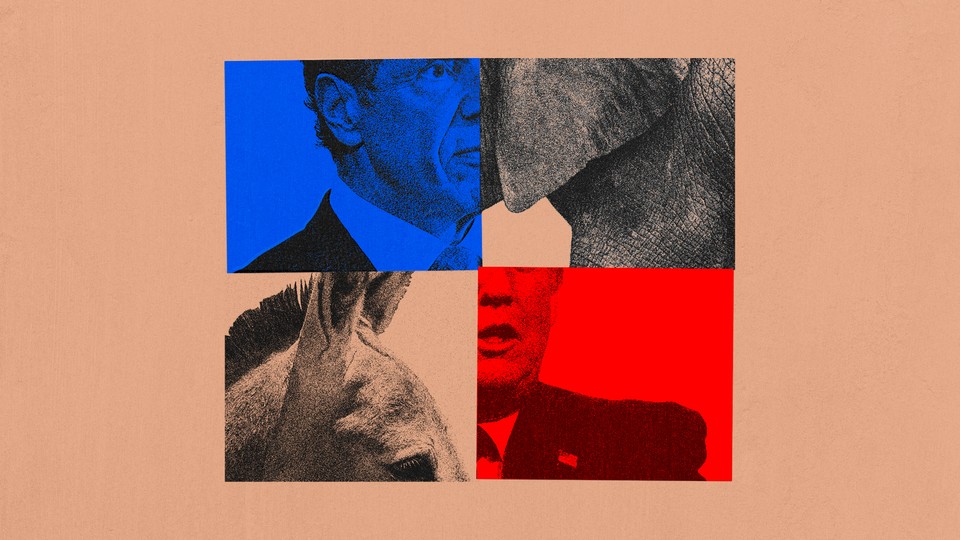

Why There’s a Partisan Split on Sexual Harassment

Democratic voters are more likely than Republicans to draw a connection between abuses of power in personal relationships and abuses of power in public office.

In 2017, in response to the Access Hollywood tape and the shock of Donald Trump’s election, I embarked on a research project. I wanted to understand how so many people could support a leader who had bragged about being a sexual predator. And I wanted to know why I experienced such visceral disgust for Trump’s character but so many others in the United States did not.

I left my job working for New York Governor Andrew Cuomo to pursue this project. After four years of studying, surveying, analyzing, writing, and editing, my work was accepted for publication in the Political Studies Review—just as seven women stepped forward to accuse my former employer of sexual harassment or assault. (Cuomo has denied the allegations.) What I found helps explain how Trump weathered 19 accusations of sexual harassment or assault with the support of his party, while Cuomo faces growing calls for his resignation. Democrats, I learned, are more likely than Republicans to believe claims of sexual harassment and assault—and more likely to conclude that a politician who commits such acts will also abuse the powers of his office in other ways.

In the study, respondents were introduced to a hypothetical candidate for office named Jamie Easton. A control group read a two-paragraph biography, while the rest of the participants read the same text with one sentence tacked on: “During the election, two former staffers went public with an accusation that Easton had groped and sexually harassed them while they worked together three years ago; it was revealed the parties settled a lawsuit about the matter.” In addition, a portion of the Republican participants were told that Easton was a member of the GOP, while a portion of the Democratic participants were told that he was a Democrat.

My co-author and I found that 37 percent of all voters were still willing to vote for Easton, despite the accusations. However, while 57 percent of Republican voters said they were willing to support such a candidate from their own party, only 39 percent of Democratic voters said the same.

Conservative respondents tended to question the validity of the allegations, or to downplay their importance. “He is a good candidate, but I would worry [whether] the allegations are true or not,” one woman said, explaining her support. “He has done really good things for his community.” Another woman was convinced “that his personal tendencies are immoral,” but also that “this is a common trait in many men—especially those in power.” She would vote for him, she added, “due to the greater good he could do … Unless there was a viable candidate that had his track record AND was morally superior, only in that case would I change my opinion.”

Liberals, for their part, tended to take the allegations at face value, and to express concern about the candidate’s abuse of power. Easton sounded qualified, one woman wrote, “but misused their authoritative position to commit a crime and possibly for some sort of biased gain.” One Democratic man was concerned that the candidate was “someone who takes advantage of his position in power,” while another wrote that the candidate was a “man in power who uses that to intimidate women.”

Like any such study, it provides a snapshot of opinion, which changes over time; in the 1990s, most Democrats responded to allegations of sexual harassment and assault against Bill Clinton in much the way that most Republicans did here. But the gap between the reactions of Democrats and Republicans today helps explain why Trump was able to sustain his position, whereas Cuomo faces significant pushback from leaders of his own party, and seems more likely to follow in the footsteps of Democrats such as former Senator Al Franken and former Representatives John Conyers and Ruben Kihuen, whose political careers ended after such allegations.

The study used a hypothetical, but it was carefully constructed to match the pattern that allegations against politicians usually follow. Many of the women who raise allegations are assistants or schedulers; they are not equal partners with the capacity to rebuff advances without fear of repercussion, and the propositions from politicians are not typically made out of romantic interest. The acts the women describe—unwanted touching, groping, harassment—take place within that relationship of unequal power. And that’s precisely the point: The propensity to sexually harass and assault women is a marker of a willingness to abuse power.

My own experience bears that out. I’ve spoken with many friends and former colleagues in recent weeks, and if one word describes our collective response to the stories of bullying and harassment by Cuomo, it’s vindication. I was not sexually harassed by Cuomo, but like others who worked in the executive chamber, I know enough to find the allegations credible, and within the range of experiences that we witnessed and withstood.

Some voters are clearly inclined to disbelieve claims of such behavior, or to dismiss them as irrelevant. But Cuomo also faces allegations of covering up the COVID-19 mortality rate in long-term-care facilities, and Trump became the first president to be impeached twice—the first time, for abusing the power of public office. The voters who rejected the hypothetical candidate believed that allegations of sexual harassment and assault—abuse of power in a personal relationship—would foreshadow other abuses of the power of public office. The evidence suggests they were right.