-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paul Chaney, Ian Rees Jones, Ralph Fevre, Exploring the Substantive Representation of Non-Humans in UK Parliamentary Business: A Legislative Functions Perspective of Animal Welfare Petitions, 2010–2019, Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 75, Issue 4, October 2022, Pages 813–842, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsab036

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This study is concerned with the substantive representation of non-human species in parliamentary business. It applies Leston-Bandeira’s legislative functions perspective (LFP) to a data set of 2500 public petitions on animal welfare, submitted over three terms of the UK parliament. The wider significance of this work lies in: (i) underlining the utility of the LFP to petitions analysis; (ii) showing that, while few directly secure policy change, e-petitions perform valuable legislative functions including campaigning, scrutiny and policy-influencing roles, foremost of which is linkage and fostering citizen engagement in parliamentary business. And (iii) Showing how, over the past decade, public petitions have significantly contributed to the increasing salience of animal welfare in UK politics.

1. Introduction

This study is concerned with the substantive representation of non-human species in parliamentary business with reference to public petitions on animal welfare submitted over three terms of the UK parliament: 2010–2015, 2015–2017 and 2017–2019. The overarching research aim is to examine what the Westminster petitions data tell us about the nature of civil society claims on animal welfare. This is an appropriate locus of enquiry because, as a seminal series of studies attests, from an international perspective, public petitions have become an increasingly important mechanism whereby the public can submit their policy demands to parliamentarians (Jungherr and Jurgens, 2010; Bochel 2013; Carman, 2014; Leston-Bandeira 2019). Despite this, political science has tended to give limited attention to the co-existence of human and non-human species. As McCulloch (2019, p. 8) cogently notes, ‘there are few authors that have written about animal protection in a political science context. This is unfortunate because developments in animal welfare science require changes at the political level for meaningful reform’.

In part, such oversight stems from traditional thinking whereby ‘animals [have] figured in the modern project principally as resource for human progress’ (Macnaghten, 2001, p. 4). Yet, over recent decades, this subordination of animals has been seriously questioned, as reflected in the significant increase in public concern in the UK over animal rights and welfare (Ipsos Mori, 2018). In turn, this has been driven by a variety of factors including widespread publicity and prosecution of animal cruelty cases (Hughes et al., 2011); and, building on seminal work by the Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC, 1979; Webster, 1994),1 ‘a surge of interest in animal sentience [… and] understanding of how animals feel’ (Duncan, 2006, p. 8; see also Nurse, 2016). This has potentially significant implications for substantive representation in legislative settings. In other words, advancing the needs and wants of specified groups or interests in policy and law making (Pitkin, 1967). As Jones (2015, p. 467) cogently explains, ‘those committed to social justice—to minimizing violence, exploitation, domination, objectification, and oppression—are equally obligated to consider the interests of all sentient beings, not only those of human beings’.

While the substantive representation of non-human species in parliamentary settings has largely been overlooked, an earlier manifesto study provided evidence that over recent years the issue has gained greater salience in UK politics. Almost a decade ago it concluded that, ‘the status of animal welfare as a policy issue remains ‘fragile’; while no longer excluded from party programmes, significant further work remains before it is fully mainstreamed into the formative phase of policy-making in UK electoral politics’ (Chaney, 2014, p. 907). More recent analysis points to sharp increase in the level of attention to animal welfare in parties’ election manifestos, such that it is now a mainstream, party-politicised issue in many party programmes (Chaney et al., 2020). However, as partisan theory explains, although political parties’ manifestos act as a key vector to advance public concerns into parliamentary business (Vogeler, 2019), they are not the only agenda-setting mechanism shaping substantive representation in legislative settings.

Following some initial innovations from the Blair/Brown governments (1997–2010), in 2011, the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government (2010–2015) introduced an e-petitions system at Westminster. As Bochel (2013, p. 798) presciently noted at the time, ‘as a tool for participation they [public petitions] have the potential to act as a significant input to representative forms of democracy by providing a mechanism to enable the public to express their views to those in elected representative institutions’. This has proven to be correct. As the Hansard Society (2017, p. 5) concluded, ‘One positive development is the e-petitions system … more than one-in-five people had signed an e-petition in the last year. Since 2015 there have been more than 31 million signatures … This is a significant number of individuals getting involved with parliamentary processes’.

However, as the following discussion reveals, we need to assess the importance of public petitions in a more sophisticated manner than simply the number of signatories. The reality is petitions are not always effective in securing policy change (and arguably rarely are), in which case, the value of petitions lies in making people feel that they are participating and drawing attention to an issue whereas, in policy terms at least, they may be achieving little. By fostering civil society engagement in parliamentary business, e-petitions can be seen as the latest chapter in the pursuit of participatory democracy. This concept has its roots in the work of classic liberal theorists such as J.S. Mill (2016/1859) and J.J. Rousseau (1974 [1762]), as well as more recent advocates such as Pateman (1970), who underlines the educative function of participation as part of a process by which people learn citizenship—and in doing so, strengthen democracy. As Barber (1984, p. 265) puts it ‘[t]he taste for participation is whetted by participation: democracy breeds democracy’. Along with the literature on participatory democracy, Leston-Bandeira’s (2019) seminal legislative functions perspective (LFP) allows us to better understand the significance of Westminster’s e-petition system. By applying the LFP to the data set of animal welfare petitions, we can appreciate the multiplicity of roles performed by the petitions system. Thus, this exploratory study provides insight into contemporary political thinking on the co-existence of humans and non-humans, evolving notions of sentience (see below), and how these are related to evolving structures and processes of parliamentary democracy.

As the following discussion reveals, the present analysis validates the LFP and, countering fears expressed in the early-2000s about a democratic deficit or ‘disconnect’ between parliament and the people; it shows how the Westminster petitions system is providing key opportunities for new levels and modes of political engagement (‘linkage’) for citizens and organised civil society alike. In the latter regard, the following analysis shows that NGOs (Non Governmental Organisations) draft the majority of mass support petitions (100,000+ signatures). Subsequently, they use their campaigning techniques—e-mail lists, social media and the like, to mobilise support and promote the petitions among their supporters. This is an important new dimension to NGOs’ action repertoires; one that did not exist prior to 2010.

The remainder of this article is structured thus: a discussion of the research context is followed by an outline of the study methodology. The research questions are then discussed in turn: 1. What issues do petitioners want parliamentarians to address? 2(a). How does the number and nature of animal welfare petitions change over the course of the three parliaments? 2(b). How does the level of attention to animal welfare compare to other policy issues? 3. How do petitioners frame their claims? 4(a). Which issues gain the most support? 4(b). How does government respond to the most popular petitions? 5(a). What are the main reasons for petitions being rejected? And 5(b). What do the data tell us about the (multi-level) ‘governance literacy’ of petitioners? 6. What do we know about whether animal welfare petitions are submitted by NGOs as opposed to individuals? And as noted, 7. We then apply the data set to legislative functions framework to identify whether it supports the multiplicity of roles performed by petitions predicted by the LFP. The conclusion summarises the core findings and discusses their significance.

2. Research context

Over recent decades, animal welfare has become a prominent issue in many Western democracies (Sunstein and Nussbaum, 2006; Lundmark et al., 2014). It is a contested concept with varying definitions. A full discussion is outwith the present purposes. As Carenzi and Verga (2009, p. 22) observe, it is a ‘multi-faceted issue which implies important scientific, ethical, economic and political dimensions’. For the present purposes, it refers to the avoidance of the negative feelings and experiences related to the ‘Five Freedoms’ (freedom from: thirst, hunger, and malnutrition; discomfort and exposure; pain, injury, and disease; fear and distress; and freedom to express normal behaviour—see McCulloch, 2013; Webster 1994; FAWC, 1979). In addition, it incorporates more sophisticated conceptualisations concerned with sentience, the generation of positive and subjective animal experiences, and improving human–animal relations (see Mellor, 2016).

As an umbrella term, animal welfare spans a series of sub-fields including the following: farm animal cruelty cases (Weary, 2018); animal testing of drugs, cosmetics and other products (Monamy, 2017); hunting and animal involvement in ‘sports’; habitat loss and climate change (Butterworth, 2017); debates around human consumption of meat (Rachels, 2012); intensive livestock and poultry farming techniques (Cornish et al., 2016); and the use of fur and animal products in garments and other products (Makarem and Jae, 2016).

Recent public attitudes data reveal that in the UK, ‘animal welfare is becoming a bigger consideration for some members of the public … while interest in … improve[ing] the welfare of animals in research is high and has risen. Close to six-in-ten are interested in both aspects’ (Ipsos Mori, 2018, p. 7). It should also be noted that public concern is likely to increase over future years because, compared with older people, current data show that ‘younger people appear particularly concerned about animal welfare’ (Ipsos Mori, 2018, p. 8).

Increasing public concern over the issue raises questions about the best way for the public to press their animal welfare policy claims on parliamentarians. This resonates with successive Westminster parliamentary inquiries on the need to address a growing participation gap within society. For example, at the end of the 2005 Parliament, the Select Committee on the Reform of the House of Commons (the Wright Committee) highlighted the need to, ‘make the Commons matter more, increase its vitality and rebalance its relationship with the executive, and to give the public a greater voice in parliamentary proceedings’ (HoC, 2005, p. 7). Subsequently, in 2009, the House of Commons Reform Committee recommended that, ‘the only more or less direct means for those outside the House to initiate proceedings is through presentation of a petition, a practice of great antiquity’ (HoC Reform Committee, 2009, para 235). The Tory-Liberal Democrat coalition Government’s e-petitions website was launched on 4 August 2011. The intention was that petitions securing 100,000 signatures would be eligible for debate in the HoC. Yet, just two years later, the HoC Political and Constitutional Reform Committee (2013, p. 3) concluded that, ‘The present procedure for setting the agenda for most of the House’s business—that which is not decided by the Backbench Business Committee—is inadequate’ (HoC Political and Constitutional Reform Committee, 2013, p. 3). Following a report by the HoC Procedure Committee (2014), the House debated proposals for a collaborative (hybrid executive-legislative branch) system of e-petitions. Subsequently, a joint e-petitions website overseen by a new Petitions Committee went live on 20 July 2015 (for a discussion see Kelly and Priddy, 2015).

According to the rules on petitions,2 only British citizens and UK residents can create a petition via the UK Government and Parliament site. If it complies with the standards for petitions, other British citizens and UK residents can then sign it. The Parliamentary Petitions Committee reviews all published petitions and has the power to press for action from government or Parliament. Petitions securing 10,000+ signatures will get a response from the government. Those attaining 100,000+ signatures will also be considered for a debate in Parliament. When the Parliamentary Petitions Committee and/or Members of Parliament feel they need more information on an issue, the Committee can undertake an evidence gathering role (it oversaw two inquiries in the 2015–2017 Parliament).

3. Methodology

An electronic database of all animal welfare petitions (2010–2019) was created by downloading petitions from the UK Parliament website. Animal welfare petitions were identified from all parliamentary petitions using keyword searches (inter alia, animal, wildlife, greyhound, hare, pets, badger, hunting, fox, vivisection, sentience, etc.). Analysis of the different issues or topics covered in the animal welfare petitions was operationalised using content analysis (Neuendorf, 2016). This measures the frequency of key terms or signifiers, thereby giving an indication of their relative importance compared to other issues in the data set. All petitions were logged into a spreadsheet allowing descriptive statistical analysis. The coding frame of different animal welfare issues in the data set was determined using deductive coding schemata. Finfgeld-Connett (2014, p. 342) explains the process: ‘using a deductive approach, the reviewer begins data analysis with a coding template in mind, and data are organised according to an existing, though alterable, structure. Alterability is important since one aim of qualitative systematic reviews is to test, adapt, expand, and in general, improve upon the relevance and validity of existing frameworks’. The initial codes were derived from a close reading of the relevant literature (see Reference list, e.g. FAWC, 1979; Duncan, 2006; Carenzi and Verga, 2009; Jones, 2015). Additional codes such as ‘diplomacy’ were identified as the coding process proceeded (‘diplomacy’ refers to petitions calling on government to act on animal welfare issues overseas, such as ‘Eliminate Elephant poaching now’3 and ‘Urge the end of the Yulin Dog Meat Festival’).4 Because these are outside the UK government’s jurisdiction, diplomacy is the principal way government can respond to such petitions.

In total, the dataset of animal welfare petitions was coded four times. The first round of coding distinguished the different animal welfare issues covered by the petitions. To avoid double counting and issues of overlap, it should be noted that the topic code ‘Generic—stricter regulation’ refers to petitions calling for stronger regulation of animal welfare in general (i.e. it is a discrete heading and does not relate to the other coding categories—such as wildlife, exports, circuses in Table 1). Examples of the general stricter regulation petitions include the following: ‘Stop MPs banning the RSPCA [Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals] from prosecuting those who are cruel to animals’; ‘Don't take prosecution powers away from RSPCA, give them more powers’; ‘Implement a statutory body to deal with animal welfare prosecutions’; ‘Increase maximum sentencing for animal cruelty from 6 months’; ‘Introduce a register of people who are convicted of animal cruelty’; and ‘Review the sentencing guidelines for offences of deliberate animal cruelty’.

Percentage of all animal welfare petitions by topic in successive Westminster Parliaments 2010–2019 (N = 2,453)a

| Topic . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter general animal welfare regulation | 21.5 | 26.0 | 20.5 | 21.7 |

| Wildlife | 9.0 | 10.6 | 20.9 | 15.2 |

| Pets | 22.5 | 20.2 | 7.5 | 14.7 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 14.1 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 8.3 |

| Slaughter | 8.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 7.0 |

| Fireworks | 2.7 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 6.1 |

| Sentience | 0.1 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 4.7 |

| Testing | 6.6 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 4.0 |

| Farm animal welfare | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Sports | 1.6 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 3.1 |

| Labelling meat | 2.2 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| Diplomacy | 2.9 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Imports | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| Circuses/zoos | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Exports | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Dietary choices | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Topic . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter general animal welfare regulation | 21.5 | 26.0 | 20.5 | 21.7 |

| Wildlife | 9.0 | 10.6 | 20.9 | 15.2 |

| Pets | 22.5 | 20.2 | 7.5 | 14.7 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 14.1 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 8.3 |

| Slaughter | 8.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 7.0 |

| Fireworks | 2.7 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 6.1 |

| Sentience | 0.1 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 4.7 |

| Testing | 6.6 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 4.0 |

| Farm animal welfare | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Sports | 1.6 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 3.1 |

| Labelling meat | 2.2 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| Diplomacy | 2.9 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Imports | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| Circuses/zoos | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Exports | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Dietary choices | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

Excludes miscellaneous petitions (N = 201).

Percentage of all animal welfare petitions by topic in successive Westminster Parliaments 2010–2019 (N = 2,453)a

| Topic . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter general animal welfare regulation | 21.5 | 26.0 | 20.5 | 21.7 |

| Wildlife | 9.0 | 10.6 | 20.9 | 15.2 |

| Pets | 22.5 | 20.2 | 7.5 | 14.7 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 14.1 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 8.3 |

| Slaughter | 8.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 7.0 |

| Fireworks | 2.7 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 6.1 |

| Sentience | 0.1 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 4.7 |

| Testing | 6.6 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 4.0 |

| Farm animal welfare | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Sports | 1.6 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 3.1 |

| Labelling meat | 2.2 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| Diplomacy | 2.9 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Imports | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| Circuses/zoos | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Exports | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Dietary choices | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Topic . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter general animal welfare regulation | 21.5 | 26.0 | 20.5 | 21.7 |

| Wildlife | 9.0 | 10.6 | 20.9 | 15.2 |

| Pets | 22.5 | 20.2 | 7.5 | 14.7 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 14.1 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 8.3 |

| Slaughter | 8.1 | 5.4 | 6.6 | 7.0 |

| Fireworks | 2.7 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 6.1 |

| Sentience | 0.1 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 4.7 |

| Testing | 6.6 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 4.0 |

| Farm animal welfare | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Sports | 1.6 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 3.1 |

| Labelling meat | 2.2 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| Diplomacy | 2.9 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 |

| Imports | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 2.6 |

| Circuses/zoos | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| Exports | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Dietary choices | 0.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

Excludes miscellaneous petitions (N = 201).

In addition, the petition dataset was coded for ‘direction’. Coding for direction builds on earlier feminist studies by Reingold (2000) and whether policy actors’ interventions on a topic are pro- or anti-. In the present case, this was particularly suited to analysing petitions on hunting and the so-called field ‘sports’. The subsequent phases of coding related to framing. Derived from the classic work of Erving Goffman (Goffman, 1974, p. 27), this refers to the language used by policy actors. Effectively it is a ‘schemata of interpretation’ that is concerned with the inherent meanings, sentiments, emotions, messages and criticality in relation to social and political communication (Heine and Narrog, 2015). As noted, two aspects of framing were analysed: discursive and collective action framing (CAF).

Discursive framing is concerned with persuading the issue public by evoking particular meanings, sentiments, emotions, imagery and messages. It may explicitly or immanently advance a particular understanding of a problem. In the case of discursive framing, a key goal is to be critical and persuade other policy actors of the existence of social issues. In the second phase, CAF was analysed. This is grounded in the literature on social movements. It is concerned with using language to advance ‘action-oriented sets of beliefs and meanings that inspire and legitimate the activities and campaigns of a social movement organization’ (Benford and Snow, 2000, p. 614). Here specific frames provide the motivation for social movement members to become directly engaged in working to advance causes and address problems. It can compel them to mobilise to remedy injustices (Snow et al., 1986). Tables 2 and 3 examine the framing of the petitions. Here, the analysis draws on corpus analysis used in linguistics (Baker and Egbert, 2016). They present contents analysis of the corpus of petitions in order to record the relative frequency or level of attention to the different frames in the dataset of animal welfare petitions 2010–2019. Thereby giving insight into the persuasive use of language (emotions, arguments and feelings) used by animal welfare petitioners in their discursive attempts to garner support over three Parliamentary terms.

Discursive framing in animal welfare petitions over the three Westminster Parliaments 2010–2019 (percentage of all framings, N = 1023)

| . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative frames—evocation of suffering | ||||

| Cruel(ty) | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 8.6 |

| Inhumane | 1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Pain | 0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Neglect | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Barbaric | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Fear | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Agony | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Suffer(ing) | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 8.6 |

| Kill(ing) | 1.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 8.2 |

| Positive frames—human- and non-human symbiosis | ||||

| Care/caring | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| Ethics/ethical | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Feelings | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Intelligent/intelligence | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Moral(ity) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Needs | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 4.5 |

| Protect(ion) | 2.8 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 14.4 |

| Respect | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Rights | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 |

| Save/saving | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| Sentience | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Understand(ing) | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| Welfare/well-being | 6.7 | 7.3 | 13 | 27.6 |

| . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative frames—evocation of suffering | ||||

| Cruel(ty) | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 8.6 |

| Inhumane | 1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Pain | 0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Neglect | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Barbaric | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Fear | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Agony | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Suffer(ing) | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 8.6 |

| Kill(ing) | 1.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 8.2 |

| Positive frames—human- and non-human symbiosis | ||||

| Care/caring | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| Ethics/ethical | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Feelings | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Intelligent/intelligence | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Moral(ity) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Needs | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 4.5 |

| Protect(ion) | 2.8 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 14.4 |

| Respect | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Rights | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 |

| Save/saving | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| Sentience | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Understand(ing) | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| Welfare/well-being | 6.7 | 7.3 | 13 | 27.6 |

Discursive framing in animal welfare petitions over the three Westminster Parliaments 2010–2019 (percentage of all framings, N = 1023)

| . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative frames—evocation of suffering | ||||

| Cruel(ty) | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 8.6 |

| Inhumane | 1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Pain | 0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Neglect | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Barbaric | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Fear | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Agony | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Suffer(ing) | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 8.6 |

| Kill(ing) | 1.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 8.2 |

| Positive frames—human- and non-human symbiosis | ||||

| Care/caring | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| Ethics/ethical | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Feelings | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Intelligent/intelligence | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Moral(ity) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Needs | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 4.5 |

| Protect(ion) | 2.8 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 14.4 |

| Respect | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Rights | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 |

| Save/saving | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| Sentience | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Understand(ing) | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| Welfare/well-being | 6.7 | 7.3 | 13 | 27.6 |

| . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative frames—evocation of suffering | ||||

| Cruel(ty) | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 8.6 |

| Inhumane | 1 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 |

| Pain | 0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Neglect | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| Barbaric | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Fear | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Agony | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Suffer(ing) | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 8.6 |

| Kill(ing) | 1.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 8.2 |

| Positive frames—human- and non-human symbiosis | ||||

| Care/caring | 0.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.2 |

| Ethics/ethical | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Feelings | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Intelligent/intelligence | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Moral(ity) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| Needs | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 4.5 |

| Protect(ion) | 2.8 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 14.4 |

| Respect | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Rights | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 3.1 |

| Save/saving | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 2.2 |

| Sentience | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Understand(ing) | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.3 |

| Welfare/well-being | 6.7 | 7.3 | 13 | 27.6 |

Collective action framing in animal welfare petitions over the three Westminster Parliaments 2010–2019 (percentage of all framings, N = 715)

| Category . | Frame . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | Ban | 7.7 | 5.9 | 10.3 | 23.9 |

| Regulate | 5.9 | 4.1 | 12 | 22 | |

| Legislate | 4.6 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 16.6 | |

| Control | 0.7 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 8.8 | |

| Knowledge | (Raising) Awareness | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| Monitor | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | |

| Reveal/show/evidence/ demonstrate | 2.1 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 9.1 | |

| Recognition | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 4.9 | |

| Exogenous action repertoires | Prevent | 1.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 5.3 |

| Challenge | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 | |

| Resist(ance) | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Oppose/opposition | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Category . | Frame . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | Ban | 7.7 | 5.9 | 10.3 | 23.9 |

| Regulate | 5.9 | 4.1 | 12 | 22 | |

| Legislate | 4.6 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 16.6 | |

| Control | 0.7 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 8.8 | |

| Knowledge | (Raising) Awareness | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| Monitor | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | |

| Reveal/show/evidence/ demonstrate | 2.1 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 9.1 | |

| Recognition | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 4.9 | |

| Exogenous action repertoires | Prevent | 1.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 5.3 |

| Challenge | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 | |

| Resist(ance) | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Oppose/opposition | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

Collective action framing in animal welfare petitions over the three Westminster Parliaments 2010–2019 (percentage of all framings, N = 715)

| Category . | Frame . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | Ban | 7.7 | 5.9 | 10.3 | 23.9 |

| Regulate | 5.9 | 4.1 | 12 | 22 | |

| Legislate | 4.6 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 16.6 | |

| Control | 0.7 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 8.8 | |

| Knowledge | (Raising) Awareness | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| Monitor | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | |

| Reveal/show/evidence/ demonstrate | 2.1 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 9.1 | |

| Recognition | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 4.9 | |

| Exogenous action repertoires | Prevent | 1.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 5.3 |

| Challenge | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 | |

| Resist(ance) | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Oppose/opposition | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Category . | Frame . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | Ban | 7.7 | 5.9 | 10.3 | 23.9 |

| Regulate | 5.9 | 4.1 | 12 | 22 | |

| Legislate | 4.6 | 3.9 | 8.1 | 16.6 | |

| Control | 0.7 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 8.8 | |

| Knowledge | (Raising) Awareness | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| Monitor | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.8 | |

| Reveal/show/evidence/ demonstrate | 2.1 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 9.1 | |

| Recognition | 0.6 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 4.9 | |

| Exogenous action repertoires | Prevent | 1.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 5.3 |

| Challenge | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 | |

| Resist(ance) | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Oppose/opposition | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

In terms of the periodisation of this study, rather than solely analysing post-2015 developments (when the present petition system came into effect), the analysis covers the three parliaments 2010 to 2019—thereby taking advantage of the fact that the UK parliament website includes all post-2010 petitions in a common, downloadable electronic format. This dataset covers the whole period when e-petitions emerged at Westminster and it allows greater insight into longitudinal trends and comparison between parliamentary terms. Correspondence between the authors and HoC Petitions Committee officials confirms that the 2010–2015 petitions data are comparable with the datasets for the 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 parliaments (inter alia, they cover the same broad scope of issues and are equal in status and validity to later petitions). However, two distinctions should be noted for the 2010–2015 subset. First, it does not cover the full parliamentary term—this parliament began on 25 May 2010 and as noted, the e-petitions system was launched on 4 August 2011. Secondly, the e-petitions system 2011–2015 was solely administered by government in contrast to the post-July 2015 hybrid government/parliament system. In order to increase rigor and transparency, on selected comparative measures, the following analysis provides disaggregated data for each of the three parliaments.

4. Research findings

1. What issues do petitioners want parliamentarians to address?

We address this question by considering the number of petitions submitted across animal welfare sub-fields/topics (Table 1). Over the course of the three parliaments, the most popular petition topic, one accounting for over a fifth of petitions (21.7 per cent), was generic calls for stricter general regulation of animal welfare (to be achieved by new laws, regulatory bodies and strengthened monitoring and enforcement measures). For example, ‘Give the RSPCA, Local Councils and Police more powers to tackle animal abuse’5 and, introduce ‘New Legislation to prevent Animals and Insects being maltreated on television’.6 The second most common topic was wildlife protection (15.2 per cent). The latter demands were wide ranging and included changes to the planning system (e.g. ‘reassess general aviation airfields as green belt not brown field sites’)7; restricting the use of damaging chemicals (e.g. ‘the use of pesticides in the domestic environment should be banned’)8; and preventing habitat loss (e.g. ‘Ban Chinese Lanterns’).9

Policy related to pets is the third most popular topic (14.7 per cent). Key issues include regulating ownership and educating people about animal welfare (e.g. ‘introduce Domestic Animal Licenses and Owner Education’)10; and greater controls over the sale and trade in pets (e.g. ‘Ban animals from being sold in pet shops’).11 This is followed by hunting (8.3 per cent). In terms of direction, this topic has the highest number of petitions that are anti-animal welfare in sentiment. For example, 9 per cent of the hunting petitions in the 2017–2019 parliament were calls to overturn restrictions and bans. For example, ‘Repeal the Hunting Act’,12 ‘HMG should consider culling badgers, pigeons, foxes, grey squirrels etc. that destroy the food chains and habitat of other beneficial species’,13 ‘Legalise bow hunting in the UK’14 and ‘Legalise hare coursing with a dog’.15

2(a). How does the number and nature of animal welfare petitions change over the course of the three parliaments? (b). How does the level of attention to animal welfare compare to other policy issues?

Overall, 2500 animal welfare public petitions were submitted over three terms of the UK parliament 2010–2019. In absolute terms, the mean annual number increases significantly from 125.8 and 121.5 per annum in the 2010–2015 and 2015–2017 parliaments, to 600 in 2017–2019. When the level of attention to the principal animal welfare topics (those with 50+ petitions during any one parliamentary term) is considered, there are key shifts in the level of attention to the different animal welfare sub-fields.16 In turn, this reflects changing media attention to issues, greater reporting of animal abuse, legal and policy gains, as well as exogenous campaigns by civil society groups. For example, when the number of petitions in the 2010–2015 parliament is compared with the 2015–2017 parliament, there is a fivefold increase in the numbers of petitions on fireworks, and a threefold increase on wildlife protection, and animal use in sports.

However, the foremost example of shifting salience over time is animal sentience. It is largely neglected in the first two parliaments, yet it is the subject of over 100 petitions in 2017–2019. The explanation for this rapid increase is partly Brexit-related. It reflects worries that the EU Withdrawal Act 201817 did not include provision to transfer the principle contained in Article 13 of the Lisbon Treaty18 recognising animals as sentient beings into UK legislation. Animal welfare campaigners expressed major concerns because UK law, principally the Animal Welfare Act 2006, does not explicitly recognise the term.19 The significance of this growth in petitioning on sentience is that it offers the potential for a new conceptual approach to how animals are recognised in policy and law (i.e. they are no longer solely regarded as property, but as conscious, feeling, sentient beings). Viewed from a LFP (see below), it also shows that petitions may shape policy change. This follows because one petition (‘Recognise animal sentience and require that animal welfare has full regard in law’)20 received 103,918 signatures, thereby entitling it to a parliamentary debate in March 2019.21 In response to cross-party support in the Commons debate, the Government made a promise that, ‘the sentience of animals will continue to be recognised and protections strengthened when we leave the EU’.22 Yet, it should be noted that—notwithstanding the earlier publication of the Animal Welfare (Sentencing and Recognition of Sentience) Draft Bill,23 to date, the government has yet to make good its promise.

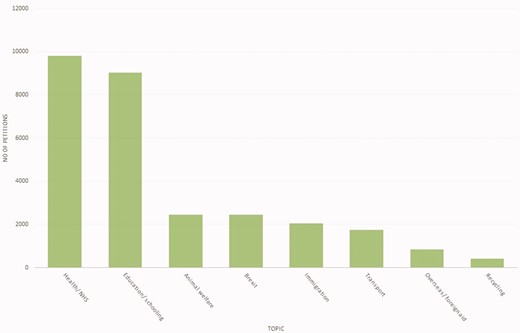

As Figure 1 reveals, when compared with the level of attention to other policy issues, over the period studied, the data show animal welfare to be a mainstream policy issue. While not the subject of as many petitions as key policy areas such as health and education, it nevertheless attracts more topics such as Brexit, immigration, transport, overseas/foreign aid and waste recycling.

Animal welfare compared with the level of attention to other policy issues (number of petitions), 2010–2019

3. How do petitioners frame their claims?

Here, we address this question by analysing two types of framing: discursive and collective action. As noted, the former aims to persuade policy actors of the existence of social issues by deliberate use of language. In contrast, CAF centres on offering appropriate solutions to issues identified in the discursive framing through activism to secure legal and policy change (Pedriana, 2006; Daviter, 2007).

As Table 2 reveals, the discursive frames fall into two broad groupings: ‘Negative frames—Evocation of suffering’ and ‘Positive frames—human- non-human symbiosis’. Axiomatically, the lead frame was animal well-being (27.6 per cent of all frames, N = 1023) (Table 2). This was followed by frames that emphasise animals’ vulnerability at the hands of humans. For example: protection (14.4 per cent, e.g. ‘Increase the maximum sentence for animal cruelty charges… The law is failing to adequately protect animals and ensure that punishment administered to those responsible for acts of cruelty fits the crime)24; suffering (8.6 per cent, e.g. ‘End the Cage Age: ban cages for all farmed animals … Across the UK, millions of farmed animals are kept in cages, unable to express their natural behaviours. This causes huge suffering …’)25 and cruelty (8.6 per cent, e.g. ‘The Government must end the cruel practice of puppy/kitten farming in the UK’.26

A significant strand of the petitions discourse is framed in terms of sentience (6.3 per cent). Here, it is instructive to examine how petitioners combine frame use. For example, the case for recognising sentience in UK law is repeatedly made by referring to humans’ duty to animals and, the ethical dimension to how we treat animals. For example, ‘We call for a new independent Animal Welfare Advisory Council to provide advice to all government ministers at the UK and devolved level, including through animal welfare impact assessments. This body would support governments in fulfilling their duties to animals, ensuring decisions are underpinned by the best scientific and ethics expertise’.27

In the case of CAF three groupings emerge (Table 3). The largest, constituting almost three-quarters of all CAF frames (N = 715), relates to administration (and the constituent frames: ban, regulate, legislate, control), 71.3 per cent. The second is about knowledge of animal welfare and constitutes almost a quarter of the total (and the constituent frames recognition: (raising) awareness, reveal/show/evidence/demonstrate, monitor), 22.1 per cent. The third relates to exogenous action repertoires (and the constituent frames: prevent, stop, oppose/opposition, challenge and resist(ance), 6.5 per cent). The administration discourse is typified by, ‘Tougher prison sentencing for murdering and baiting animals and acts of cruelty… Lifetime ban from keeping any animals’.28 The knowledge discourse is typified by ‘Compulsory Microchip Scanning on pets … We need your signature to show the Government that we want a full reunification service available to protect us and our pets, otherwise what is the point of us microchipping our pets?’29 And the action repertoire discourse is typified by ‘Tougher prison sentencing for murdering and baiting animals and acts of cruelty … People cannot play God and take the lives of our animals, it’s not right, it’s not humane and these crimes need stopping’.30

4(a). Which issues gain the most support?

In addressing this question, this study underlines the need for scholarly analysis of public petitions to distinguish between the number of petitions on an issue and the level of support as measured by a number of signatures. In the latter case, the top ten petitions with the highest numbers of signatures span the following categories: fireworks, generic—stricter regulation, hunting, pets and slaughter (Table 4). Some of the issues in this list clearly will have received more signatures because the animal protection issue overlaps with a non-animal protection concern. For instance, many petitioners will have signed the fireworks petition because they are increasingly a public nuisance, rather than primarily because of animal protection. In like fashion, religious conviction may have led to the signing of the only mass support petition coded as ‘anti-animal welfare’—namely, ‘Protect religious slaughter in the UK and EU’.

The top ten animal welfare petitions: those with the highest numbers of signatures 2010–2019

| Parliament . | Title . | Topic . | Number of Signatures . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–2019 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public. Displays for licenced venues only. | Fireworks | 307,897 |

| 2017–2019 | Ban fireworks for general sale to the public. | Fireworks | 305,579 |

| 2010–2015 | Stop the badger cull | Hunting | 304,255 |

| 2017–2019 | Reject calls to add Staffordshire Bull Terriers to the Dangerous Dogs Act | Pets | 186,226 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public and only approve organised displays. | Fireworks | 168,160 |

| 2010–2015 | Protect religious slaughter in the UK and EU | Slaughter | 135,408 |

| 2015–2017 | Give status to Police Dogs and Horses as ‘Police Officers’ | Generic—stricter AW regulation | 127,729 |

| 2010–2015 | Harvey's Law | Pets | 123,307 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban driven grouse shooting | Hunting | 123,077 |

| 2010–2015 | End non-stun slaughter to promote animal welfare | Slaughter | 118,956 |

| Parliament . | Title . | Topic . | Number of Signatures . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–2019 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public. Displays for licenced venues only. | Fireworks | 307,897 |

| 2017–2019 | Ban fireworks for general sale to the public. | Fireworks | 305,579 |

| 2010–2015 | Stop the badger cull | Hunting | 304,255 |

| 2017–2019 | Reject calls to add Staffordshire Bull Terriers to the Dangerous Dogs Act | Pets | 186,226 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public and only approve organised displays. | Fireworks | 168,160 |

| 2010–2015 | Protect religious slaughter in the UK and EU | Slaughter | 135,408 |

| 2015–2017 | Give status to Police Dogs and Horses as ‘Police Officers’ | Generic—stricter AW regulation | 127,729 |

| 2010–2015 | Harvey's Law | Pets | 123,307 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban driven grouse shooting | Hunting | 123,077 |

| 2010–2015 | End non-stun slaughter to promote animal welfare | Slaughter | 118,956 |

The top ten animal welfare petitions: those with the highest numbers of signatures 2010–2019

| Parliament . | Title . | Topic . | Number of Signatures . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–2019 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public. Displays for licenced venues only. | Fireworks | 307,897 |

| 2017–2019 | Ban fireworks for general sale to the public. | Fireworks | 305,579 |

| 2010–2015 | Stop the badger cull | Hunting | 304,255 |

| 2017–2019 | Reject calls to add Staffordshire Bull Terriers to the Dangerous Dogs Act | Pets | 186,226 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public and only approve organised displays. | Fireworks | 168,160 |

| 2010–2015 | Protect religious slaughter in the UK and EU | Slaughter | 135,408 |

| 2015–2017 | Give status to Police Dogs and Horses as ‘Police Officers’ | Generic—stricter AW regulation | 127,729 |

| 2010–2015 | Harvey's Law | Pets | 123,307 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban driven grouse shooting | Hunting | 123,077 |

| 2010–2015 | End non-stun slaughter to promote animal welfare | Slaughter | 118,956 |

| Parliament . | Title . | Topic . | Number of Signatures . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–2019 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public. Displays for licenced venues only. | Fireworks | 307,897 |

| 2017–2019 | Ban fireworks for general sale to the public. | Fireworks | 305,579 |

| 2010–2015 | Stop the badger cull | Hunting | 304,255 |

| 2017–2019 | Reject calls to add Staffordshire Bull Terriers to the Dangerous Dogs Act | Pets | 186,226 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban the sale of fireworks to the public and only approve organised displays. | Fireworks | 168,160 |

| 2010–2015 | Protect religious slaughter in the UK and EU | Slaughter | 135,408 |

| 2015–2017 | Give status to Police Dogs and Horses as ‘Police Officers’ | Generic—stricter AW regulation | 127,729 |

| 2010–2015 | Harvey's Law | Pets | 123,307 |

| 2015–2017 | Ban driven grouse shooting | Hunting | 123,077 |

| 2010–2015 | End non-stun slaughter to promote animal welfare | Slaughter | 118,956 |

In aggregate, over the three parliaments, of all categories, generic calls for stricter general regulation of animal welfare gain most of the 5.7 million signatures31 of support (almost a fifth of the total, 19.3 per cent) (Table 5). It was also first-ranked in terms of the number of signatures. However, subsequent topics see a marked divergence between the number of petitions and the level of support measured by numbers of signatures. Thus, the second-ranked animal welfare topic by a number of signatories was hunting (15 per cent of signatures); in contrast, it was ranked fourth in terms of number of petitions. Fireworks were ranked third and attracted 14.8 per cent of signatures (compared with being ranked sixth on petition numbers). Animal exports were 8th-ranked in terms of signatories (compared with 15, as measured by number of petitions). The greatest discrepancy in the ranking of topics is in the case of wildlife which is ninth-ranked, attracting 3.5 per cent of signatures, compared with being second-ranked based on numbers of petitions. The significance of these differences is that they suggest animal welfare sub-fields’ contrasting tactical approaches to campaigning using the petitions system. The data indicate that when petitions fail to attract mass support, there may be a switch of tactics to submitting multiple petitions on the same point to give prominence to an issue in petitions listings (this might be dubbed ‘petition-bombing’). It is relatively easy to achieve. While petitions with exactly the same title as an existing one will be rejected, the current data set provides many examples where minor changes—such as the addition to the same core wording of exclamation marks and different adjectives, allows them to be recorded as separate new petitions (provided they gain five or more signatures).

Percentage of all signatories to animal welfare petitions to Westminster 2010–2019 (N = 5,768,005)a

| . | Ranking Number of signatures . | Ranking Number of petitions) . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter animal welfare regulation | 1 | 1 | 4.36 | 5.14 | 9.83 | 19.33 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 2 | 4 | 5.93 | 5.40 | 3.61 | 14.94 |

| Fireworks | 3 | 6 | 0.74 | 5.13 | 8.92 | 14.79 |

| Pet regulation | 4 | 3 | 6.03 | 3.42 | 3.76 | 13.21 |

| Slaughter | 5 | 5 | 6.95 | 0.90 | 2.04 | 9.89 |

| Sports | 6 | 10 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 5.64 | 6.19 |

| Farm animal welfare | 7 | 9 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 4.50 | 5.29 |

| Exports | 8 | 15 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.77 | 3.96 |

| Wildlife | 9 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 2.37 | 3.54 |

| Imports | 10 | 13 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 2.25 | 2.79 |

| Sentience | 11 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.12 | 2.12 |

| Testing | 12 | 8 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 1.15 | 1.76 |

| Labelling meat | 13 | 11 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 1.20 |

| Dietary choice | 14 | 16 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1.03 |

| Diplomacy | 15 | 12 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| Circuses/zoos | 16 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| . | Ranking Number of signatures . | Ranking Number of petitions) . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter animal welfare regulation | 1 | 1 | 4.36 | 5.14 | 9.83 | 19.33 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 2 | 4 | 5.93 | 5.40 | 3.61 | 14.94 |

| Fireworks | 3 | 6 | 0.74 | 5.13 | 8.92 | 14.79 |

| Pet regulation | 4 | 3 | 6.03 | 3.42 | 3.76 | 13.21 |

| Slaughter | 5 | 5 | 6.95 | 0.90 | 2.04 | 9.89 |

| Sports | 6 | 10 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 5.64 | 6.19 |

| Farm animal welfare | 7 | 9 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 4.50 | 5.29 |

| Exports | 8 | 15 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.77 | 3.96 |

| Wildlife | 9 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 2.37 | 3.54 |

| Imports | 10 | 13 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 2.25 | 2.79 |

| Sentience | 11 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.12 | 2.12 |

| Testing | 12 | 8 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 1.15 | 1.76 |

| Labelling meat | 13 | 11 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 1.20 |

| Dietary choice | 14 | 16 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1.03 |

| Diplomacy | 15 | 12 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| Circuses/zoos | 16 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

Excludes miscellaneous petitions.

Percentage of all signatories to animal welfare petitions to Westminster 2010–2019 (N = 5,768,005)a

| . | Ranking Number of signatures . | Ranking Number of petitions) . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter animal welfare regulation | 1 | 1 | 4.36 | 5.14 | 9.83 | 19.33 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 2 | 4 | 5.93 | 5.40 | 3.61 | 14.94 |

| Fireworks | 3 | 6 | 0.74 | 5.13 | 8.92 | 14.79 |

| Pet regulation | 4 | 3 | 6.03 | 3.42 | 3.76 | 13.21 |

| Slaughter | 5 | 5 | 6.95 | 0.90 | 2.04 | 9.89 |

| Sports | 6 | 10 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 5.64 | 6.19 |

| Farm animal welfare | 7 | 9 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 4.50 | 5.29 |

| Exports | 8 | 15 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.77 | 3.96 |

| Wildlife | 9 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 2.37 | 3.54 |

| Imports | 10 | 13 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 2.25 | 2.79 |

| Sentience | 11 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.12 | 2.12 |

| Testing | 12 | 8 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 1.15 | 1.76 |

| Labelling meat | 13 | 11 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 1.20 |

| Dietary choice | 14 | 16 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1.03 |

| Diplomacy | 15 | 12 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| Circuses/zoos | 16 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| . | Ranking Number of signatures . | Ranking Number of petitions) . | 2010–2015 . | 2015–2017 . | 2017–2019 . | All . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generic—stricter animal welfare regulation | 1 | 1 | 4.36 | 5.14 | 9.83 | 19.33 |

| Hunting/culling/trapping | 2 | 4 | 5.93 | 5.40 | 3.61 | 14.94 |

| Fireworks | 3 | 6 | 0.74 | 5.13 | 8.92 | 14.79 |

| Pet regulation | 4 | 3 | 6.03 | 3.42 | 3.76 | 13.21 |

| Slaughter | 5 | 5 | 6.95 | 0.90 | 2.04 | 9.89 |

| Sports | 6 | 10 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 5.64 | 6.19 |

| Farm animal welfare | 7 | 9 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 4.50 | 5.29 |

| Exports | 8 | 15 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.77 | 3.96 |

| Wildlife | 9 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 2.37 | 3.54 |

| Imports | 10 | 13 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 2.25 | 2.79 |

| Sentience | 11 | 7 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.12 | 2.12 |

| Testing | 12 | 8 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 1.15 | 1.76 |

| Labelling meat | 13 | 11 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 1.20 |

| Dietary choice | 14 | 16 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 1.03 |

| Diplomacy | 15 | 12 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.29 |

| Circuses/zoos | 16 | 14 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

Excludes miscellaneous petitions.

4(b). How does government respond to the most popular petitions?

As Table 6 reveals, there were 93 mass support animal welfare petitions. Seventy gained 10,000+ signatures and 23 had over 100,000 signatures. The government response to these falls into five categories. Almost three-quarters (72 per cent) of responses were to the effect that ‘existing policy is adequate; no policy change is needed’. For example, the response to ‘Ban Greyhound Racing’ was ‘the Government has no plans to ban greyhound racing’.32 This suggests that when submitting petitions, the majority of petitioners fail to take into account the low probability of achieving policy change. A minority (7.5 per cent) of government responses said that ‘policy change is planned in line with the petition’. For example, ‘Pass legislation making animals legally “Sentient Beings” in UK law’. Government response: ‘The government is committed to the very highest standards of animal welfare as we leave the EU. We have published a draft Bill which clearly recognises animal sentience in domestic law’.33 One-in-twenty responses told petitioners that the ‘Government does not have the powers to meet petition demands’. For example, ‘The British Ambassador in Seoul has raised the issue of the dog meat trade with the Republic of Korea authorities. It is a matter for the authorities in each country to introduce and enforce the necessary legislation to end the ill treatment of animals’.34 In two instances, petitioners were informed, ‘Parliament is to be given a vote on the petition demand’. For example, ‘There is a manifesto commitment to give Parliament the opportunity to repeal the Hunting Act 2004 on a free vote with a government bill in government time.’35

Westminster governments’ response to mass-support animal welfare petitions over three Parliaments; 2010–2015, 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 (N = 4,890,317 signatures)

| Category of mass support petition/parliamentary term . | Number of mass support petitions/parliamentary term . | Government response category . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing policy adequate: no policy change needed . | Policy being updated but falls short of petition demands . | Policy change planned in line with the petition . | Government does not have the powers to meet petition demands . | Parliament to be given a vote on the petition demand . | No Govt. response† . | ||

| 2010–2015 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 19 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015–2017 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 22 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017–2019 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 29 | 20 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 11 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 70 | 47 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 23 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Category of mass support petition/parliamentary term . | Number of mass support petitions/parliamentary term . | Government response category . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing policy adequate: no policy change needed . | Policy being updated but falls short of petition demands . | Policy change planned in line with the petition . | Government does not have the powers to meet petition demands . | Parliament to be given a vote on the petition demand . | No Govt. response† . | ||

| 2010–2015 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 19 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015–2017 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 22 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017–2019 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 29 | 20 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 11 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 70 | 47 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 23 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Parliamentary business curtailed—election called.

Westminster governments’ response to mass-support animal welfare petitions over three Parliaments; 2010–2015, 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 (N = 4,890,317 signatures)

| Category of mass support petition/parliamentary term . | Number of mass support petitions/parliamentary term . | Government response category . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing policy adequate: no policy change needed . | Policy being updated but falls short of petition demands . | Policy change planned in line with the petition . | Government does not have the powers to meet petition demands . | Parliament to be given a vote on the petition demand . | No Govt. response† . | ||

| 2010–2015 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 19 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015–2017 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 22 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017–2019 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 29 | 20 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 11 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 70 | 47 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 23 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Category of mass support petition/parliamentary term . | Number of mass support petitions/parliamentary term . | Government response category . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing policy adequate: no policy change needed . | Policy being updated but falls short of petition demands . | Policy change planned in line with the petition . | Government does not have the powers to meet petition demands . | Parliament to be given a vote on the petition demand . | No Govt. response† . | ||

| 2010–2015 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 19 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2015–2017 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 22 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2017–2019 | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 29 | 20 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 11 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All | |||||||

| 10,000+ signatures | 70 | 47 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 |

| 100,000+ signatures | 23 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Parliamentary business curtailed—election called.

Of the 23 animal welfare petitions that received over 100,000 signatures (3,309,762 signatures in total), the 3 most popular topics were fireworks, general stricter animal welfare regulation and hunting (each 4 petitions, 17.4 per cent). These were followed by pets and slaughter (both 3 petitions, 13 per cent). In addition, live exports, farm animal welfare, sentience, sports and imports each attracted one 100,000+ signature petition. As with the 10,000+ signature petitions, in the majority of cases (87 per cent), government refused petitioners’ demands saying that existing policy was adequate (e.g. in response to ‘Pet Theft Reform: Amend animal welfare law to make pet theft a specific offence’, 117,453 signatures, the government said ‘The theft of a pet is already a criminal offence under the Theft Act 1968 and the maximum penalty is seven years imprisonment. An amendment to the Animal Welfare Act 2006 is not, therefore, necessary’).36

The issue of fireworks and animal welfare provides an interesting case because notwithstanding mass support for petitions on the subject, they were rejected by successive governments. Thus, in 2016 the petition ‘Restrict the use of fireworks to reduce stress and fear in animals and pets’ gained 104,038 signatures and was debated by Parliament.37 Subsequently, in 2017 ‘Ban the sale of fireworks to the public and only approve organised displays’ (168,160 signatures) was denied a HoC debate because it had recently been the subject of a debate.38 In the next parliament (2017–2019), there were three similar petitions (‘Change the laws governing the use of fireworks to include a ban on public use’, 113,284 signatures;39 ‘Ban fireworks for general sale to the public’, 305,579 signatures;40 and ‘Ban the sale of fireworks to the public. Displays for licenced venues only’, 307,897 signatures).41 The issue was again debated by Parliament and once more the government refused to change existing policy and law, noting, ‘There is legislation in place that controls the sale, use and misuse of fireworks; we have no plans to extend this further’.42

In only two cases did the government respond to 100,000+ signature petitions saying policy change was planned in line with the petition: ‘End the export of live farm animals after Brexit’43 (100,752 signatures), and ‘Recognise animal sentience and require that animal welfare has full regard in law’ (103,918 signatures—see above).44 In the former case, from 2014 to 2018, the UK exported £2.4bn worth of live animals, of which 66 per cent were to EU countries (Ares, 2019). This petition demanded that the UK Government should plan legislation to ban the export of live farm animals in favour of a carcass only trade and introduce it as soon as the UK left the EU. The underlying reason for the petition was that ‘long distance travel causes enormous suffering’.45 Notwithstanding that this is a partly devolved matter in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (see e.g. The Welfare of Animals (Transport) (Wales) Order 2007),46 following a parliamentary debate, the government’s response said, ‘animals should be slaughtered as close as practicable to their point of production. A trade in meat and meat products is preferable to the long-distance transport of animals to slaughter. Once we leave the European Union, and in line with our manifesto commitment, we can take early steps to control the export of live farm animals for slaughter’. Formal policy consultations on legislating on the issue began in December 2020 between the UK and Welsh governments, with further consultations planned with the Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Executive.47

5(a). What are the main reasons that petitions are rejected?

5(b). What do the data tell us about the (multi-level) ‘governance literacy’ of petitioners?

In the 2017–2019 parliament, two-thirds (66.1 per cent, N = 793) of animal welfare petitions were rejected by the Petitions Committee.48 In most cases, it was because there was already a petition on the same issue (60.4 per cent, N = 479). The other main rejection reasons were: it was not clear what the petition was asking for (25 per cent, N = 199), the subject of the petition was neither the responsibility of the UK government nor Parliament (13.5 per cent, N = 107) or the petition was created using a fake or incomplete name (1 per cent). These statistics underline that many petitions are misguided.

Examination of the petitions rejected because they were not the responsibility of the UK government or Parliament provides insight into the multi-level governance (MLG) ‘literacy’ of petitioners. The analysis shows that this is a problem. Almost a third (29 per cent) of petitions in this category were either the responsibility of local government (20.6 per cent), the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governments and/or legislatures (6.5 per cent), or the EU/EC (European Union/ European Commission) (1.9 per cent). Further MLG reasons for rejection of petitions included that they were the responsibility of third or voluntary sector organisations—including charitable bodies (5.6 per cent) (e.g. ‘The Greyhound Board of Great Britain is responsible for regulating the welfare and care of all racing greyhounds’)49; private companies (19.6 per cent) (e.g. ‘This is the responsibility of social media companies’)50; or were international matters (8.4 per cent) (e.g. ‘The hunting of wild animals outside the UK is the responsibility of the government in that country’).51

6. What do we know about whether animal welfare petitions are submitted by NGOs as opposed to individuals?

Data constraints mean that addressing this question by coding all the petition data and disaggregating NGOs’ petitions from those by other petitioners is not possible. The HoC Petitions Committee is not permitted to publish petitioners’ names or affiliations on archived petitions. However, analysis of the subset of mass support petitions (100,000+ signatures) does provide some insight into the balance of petitions submitted by NGOs compared with those submitted by individuals. The reason for this is their public prominence. The data sources potentially allowing the petitioners to be identified include the data packs (or briefing materials) for MPs (Members of Parliament) on each mass support petition prepared by the HoC Library ahead of parliamentary debates52; the websites of animal welfare NGOs; social media platforms and mass media reporting (TV, websites, newspapers and radio).53

This analysis revealed that of the 23 animal welfare petitions achieving 100,000+ signatures, almost two-thirds (65.2 per cent) were submitted by NGOs (or named individuals on behalf of NGOs); (21.7 per cent) were submitted by unaffiliated individuals (as in the case of the ‘Harvey’s Law’ petition)54 and in three cases (13 per cent), we were unable to deduce whether the petition was submitted by/or on behalf of, an NGO as opposed to an individual. The significance of NGOs’ predominance in submitting mass support petitions is discussed in the Conclusion section (see below).

5. Westminster animal welfare petitions: a legislative functions perspective

As the foregoing analysis shows, very few petitions secure the policy change desired by petitioners. However, Leston-Bandeira’s (2019) seminal LFP takes a broader view and is predicated on offering a fuller understanding of the wider democratic role that e-petitions systems play. Here, we test this proposition by applying the animal welfare data set to the LFP framework. We seek to determine whether the data support the four key roles proposed in Leston-Bandeira’s analytical framework: linkage, campaigning, scrutiny and policy.

5.1 Linkage roles

As the following analysis reveals, in this section, our data set provides evidence of the six linkage roles that petitions play in shaping the direct relationship between citizens and parliament.

Legitimacy. In the face of citizens’ diverse options—or ‘repertoires of contention’ (Tilly 2003) for pressing policy claims on parliamentarians (e.g. direct action, civil disobedience, violent protest, boycotts), even those concerned with the most contentious sub-fields of animal welfare such as animal testing and hunting use the petitions system. This is significant for it signals petitioners’ recognition of the legitimacy of parliament and its authority to deal with issues raised by civil society. For example, ‘I implore the UK government to illegalise the importing of foie gras products in the UK. Give the British people a voice!’55

Safety valve. The current case study also reveals how petitions perform an important safety valve role, whereby the submission and signing of the e-petition helps to disperse tension. Examples include protest directed at government ministers: ‘It is time for Owen Paterson to resign as Environment Secretary due to his promotion of the badger cull, and desire to see fox hunting return’.56

Grievance resolution. This linkage role suggests different means of grievance resolution. This example is in relation to perceived injustice and the past policy record of individual parliamentarians. For example, ‘We call on PM Theresa May to sack Lord Gardiner of Kimble and Mark Casale’ (during the inquiry into Breed Specific Legislation, the named individuals classed dogs in rehoming centres seized and destroyed for being ‘of type’ as ‘Collateral Damage’ in upholding current Dangerous Dogs Act Section 1 banned breeds).57

Education. This is a further linkage function performed by petitioning that can variously inform and initiate citizen action on issues such as animal welfare. The data set provides numerous examples, ‘we demand compulsory education teaching children how to look after animals’.58

Public engagement. With over six million signatures, the animal welfare data evidence how the petitions systems can effectively promote public engagement and further the representation of the interests of different groups and issues. For example, ‘Change the Law so People who Abuse Animals go to Prison … We are a Voice for Animals that have been Abused, Neglected, and have even died because of Cruelty—there should be a change in the law …’59

Political participation. The animal welfare data demonstrate how petitions allow citizens to participate in setting Parliamentary business. For example, the petition ‘Parliamentary debate on animal experiments’ noted that ‘in 2010 the UK used over 3.6 million animals in experiments: a 25-year high’. It continued, ‘We believe this should be subject to Parliamentary debate, since a great deal of public money is spent on animal experiments and it is an issue the public are extremely concerned about’.60

5.2 Campaigning roles

As Leston-Bandeira’s framework reveals, the e-petitions system also performs four campaigning roles: helping to mobilise support, strengthening a group’s identity, as well as promoting dissemination and recruitment. Each is evidenced by the case study data.

Mobilisation. The animal welfare data include numerous calls for mobilisation. For example, ‘The Government needs to support the RSPCA’61 and ‘Launch a national campaign promoting the health benefits of a vegan lifestyle’.62

Group identity strengthening. This is also evidenced in the case study data. For example, ‘Amend equality legislation for vegans and vegetarians’.63 Here, campaigners are calling on government to make sure that vegans and vegetarians are given equal rights to other protected characteristics identity groups under the Equality Act 2010.

Dissemination. The animal welfare data also show how the e-petitions system can act to promote the dissemination of key issues. For example, the data set includes numerous road safety calls for government to ‘Show Horse Awareness Adverts on Television’.64

Recruitment. The present data also evidence the use of petitions to recruit supporters to advance animal welfare causes. For example, the petition ‘Harvey’s Law’ (inter alia, requesting legislation requesting the Highways Agency to scan the remains of all domestic animals retrieved from the highways) ends with the rejoinder ‘Please join us!’65

5.3 Scrutiny

The present data also provide evidence of the third legislative function that the Westminster e-petitions system performs—namely, scrutiny in the form of acting as a ‘fire-alarm’, agenda setting, evidence gathering and questioning.

Fire-alarm. As Leston-Bandeira (2019, p. 430) notes, this role ‘enables the raising of issues to policymakers from bottom-up … highlighting issues dispersed across the country, of no particular significance within specific constituencies’. The present data analysis shows how this scrutiny role is germane to animal welfare petitions. Examples include, ‘Rabies alert-all UK pet dogs and cats are at risk from rabies as Europe insist we lose our unique status-no rabies for 100 years’66 and ‘Emotional Assistance Pet Act Urgently Needed’.67

Agenda setting. The current data set provides ample evidence of this function. The petitions call repeatedly on government and parliament to add new items to their agendas. For example, ‘Introduce a no-kill policy for all pet type animals’,68 ‘Introduce teaching Animal sentience at all public and private schools’69 and introduce ‘New Legislation to prevent Animals and Insects being maltreated on television’.70

Evidence gathering. Again, the data set supports this aspect of the LFS framework. The diverse examples include ‘Provide scientific evidence to support exclusion of animal sentience from UK law’71; ‘Reconsider, using scientific evidence, that animals cannot feel pain or emotions’72 and ‘Require DEFRA to fund research into the cause/s of Alabama Rot (CRGV) in dogs’.73

Questioning is the final scrutiny role highlighted by the LFP framework. The current data set validates it as a key function of parliamentary petitions. For example, ‘I request that you put the question of sentience to the people via referendum’.74

5.3.1 Policy influencing

Lastly, the current data set supports the LFP framework in relation to the petitions system’s four policy roles: review, improvement, influence and change.

Policy review. In contrast to un-evidenced demands for government to agree to petitioners’ demands, a core strand of the case study data calls for policy review in order to effect change. For example: ‘Review RSPCA Governance Failure to Abide by Provisions of the Animal Welfare Act’75 and ‘Review the laws and regulations regarding animal welfare in the UK food industry’.76

Policy improvement. The animal welfare data reveal manifold examples of exogenous demands for enhancing policy. For example: ‘Introduce Animal services to the 999 emergency services’77 and ‘Give status to Police Dogs and Horses as 'Police Officers’’ (arguing that the UK should fall in line with practice in North America and elsewhere).78

Policy influence. Animal welfare petitions also demonstrate how petitioners draw upon individual and organisational knowledge in their attempts to shape government policymaking. Examples include: ‘Campaign for silent fireworks’,79 ‘Launch a national campaign promoting the health benefits of a vegan lifestyle’80 and ‘Campaign for the reintroduction of extinct species in Britain’.81

Policy change. As extant public petitions research notes, a small proportion of petitions lead directly to policy change. The present case study shows that animal welfare petitions are no exception. Yet, as the foregoing analysis reveals, policy change examples do exist. For example, following the petition ‘End the export of live farm animals after Brexit’,82 formal policy consultations on legislating on the issue began in December 2020.83

6. Conclusion

This study makes an original contribution by using longitudinal animal welfare data to test Leston-Bandeira’s LFP for petitions analysis. As the latter framework predicts, and our case study data show, e-petitions perform a limited role in securing policy change. Over three parliaments, and following the submission of 2500 animal welfare petitions, just two can be directly linked to changes in the law on animal welfare. Yet, as the legislative functions framework reveals, sole reliance on policy change fails to fully appreciate the wider significance of e-petitions system to contemporary parliamentary democracy. Specifically, it highlights how petitions perform four key roles: linkage, campaigning, scrutiny and policy development. In terms of linkage, the analysis evidences how the introduction of e-petitions a decade ago has re-shaped the direct relationship between civil society and parliament. Here, it should be noted that this is a nuanced process. It is not only a case of members of the public seeking to set the agenda by drafting petitions and signing them. In addition, the Westminster petitions system is also providing key opportunities for the political engagement of organised civil society. The foregoing analysis shows that NGOs draft the majority of successful petitions (those achieving more than 100,000 signatures). In turn, they use their mobilising capacity, including using e-mail lists and social media, to promote the petitions amongst their supporters. Often overlooked, this is a significant development and underlines how, in the space of a decade, the e-petitions system has had added an important new dimension to NGOs’ action repertoires (Tilly, 2006) and reshaped relations between organised civil society and the Westminster parliament. By providing a new and accessible means for civil society to press policy claims on lawmakers, the petitions system has resulted in a significant increase in citizen engagement in the setting of parliamentary business. The analysis shows how over the course of three parliaments, six million signatories demanded that parliamentarians do more to address animal welfare matters. The current analysis also demonstrates how e-petitions perform four key campaigning roles by helping to mobilise wider support for animal welfare, as well as strengthening campaigner group identity, promoting the dissemination of evidence on animal welfare and aiding the recruitment of new animal welfare advocates.

In addition, this study furthers understanding of the substantive representation of non-humans in legislative settings by revealing how public petitions have been widely adopted by animal welfare campaigners. The analysis of petitions submitted to Westminster confirms a significant increase in attention to animal welfare over the three parliaments and supports extant studies showing that animal welfare has become a mainstream policy issue in UK politics. It also reveals the nature of petitions on animal welfare. Lead petition issues include stricter general regulation of animal welfare, greater wildlife protection and improved policy on companion animals. Over the period studied, our analysis identified key shifts in campaigners’ attention to issues across and between animal welfare sub-fields, including increased focus on animal sentience. Moreover, analysis of discursive framing revealed how petitioners garnered support from the issue public by emphasising animals’ vulnerability at the hands of humans. In turn, examination of CAF revealed demand for change in three areas: administration (ban, regulate, legislate, control), improve knowledge of animal welfare (raising awareness, reveal/show/evidence/demonstrate, monitor) and exogenous interests’ action repertoires (prevent, stop, oppose/opposition, challenge and resist(ance)).