supply side of populism and hypothesize how frames of populist rhetoric impact public support for foreign development aid. We then turn to the demand side of the picture, specifying how previously held views on populist leaders moderate the effect of populist rhetoric on public attitudes. The next section explains our experimental intervention and introduces the data. We then discuss our findings and conclude by addressing their broader theoretical and policy implications.

The Messenger: Populist Rhetoric and Foreign Development Aid Preferences

What is populism and what are its effects? As noted by Bryant and Moffitt (2019), this question seems to be on everyone's minds, despite difficulties in agreeing on what the concept actually means (Canovan 1999; Taggart 2000; Gidron and Bonikowski 2013; Seitz 2017). Populism has been defined as a thin ideology (Mudde 2004; Mudde and Kaltwasser 2012), a political strategy (Weyland 2001; Madrid 2008; Acemoglu, Egorov, and Sonin 2011), and a communication strategy or discursive style (Laclau 2005; Hawkins 2009; Jagers and Walgrave 2007).

Despite populism being famously difficult to define, there is firmest consensus that Mudde's (2004) focus on thin ideology captures the essence of the concept. Adopting Mudde's approach, Mudde and Kaltwasser (2012) define populism as “a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic camps,” “the pure people,” and “the corrupt elite,” and argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people. The main advantage of a thin-ideology perspective is that it allows populism to take slightly different forms as it blends with thicker local ideologies in different national and institutional settings (Wehner and Thies 2020, 3). This is particularly important in cross-national studies of populism, as different populist leaders can highlight different aspects of the core distinction between “the people” and “the elites” in their rhetoric (as expressions of local populist ideologies).

As several scholars have noted (e.g., Kriesi 2014; Reinemann, Aalberg, and Esser 2016; Aalberg et al. 2017), “[w]hereas the populist ideology is a mental concept, populist communication is its manifestation (Wirz 2018, 15).” Populist rhetoric appears in political speeches, the media, and party manifestos as the expression of populist ideology “out there” in the world.20As such, we turn to Jagers and Walgrave (2007), who have offered an analytical framework consistent with Mudde and Kaltwasser's definition laying out the three most salient dimensions of populist rhetoric. Jagers and Walgrave (2007, 322) have identified three core dimensions of populism as “the people,” “anti-elitism,” and “ingroup favoritism”: “Populism (1) always refers to the people and justifies its actions by appealing to and identifying with the people; (2) it is rooted in anti-elite feelings; and (3) it considers the people as a monolithic group without internal differences except for some very specific categories who are subject to an exclusion strategy.” These three dimensions of populist discourse have found support among many researchers (Hawkins 2009; Moffitt and Tormey 2014; Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese 2017; de Vreese et al. 2018).

The “people” dimension of populist rhetoric highlights the sovereignty and the will of the people and claims to protect their interests against both outsiders and mainstream politicians (Canovan 1981; Taggart 2000; Mudde 2004; Jagers and Walgrave 2007; Cranmer 2011; Aalberg et al. 2017). It is at the very core of populism. Almost all populist politicians purport to speak for the common people and claim to express what the people really want as opposed to what the corrupt elites and mainstream politicians force upon them. When used against foreign aid, the “people” dimension of populist rhetoric often stresses the domestic costs of aid and the funds it diverts from the people along with the pretension that the people want to help citizens of their country rather than the poor and needy of the world. Nigel Evans, who sits on the UK's Commons International Development Committee, for example, said that “the taxpayer looks around towns and cities staring at potholes, police stations closed etc. and wonders why we've got money for foreign aid but not for essentials at home” (Dathan 2018). Nigel Farage, leader of the Brexit party, also targeted foreign aid when criticizing the British government's lack of support after a flood in 2014 for the people of Somerset: “The international aid budget is £11 billion [HK$140 billion] a year. All the government have offered so far is less than 1 percent of that in the form of £100 million … It feels to the people living [in Somerset] that we have a serious problem here and no one does anything, and no one cares” (South China Morning Post 2014).

Common people are typically juxtaposed with the evil elites in populist rhetoric. In claiming to speak for the people and protect their interests, populist politicians vilify and demonize elites and members of the establishment (Canovan 1981; Taggart 2000; Mudde 2004; Schultz et al. 2017). “Anti-elitism” claims that the elites—typically the liberal elites—pursue their own interests at the expense of the common people. They are corrupt. Not only are the elites disconnected from the people, but they are also trying to manipulate the people for their own interests (Jagers and Walgrave 2007). Of course, the notion of an elite is an amorphous one. Populist actors pick and choose their targets depending on the policy issue at stake. Broadly, however, the media, intellectuals, leaders of big corporations, and establishment politicians can all be conveniently included in the definition of the elite. When used to target foreign aid, populists employing anti-elite frames assert that the media and elites are manipulating the people to garner support for development aid. They also target elites in recipient countries and claim that foreign aid ends up benefiting the rich and corrupt leaders in poor countries, and thus is ineffective. Senator Rand Paul, for example, said that American foreign aid funds the autocrats and the rich in recipient countries (Washington 2012).

Jagers and Walgrave's third dimension of populist rhetoric is exclusion or what is also referred to as “ingroup favoritism.” Similar to the “people” frame, the in-group favoritism dimension points to out-groups vis-a-vis the “virtuous and homogeneous” in-group. As Mudde and Kaltwasser (2013) argue, this dimension of populism entails excluding out-groups both materially and politically for the well-being of the in-group. Material exclusion is about denying access to certain state resources to specific groups, such as immigrants, refugees, and more broadly to other non-native out-groups. Political exclusion is about keeping out-groups out of national political consideration and contestation. Simply put, this aspect of populist discourse, sometimes also called nativism, centers on “our own people first” (Cranmer 2011; Reungoat 2010). In the context of foreign aid, this frame typically manifests itself in the othering of the have-nots of the world and stressing a preference for taking care of in-group first. After all, the poor people in developing and less developed countries are “strangers.” Why should “our people” sacrifice for “them?” Denmark's Danish People's Party (DPP), for example, clearly stated “no more money for foreign aid at the expense of the Dutch” in its program (Olivié and Pérez 2020). This kind of thinking has also been at the center of anti-immigrant discourse adopted by Europe's populist politicians, such as Matteo Salvini of Italy.

We do not claim that these dimensions perfectly capture populism, and also acknowledge that they are related to one another.21 Our claim is simply that given what we know about populism, populist politicians tend to talk about foreign development aid along these three frames. This discussion on the three dimensions of anti-aid populist rhetoric leads to the following hypotheses:

H1a:Individuals exposed to the people frame of populist rhetoric will be less likely to support foreign development aid than those not exposed.

H1b:Individuals exposed to the anti-elite frame of populist rhetoric will be less likely to support foreign development aid than those not exposed.

H1c:Individuals exposed to the in-group favoritism frame of populist rhetoric will be less likely to support foreign development aid than those not exposed.

Getting the Message: Conditioning Effects of Beliefs about Populist Leaders

A number of studies have shown that populist messages are highly persuasive (Hawkins 2010; Rooduijn 2014; Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese 2017; Busby, Gubler and Hawkins 2019). Yet we also know there is a limit to the effect elite cues can have in affecting people's support for policies (Druckman 2001; Druckman and Nelson 2003; Boettcher and Cobb 2009; Kertzer and Zetizoff 2017). Scholars emphasizing the demand side of populism take issue with supply-side explanations that characterize populism largely as the product of populist strategies and rhetoric by politicians and political entrepreneurs (Pauwels 2011; Rooduijn, de Lange, and Van der Brug 2014; Aalberg et al. 2017). Demand-side arguments start with the premise that people are not blank slates, and that populism did not emerge out of the blue. Rather populist parties and movements tapped into existing—albeit possibly latent—populist ideas and beliefs (Hawkins, Riding and Mudde 2012; Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove 2014; Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck 2016; Bernhard and Hänggli 2018).

We argue that the persuasiveness of populist messages regarding foreign development aid is moderated by individuals’ prior beliefs about the perceived intentions of populist politicians. There is a well-established research agenda that emphasizes individual predispositions shaping views on foreign policy (Hurwitz and Peffley 1987; Hermann, Tetlock, and Visser 1991; Peffley and Hurwitz 1993; Kertzer et al. 2014; Rathbun et al. 2016; Bayram 2017b). We also know that predispositions condition the persuasiveness of elite cues (e.g., Guisinger and Saunders 2017; Kertzer and Zeitzoff 2017). Different authors have underscored the role that beliefs, attitudes, and values play in moderating both how members of the public (e.g., Gravelle et al. 2014; Gravelle, Reifler, and Scotto 2017) and political elites (e.g., Rathbun 2007; Thomson 2018) interpret foreign affairs and decide what policies to support. Nicholson and Segura sum it up quite succinctly: “Even if most people were exposed to backlash rhetoric, it does not mean that they believe it. Frames, regardless of their focus, do not automatically affect public opinion” (Nicholson and Segura 2012, 373).

Populist attitudes are notoriously difficult to measure, particularly in cross-national comparative studies (Castanho Silva et al. 2020). Recent electoral events in the UK and across the pond showcase that people can have rather different beliefs about the connotations of a leader being described as “populist.” At the risk of sounding unduly dramatic, one might paraphrase that “one person's scape-goating populist is another person's hero standing up for the little guy.” Academics are not the only ones grappling with how to conceptualize populism. The nationally representative UK Security Survey (2017) found that half of those surveyed admitted to not have given much thought to whether populists were mostly positive or mostly negative. Theoretically, this relative lack of crystallization might play a specific role in the way prior beliefs interact with different frames/cues.

Beliefs help organize and make sense of signals that might otherwise be confusing (George 1979; Verzberger 1990). They can play a pivotal role in processing political information (George 1969; Holsti 1977; Verzberger 1990), particularly “under one or more of the following conditions: novel situations; highly uncertain situations in which information may be scarce, contradictory, unreliable, or abundant; and stressful situations involving surprise and emotional strain” (Holsti 1977, 16–18). Importantly, beliefs shape sensitivity to cues (Verzberger 1990). Beliefs about human nature and individuals’ intentions can be particularly useful when it comes to foreign affairs, an area most people have limited factual knowledge about (Brewer and Steenbergen 2002; Kertzer and Zeitzoff 2017).

We argue that individuals will be more or less susceptible to populist rhetoric against foreign development aid depending on what they think of populist politicians. Individuals who believe populist leaders protect the interests of the common people will take populist arguments against providing foreign development aid seriously. In contrast, individuals who are distrustful of populist politicians will not be persuaded by populist arguments against aid. We make no claims regarding the origins of these beliefs here. We simply argue that many individuals exposed to populist messages have preexisting beliefs about populist leaders and general populist attitudes (Hawkins, Kaltwasser, and Andreadis 2018), and like many priors, these too will affect how a message is interpreted.

H2:Individuals who believe that populist politicians protect the interests of the people are more likely to be persuaded by populist rhetoric against foreign development aid than those who are skeptical of populist leaders.

Research Design, Method, and Data

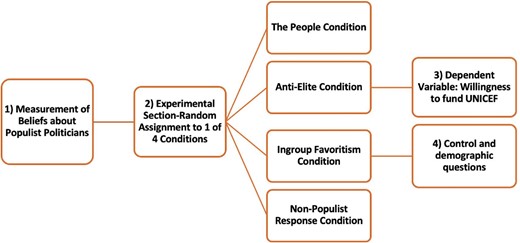

Our data come from nationally representative samples of 1,600 American and 1,200 British22 adults collected by YouGov in 2017–2018.23 We designed an original survey experiment to analyze the impact of the three dimensions of populist discourse on preferences toward multilateral development aid. Figure 1 captures the flow of the measurement process and the experimental design.

Before assigning participants to experimental conditions, we measured respondents’ prior beliefs about populist politicians by asking whether they see populist leaders as the kind of leaders who “stand up for the little guy” or “scapegoat out-groups” for America’s/Britain's problems. Existing measures of populist attitudes often directly allude to substantive preferences about elites or the common people (e.g., Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove 2014; Schulz et al. 2017). As our experimental scenarios include such content, measuring individuals’ populist attitudes more directly could have led to posttreatment bias. Hence, we created this measure to capture general priors about populist leaders.

We then informed respondents that they would read a hypothetical scenario that leaders of countries around the world have faced regarding multilateral development aid and handled in different ways. Our experiment had a between-groups design consisting of three treatment conditions that include rhetoric focused on people's will, anti-elitism, and in-group favoritism as well as a non-populist scenario calling for the creation of a committee (to serve as a quasi-control condition). All participants read a scenario in which UNICEF criticized the government and asked for more funding. The scenario read: The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) has publicly denounced the American/British government. Mr. Jean Morton, the head of regional operations made the following statement on television: “The United States/United Kingdom is not contributing enough funds to UNICEF, and what funds they provide are being earmarked for pet projects. We really need them to change course and increase America’s/Britain's commitment of funds, so we can deliver help to children in need across the globe.” Participants were then randomly assigned to one of four conditions, describing the response of the U.S. President/British Prime Minister.

The design of our experiment is guided by three analytical considerations. First, we opted for analyzing the effect of populist rhetoric on support for aid to UNICEF rather than support for bilateral aid because populists generally mistrust international organizations and multilateral aid, and UNICEF specifically has been a target of the Trump administration when it sought to eliminate funds for UN humanitarian and development programs (Goldberg 2019). It is easier for populist governments to back bilateral aid as it can be channeled in line with the national interests whereas multilateral aid is more problematic for populist leaders. Furthermore, among the international organizations with which publics are likely to be familiar, UNICEF is a relatively innocuous organization focused on helping vulnerable children. People's attitudes toward UNICEF are less likely to be politically and ideologically motivated than their attitudes toward the World Bank or United Nations Population Fund. Equally importantly, funding for UNICEF comes from both unearmarked and earmarked contributions provided by donor governments, and these funds are voluntary or discretionary contributions (UNICEF 2019). Voluntary contributions mean that financial contributions are not a legal obligation of membership, and thus donors control much funding to give to UNICEF and how these funds will be used.24 Of course, we recognize that support for UNICEF is only one indicator of support for foreign development aid. As we further explore in the conclusion, its main limitation is that it excludes support for bilateral development aid, specific aid projects such as combating terrorism or advancing gender equality, and support for aid to particular countries.

As an initial step in what we hope will be a long-term research agenda on populism and global development, we adopted two criteria for selecting our cases. First, we chose to focus on the largest donors (in nominal numbers) in the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) given their political importance for global development cooperation.25 The United States is the largest and the UK is the third largest donor of official development assistance.26 Second, among the top donors, only the United States and the UK have governments that have actively incorporated populist agendas and policies.27

Table 1 presents the experimental conditions. Each condition includes a response from the U.S. President/British Prime Minister. Three of these responses map onto a component of populist rhetoric we have discussed earlier; the non-populist response condition does not include a populist message. Note that our objective is not to distinguish the impact of general anti-aid rhetoric from populist anti-aid rhetoric. We are only interested in analyzing the effect of populist antidevelopment aid rhetoric. Therefore, our experimental design does not include a general anti-aid message condition.28

Experimental conditions

| People US N = 389 UK N = 321 | Anti-elite US N = 400 UK N = 260 | In-group favoritism US N = 408 UK N = 298 | Non-populist response US N = 384 UK N = 288 |

| The American (British) people, the men and women on the street, prefer to take care of American (British) children first. | The media and these humanitarian aid groups are exaggerating the situation to manipulate the American (British) people. | It is not our responsibility to help those people. Who should help these children are those countries that are more like them, not our people. | We will assemble a Congressional (Parliamentary) committee to examine the issue and see whether they recommend giving more funding to UNICEF. |

| People US N = 389 UK N = 321 | Anti-elite US N = 400 UK N = 260 | In-group favoritism US N = 408 UK N = 298 | Non-populist response US N = 384 UK N = 288 |

| The American (British) people, the men and women on the street, prefer to take care of American (British) children first. | The media and these humanitarian aid groups are exaggerating the situation to manipulate the American (British) people. | It is not our responsibility to help those people. Who should help these children are those countries that are more like them, not our people. | We will assemble a Congressional (Parliamentary) committee to examine the issue and see whether they recommend giving more funding to UNICEF. |

Experimental conditions

| People US N = 389 UK N = 321 | Anti-elite US N = 400 UK N = 260 | In-group favoritism US N = 408 UK N = 298 | Non-populist response US N = 384 UK N = 288 |

| The American (British) people, the men and women on the street, prefer to take care of American (British) children first. | The media and these humanitarian aid groups are exaggerating the situation to manipulate the American (British) people. | It is not our responsibility to help those people. Who should help these children are those countries that are more like them, not our people. | We will assemble a Congressional (Parliamentary) committee to examine the issue and see whether they recommend giving more funding to UNICEF. |

| People US N = 389 UK N = 321 | Anti-elite US N = 400 UK N = 260 | In-group favoritism US N = 408 UK N = 298 | Non-populist response US N = 384 UK N = 288 |

| The American (British) people, the men and women on the street, prefer to take care of American (British) children first. | The media and these humanitarian aid groups are exaggerating the situation to manipulate the American (British) people. | It is not our responsibility to help those people. Who should help these children are those countries that are more like them, not our people. | We will assemble a Congressional (Parliamentary) committee to examine the issue and see whether they recommend giving more funding to UNICEF. |

In the people condition, participants learned that the U.S. President/Prime Minister said that the American/British people prefer to help American/British children first. In the anti-elite condition, the President's/Prime Minister's response blamed elites for exaggerating the situation of global poverty and manipulating the American/British people. We operationalized the elite as the media and aid organizations. In the in-group favoritism condition, participants saw an exclusionary response by the President/Prime Minister. They were told that the President/Prime Minister said it was not America's/Britain's responsibility to help those out-groups and countries that are more like those out-groups should help them, not our people. In the no populist rhetoric condition, which serves as a quasi-control group, respondents were exposed to a politically routine response. We indicated that the President/Prime Minister called for assembling a congressional/parliamentary committee to evaluate UNICEF's request.

Our dependent variable measures participants’ willingness to contribute funds to UNICEF. We asked respondents whether they think the American/British government should provide additional funds to UNICEF. Responses were coded on a four-point scale marked by “Definitely give (coded 4),” “Probably give (coded 3),” “Probably not give (coded 2),” and “Definitely not give (coded 1).” Finally, our questionnaire included measures for generalized trust, party identification, and demographic questions such as income, education, age, gender.

Results

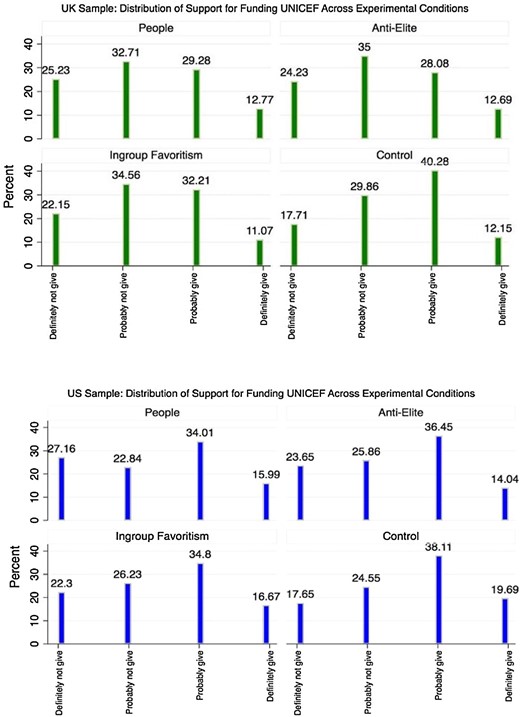

Respondents in our sample vary in their willingness to provide additional funds to UNICEF. In the British sample, about 12 percent express strong support for funding UNICEF while about 22 percent express strong opposition. About 33 percent say they will probably not support contributions to UNICEF and about 32 percent say they will probably support funding. In the American sample, about 16 percent of the respondents express strong support for funding UNICEF and 23 percent express strong opposition. About 36 percent of the American respondents chose the probably give funding and 25 percent probably not give funding options.

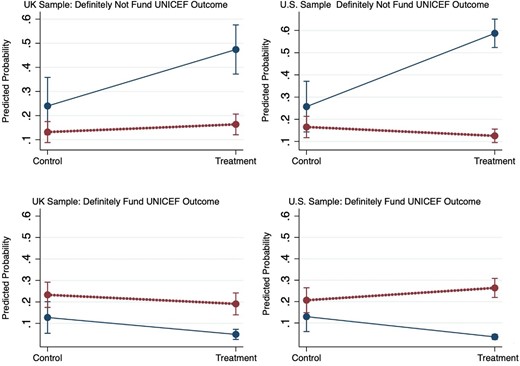

As Figure 2 shows, there is descriptive heterogeneity in support for funding UNICEF across experimental conditions in both the U.S. and UK samples.

Distribution of support for funding UNICEF across experimental conditions.

To test our hypotheses, we estimate a series of ordinal logistic regression models. This type of estimation is appropriate because our dependent variable is categorical and ordered but the scale is not marked such that one can meaningfully separate the categories by incremental numeric values (Long and Freese 2006).29

As set forth in our first set of hypotheses (H1a, b, and c), we expect that individuals exposed to the people, anti-elite, and in-group favoritism frames will be less likely to express support for giving funds to UNICEF than those who were in the condition calling for a Congressional/Parliamentary committee to be assembled (who were not exposed to any populist anti-aid rhetoric). We start with a baseline model that regresses support for funding UNICEF onto the experimental conditions to test these hypotheses.

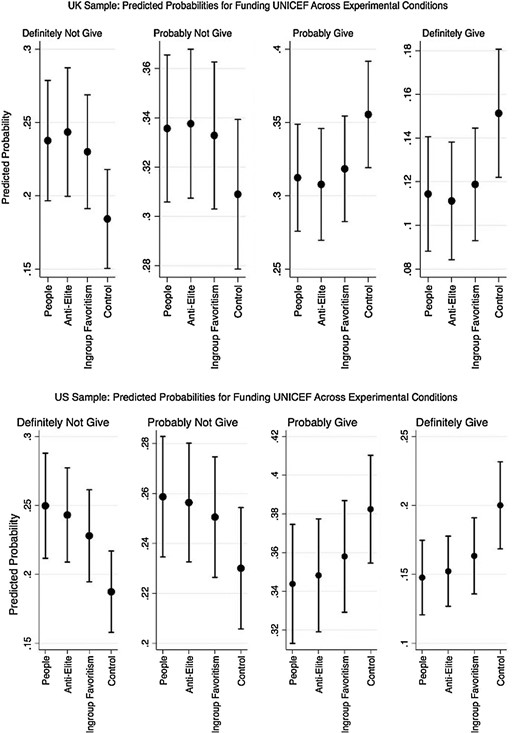

Overall, we find that populist anti-aid rhetoric stressing the will of the people, manipulation by corrupt elites, and the welfare of the in-group over out-groups has a statistically significant negative effect on both British and American respondents’ willingness to provide funds to UNICEF (Model 1).30 As can be seen in Figure 3, which presents the predicted probabilities, in the UK sample, those exposed to the treatments are about 6 percentage points more likely to say definitely not provide funding to UNICEF and about 4 percentage points less likely to say definitely give funding (compared with those in the control condition). The effect of the people and anti-elite dimensions of populist rhetoric are slightly larger than that of in-group favoritism. For example, the predicted probability of choosing definitely not give money to UNICEF is 2 percentage points lower in the in-group favoritism condition relative to the people and anti-elite conditions. In the U.S. sample, participants exposed to the people and anti-elite frames of anti-aid rhetoric are 7 percentage points and those exposed to the in-group favoritism frame are 5 percentage points more likely to choose definitely not fund UNICEF compared with the participants in the control condition. Similarly, participants who received one of the other populist experimental treatments are about 5 percentage points less likely to choose the definitely give funding option.

Predicted probabilities for funding UNICEF across experimental conditions.

Next, we add the variable measuring participants preexisting beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions (Model 2).31 This is an intermediate step to get at the main effects of the variables before we turn to our interaction models. We find that compared with those who think populist politicians stand up for the little guy, those who think they scapegoat out-groups are more likely to support financing UNICEF. Among British respondents who received the people treatment, those who think populists scapegoat others are 25 percentage points less likely to prefer to not provide additional funds to UNICEF and 12 percentage points more likely to say definitely give funds to UNICEF compared with those who think populist leaders stand up for the little guy. We observe a similar pattern in the anti-elite and in-group favoritism conditions.

We also find that the effect of anti-aid populist discourse is smaller for respondents who are uncertain about the intentions of populist politicians. For instance, Britons who think that populists “neither scapegoat others nor stand up for the people” or provided “I don't know” answers are about 13 percentage points less likely to say definitely not give funds to UNICEF compared with those who think populists stand up for the little guy (across all populist experimental conditions).

Similarly, among American respondents exposed to populist treatments, those who believed that populist leaders stand up for the little guy are 18 percentage points less likely to choose the definitely provide additional funding option to UNICEF than those who think populist leaders scapegoat out-groups. If we look at the anti-elite and in-group favoritism treatments, this difference in likelihood is about 15 percentage points. In the people condition, the predicted probability of choosing to definitely not provide additional funding to UNICEF is 53 percentage points for those who think populist leaders stand up for the little guy but drops to 13 percentage points for those who think populist leaders scapegoat out-groups (compared with 0.26 and 0.17 for those who provided “neither” and “don't know” answers, respectively).

Having discussed the main effects in both the British and American samples, we now turn to our predictions regarding the interaction between populist rhetoric and individuals’ prior beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions. Our second main hypothesis (H2) predicts that individuals who believe populist politicians protect the interests of the people are more likely to be persuaded by populist rhetoric against foreign aid than those who are skeptical of populist leaders. To test whether prior beliefs about populist politicians influence the effect of exposure to populist rhetoric on support for funding UNICEF, we include interaction terms between prior beliefs and experimental conditions. The crux of this interaction effect can be found in a simplified model (Model 3ʹ in Table 2) that regresses support for funding UNICEF onto a binary treatment variable (coded “1” if respondents received any of the populist messages and “0” if they were assigned to the control group and thus did not receive any populist communication), a binary prior beliefs variable that excludes the neither and don't know answers (coded “1” if respondents think populist leaders scapegoat out-groups and “0” if they believe populist leader stand up for the little guy), and an interaction term between the treatment and prior beliefs variables. We show this streamlined analysis in order not to present too many group comparisons here. In the Online Appendix, we use all the categories of the experimental conditions and the prior beliefs variable and present all the subgroup comparison graphs, while outlining the differences among Britons and Americans.32

Prior beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions moderate the impact of populist rhetoric on willingness to fund UNICEF

| . | Model UK 3ʹ . | Model US 3ʹ . |

|---|---|---|

| Populist rhetoric treatment | −1.000** (0.363) | −1.4138*** (0.328) |

| Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions (scapegoat out-groups = 1, stand up for the little guy = 0) | 0.727** (0.353) | 0.558* (0.341) |

| Populism treatment × Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions | 0.707* (0.406) | 1.73491*** (0.348) |

| Cutpoint 1 | −1.123 (0.332) | −1.060 (0.304) |

| Cutpoint 2 | 0.225 (0.318) | 0.00787 (0.300) |

| Cutpoint 3 | 1.935 (0.330) | 1.905 (0.314) |

| Wald χ² | 56.12*** | 166.12*** |

| Log likelihood | −737.59609 | −840.98928 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0436 | 0.0975 |

| N | 566 | 691 |

| . | Model UK 3ʹ . | Model US 3ʹ . |

|---|---|---|

| Populist rhetoric treatment | −1.000** (0.363) | −1.4138*** (0.328) |

| Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions (scapegoat out-groups = 1, stand up for the little guy = 0) | 0.727** (0.353) | 0.558* (0.341) |

| Populism treatment × Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions | 0.707* (0.406) | 1.73491*** (0.348) |

| Cutpoint 1 | −1.123 (0.332) | −1.060 (0.304) |

| Cutpoint 2 | 0.225 (0.318) | 0.00787 (0.300) |

| Cutpoint 3 | 1.935 (0.330) | 1.905 (0.314) |

| Wald χ² | 56.12*** | 166.12*** |

| Log likelihood | −737.59609 | −840.98928 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0436 | 0.0975 |

| N | 566 | 691 |

***p ≤ .001, **p ≤ .05, *p ≤ .10.

Notes: Reported values are ordinal logistic regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable measures participants’ willingness to contribute funds to UNICEF. It ranges from 1 to 4, where 1 is coded as “definitely not give funds” and 4 is coded as “definite give funds.” The “control” group is the reference category for the variable (no populist rhetoric treatment) and “populist politicians stand up for the little guy” is the reference category for the variable (prior beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions).

Prior beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions moderate the impact of populist rhetoric on willingness to fund UNICEF

| . | Model UK 3ʹ . | Model US 3ʹ . |

|---|---|---|

| Populist rhetoric treatment | −1.000** (0.363) | −1.4138*** (0.328) |

| Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions (scapegoat out-groups = 1, stand up for the little guy = 0) | 0.727** (0.353) | 0.558* (0.341) |

| Populism treatment × Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions | 0.707* (0.406) | 1.73491*** (0.348) |

| Cutpoint 1 | −1.123 (0.332) | −1.060 (0.304) |

| Cutpoint 2 | 0.225 (0.318) | 0.00787 (0.300) |

| Cutpoint 3 | 1.935 (0.330) | 1.905 (0.314) |

| Wald χ² | 56.12*** | 166.12*** |

| Log likelihood | −737.59609 | −840.98928 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0436 | 0.0975 |

| N | 566 | 691 |

| . | Model UK 3ʹ . | Model US 3ʹ . |

|---|---|---|

| Populist rhetoric treatment | −1.000** (0.363) | −1.4138*** (0.328) |

| Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions (scapegoat out-groups = 1, stand up for the little guy = 0) | 0.727** (0.353) | 0.558* (0.341) |

| Populism treatment × Prior beliefs about populist leaders’ intentions | 0.707* (0.406) | 1.73491*** (0.348) |

| Cutpoint 1 | −1.123 (0.332) | −1.060 (0.304) |

| Cutpoint 2 | 0.225 (0.318) | 0.00787 (0.300) |

| Cutpoint 3 | 1.935 (0.330) | 1.905 (0.314) |

| Wald χ² | 56.12*** | 166.12*** |

| Log likelihood | −737.59609 | −840.98928 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0436 | 0.0975 |

| N | 566 | 691 |

***p ≤ .001, **p ≤ .05, *p ≤ .10.

Notes: Reported values are ordinal logistic regression coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable measures participants’ willingness to contribute funds to UNICEF. It ranges from 1 to 4, where 1 is coded as “definitely not give funds” and 4 is coded as “definite give funds.” The “control” group is the reference category for the variable (no populist rhetoric treatment) and “populist politicians stand up for the little guy” is the reference category for the variable (prior beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions).

In support of our hypothesis, we find that individuals’ prior beliefs about populist politicians’ intentions do matter. These beliefs affect how susceptible respondents are to populist rhetoric. Table 2 reports the results of the simplified model (Model 3ʹ), and figure 4 reports the predicted probabilities obtained from this model for the definitely give and definitely not give funding to UNICEF outcomes.

Predicted probabilities for funding UNICEF by experimental conditions and beliefs about populist leaders (Model 3ʹ). Note: The solid line represents populist stand up for the little guy, dotted line represents populist scapegoat outgroups.

As can be seen, in both the UK and US samples, the interaction term is positive and statistically significant. A positive interaction term in our estimation means that people who trust populist leaders are persuaded more by populist rhetoric against aid than those who are suspicious of populists. Put differently, populist rhetoric against aid has a larger impact on the willingness to fund UNICEF when people think populist leaders represent the will of the people than when they think populist leaders scapegoat out-groups. Looking at the predicted probabilities illustrates this result. In the UK sample, among the participants exposed to anti-aid populist rhetoric, those who believe that populist leaders scapegoat out-groups are about 30 percentage points less likely to choose the “definitely not give funding” outcome and 15 percentage points more likely to prefer the “definitely give funding” outcome relative to those who believe populist leaders stand up for the little guy. Similarly, in the U.S. sample, among the respondents who were exposed to anti-aid populist rhetoric, those who believe that populist leaders scapegoat out-groups are 23 percentage points more likely to prefer to “definitely give funding” to UNICEF than those who believe populist leaders stand up for the little guy. And participants who think that populist leaders scapegoat out-groups are 46 percentage points less likely to prefer to “definitely not give funding” to UNICEF than those who believe populist leaders stand up for the little guy. These findings decidedly indicate that populist rhetoric works differently among different groups of people depending on what they think of populist politicians.

Finally, we present robustness checks. Bayram (2017a) has found that individuals who are generally more trusting of other human beings are more supportive of foreign development aid. Milner and Tingley (2010, 2011) have demonstrated that individuals who are more educated and higher income tend to be more supportive of foreign aid. Scholars have also shown the importance of partisanship for public attitudes toward aid (Thérien and Noël 2000; Milner and Tingley 2010). Accordingly, we control for respondents’ social trust, income, education, party identification as well as gender, and age as demographic factors.33 In terms of social trust and demographic controls, our results largely map onto previous research. We observe however, some cross-national differences. In the UK, individuals who are more educated and on higher incomes, younger, identify as female, are more trusting of human beings, and support the Liberal Democratic Party, the SNP, or the Green Party are more supportive of funding UNICEF. In the United States, we do not observe any effects for income and education, but we do find that younger people, individuals who identify as female and have high social trust, and Democrats are more supportive of funding UNICEF. Crucially, in both samples, the inclusion of control variables does not change our results for populist rhetoric and its interaction with prior populist attitudes on financing UNICEF. Across both the British and American samples, our findings indicate that the effect of populist anti-development rhetoric is moderated by individuals’ preexisting beliefs about populist politicians.

Conclusion

While research on populism is not new, rising support for populist parties and leaders across Europe and in the United States in the last decade has led to renewed scholarly interest in populism. Since the end of the Cold War, reducing poverty in the world has been an important goal of developed countries. Despite the ebb and flow of government spending on foreign development aid, the targets and priorities set by the global development goals have largely been embraced by donor countries. Yet the tide seems to have turned. Populist parties and politicians continue to portray overseas aid spending as the enemy of prosperity “at home.” In this paper, we have investigated how populist rhetoric against foreign aid affects donor public attitudes using data from survey experiments conducted with nationally representative samples of Britons and Americans.

We have shown that populist politicians’ hostility toward aid does indeed spill over to the public but this spillover has limits. Even though exposure to populist anti-aid rhetoric couched as protecting the people, countering elite manipulation, and putting the in-group first decreases support for financing UNICEF, these effects are moderated by individuals’ prior beliefs about populist politicians. Dispositional populists, namely, those who think populists stand up for the average person are easily persuaded by populist messages. Yet those who are distrustful of populist politicians are significantly less susceptible to such messages. Our research constitutes a first step in providing cross-national evidence on the relationship between populist rhetoric and foreign aid attitudes. In the cases of the U.S. and the UK, our results are consistent with analyses that emphasize the variation in individual receptivity to populist messages (e.g., Bos, Van der Brug, and de Vreese 2013; Hameleers, Bos, and de Vreese 2017; Hameleers and Schmuck 2017; Hawkins, Kaltwasser, and Andreadis 2018).

Our findings suggest that supply-side explanations for increased public support for populist parties and politicians should pay more attention to the demand side of populism. The power of populist rhetoric did not emerge out of thin air. Given the importance of prior beliefs about populist leaders, there might be ways to push back against ultranationalist and exclusionary populist tides in the context of international development. While dispositional populists might be keen to oppose aid when exposed to populist anti-aid rhetoric, our research shows that there are categories of non-populists who will not easily buy into populist anti-aid rhetoric. These categories not only include those who explicitly view populist leaders as scapegoating some groups for national problems—it also includes those who do not have crystalized views on populist leaders. This has two main policy implications. First and foremost, it means that international aid institutions and non-populist politicians should not be unduly worried about the impact of populism on global development cooperation. Populists are not converting pro-aid individuals with their rhetoric; they are preaching to those predisposed to be converted.

Second, the identification of these groups means that public engagement and development communication efforts can be targeted accordingly. The emphasis could be moved toward supporting foreign aid by following “best practices”34 in development communication such as transparency, articulating a clear vision, and leveraging local partnerships. And while it may be easier to instill support for aid in people who are already skeptical of populists, those who are uncertain about the goals of populists should not be ignored as a group. In showing the limits of populist rhetoric as a function of preexisting beliefs, our findings highlight the importance of development communication for aid policy.

The present study contributes to a deeper understanding populism and foreign policy, yet there are a number of limitations that should be noted. First, we have limited our research to foreign development aid. It is possible that populist messages operate differently in policy domains such as national security. It is also conceivable that voters respond to populist appeals differently in the context of bilateral aid or international institutions other than UNICEF. Future studies could investigate whether our findings generalize to different types of aid as well as explore how the characteristics of different multilateral aid organizations, such as UNFPA, World Food Program, or the Red Cross, interact with populist politics. Scholars could also go beyond the largest DAC donors and examine how populism affects those nations that both give and receive development aid as well as smaller donors.

Because our experimental treatments have exposed participants to substantive populist content, we have not measured general populist attitudes with existing indices (e.g., Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove 2014) to avoid posttreatment bias. Future research could provide additional tests of our findings by examining how populist attitudes, rather than beliefs about populist leaders, moderate the effect of anti-aid populist frames on individual preferences. Similarly, focusing on the effect of different populist anti-development aid frames, we have not included a non-populist anti-aid aid message condition in our design, for example one that opposes aid claiming that it gets wasted on corrupt governments. We are cognizant of the difficulty of separating populist opposition to aid from non-populist opposition, but still encourage future studies to take on this challenge. Finally, we have focused on the content of populist communication and not examined the variations in the “form” of these communications. Future research could explore how different forms of populist communication (such as messages on billboards, campaign posters, or tweets) differ from non-populist communication and how they influence public opinion on foreign policy issues.

A. Burcu Bayram is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Arkansas. Her research applies insights from political psychology and behavioral economics to the study of international cooperation to understand public and elite preferences.

Catarina P. Thomson is Senior Lecturer in Security and Strategic Studies in the Politics Department at the University of Exeter, UK. Her work incorporates political psychology and domestic factors to understand the strategic behavior of actors in times of international conflict. She is unreasonably proud to be the latest winner of her campus’ “Whose Lecture is it Anyway” Comedy Improv trophy.

Notes

Authors’ note: A. Burcu Bayram acknowledges partial support by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation. Catarina P. Thomson acknowledges support from the UK Economic and Social Research Council grant ES/L010879/1 and the University of Exeter's SSIS Strategic Discretionary Research Fund.

We are grateful for comments provided by Sebastian Schneider, Thomas Scotto, Kate Davies, Erik Petersen, Nehemia Geva, and participants at the Political Behavior and Political Institutions workshop at Texas A&M University. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers, the editors, and participants at the Foreign Aid and Public Opinion conference sponsored by the University of Geneva and by the Gates Foundation for their valuable feedback. Above all else, we are grateful for random encounters at conferences, without which this paper would not have been possible.

Footnotes

The data used in this paper can be found at ISQ Dataverse. In this paper, our focus is only on foreign development aid. Of course, there are other types of foreign aid, such as military and humanitarian aid and postcrisis ad hoc aid. At times, we refer simply to “aid” for stylistic reasons.

Comparing views on these matters is not our focus here. However, other UK Security Survey items can help paint a descriptive picture about the relationship between some of these items. One item measured whether respondents considered “large number of economic migrants coming into the UK” as a critical threat. Attitudes toward foreign aid were gauged by asking whether “the UK should spend significantly more money on foreign aid.” The correlation between these items is −0.23. Forty three percent of those in the highest social grade agreed with the idea that the UK should spend significantly more on foreign aid. This figure is about half among respondents in the lower grades.

BNP manifesto available at http://bnp.org.

AfD manifesto available at https://cdn.afd.tools/wp-content/uploads/sites/111/2017/04/2017-04-12_afd-grundsatzprogramm-englisch_web.pdf.

Conservative Manifesto entitled Get Brexit Done available at https://assets-global.website-files.com/5da42e2cae7ebd3f8bde353c/5dda924905da587992a064ba_Conservative%202019%20Manifesto.pdf.

UKIP manifesto available at https://www.ukip.org.

Episode 8 of series 52 of “Have I Got News for You” BBC show.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-49833804, Accessed March 6, 2021.

See, for example, Flinders (2020) on what makes Johnson a populist and how he created a unique form of British populism.

Former Conservative MP Nick Boles went further and claimed that the Conservative party was finished due to the hard right taking over under Johnson (Maidment 2019).

Johnson ended up entering an agreement with Nigel Farage's Brexit Party under which they did not field candidates in all constituencies (Grice 2019).

Ken Clarke, the Former Chancellor and Conservative MP since 1970, was one of those expelled and stated that “[This is a] cabinet which is the most right-wing cabinet any Conservative party has ever produced. They're not in control of events. The PM comes and talks total rubbish to us and is planning to hold a quick election and get out, blaming parliament and Europe for the shambles” (Vaughan 2019).

Perhaps particularly credible campaign rhetoric given Johnson's previous decision to suspend parliament for five weeks (later declared unlawful by the Supreme Court) https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-49810261.

Our use of demand and supply sides of populism is in line with the populism literature in political science and is not meant to reflect how demand and supply operate from an economic perspective.

For reviews on foreign aid, also see Wright and Winters (2010) or Qian (2015).

Scholars are increasingly recognizing the importance of studying populist rhetoric and communication as well as seeking to identify the unique characteristics of populist rhetoric such as accusatory and emotional language and the separation of the “good people” from the dangerous outsiders or elites (e.g., de Vreese et al. 2018; Mazzoleni, and Bracciale 2018; Gerstlé and Nai 2019; Reinemann et al. 2019; Rooduijn 2019; Sagarzazu and Thies 2019; Levinger 2017).

In particular, the rhetoric associated between the first and third frames described here is quite similar. Furthermore, it can be argued that all three of these dimensions or a mix of them need to be present for a message to count as populist. Given the theoretical distinction made between them in the literature we introduce each dimension separately.

For sample characteristics, see the Online Appendix. The British experiment was conducted as part of the UK Security Survey.

For YouGov sampling process, see the Online Appendix.

UNICEF technically has the authority to allocate resources through different program priorities. However, because of the voluntary nature of the contributions, donor member countries are not obligated to accept these multilateral decisions as binding (Graham 2015; Bayram and Graham 2017). The nature of funding rules at UNICEF makes it a sensible case to study foreign development aid because donor control can be channeled for political advantage with domestic constituencies by populist politicians or used to withdraw funding all together.

Germany is the second largest donor, but the AfD has not been part of the governing coalition. Admittedly, our case selection criteria exclude smaller European donors such as Poland and non-DAC members such as Turkey and India who both receive and give aid.

We cannot rule out the possibility that participants might be responding to reluctance to fund UNICEF embedded in populist frames rather than the populist frames themselves. However, participants understood and reacted to the populist frames presented in the experimental treatments. In a post-experimental check, we asked participants how they would characterize the President's/PM's response to the request from UNICEF. A chi-square test shows that participants assigned to the treatment conditions were more inclined to describe the President's/PM's response as populist than those assigned to the control condition [U.S. sample: X2 (3, N = 1581) = 15.11, p = .002 and UK sample: X2 (3, N = 1167) = 37.26, p = .0020].

Additional robustness checks in the Online Appendix using OLS regression yield similar results.

See Model 1 in Table A1 in the Online Appendix for full results. US sample: Kruskal–Wallis test (χ² = 9.894, p = .02). UK sample: Kruskal–Wallis test (χ² = 7.608, p = .05). The Kruskal–Wallis test is a nonparametric test used to compare two or more groups and determine whether the medians of these groups are statistically different when the assumptions of analysis of variance (ANOVA) are not met. In the case of our dependent variable, the assumption of normal distribution is met in the US sample but not in the UK sample. In addition, we do not consider our dependent variable to be a continuous variable. However, the results from ANOVA are comparable and show significant differences across experimental treatment groups (US sample: [F(3, 1577) = 3.3, p = .01] and UK sample: [F(3, 1163) = 2.20, p = .06].

See Model 2 in Table A1 in the Online Appendix for full results.

Model 3 in Table A1 in the Online Appendix.

Also see Paxton and Knack (2012) for relevant covariates considered in robustness checks. See the Online Appendix for full results. We do not find an interaction between prior foreign aid attitudes and experimental treatment conditions.

See, for example, OECD Development Communication Network reports on such practices. Available at http://www.oecd.org/dev/pgd/devcom-publications.htm.