From the perspective of Mexico’s former President, what made Donald Trump’s abandonment of the TPP “an extreme example of folly”? From the perspective of a leading global-trade expert, what makes plurilateral engagement (rather than comprehensive agreements) the best way for Joe Biden’s new administration to gradually move forward on trade? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Bernard Hoekman and Ernesto Zedillo. This present conversation focuses on Hoekman and Zedillo’s edited collection Trade in the 21st Century: Back to the Past?

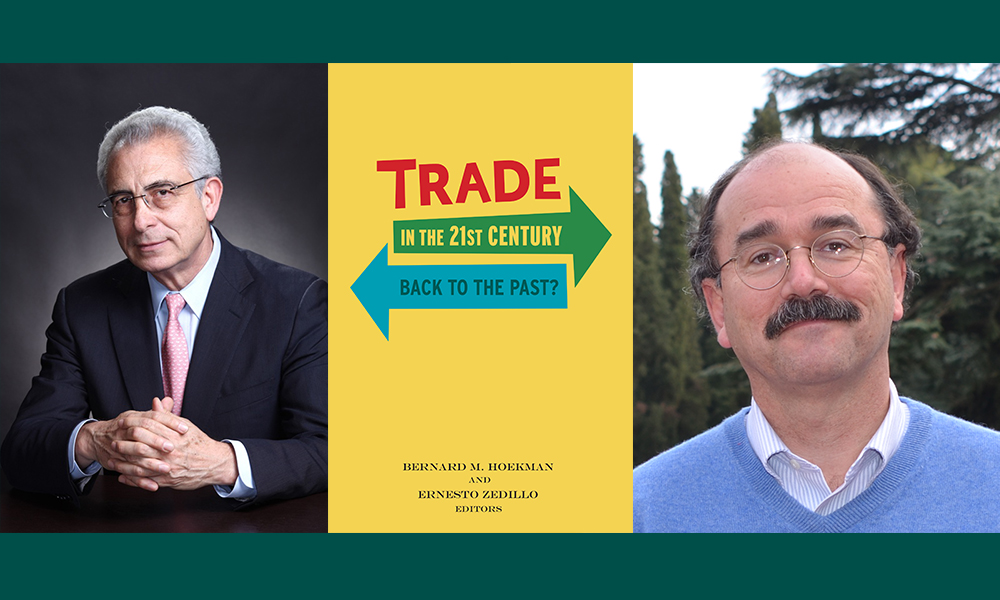

Bernard Hoekman is a Professor and Director of Global Economics in the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence (where Hoekman also serves as Dean for External Relations). Hoekman’s previous positions include Director of the International Trade Department, and Research Manager in the Development Research Group, at the World Bank. He was a member of the GATT Secretariat during the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations. A CEPR Research Fellow, as well as a senior associate of the Economic Research Forum for the Arab countries, Iran and Turkey, he has been a member of several World Economic Forum Global Future Councils.

Ernesto Zedillo is Director of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization. Zedillo is also a Professor of International Economics and Politics, and of International and Area Studies, at Yale, as well as a Professor Adjunct of Forestry and Environmental Studies. He served as President of Mexico from 1994-2000. He is a Member of The Elders (an independent group of global leaders using their collective experience and influence for peace, justice, and human rights worldwide), and the Group of 30. Zedillo is Chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation Economic Council on Planetary Health, and is an international member of the American Philosophical Society.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could we start with the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization organizing a 2011 conference on the state of the multilateral trading system, but without your conference participants “seriously entertaining” prospects for any imminent existential threat to this system? And could you sketch some driving forces which have since made that scenario possible?

ERNESTO ZEDILLO: Well as you mention, some years ago we got together at Yale with a group of reputable trade economists, basically to discuss how the trading system was looking after early 21st-century failures to strengthen it, particularly in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis.

For one thing, all of us felt frustrated that, 10 years after having been launched, the Doha Round hadn’t been by any means concluded — despite a very solemn commitment made by the G20 leaders in 2009, as part of their response to the financial crisis. By the time of our conference, the deadline they had imposed on themselves to conclude Doha negotiations had passed. Pledges to strengthen the trading system weren’t being met, precisely as reasons to do so were multiplying. There was the proliferation of new (and discriminatory) regional trade agreements, the dramatic emergence of China, and the general intensification of globalization which obviously calls for better rules of engagement. For all of these reasons, it did concern us not to see much real reform happening. But frankly, we still didn’t see any overwhelming existential threat to the whole system.

Then Donald Trump got elected, and actually began, right after taking office, to do what he’d pledged to do on trade. Eventually it became evident that the trading system had been pushed into a totally different game, under an existential threat. Our concern then became to show how bad this threat could be for every country (including the US), while also showing that there are plenty of good ideas to make the trading system work better for all. On the latter, of course, Bernard and co-authors had been working for many years, making significant contributions, some of which are included in Trade in the 21st Century.

If you look at Bernard’s chapter with Petros Mavroidis on the WTO’s dispute settlement understanding, it is clear that fixing this is not an insurmountable problem. If you look at Bernard’s chapter with Douglas Nelson on subsidies, they deal with pressing issues of the 21st century, well beyond the world of the Uruguay Round. In short, this book does not just lament the lack of reform, but really aims to demonstrate that there are viable ways to improve the system, to the benefit of all significant stakeholders.

I also should add that, for our 2011 conference, we wanted to pay special tribute to our colleague Patrick Messerlin, upon his retirement from Sciences Po. Bernard and I both have a particular appreciation for (and wanted to salute) Patrick, who for a long time was like a lone wolf in France and even continental Europe advocating for free trade.

BERNARD HOEKMAN: Part of this book’s background also relates to the world economy’s changing structure. Globalization of course gets a lot of flak nowadays. But at the same time, we’ve seen a huge shift in terms of participation by developing countries. And everybody might talk about China, but this is not just a China story. So part of the challenge now is: how do you deal with this real-world rebalancing, so that multilateral cooperation at the WTO is reinforced, rather than weakened?

Second, I would stress that despite Donald Trump’s infatuation with tariffs, we have seen that, in terms of actual trade policies, increasingly the action takes place, as economists describe it, “behind the border.” Most basically, this means that regulatory measures which differ across countries create costs for international businesses, whether or not they discriminate against foreign firms or products. This is increasingly important because of one of the biggest structural changes to trade over the past few decades: the rise of global supply chains, of global value chains. These allow firms in different countries to specialize in products and activities that then get combined into final goods. Products are no longer made in a single country. Firms source inputs from many countries. Components and products might move back and forth across borders many times. That means various countries’ regulatory regimes can have a multiplied impact. Tariffs still have a significant impact, but have been declining steadily — making the costs associated with regulatory heterogeneity more important for firms.

Third, I’d point to accelerating international trade in services. Right now of course, Andy, you’re in Colorado and Ernesto is in Connecticut and I’m in Europe. We can communicate over Zoom. We each can work from home. But this increased sophistication and digitalization of economic activity also has profound implications for trade. The very categories of what gets traded have changed. That means regulation of services has a much greater impact on global trade than in the past.

These issues should be front and center for what the WTO deals with today. But they haven’t been, largely because of an inability to manage the significant shift in power from OECD countries to the developing world. That shift has been one of the biggest impediments to success for multilateral trade negotiations. There is an urgent need to rethink the way the WTO deals with its members’ differences in capacity and level of development. It is no longer possible to treat all developing countries the same way.

The EU and the US say, for example, that China no longer should be treated like a developing country, and that it should follow the same rules of the game as they do. Of course China might disagree with that. We’ve always had these complexities within the trading system. But they have increasingly come to a head, because of the success of China and other large emerging economies — countries that do not wish to be bound to the same obligations as the EU or the US.

Here with Bernard’s own “Subsidies, Spillovers, and Multilateral Cooperation” chapter in mind, could you also outline an expansive 21st-century conception of “subsidy”? Why should we think of subsidies as in fact the most dominant form of state intervention in post-2008 international trade? Where might you see subsidies playing a legitimate role in preventing/addressing market failures of various sorts? And how might we better measure the complex cross-border and cross-sector spillover effects (both positive and negative) from this less conspicuous form of state-sponsored protectionism?

BH: Subsidies have become increasingly important. Traditional trade-policy measures like tariffs are less effective tools of protection in a world of international supply chains. In a world with extreme specialization, where everybody relies on importing much of what they need, in order to produce and to compete, tariffs are not useful. That also helps to explain why tariffs have become less common. The Trump administration’s use of tariffs can be seen as an attempt to undo the rise of value chains — as well as the rebalancing of global production and income that has occurred in tandem with trade and investment liberalization, and with a closer integration of the world economy.

Today, governments intervene more through tax incentives and subsidies to attract and retain private investment, complementing public investment in education, health, social security, and regulation — to address market failures of different types. The evidence cited in this chapter indicates that, since the global financial crisis, a majority of the measures taken by G20 countries that affect international trade flows, and that are discriminatory in nature (aimed to benefit domestic firms competing with foreign firms), are tax-subsidy measures. This is one reason why the EU, US, and Japan have engaged in trilateral discussions aimed at bolstering disciplines on the use of industrial subsidies.

Bolstering disciplines on the use of industrial subsidies gets complicated, however, by the fact that subsidies may be the most efficient policy instrument to deal with market failures, and to pursue noneconomic (social or equity) objectives. WTO rules stipulate that foreign subsidies specific to a firm or industry are either prohibited or “actionable” if they negatively affect (“injure”) domestic competitors. For example, export subsidies for manufactured goods are prohibited, and production subsidies can be offset through countervailing tariffs on subsidized imports. But the rules in the WTO were developed for a world where most production was national, not for today’s world of extensive supply chains. This makes it harder to determine who benefits from an industrial subsidy, and who loses, and what the appropriate response is to tax-subsidy policies that affect international competition.

Another complication is that specific tax and subsidy measures may be appropriate to address collective-action problems and market failures — for example, underinvestment in renewable energy or disadvantaged regions or communities. The WTO used to have a provision that exempted certain types of subsidies pursuing public-interest objectives (such as protection of the environment), but this lapsed in 1999. Governments retain significant freedom to invoke such exceptions, but their use can be contested by other countries on the basis of adverse competitive effects for firms. Yet there is an economic case to be made for considering the underlying goal of the policy measure, and the need to balance potential adverse effects for foreign producers against the potential benefit of intervention to deal with a collective-action problem.

One basic point this chapter makes is that the WTO needs to rethink subsidy disciplines, and that a first step should be to launch a working group to assess both the magnitude of different types of subsidy measures used by member countries, and their effects in distorting cross-border competition. Re-designing the rules requires a difficult balancing act. And that leads into your question’s second part, about how we assess the overall effects of governments subsidies. What effects can we see in prices? What effects can we see in terms of competition within markets? Which specific market failure does a tax-cum-subsidy measure target? Does it do so successfully? How large are any spillover effects? Are they large enough to worry about? Are they of systemic importance?

So, for example, if individual countries or if the EU puts a price on carbon, essentially to create incentives (subsidize) greener types of production, we should ask all of these questions. But right now, with our current arrangements, the only relevant question seems to be: does this policy have an effect on trade? And you don’t even have to quantify that effect. You simply can say: “Yes, this affects trade, and thus it is actionable.”

So still in terms of climate-change measures, and in terms of where to draw the line between constructively correcting for market failures, or indulging in anti-competitive (potentially counterproductive) state subsidies, what can Patrick Low’s chapter offer on the complexities of harmonizing national-level emissions targets and international trade policy — as well as on the challenges of addressing cross-border “carbon leakage”: both as a legitimate global concern, and as a frequent red herring in domestic politics?

EZ: First, let’s say we recognize that we can’t address climate change without a truly global regime, with enforceable agreements designed in very transparent and effective ways, and sending a clear signal not only for current but for future decisions. Well, the answer to all of that really boils down to agreeing eventually on a globally harmonized carbon price. We’ve already seen this point made both with enormous sophistication and with admirable simplicity. And it implies, by the way, the need to discipline the many energy subsidies that now exist all over the place, and that actually create a negative incentive for the behavior we need both within countries and across countries.

Then, having said that, we arrive at the next question of how you build such a regime. Climate-change mitigation of course remains a public good, meaning some actors always will have an incentive to wait for others to do what it takes to fix this problem. Significant issues of sovereignty also do come into play. So we’ve faced these enormous complexities when it comes to getting the level of agreement we’ve seen over the past 20 to 25 years. And now, some propositions suggest that if a group of key countries can agree on a border-adjusted carbon tax, then that would provide the incentive we need for others to enter this regime, and for us eventually to arrive at a universal system. And that reasoning does sound good to me in many ways, but you still have to be extremely careful.

We hear, for example, from Europe, that if they really want to keep moving ahead in perfecting or improving their carbon-pricing system, that system will need to include the adoption of a border tax. Well, that’s interesting. But that also poses a big challenge, because it can open the door to yet another form of protectionism. I see, especially at the global level, possibilities that if there are no clear rules and no transparency in reporting, we don’t end up solving the climate-change issue this way, so much as creating an even more fragmented trading system — and in fact a more confrontational trading system.

So it does seem urgent right now to deliberate on these questions. I see the Europeans putting much thought into how to do the right thing here. But I also still see the risk that they end up with something which actually does no good. Here Patrick Low has made an important contribution with his efforts to think through not only the potential benefits, but also the potential risks that come from using trade instruments to accomplish some broader global goal like this.

BH: On net of course we still subsidize non-renewable, polluting energy sources much more than renewable, non-polluting sources. That offers, in fact, one powerful example of why we need to think very seriously about how subsidies impact our economy and our society, both in helpful and harmful ways. Subsidies might be crucial for managing this carbon transition, but we need to manage this transition carefully. We also need to look at other environmentally questionable subsidies — not just fossil-fuel subsidies, but say with the fishing industry. It doesn’t make much sense to subsidize the depletion of important natural resources.

Now, from a different angle, and as Ernesto mentioned, we also do see efforts to promote climate-change mitigation and adaptation objectives through certain trade policies. We see attempts to create incentives for importing climate-neutral types of technologies, as opposed to more polluting technologies or energy sources or products. We’ve had ongoing negotiations for quite a while on an environmental-goods agreement, where countries would agree to eliminate tariffs on technologies and products that have the greatest impact in terms of decarbonizing our economies.

Here again, not enough progress has yet been made. But the WTO exists in order to make progress on these kinds of complex multilateral issues. The WTO could unambiguously assist countries in achieving their national emissions targets and environmental objectives. Trade policy has a role to play in doing so — through both liberalization to encourage trade in cleaner technologies, and taxation of polluting products. Again, through this environmental lens, trade policy can play its role in making that broader carbon transition possible.

So now pivoting back to your introduction, with its repeated reference to the “mysteries” of recent US trade policy, could we apply this method of tracking complex market-wide effects to a narrative perhaps more familiar to our readers, that of America’s accelerated deindustrialization since the 1970s? What case could you make for why both conservatives and progressives ought to see an economic success story here (albeit with certain glaring failures, such as the woefully inadequate support provided to those Americans most acutely displaced)? How might competition from China, for example, not only reduce consumer costs, but actually boost many nations’ long-term productivity and prosperity — at least if we can address what Alan Winters describes as the “political nightmare in distributional terms”?

EZ: Well, Bernard charged me with drafting notes for that part of the introduction, then went back and fixed my mistakes and added his own elements — so I’ll let him do the same today. So first, in those pages from the introduction, I come to the conclusion that Trump’s decisions here essentially had no coherent economic rationale. Trade in the 21st Century then further supports this conclusion in multiple chapters, trying to understand through the traditional literature on optimal tariffs and modern trade theory whether the Trump administration’s approach to China could be explained through any purely economic rationale.

Of course this doesn’t have to mean overlooking some significant underlying concerns about Chinese behavior — which, in my view, have to do more with Bernard’s points about subsidies and anti-competitive policies. So how do we best measure how Chinese policy and participation has affected markets and market competition at the local, national, and international levels? We all have to address that big question as best as we can. But I consider the whole Trump strategy wrong-headed, and weakly justified by his administration. Just take Trump’s aluminum and steel tariffs imposed on the basis of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. These were obviously ridiculous. China wasn’t an important steel exporter to the US. Instead these tariffs hit other US trade partners much harder. In the case of aluminum, tariffs hit American companies operating globally, much more than they hit Chinese companies. Trump’s national-security argument didn’t make sense. If taken all the way through the WTO dispute-settlement process, those tariffs would have been declared illegal, not unlike the situation when George W. Bush imposed the 2002 steel tariffs, and then had to suspend them a couple of years later.

Equally worrisome (or even more so) were the Trump administration’s investigation and subsequent tariffs under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which really started this massive trade war between the two countries. But individuals who dare to read the whole investigation report (as I did) will realize that it doesn’t actually offer a justification for the massive trade actions launched by Mr. Trump against China. The report itself recommends other avenues that, in light of the evidence, were warranted.

Now again, having said all that: yes, certain Chinese practices have raised concerns. So now the important question becomes: how do we address these concerns most effectively? First, we have to carefully distinguish between political rhetoric and economic analysis when it comes to the localized effects of Chinese competition within the United States. Yes, as we would expect, some companies, some workers, some communities did get hit hard by China’s increased presence in certain sectors. And you probably could find something similar for almost every other country. When you open up markets, you increase competition. This shifts the patterns of production and of trade, and of course leads to localized effects. So then the questions you need to ask become: how do these (sometimes harmful) local consequences measure up to other localized and general effects elsewhere in the economy? What can we say about how Chinese presence and Chinese competition affect consumption, production, and innovation across the United States? We need to address all of those complex developments. We can’t just have political leaders blaming somebody else for certain localized negative effects — while never even mentioning the rest of the story.

Politicians (and I say this as a former politician) find it very useful to blame others for those negative effects, and to deflect responsibility for not addressing them. When you have a political system that doesn’t care about certain communities who have struggled with poverty for generations, that doesn’t care about its strikingly poor educational results, that spends enormous sums on healthcare but still doesn’t provide universal coverage, that reforms its tax system by making this even more regressive — then you need somebody else to blame for these painful conditions.

It is easy to say: “Okay, you know how income distribution has worsened in the US, with the median wage not increasing in 50 years? That’s China’s fault.” Or maybe four decades ago, you could say: “That’s Japan’s fault.” But our work as researchers or economists is to say: “Wait a minute. You have failed to implement policies to address these issues that should have been of very serious concern. Don’t blame the Chinese or the Mexicans or the Europeans or globalization.” What you need is a system in which, in the presence of rapid technological progress and globalization, your social policies help to generate benefits and opportunities for the general population, not just for a few individuals. If you have taken the political decision not to care for large segments of your population, let’s be transparent about that decision, rather than blaming others for the consequences.

BH: Just picking up on Ernesto’s points, the political debate ignores the fact that the share of manufacturing employment in the US has been declining steadily over the past 50 years. If you plot this on a graph you see a pretty straight downward-sloping line. The effect of China’s reintegration (a big shock, as discussed by Alan Winters in his chapter) is not very noticeable on such a graph. If you were to ask, “Okay, so where does China enter into this decline?” you would only see a small blip. This doesn’t mean that competition from China and from other emerging economies in recent decades has not caused real pain for many communities. But in the bigger scheme of things, the case for China causing a dramatic decline in American manufacturing employment is not as strong as often made out to be. This is a long-term trend.

Also if you compared US statistics to trends in a manufacturing powerhouse like Germany, you wouldn’t see that same decline in manufacturing employment. Manufacturing productivity has risen a lot, but the labor share in manufacturing has remained more stable than in the US — in part because of complementary policies ensuring that a lot of the higher-skilled economic activity, as well as a lot of the mid-skilled activity, has stayed in Germany.

The service sector’s role as a creator of jobs also needs to be considered. Over time there has been a big shift into services, activities in which the United States has a comparative advantage, reflected in a surplus trade balance in services. Net overall unemployment in the US has remained relatively low. So when we only focus on the manufacturing sector, we lose sight of the bigger picture, with its trends towards structural transformation of the economy, towards services-related economic activities — many of which remain less tradable than goods. Managing adjustment costs for those negatively affected is really where the US lags behind.

Then for another mystery of recent US trade policy, how might our unilateralist approach to addressing what we deem problematic Chinese behavior crystallize the strategic mysteries of neglecting to use effective multilateral tools that we ourselves played a significant role in establishing? And how could the US most constructively fortify international trade norms by directing its complaints against China through proper institutional channels?

EZ: There’s not a silver bullet. First the US should recognize that a functional multilateral system remains in its own best interests, as it has ever since the Second World War’s end. The peak of US global power actually happened back then, with Europe and Japan devastated, with the Soviet Union (we at least now realize) economically very weak. The US was then producing 50 percent of global GDP, and had emerged as a great military power. The US played an essential role in shaping the postwar rules-based international system — and the most astute US leaders understood that this system would also constrain US exercise of its own power.

Today, from this balance-of-power perspective, some are concerned about the rise of China. If you worry about China becoming an overwhelmingly powerful country, isn’t it in your interest to agree with China and other large players that there should be strengthened rules of engagement, participation, decision, and enforcement on many issues?

The US still has great might and influence, although with eroded leadership and moral authority — thanks not only to Trump, but also to the Middle East interventions and the Iraq War and other events. The US still has the leverage and the self-interest to exert a decisive influence on the re-powerment of international institutions. It would be in the interest of China (and certainly the European Union, Japan, and additional emerging powers like India and Brazil) to work toward that goal, if they really care about the long term. The US also has very important long-term interests at stake (for its own domestic politics, too) in showing that it can act constructively and get something concrete out of China, and move along a more positive track.

This poses tremendous domestic political problems, but I think there are avenues to solve them. For example, the new US administration should recover the Bilateral Investment Treaty practically concluded between the Obama administration and the Chinese government (and begun, by the way, by George W. Bush’s administration), possibly reinforcing this treaty in the most important disciplines, as well as in market and investment access. A good deal put before the American public and the US Congress would prove far superior to the nonsense trade war of the last two years. This new agreement should be and conceivably could be even better than the bilateral investment agreement recently announced between the EU and China — which, frankly, came as a surprise, notwithstanding the long time it took to negotiate.

I remember a conversation in which my friend Javier Solana said: “You know, this American anti-China craziness is infecting Europe, and increasing by the day.” So now I can only hope to be pleasantly surprised by the Biden administration, also, figuring out how to make an effective case to the public on much better ways to respond to Chinese economic competition. That would be a huge accomplishment.

So here with the mysteries of America’s recent China policy still in mind, and with a new presidential administration taking office, what do you consider the most significant longer-term losses that the US brought on itself by abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership — which in your account had offered the promise of liberalized, stabilizing, mutually beneficial trade with an impressively heterogeneous range of countries? And which of those losses could a new administration now make up for through what kinds of course corrections or updated initiatives?

BH: To connect this back to the WTO, Biden has explicitly said that trade agreements won’t be front and center for his administration anytime soon. Partly because of the domestic politics, partly because they have much more pressing concerns, the Biden administration will need to put its attention elsewhere. But that also means there may be more time for the WTO membership to consider reforms that facilitate plurilateral engagement — among groups of countries discussing, negotiating, and agreeing on rules for particular issues they share. Plurilateral approaches that focus on specific trade arrangements offer, for example, an opportunity to pursue elements of what was addressed in the post-TPP Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (especially on the regulatory side), and to say: “There’s no need to negotiate a traditional discriminatory trade agreement. We can pursue cooperation on an open plurilateral basis, without having to negotiate a complicated package deal spanning all of the topics that one finds in a typical trade agreement.”

Insofar as we worry about state-owned enterprises, competition policy, services regulation, cross-border data flows, digital-economy policies (to name some of the high-profile policy areas), the WTO offers a way to start thinking about negotiating plurilateral agreements. Asia Pacific countries, including CPTPP signatories, have taken the lead on this approach right now. New Zealand, Singapore, and Chile have negotiated, for example, digital-economy partnership agreements, which essentially set the rules of the game for data regulation, data flows, and data privacy. These types of initiatives don’t require a trade agreement, but they can appeal to businesses in the US, while at the same time ensuring that concerns of consumers and regulators are addressed. They don’t bring all the political baggage associated with large trade agreements like the TPP — which clearly would have brought direct benefits to a large swathe of US industries. So emphasizing these plurilateral arrangements could offer one way for the Biden administration to at least start moving forward on trade.

For one other point of focus, I believe that more energetic US engagement in the ongoing discussions taking place in Geneva would benefit the entire WTO. Currently the US only participates in some of these ongoing discussions. It really should participate in all of them. Putting on the table additional topics important to the US, but also to many other WTO members (like subsidies), could help increase the salience of the WTO as a tool to assist countries in dealing with trade tensions. Today, insofar as we have international discussions on issues like industrial subsidies, these tend to happen outside the WTO. They should be brought to the WTO, and should include a broader range of like-minded nations.

EZ: Bernard’s making another very important and very astute point. He and I share the idea that this new Biden administration will have limited political capital on trade topics, and should apply it carefully. Alleviating tensions with China of course stands out. If these tensions don’t get addressed, that confrontation will complicate every crucial aspect of our multilateral system. So I would say: decrease the tensions with China (which seems doable), and then apply your capital in the multilateral system.

Let me add, just as a side note, that I didn’t like the TPP enormously — because it served the US interest so well, and not so much that of several other participants, including my own country, Mexico. The Obama administration worked very skillfully and got the best deal for the US, which makes the mystery of Trump abandoning it even greater. I don’t think Mr. Trump dared to read a half-page serious briefing on the TPP. He’d made his decision, no matter what, well before. On his administration’s third day, he just killed it without providing any sound reasons. Economic and political historians will study this for decades, as an extreme example of folly. This trade instrument, clearly advantageous for the US, and started by a Republican administration, was discarded without explanation, seemingly because Donald Trump associated it with Barack Obama.

Finally then, to return once more to this book’s introduction, and to its perhaps most pointed challenge “to identify and implement policies that promote economic development in a world of global value chain-based production, e-commerce, and digitization where small firms can become micro-multinationals by using electronic platforms and exploiting mobile information and communications technologies,” could you offer some examples of what most pressing struggles such firms face — and of which kinds of policies, at which national/international levels, will help them most?

BH: That definitely depends on which countries we discuss. But some of the biggest challenges firms face right now come, as we mentioned, from regulatory regimes. In a world where you connect digitally with customers all across the globe, where you source intangible inputs over the Internet, where you provide services and then need to get paid, negotiating all of the different regulatory regimes can create a big barrier. We see very clearly in the EU, for example, an increasing focus on consumer protection, on data privacy, on know-your-customer requirements — with none of these regulations intended to discriminate, but with many of them difficult for small firms based outside the EU to satisfy. Their home country might not meet EU standards for data protection, for example. That might mean they simply cannot pursue business opportunities.

Today much of this agenda gets discussed in the WTO under the headings of e-commerce or of domestic regulation of services, both of which are critically important for countless small firms. Many developing countries don’t even participate in these talks, which is very unfortunate. The end result may be increasing exclusion for firms in the relevant countries, partly because these companies’ home governments are not focusing on the potential implications and benefits of engaging on this very important agenda.

EZ: I’d add that, one consequence of the way global value chains have evolved over the past 40 years is that firms in many countries can now be part of value-added activities — which was not the case in the old vertically and horizontally integrated industrialization. Not only in China, but in many other countries, suppliers now might serve literally thousands of customers, in dozens of countries. That all gets integrated like never before into what the whole world produces and consumes.

However, we’ve seen now this new protectionism arising behind the borders, with extreme actions like those taken by the US vis-à-vis China. Through uncertainties in the global rules, or through abuse of those rules, we will inhibit these new participants from entering the global market. I find that very very unfortunate. I’d call it unfair — because again, the big players will survive and even thrive under these arrangements, but all at the expense of diminishing opportunities in less-developed economies. That’s really why we insist on these clearer and stronger disciplines, so that everybody knows the rules of the game, and so the most important decisions don’t just get made according to the will and the might of one or two countries.