Big Tech companies, for the most part, have been able to have their cake and eat it, too.

By pitching themselves as neutral platforms that prioritize free expression—while at the same time bowing to local pressure to remove or restrict certain content—they’ve enjoyed rather broad access to nearly all the world’s markets. Even Russia, which for decades during the Soviet era fought to keep Western media out, has let them in.

That may be about to change, though.

Big Tech’s adherence to a “markets first” ideology has allowed them to largely skirt geopolitical concerns. China has stood out as a notable exception, of course, and while some companies like Apple have been able to crack the market, even their business is becoming harder. Now, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, tech companies are likely to find themselves forced to choose sides. Observers have spoken for years about a decoupling between US and China. Now, the same appears to be happening—again—between the West and Russia.

For companies that were founded after the Berlin Wall fell—including many Big Tech firms—it’s new territory. Traversing it won’t be easy, and more than a few will stumble.

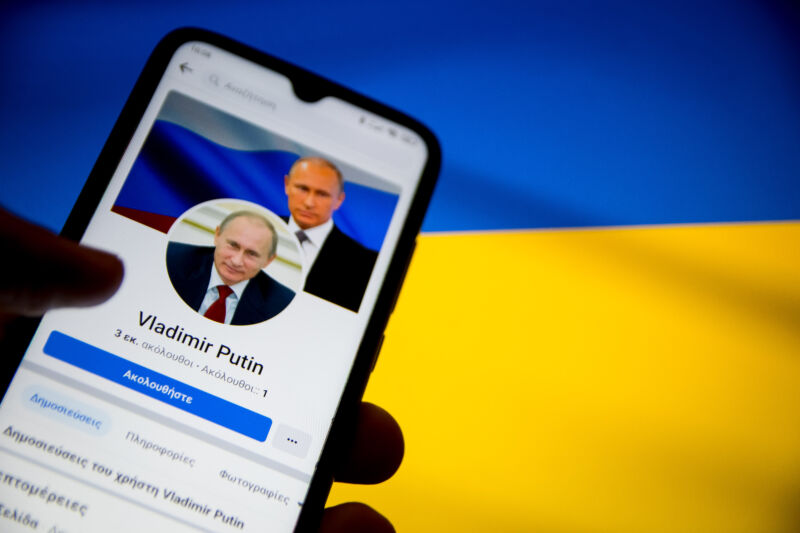

Authoritarian governments like that of Russia under Vladimir Putin have frequently pressured American tech companies to bow to their will. Russia has asked Facebook and Twitter to remove posts that encouraged anti-government protests, for example, or asked Apple and Google to remove apps intended to help opposition politicians. In some cases, those companies have complied. Western governments like the US have also asked platforms to remove posts and accounts, though in those cases they targeted inauthentic behavior from outfits like Russia’s infamous Internet Research Agency, which sought to foment domestic unrest and undermine elections by creating fake content.Now, those same companies are finding themselves ensnared in a new conflict, one with higher stakes. Unlike before, threading the needle won’t be easy. Depending on how the next few weeks play out, it may be impossible.

Some of the challenges they face aren’t new. Meta, for example, said today that it unearthed a network of dozens of fake accounts, groups, and pages that were spreading pro-Russian, anti-Ukrainian propaganda. The network’s accounts used profile pictures that were created using AI tools, and they claimed to be engineers, editors, and scientific authors writing from Kyiv. Meta said the campaign appeared to be linked to a previous one from 2020, which had been run by Russians and Russian supporters in the Ukrainian regions of Donbas and Crimea. Altogether, the network had amassed 4,000 followers on Facebook and fewer than 500 followers on Instagram before being shut down.

At the same time, Meta said that pro-Russian hackers have been stepping up their phishing attempts to break into the accounts of Ukrainian officials and journalists, an operation security researchers are calling “Ghostwriter.”

Meta’s quick action on the Russian propaganda networks and hacking rings shows that the company has gotten quicker over the years at identifying and removing inauthentic accounts and groups. But as it has started to get a handle on that problem, another is cropping up.

Governments around the world are pressuring social media companies like Meta and Twitter to fall in line with their geopolitical views. Russia has started restricting access to both Facebook and Twitter, while Western governments have been pressuring platforms to reduce the spread of Russian propaganda through tweaks of their ranking algorithms or the outright removal of accounts belonging to Russian state media. Ukraine, for example, asked YouTube to block Russia Today’s channels in the country, and Google complied. Google also said that it was preventing RT from monetizing its content on YouTube.Facebook and Twitter are used to blocking more clandestine actors like the Internet Research Agency, so the push to remove official state media is new territory for them.

They could follow government requests on an ad hoc basis, or, as Alex Stamos, former security head for Facebook, argues, they could employ “a more neutral standard” by “block[ing] state media from countries that block your platform.” That sort of tit-for-tat approach would be clear and consistent, and it would not only cover Russia Today and its myriad channels in various countries, but also China’s official mouthpieces like CGTN.

Authoritarian governments have long used democratic societies’ penchant for open discourse against them, and such a move would help to undermine that strategy and level the information battlefield somewhat.

“Why should FB/YT/TW give them tons of boost when their citizens are cut off from dissenting voices on these platforms? Time to clean house,” Stamos said. “It’s appropriate for American companies to pick sides in geopolitical conflicts, and this should be an easy call.”

reader comments

127