A. Introduction

Jurisprudence in Germany is traditionally conceived as a hermeneutic science that rarely uses empirical, letalone quantitative methods. Footnote 1 It focuses on individual texts—particularly statutes, regulations, and court decisions—which are subject to “close reading” to answer research questions. Insofar as one might consider court decisions as empirical evidence of the application of a statute, it is often not possible to look at all relevant decisions. Instead, the researcher will have to limit their research to a subset that is not necessarily based on a random sample. The researcher’s choice of material may be restricted by the availability of the material, Footnote 2 or it may follow considerations of importance arrived at by other researchers or practice. Footnote 3

A legal researcher may be interested in determining which of various interpretations of a legal norm is being supported by a majority of courts. Exact counting, however, traditionally plays a less significant role. As far as the interpretation of statutes is concerned, an argument’s—perceived—persuasiveness is considered to be relevant, not its frequency. However, studies employing quantitative methods to reach more empirically substantiated conclusions about courts’ behavior appear to have become more popular in recent years. Footnote 4 These are usually based on a manual classification of the relevant phenomena carried out by legal scholars. Provided that intersubjectively comprehensible guidelines for annotation exist, this may ensure that the counted phenomena can withstand assessment by other experts. Manual coding, however, is expensive in terms of personnel and time, and may again result in a limitation of documents that can be considered in the study. These barriers call for the supportive use of computer-assisted methods.

These computer-assisted methods include the automated search for keywords or text passages that follow more complex rules and machine-learning algorithms based on statistical calculations. The term data mining Footnote 5 or, more specifically, text mining subsumes various procedures for analyzing data and text, which may, in principle, be applied to help answer research questions in legal studies. Their application without a clear starting hypothesis, however, harbors the risk of arbitrary retrospective interpretation. Footnote 6 Furthermore, a text mining algorithm’s way of decision-making may not be entirely comprehensible for human experts, which may impair the intersubjective communication of results.

In this article, we introduce a possible method for analyzing a larger corpus of court decisions by using a text mining procedure as a preparatory step and having its results evaluated by legal experts before using them to answer specific research questions. In doing so, we analyze the thematic composition of about 3,300 decisions by the German Federal Constitutional Court that result from the two most frequent types of proceedings—the constitutional complaint and the referral for judicial review—and have been published in the Official Report Series. Footnote 7 The data is published as a corpus and publicly available. Footnote 8

To begin, we will give a short introduction to text mining and specifically, topic modeling and its previous application in legal research in section B. Then, after an introduction into German Constitutional Procedure and its most frequent types of proceedings, which inspired our hypotheses, we will embark on a topic-modeling-assisted inquiry into the subject matters characterizing constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review in section C. The article finishes with a conclusion in section D.

B. Topic Modeling and its Application to Legal Research

Text mining can use machine learning methods that may either be supervised or unsupervised. Footnote 9 Supervised methods require training data in the form of manually labeled data. If, for example, the text is sorted into fixed categories, which is referred to as classification, these categories have to be decided on and related to a certain amount of data points to train a classifier that may then classify new, unseen text. Alternatively, unsupervised methods do not require human decisions on categories and can use information inherent in the texts to assign them to one of several clusters, which is referred to as clustering. Topic modeling is an example of an unsupervised method.

I. Topic Modeling

Topic modeling algorithms are statistical text mining or information retrieval methods used for uncovering the main themes underlying a collection of documents, their connection to each other, and their development over time. Footnote 10 Different models and algorithms exist. Currently, the most widely used model is Latent DirichletAllocation (LDA). Footnote 11 LDA is built on the presumption that all documents in the collection share the same original set of topics, but each document may concern these topics in different proportions. Footnote 12 Therefore, only a selection of these topics will appear in the document. A topic is defined as a “distribution over a fixed vocabulary.” Footnote 13 Each word in the vocabulary for a given topic is assigned a probability of appearing in a document about this topic, where probabilities sum up to one for each topic. Footnote 14 Topics are assumed to be static and fixed before any document is written. This means that topics cannot evolve to contain new words in later texts—such as would be expected of historical progress, where for example, the present-day discourse around the European Union will contain different words compared to the European Coal and Steel Community— and topics cannot merge or split over time either.

The creation process for each document is assumed to consist of two steps. Footnote 15 First, a distribution over topics is randomly chosen. In other words, the topics about which the document is written and the proportions of the document reserved for these topics are determined. Second, for each word in the document, a topic from said distribution is randomly chosen, and the word itself is randomly selected from the distribution of the vocabulary corresponding to this topic. It follows that the order of words is not considered important. In reality, of course, documents are not created in a random process.

Topic models aim to discover these “hidden structures,” which are the topics underlying the whole corpus, the individual documents, and the weights of words within a certain topic. The model randomly assigns words to topics and topics to documents, then shuffles them until a maximization condition is met. Footnote 16 In general, no annotations or metadata are required, although some topic models may take metadata such as authors of documents or timestamps Footnote 17 into account. Footnote 18 Document preprocessing includes removing stop words and other words that appear too frequently in the corpus to provide semantic information. Footnote 19 Rare words are also typically excluded, both because they cannot be usefully allocated by frequency and to lower computational cost. Footnote 20 Furthermore, documents may be shuffled. Footnote 21

II. Application to Legal Research

The result of this process is a list of topics which can be used as a classifier of documents by topic and may provide a basis for further corpus exploration. Footnote 22 More generally, topic models can assist in quantitatively examining the semantic features of legal corpora. Footnote 23 Legal studies involving topic models usually report the list of topics identified by the algorithm and labeled by lawyers. While some focus on the technical aspects of the process, Footnote 24 others use the results for more specific research questions. For example, David Law examines 171 preambles of constitutions and international human rights instruments to find evidence of “constitutional archetypes” underlying these documents. Footnote 25 Assuming a “liberalist,” a “statist,” and a “universalist” archetype, the author generates models of three, four, and ten topics and considers the three-topic-model to best fit the corpus, whereas in a four-topic-model, the “universalist” archetype is represented by two topics. Footnote 26 While both the “liberalist” and the “statist” topics appear to be connected with characteristic vocabulary, this does not seem to be the case for the “universalist” archetype. The author further examines correlations between the predominant archetype of a constitution and variables such as its origin—whether it is a “newer” state or human rights instrument— the legal system—whether it is civil law, common law, or authoritarian— and characteristics of a fundamental rights catalog. Footnote 27

In their study of United States Supreme Court decisions, Livermore, Riddell, and Rockmore used topic modeling to compare the distribution of one hundred topics in Supreme Court opinions with those in Appellate Court opinions. Furthermore, they examine which topics are correlated with the grant of certiorari and whether differences in semantic content are changing over time. Footnote 28 The authors show that topic distributions of Supreme Court decisions and the corresponding Appellate Court decisions are more similar than those of Supreme Court decisions and 10,000 randomly chosen Appellate Court decisions. Footnote 29 They conclude that Supreme Court opinions are measurably distinct compared to Appellate Court decisions, that a correlation between topic proportions and the likelihood of a grant of certiorari exists, and that Supreme Court opinions become more distinctive over time when measured against federal appellate cases. Footnote 30

In a study of the issue content of European Court of Justice (ECJ) decisions, Dyèvre and Lampach create separate models for infringement and annulment rulings—assuming fifteen topics—and preliminary references—twenty-five topics Footnote 31 —and visualize the resulting topics as networks. An examination of the development of topics over time provides results that are evaluated to be “in line with the dominant narratives of the European integration process in EU studies,” Footnote 32 such as a decline of “constitutional” topics in preliminary reference documents. Issue attention in infringement cases is considered to vary less than in annulment or referral cases. Footnote 33 To validate their topic model, the authors relate it to a citation network of manually collected decisions on family reunion cases and conclude that higher centrality in the citation network correlates with higher topic proportion. Footnote 34

Carter and Rahmani use topic modeling to track the development of two specific legal doctrines in judgments of the High Court of Australia. The authors create models consisting of ten and twenty topics and visualize the topic weights in a number of judgments related to the doctrines in question—and selected in accordance with traditional legal methods—to analyze the evolution of topic content in these cases. Footnote 35 Furthermore, they show the positions of the selected judgments in a network of the dominant topics of all judgments in the corpus. Footnote 36

In the context of German law, recent work by Gumpp and Schneider creates a topic model of the entire German statutory law consisting of thirty topics, employs network analysis to visualize stronger and weaker connections between the statutes belonging to a certain area of law, and discusses possible uses of topic modeling for research on the system of legal principles, sources of inspiration for analogous application of laws, and guiding principles for potential codifications of areas of law. Footnote 37

III. Challenges

This short introduction to topic modeling and its application to legal research questions has already hinted at some of the methodological challenges involved with this approach:

The assumption that documents are a “bag of words” in which the order of words does not matter is unrealistic. Footnote 38 Also unrealistic is the assumption that the order of the documents in the corpus is irrelevant. It may be contested whether topics are truly static, particularly if the corpus spans several decades. Footnote 39 Adaptations of LDA have been developed to resolve these issues. Footnote 40 Documents may be randomly shuffled to avoid a bias towards earlier cases. Footnote 41 This does not, however, resolve the fundamental problem that probabilities—and thus statistics over word distributions—must be doubted on a conceptual level. Over time, new words are coined, which changes the relative frequency of all words to appear in the corpus, and new discourses develop, which bring with them a terminology that is more diverse at the beginning before they are subject to a certain degree of standardization. Footnote 42

Composition and preprocessing of the corpus or various subcorpora are, of course, areas for dispute that should be resolved with the research question in mind. Furthermore, some court-specific words do not serve the purpose of distinguishing between documents because they occur too frequently. Footnote 43 Excluding these words should prevent topics that consist of words like judgment, statute, law, or the name of the court—words that, at first sight, can appear in any document and are not distinctive of a particular topic. However, in contrast to language-specific stop words that will be frequent in any corpus, court-specific words might, in fact, be more frequent in some documents than in others and thus, might indeed characterize a topic. Footnote 44

The number of topics is determined by the researcher’s choice or algorithmically through statistical preprocessing. The assumption that this number is known and fixed is unrealistic. Law assumed three constitutional archetypes and concluded that this number leads to more convincing topic compositions than four or ten topics. Footnote 45 Due to the non-deterministic algorithm, however, this result might be different in a new calculation. In other research setups, the number of topics may vary between different time periods and depend on the changing amount of cases and the broadening area of competence of the courts. Footnote 46 For their choice of topic numbers, Dyevre and Lampach relied on the interpretability of the topics and the number of documents in their subcorpora, which resulted in different amounts of topics for different types of procedures. Footnote 47 The unsupervised topic modeling algorithm has no sense of what a meaningful topic is and is given no definition. Footnote 48 Setting the number of topics too low may result in topics that are too general and appear throughout the corpus, whereas setting it too high may lead to “topics lacking enough contextual markers to provide a clear sense of how the topic is being expressed in the text.” Footnote 49

Consequently, Carter and Rahmani find that their twenty-topic model is marked by greater granularity than the model for ten topics. Footnote 50 This may lead to topics that are less interpretable and therefore, less useful for humans. Footnote 51 To avoid having to guess a number of topics, one may apply algorithms which automatically determine the number of topics. Footnote 52 While this yields statistically better partitions, the interface to linguistics is entirely undefined because no linguistically motivated, scalar, and quantitative model of what constitutes a topic exists. This includes the lack of definition as to which quantitative markers, such as specifiable frequencies of word co-occurrence, would clearly demarcate topic boundaries. Thus, even the best statistical model cannot be shown to correspond to an ideal linguistic model of a topic. Footnote 53 This is further implied in the statement that the choice between a higher and a lower number of topics yields topics of varying granularity. While there may exist subcategories of meaningful granularity, at present, there are no best practices to decide whether a chosen number of topics adequately represents subject-specific topics of interest.

Furthermore, researchers must decide which topic model to use depending on the data and the research questions. Footnote 54 While Latent Dirichlet Allocation is common, other algorithms also exist. Footnote 55 When interpreting the results, it should be taken into account that Latent Dirichlet Allocation is not deterministic. Running the same algorithm on the same corpus repeatedly may lead to different results depending on the starting point of the algorithm—word or document. This contradicts the idea of an “ideal” model and escapes validation through sampling due to the staggering number of possibilities—the varying number of plausible topic numbers multiplied by the number of seeds, that is, points of initialization of the algorithm.

Finally, the interpretability and coherence of the resulting topics may be questioned. Footnote 56 Providing a label may not capture every dimension of the topic itself. Footnote 57 While studies often report that labels are intuitively interpretable and match traditional legal categories, Footnote 58 there are approaches to empirically validate the coherence and interpretability. Examples include classifying documents based on topic proportions, using labels provided by human readers as categories, Footnote 59 comparing the topic model to a citation network of manually collected decisions, Footnote 60 and having human subjects evaluate the coherence of the most probable words for each topic. Footnote 61 In a non-legal context, Chang etal. conducted large-scale experiments on how humans interpret the semantic coherence of topics and their representation in documents for three different models. Footnote 62 In order to evaluate topic coherence, the test subjects were presented with six words, of which five were the most probable words from a randomly chosen topic and the sixth was a randomly chosen word with a low probability in that topic but a high probability in some other topic. Footnote 63 Whether the models’ assignments of topics to documents are consistent with human judgments was measured by presenting the title, a snippet from a document, four topics associated with this document, and one topic chosen randomly from the remaining topics. Footnote 64 The authors conclude that “humans appreciate the semantic coherence of topics and can associate the same documents with a topic that a topic model does,” while traditional metrics for topic evaluation do not capture whether topics are coherent or not. Footnote 65

Despite these uncertainties, topic modeling is widely used, and because of the growing availability of large datasets it is likely to become more widely used in the social sciences. Leaving some of these aspects unaddressed, we will present results from a topic model based on a corpus of FCC decisions and then provide an example of how topic modeling can be used as a preprocessing tool in a computer-assisted hermeneutic approach to the hypothesis-based analysis of large text data.

IV. A Topic Model of the FCC’s Official Report Series

When applying topic modeling to legal corpora, an obvious approach is choosing several topics, reporting the word clusters generated by the topic modeling algorithm, and labeling them according to traditional doctrinal ideas of areas of law or subjects of legal disputes. Recognizable patterns are easily found. We generated a topic model of the decisions published in the official report series of the FCC between 1951 and 2017. In order to avoid bias when interpreting the list of topics, we used a written catalog of questions to ask a small number of colleagues, who are all familiar with the FCC’s decisions, about what topics they expect to appear and how these topics will develop over time. The answers were hardly comparable, which shows that the concept of what constitutes a topic is by no means unambiguous. Some common ideas, however, emerged: inter alia topics concerning Europe, equality—both general Footnote 66 and gender-equality Footnote 67 —religion, freedom of expression, technology and data protection/privacy rights, and democracy were expected as well as a rise in prevalence of the topics Europe, equality and technology/data protection.

Our corpus of Federal Constitutional Court decisions comprises 9,267 decisions published between 1951 and 2017. For this analysis, we only use decisions published in the official report series, 3308. A number of court-specific words and some linguistic artifacts were removed. Footnote 68

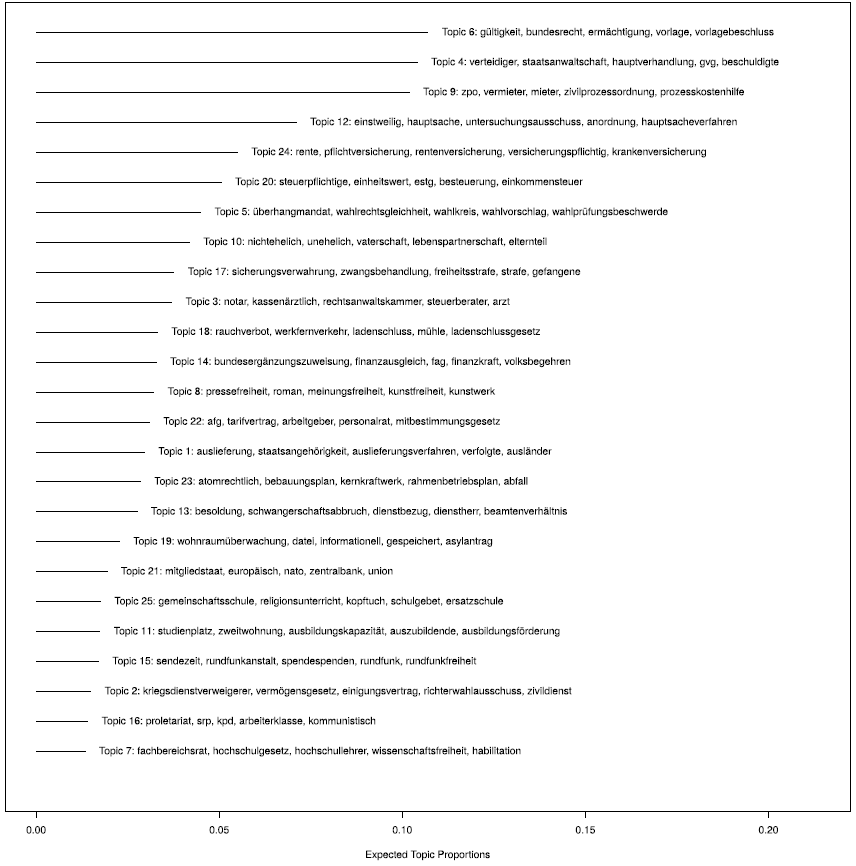

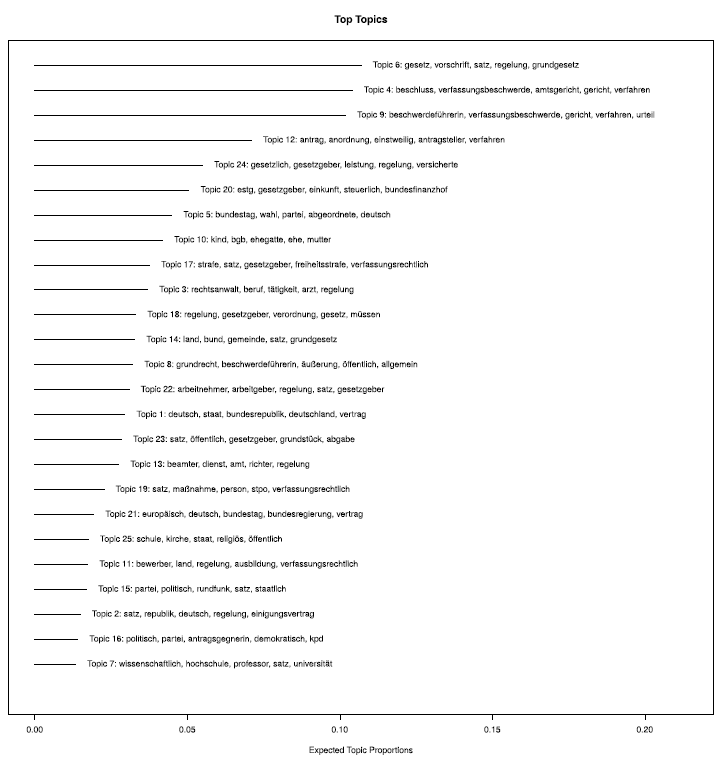

In what follows in this section, we used the stm package in R with the number of topics set to twenty-five. Footnote 69 The distribution of topics is deterministic in this case because the initialization of the model was based on Arora, Ge, and Moitra’s spectral algorithm. Footnote 70 The results are shown in Figure 1—displayed are the five most frequent and exclusive words, that is to say, words that occur in only one topic, reported as frex—and Figure 2—five most frequent words which may overlap between topics, reported as freq. All words are set to lowercase in the analysis and will be reported as such.

Figure 1. A topic model of the official report series for 25 topics—frequent and exclusive, frex.

Figure 2. A topic model of the official report series for 25 topics—most frequent words, freq.

We find that when representing topics by the five most frequent words, topics more often seem to be made up of general words that may appear in different contexts in an FCC decision. The frex words give more specific hints. Nevertheless, in some cases looking at the frequent words in addition to the frex words can help with interpreting the topic content.

We find topics associated with

-

Europe: topic 21 (frex: member state, european, central bank – freq: german, treaty),

-

religion: topic 25 (frex: religious education, school prayer, head scarf – freq: church, religious),

-

freedom of expression: topic 8 (frex: press freedom, novel, freedom of expression, freedom of artistic expression, work of art – freq: expression, public, general),

-

technology/data protection: topic 19, (frex: surveillance of the home, file, informational, stored – freq: stpo Footnote 71 ).

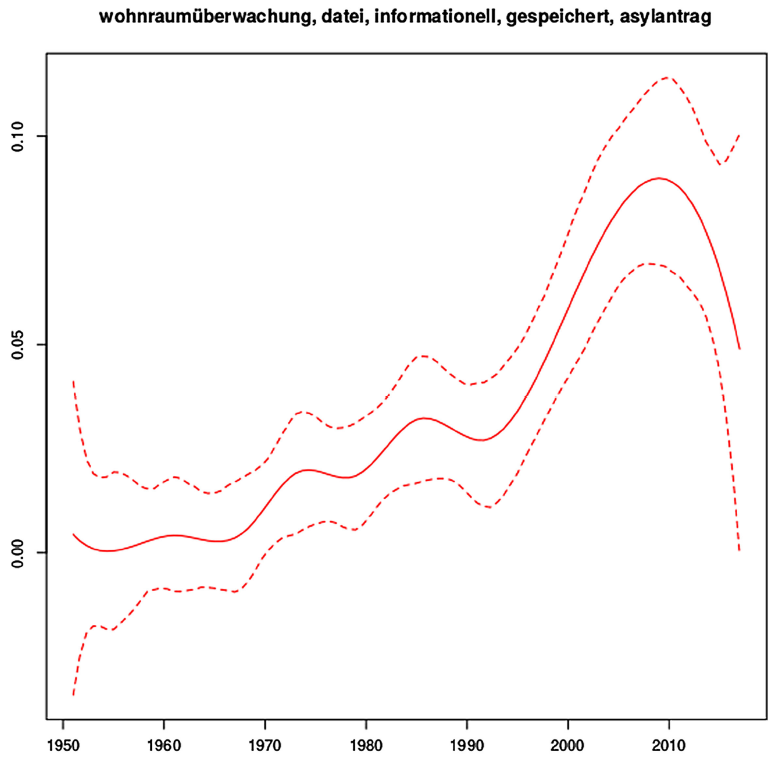

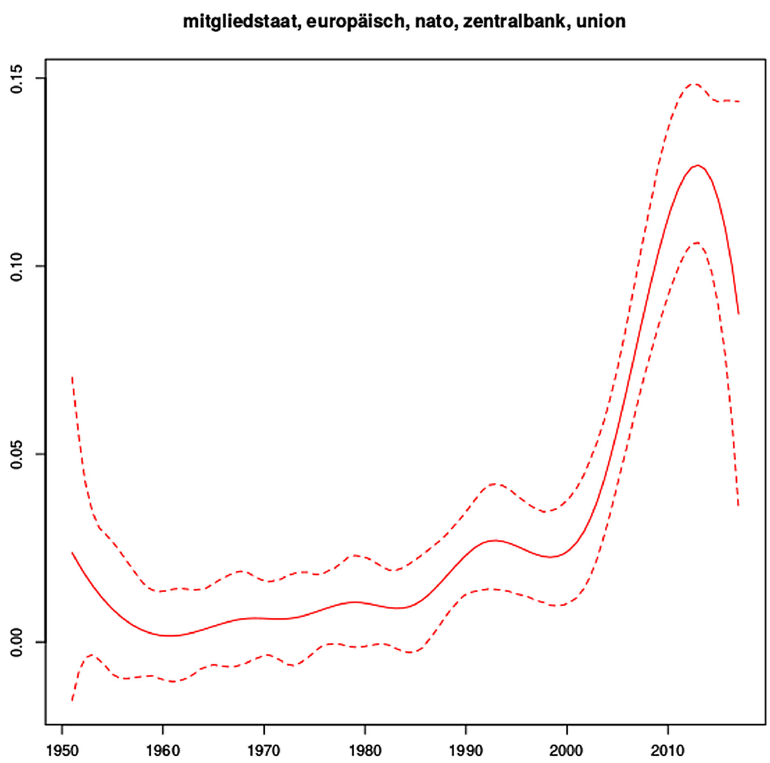

As expected, topic prevalence for topic 19 (data protection) and topic 21 (Europe) increases over time in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Development of topic 19, data protection, over time.

Figure 4. Development of topic 21, Europe, over time.

There is no topic obviously concerned with democracy, although some aspects of the principle of democracy may be represented in topic 5, which seems to relate to elections—frex: Overhang mandate, electoral equality, constituency, and electoral complaint—freq: Bundestag, election, party, and deputy—and possibly topic 15, which might relate to political parties’ right to be equally represented in broadcast—frex: Broadcasting time and freedom of broadcasting—freq: Political party, political, broadcast, and public. Likewise, it is difficult to find an equality or gender equality topic. Questions of equal treatment, however, may concern a wide range of subject matters, such as, apart from the aforementioned electoral equality, family law, which is represented by topic 10—frex: Illegitimate, paternity, civil partnership, parent—freq: Child, spouse, marriage, mother—or tax law, with which topic 20 is concerned—frex: Taxable person, ratable value, estg, Footnote 72 taxation, income tax—freq: income, fiscal.

While the most frequent topic, topic 6, contains words of a more general character, the second-most frequent topic, topic 4, seems to be related to the criminal procedure—defense counsel, public prosecution office, main hearing, and accused person. Footnote 73 Words related to the enforcement of the sentence—frex: Preventive detention, coercive treatment, imprisonment, punishment, and prisoner—seem to cluster in topic 17. For technical reasons, fourteen documents had been missing in this initial exploration. They have been included in a new model, which can be found in Appendix Section I.1. This second model, although based on almost the same data, provided remarkably different results. The proportions, order—in terms of proportionality—as well as the composition of the topics are different. In the new model, when looking at the five most frequent and exclusive words, topic 19 appears to deal with data protection—surveillance of the home, privacy of telecommunications, Federal Intelligence Service—however, it appears to be interwoven more strongly with criminal law—preventive detention, prisoner—than in the first model where more general words such as file, informational, and stored appear among the five most frequent and exclusive words. Indeed, when taking the five most frequent words into account, topic 19 appears to be mainly relating to criminal law. Furthermore, while in the first model the five most frequent words in topic 16 appeared to relate to communism and thus, possibly, to the decision which banned the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), Footnote 74 no such topic can be found in the new models. This exemplifies that automatically generated topic models can react sensitively to minor changes in the data.

Our corpus exploration has shown the difficulties in defining what constitutes a topic and in interpreting a computer-generated topic structure. Therefore, we intend to use topic modeling only as a first step in order to define topic terms we are interested in.

C. Comparing Areas of Law in Different Types of Proceedings

In this Section, we will investigate the areas of law represented in constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review. We will give an overview of the different types of proceedings in German constitutional procedure in Section I, which is the foundation for our hypotheses discussed in Section II. Afterwards, we will explain our research methods in Section III and present the results in Section IV, before undertaking a follow-up investigation into sub-areas of private law in Section V.

I. German Constitutional Procedure

The German Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) does not form part of the regular court system in Germany. In contrast to the Supreme Court of the United States, its jurisdiction is strictly limited to matters of constitutional law. Accordingly, legal remedies to the FCC are restricted to a numerus clausus of types of proceedings. These proceedings differ, inter alia, concerning the initiating party and the scope of protection. Furthermore, they involve differing prerequisites, for example, prior review by ordinary courts or time limits for commencing proceedings. We will analyze only two types of proceedings: constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review. This is motivated primarily by the fact that both constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review may concern an equally wide range of questions of constitutional law—for reasons that will be outlined below—while other types of proceedings often pertain to specific constitutional provisions, such as electoral rights in electoral complaints, separation of powers in Organstreit proceedings, or the prohibition of political parties. Consequently, it is expected that the subcorpora of these latter types of proceedings will be primarily concerned with these specific legal issues. The second, more practical, reason for limiting our analysis to only two types of proceedings is the representation of the different proceedings in the corpus. While not all decisions on constitutional complaints have been published, Footnote 75 they nevertheless dominate the official report series: fifty-eight percent of the 3,308 decisions published in the official report series concerned constitutional complaints. Referrals for judicial review of statutory law are the second most common type of proceeding before the FCC. They account for twenty-five percent of the cases in our corpus. In addition, there are sixty-six cases in which constitutional complaints and referral for judicial review have been joined, which is about two percent.

1. Constitutional Complaints

Constitutional complaints Footnote 76 can be initiated by any natural or legal entity that claims a violation of their fundamental rights. Strict procedural prerequisites counterbalance the large number of potential complainants. Generally speaking, a constitutional complaint will only be heard after legal protection has been refused by the ordinary courts. A complainant must demonstrate that they have exhausted any regular legal remedy before filing a constitutional complaint. Accordingly, constitutional complaints are usually directed against the final decision of a regular court, which, according to the complainant, is in breach of the Constitution—Urteilsverfassungsbeschwerde. Here, the complainant will regularly base their complaint on one of the following arguments. Either they will argue that the last-instance regular court violated their fundamental rights by applying a law in an unconstitutional way, for example, by misbalancing the affected constitutional interests. Conversely, they may claim that the statutory law itself that governs their case may be unconstitutional. In this latter case, the complainant formally directs their complaint against a court decision but indirectly accuses Parliament of an unconstitutional act. Thus, the FCC will indirectly control the constitutionality of statutory law, and, as a consequence, it may invalidate such a law when it finds its provisions to be in violation of the Constitution. Footnote 77

Under specific and exceptional conditions, the FCC does hear cases that directly target statutory law, Rechtssatzverfassungsbeschwerde, and in which the complainant is not obliged to first seek legal protection from the regular courts. These cases include complaints against the statutory authorization of clandestine measures that typically go unnoticed, Footnote 78 for example, secret surveillance by police authorities, as well as provisions concerning fines or punishments. Footnote 79 The constitutional complaint can only be lodged within one month after the last-instance court decision, Urteilsverfassungsbeschwerde, or a year after the promulgation of the challenged law, Rechtssatzverfassungsbeschwerde. Footnote 80

Thus, it appears that the FCC is easily accessible by way of constitutional complaints. A large number of complaints is, however, filtered by the Court’s relatively harsh admissibility tests. Footnote 81 Notably, complainants must sufficiently substantiate their complaints in order to be heard before the FCC. This threshold can actively be used by the Court to limit its caseload as it provides the justices with certain procedural leeway when assessing a complaint. Footnote 82 Moreover, about ninety-nine percent of constitutional complaints have lately been referred to chambers of three rather than the full senate of eight justices. Footnote 83 Because chamber decisions have only been systematically published since 1998, we restrict our investigation to those decisions that have been published in the Official Report Series. Footnote 84

2. Referrals for Judicial Review

Referrals for judicial review Footnote 85 can be initiated by any court. Consequently, the group of possible initiators, although smaller than in the case of constitutional complaints, is still large compared to other types of proceedings. Whenever a court is convinced of the unconstitutionality of statutory law or the incompatibility of state law with federal law, which is relevant to a specific case on its docket, it is obliged to suspend the proceedings and ask for a preliminary ruling by the FCC. Thus, referrals for judicial review regularly occur at an earlier stage than the constitutional complaint because constitutional complaints may, for the most part, only be filed after exhausting all regular legal remedies. In contrast, referrals for judicial review take place as an extraordinary intermediate step during regular proceedings. As a prerequisite, the law in question must have been enacted after the Basic Law entered into force in 1949. Footnote 86 This is because Article 100 (1) of the Basic Law intends to protect the legislation passed by the democratic legislator, however, courts may disregard unconstitutional laws predating the Basic Law because in such cases, no protection is necessary. As opposed to constitutional complaints, referrals for judicial review are not subject to any time limits.

Similar to the constitutional complaints, the FCC has established strict requirements for the admissibility of referrals for judicial review, particularly concerning the interpretation of the requirement that the regular court’s decision depends on the validity of the law. The referring court must substantiate its reasons to refer the law to the FCC in a comprehensible way, Footnote 87 and these reasons must not be “manifestly untenable.” Footnote 88 These requirements provide the FCC, to some extent, with a rather flexible instrument to control its caseload Footnote 89 and possibly the choice of subject matter. Footnote 90 A decision notably does not depend on the validity of the law if the law can be interpreted or developed in a way that is in compliance with the constitution. Footnote 91 In practice, half of the referrals are considered to be inadmissible. Footnote 92

II. Hypotheses

In light of the abovementioned, should we expect notable differences in topic prevalence between the two types of proceedings? On a purely conceptual level, the coverage of issues should be nearly identical. In both types of proceedings, admissibility criteria allow the FCC a certain level of flexibility in accepting cases. If the case is admissible, the FCC performs a full-fledged fundamental rights analysis. Footnote 93 This includes questions of a mere formal constitutionality of statutory law—for example, federal compared to state competencies and observance of the legislative process—in both proceedings. Footnote 94 Therefore, the applicable constitutional law is basically the same in both types of proceedings. Footnote 95

Nevertheless, we expect significant empirical deviations between the thematical issues covered by both types of proceedings. Apart from seeing topics that concern the different procedural requirements of both proceedings, we expect a clear overrepresentation of issues concerning social law, tax law, and civil service law in decisions on referrals for judicial review. Conversely, we expect cases that deal with free speech, the general personality right, data protection, EU Law, and criminal and private law to mostly occur in constitutional complaints.

The reasons for our expectations are twofold. They include considerations as to the asynchronicity of both types of proceedings as well as structural specifics in the respective areas of law that form the subject of the proceeding.

1. Asynchronicity

We believe that the different actors that may initiate the two types of proceedings as well as the time of their initiation directly influence the structure of the content issues. Recall that referrals are embedded in the regular court proceedings, whereas the constitutional complaint predominantly succeeds regular court proceedings. Local courts, state courts, and federal courts are all entitled to refer a question of the constitutionality of a statute to the FCC. Accordingly, in a three-instance court proceeding, a total of three courts have the opportunity to challenge the constitutionality of a law before a constitutional complaint can be filed by the individual citizen because—for the most part—constitutional complaints require the exhaustion of all legal remedies, including second and third instance appeals.

The referral may thus be considered a first turnoff to the FCC, which only the courts can take. Once this path has been chosen, the room for subsequent constitutional complaints by the involved private parties is substantially reduced. When substantiating their allegation of a fundamental rights violation, the complainant must engage with the standards previously developed by the FCC. Footnote 96 If the FCC, on the occasion of a referral for judicial review, found that a statutory provision is compatible with the Basic Law, a subsequent constitutional complaint must meet even higher standards and, therefore, is rather unlikely to be admissible.

Conversely, we expect constitutional complaints to mostly occur in view of topics that strike private individuals—and their respective lawyers—as constitutionally problematic but not the courts. As a result, issues will largely be left over for constitutional complaint proceedings in three constellations. First, the complainant believes that the regular courts’ specific application of statutory law is unconstitutional. Second, the complainant is convinced that the statutory law governing their case is unconstitutional, while the courts disagreed and, therefore, abstained from referring the question to the FCC. Third, by way of exception, a constitutional complaint can be filed without prior recourse to the regular courts, Rechtssatzverfassungsbeschwerde, allowing for constitutional complaints without even a theoretical possibility of a referral for judicial review.

Taking this asynchronicity of referrals for judicial review and constitutional complaints into account, we expect an uneven thematic distribution in both types of proceedings. We believe areas of law that are highly specific, rather unstable, and, therefore, not long-established under judicial law to be especially prone to referrals for judicial review because they are characterized by a large number of very particular statutory regulations and a high frequency of amendments to the law. This applies, for example, to social, tax, and civil service law. Footnote 97 As a result, qualitative scholarly law literature widely laments a “lack of consistent systematics” in these areas. Footnote 98 We believe that such an instability of the written law encourages regular court judges to doubt the constitutionality of the respective sectoral legislation. In contrast to this, we expect the topics of freedom of expression as well as matters of general criminal and private law to be overrepresented in constitutional complaints. Private and criminal law are characterized by a higher stability of the statutory law and its respective legal doctrines. Thus, we expect courts to be much less doubtful of the constitutionality of the underlying statutory law, which we believe to be predominantly perceived as well-tried and long-settled. If constitutional problems arise in these areas, we assume them to be framed as problems of an incorrect application of statutory law in the individual case. Footnote 99 Thus, in criminal law, for example, we would not expect many referrals for judicial review by the criminal courts concerning the constitutionality of the abstract penal provisions, but rather subsequent constitutional complaints of convicts regarding the application of the penal provisions in their individual cases.

Finally, particularly in certain areas of data protection law and constitutional law of the European Union, but also in criminal law, the direct path to a constitutional complaint is opened much sooner by way of the Rechtssatzverfassungsbeschwerde. In these cases, it is not necessary first to initiate a regular court and, consequently, there will be fewer situations in which a regular court might refer a question of constitutionality to the FCC. Therefore, we expect FCC decisions relating to these areas of law to originate in constitutional complaints rather than referrals for judicial review.

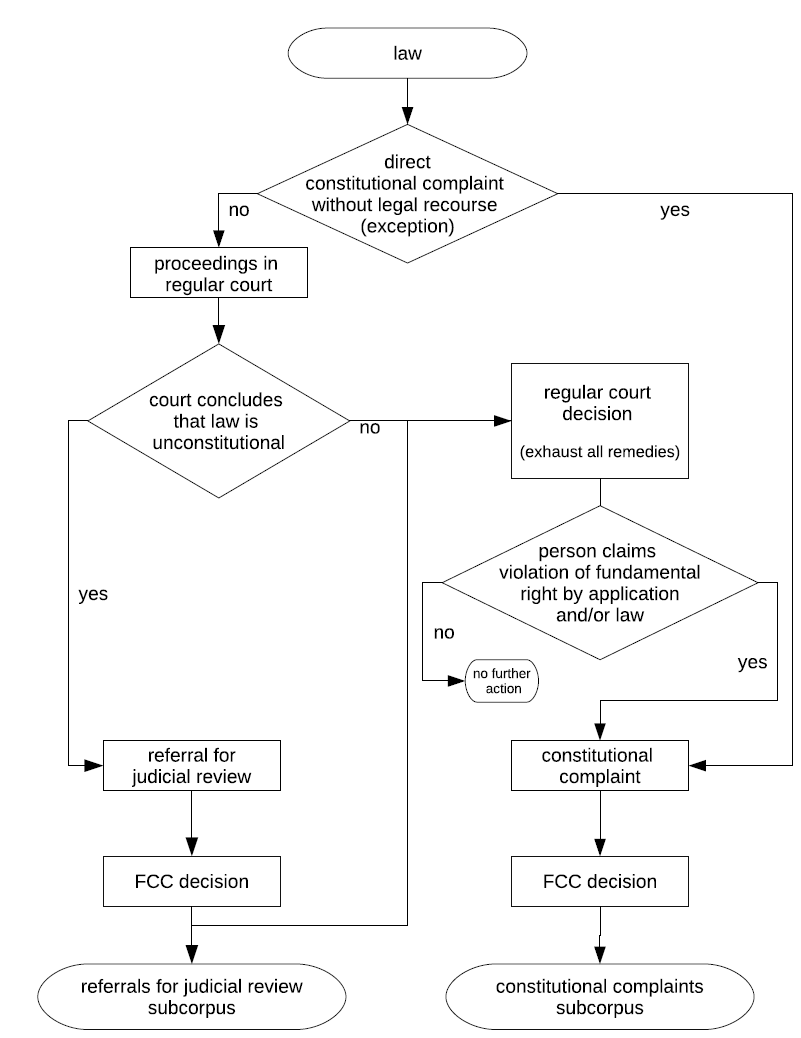

The flowchart in Figure 5 gives a simplified Footnote 100 overview of the different ways by which a statutory provision pertaining to a specific area of law may become the subject of a referral for judicial review or a constitutional complaint, thus contributing to one of the subcorpora.

Figure 5. Overview of possible paths by which a law—here, a statutory provision—may end up in one of the subcorpora (simplified, see fn. 100).

2. Structural Specifics

For areas of law that are increasingly open to interpretation, especially through general clauses, we expect a significantly greater presence in the subcorpus of constitutional complaints. We assume that topics related to private law will occur much less in referrals because the higher frequency of general clauses as well as the horizontal relationship between the private parties presumably yields a larger scope of interpretation than in other areas of law. This gives the judge more leeway for construing a statutory provision in accordance with the Constitution and, thus, prevents the judge from having to refer the case to the FCC. Again, the individual parties may not agree with such a harmonization of the statutory law with the Constitution by the regular court judges and file constitutional complaints. Consequently, while we expect much fewer referrals for judicial review in areas of law that are characterized by increased interpretive room, we do not believe this to confine constitutional complaints.

3. Areas of Law

In the present investigation, we use the term area of law and have chosen several particular areas for a closer examination. We are aware that they differ in size, that they may occupy different levels in a hierarchical order of areas of law, and that they may overlap.

It might appear desirable to develop a definition of the term area of law and a comprehensive taxonomy. However, within the scope of this study, this is neither feasible nor necessary. There have been several attempts to define the term area of law in the literature. Footnote 101 Yet, there are no universal, objective criteria for deciding whether a set of rules constitutes an area of law. Rather, these depend on historical, political, and other circumstances Footnote 102 and are the subject of a complex process of interaction between the legislator, legal scholars, and other members of the legal profession. Footnote 103 We, therefore, use the term somewhat casually in correspondence with our hypotheses, which does not call for a highly specific differentiation of potentially ambiguous cases.

Our choice of areas of law follows our hypotheses. It is by no means, however, incontestable. One may question, for example, whether an area of law such as freedom of expression is of the same status or significance as criminal law or social law, and how to deal with the intersections it inevitably forms with private, criminal, or other areas of law. Footnote 104 In its decision on the internal allocation of proceedings to reporting Justices, the First Senate of the FCC, chose to explicitly allocate proceedings concerning the “freedom of expression, information, broadcasting and the press” to a specific Justice, which indicates that constitutional court practice warrants a delimitation of this area of law. Footnote 105 In a similar vein, the Second Senate of the FCC allocated “proceedings from all areas of law” that predominantly concern the interpretation and application of Article 23 and, therefore, questions concerning the limits of European Integration to a specific reporting Justice. Footnote 106 The apparent expediency of aggregating these proceedings into a single department indicates that EU constitutional law can be considered an area of law for the purposes of this study.

With that being said, in the course of our examination, it became apparent that comparing a small area of law such as freedom of expression with a considerably broader, more comprehensive area such as private law might lead to results that are difficult to interpret. We, therefore, developed and tested more precise hypotheses relating to private law below in Section V.

III. Methods

We first compiled the subcorpora of constitutional complaints—marked by a file number containing the letters BvR—and referrals for judicial review—marked by BvL. Because our corpus includes decisions in cases where constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review have been joined according to § 66 BVerfGG, a third subcorpus containing only these decisions was created to avoid artifacts stemming from duplicate data and thus, lower-than-actual differentiation between proceedings. However, only sixty-six decisions in the corpus stem from joined BvR and BvL proceedings compared to 1935 decisions from BvR only proceedings and 817 decisions from BvL only proceedings. Footnote 107 We removed some court-specific words as well as some linguistic artifacts from preprocessing. Footnote 108

We then computed separate topic models for each of the subcorpora. The number of topics was chosen algorithmically through an optimization function provided by the spectral initialization in the algorithm by Arora, Ge, and Moitra—k = 0 flag in the stm package. Footnote 109 Thus, unlike in the previous analysis where the number of topics was set to twenty-five, in this analysis, the best initialization point for a partition into n topics was algorithmically determined and the statistically overall best partition was computed. This was done in the hope of extracting topic numbers that are better suited for the large size difference between the subcorpora. Despite the size difference of factor 2.3 between the two major subcorpora, the number of automatically extracted topics was nearly identical at ninety-two compared to ninety-five. Even in the small subcorpus containing only sixty-five joined case proceedings, the automatic extraction still yielded seventy-eight topics.

Due to some earlier technical issues, this initial exploration was performed under exclusion of thirteen relevant documents. We report the topic models generated for the incomplete subcorpora because these were the basis for the following word selection process. The final analysis in Section IV includes all 2,818 documents pertaining to the two types of proceedings.

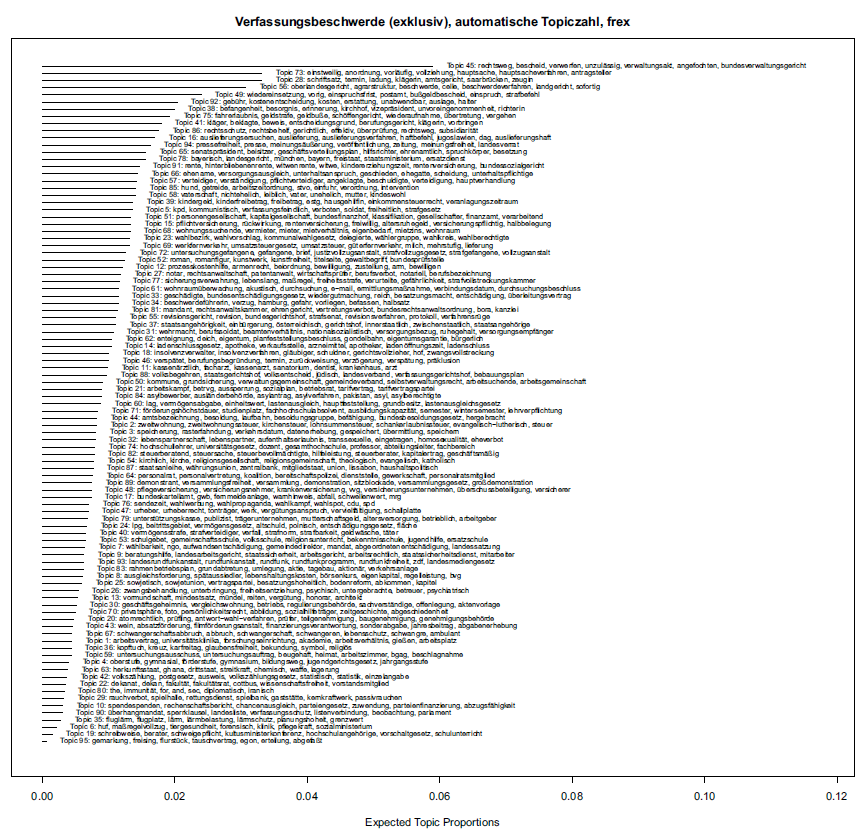

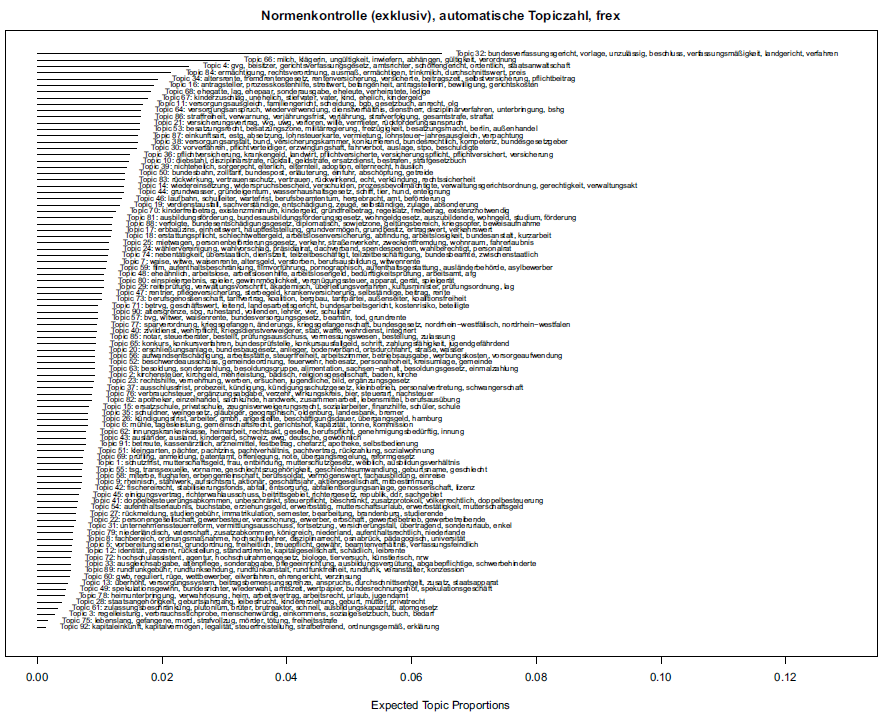

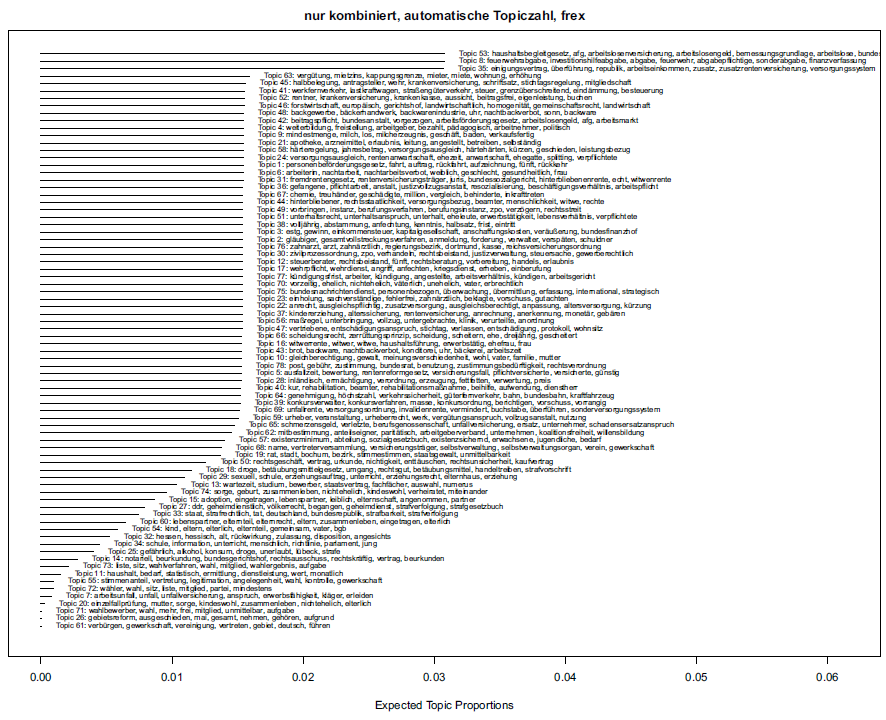

Figures 6, 7, and 8 show the expected topic proportions. Remarkably, the topics with the highest expected topic proportions both for the constitutional complaint subcorpus and the referral for judicial review subcorpus seem to concern questions of admissibility. Among the ten most frequent and exclusive words in the relevant topic for constitutional complaints, topic 45, are words such as rechtsweg, recourse to the courts, verwerfen, dismiss, and unzulässig, inadmissible. The respective topic for referrals for judicial review, topic 32, includes vorlage, referral, unzulässig, inadmissible, and verfassungsmäßigkeit, constitutionality. The subcorpus of joined proceedings contains no topic dealing with inadmissibility, which is not surprising given that proceedings may be joined only when they are admissible. Footnote 110 In order to circumvent some of the epistemological uncertainty discussed above, we then proceeded with a modified methodology compared to the previous analysis. Using topic modeling solely as a preprocessing tool to yield all relevant variants of the variables relevant to our hypothesis, for example, the words occurring under labels such as social law or EU constitutional law, we then performed an exact keyword search in the corpus. This process circumvents the insecurity from the lack of a topic definition, the lack of a functional interface between lexical co-occurrence and statistics—we define the topic through terms we consider relevant from an expert stance—and fuzzy topic boundaries—we perform an exact keyword search and no longer need to rely on topic prevalence estimations. The complexity as well as the argument is thus shifted back from the heuristic approach to the expert understanding of the subject, for example, the plausibility of the topics and their variables. At the same time, the topic model serves a genuine purpose in yielding the variants necessary for our search, and thus, providing a type of structured exploration or heuristic preprocessing. The latter is not dissimilar from a hermeneutic approach involving close reading, but is now applicable to much larger data thanks to the use of text mining techniques such as topic modeling. Footnote 111

Figure 6. A topic model of constitutional complaints in the official report series, frequent and exclusive words—frex, excluding decisions about joined constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review. The number of topics was calculated algorithmically.

Figure 7. A topic model of referrals for judicial review in the official report series, frequent and exclusive words—frex, excluding decisions about joined constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review. The number of topics was calculated algorithmically.

Figure 8. A topic model of joined constitutional complaints and referrals for judicial review in the official report series, frequent and exclusive words—frex. The number of topics was calculated algorithmically.

The necessity for methodological extension is further corroborated by the fact that the initial computation from 2,808 documents yields somewhat surprisingly divergent results compared to the model based on 2,818 documents. Footnote 112 While we are confident that central terms relevant to the areas of law chosen for our analysis were present in both, especially because the added documents make up less than 0.5 percent of the total corpus, the divergent numbers of topics—ninety-two compared to eighty-six for referrals and seventy-eight compared to eighty-six for the combined proceedings—as well as the differences in topic rank and word distributions per topic show the extreme sensitivity of statistical word-to-topic allocation. This lack of robustness of the method to derive conceptual topics from highly similar data underlines our point that topic modeling cannot be expected to produce reliable results that are valid for scholarly argumentation and should only be used as a tool for exploration and an aid in extracting candidates for further analysis.

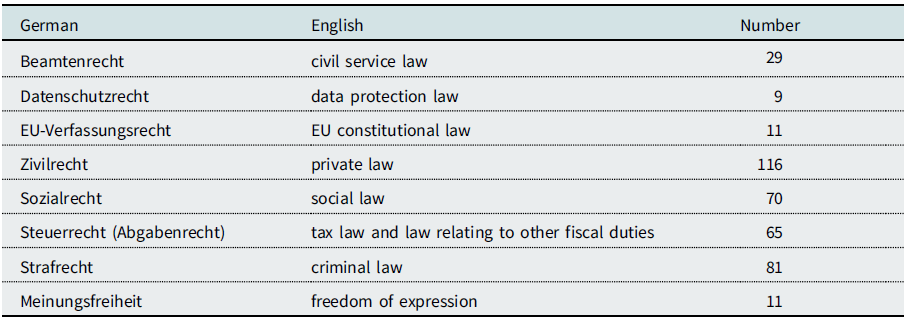

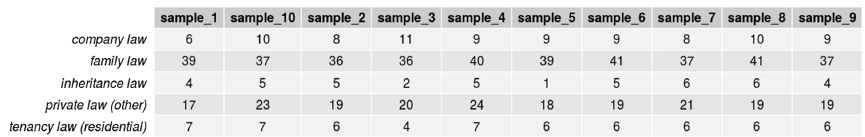

In a first step, three legal scholars independently identified the automatically generated topics related to the hypotheses and labeled them with higher-order labels such as private law or social law, as seen in Table 1. They also added a label, miscellaneous, for topics that were not clearly identifiable or not of interest for the present investigation. The labels were then discussed, and final labels were agreed upon. Finally, for each of the topics grouped under a label, we selected the words out of the ten most frequent and exclusive topic words that we considered relevant for the label, removed intruder words and added relevant words from the miscellaneous topic as necessary. Footnote 113 The chosen terms were then used as keywords for an exact search of the subcorpora.

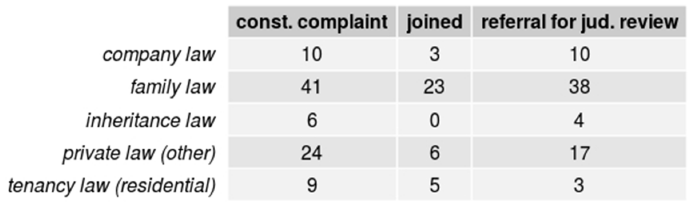

Table 1. Labels for manual annotation of topics and number of selected words

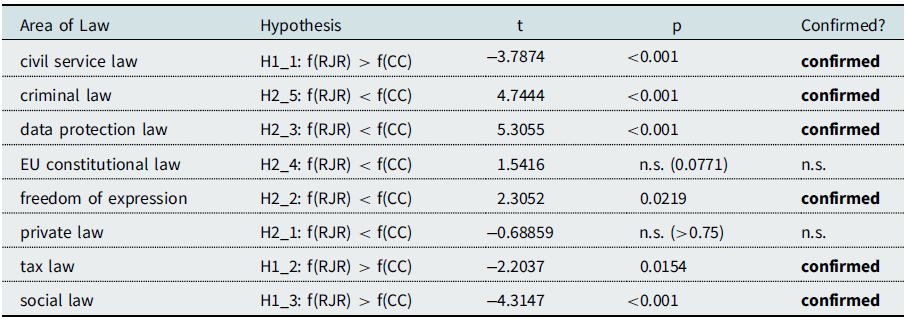

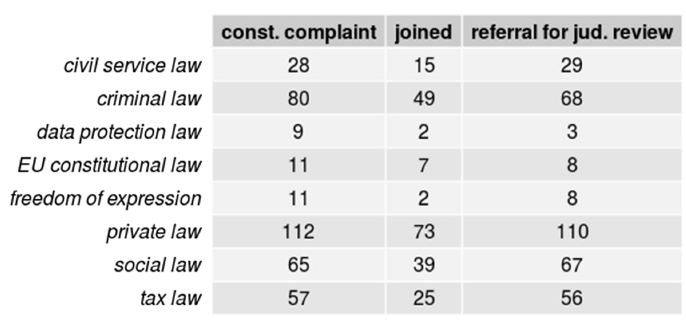

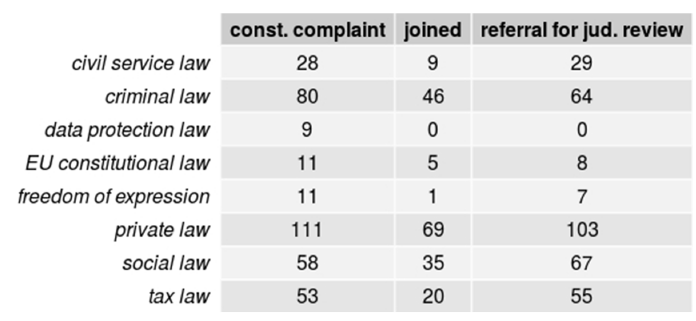

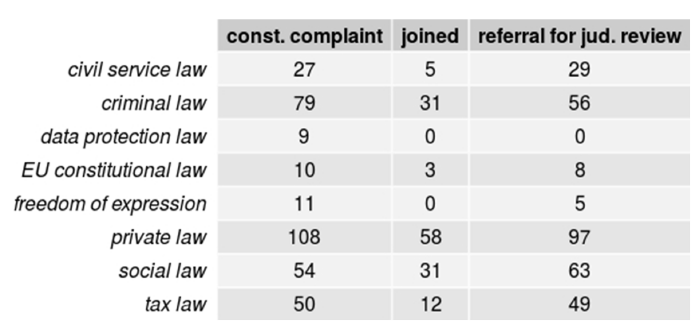

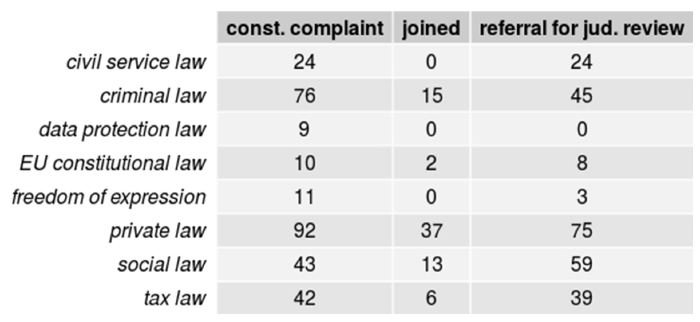

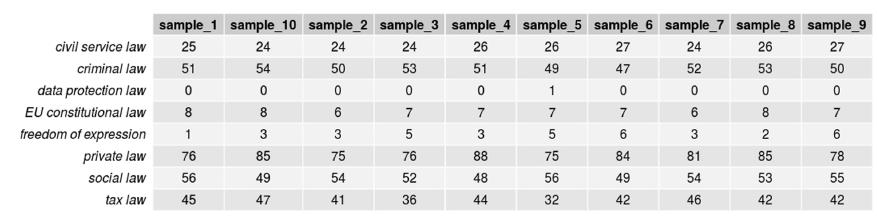

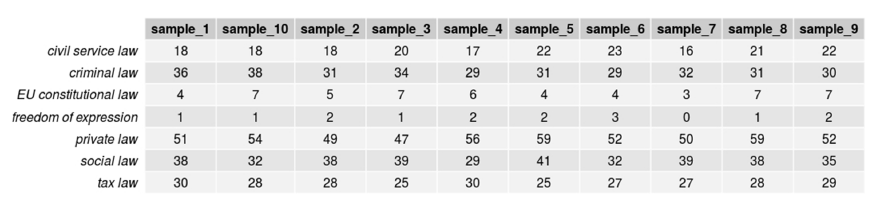

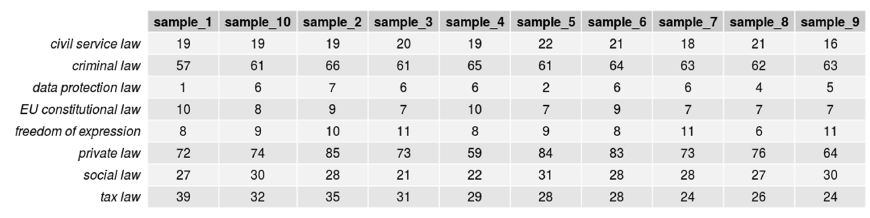

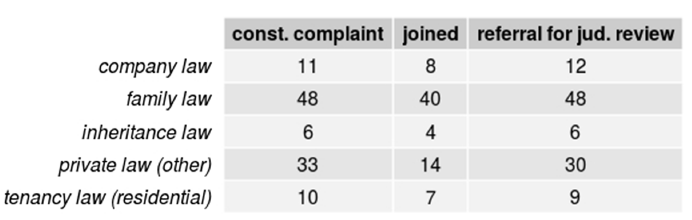

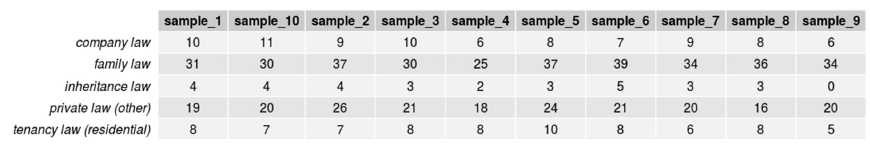

Table 2. One-sided paired t-test over mean frequencies of terms across ten 200-text samples. CC = Constitutional Complaint, RJR = Referral for judicial review

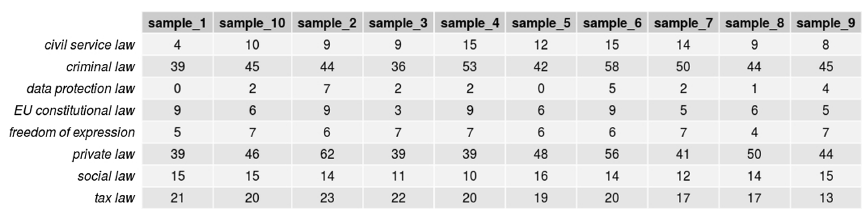

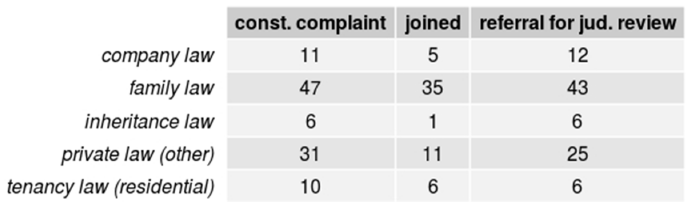

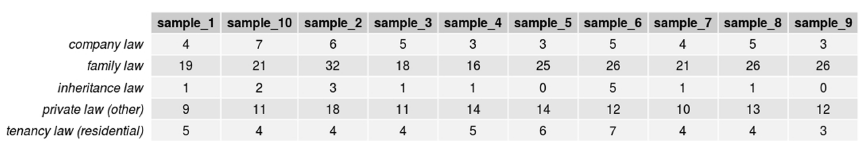

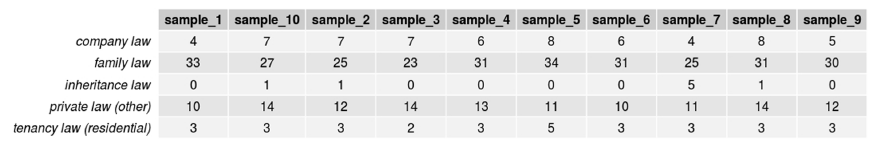

Table 3. Labels for manual annotation of sub-areas of private law and number of selected words

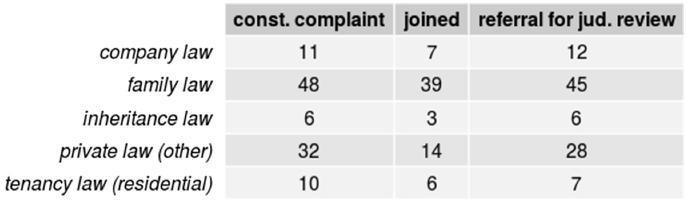

Table 4. One-sided paired t-test over mean frequencies of terms across ten 200-text samples. CC = Constitutional Complaint, RJR = Referral for judicial review

As can be seen from Table 1, labels subsume word sets of rather diverse sizes. This is in part due to differences in the granularity of the considered higher-order topics, such as private law compared to EU constitutional law, and partially an effect of the diversity and relevance of those topics in the context of the FCC. Where this interferes with direct comparability between categories, it will be discussed alongside the results.

IV. Results

1. Prevalence of Topic Terms

We begin by assessing the prevalence of topic terms for each subcorpus. If the listed terms are comprehensively relevant to the respective type of proceedings, the number of frequently appearing terms should be high. Considering the different sizes of the subcorpora and the power-law distribution of words, Footnote 114 it must be assumed that the number of frequent terms will be different for each subcorpus. Figures 9 through 12 show the number of terms per topic that occur ≥5, ≥10, ≥20 and ≥50 times in the respective subcorpus.

Figure 9. Number of terms per topic occurring 5 times or more per subcorpus.

From these results, it can be concluded that the selected terms are indeed relevant. Even in the subcorpus of joined proceedings, which contains only sixty-six documents, half of the selected terms, or more, for civil service law, EU constitutional law, criminal law, and private law appear at least five times. This may not seem like much, however, even in the largest corpora, more than half of all lemmata are hapax legomena—words that occur only once in the corpus. Footnote 115 While the topic modeling is based only on words that occur somewhat frequently, and rare words are explicitly filtered out, we later combined terms from different models that would not necessarily be expected to occur equally in all subcorpora. For the two larger subcorpora, there is little difference between the numbers for terms appearing at least five times and for terms appearing at least ten times, apart from data protection law vanishing from the results for the referrals subcorpus.

The numbers of topic terms that appear at least fifty times in the subcorpora for constitutional complaints, on the one hand, and referrals for judicial review, on the other hand, begin to diverge. Criminal law is represented by considerably fewer terms in the referral subcorpus than in the constitutional complaints subcorpus—forty-five compared to seventy-six— whereas social law is represented by remarkably more terms in the referral subcorpus—fifty-nine compared to forty-three—which is particularly notable considering that the constitutional complaints subcorpus contains more than twice as many documents as the referrals subcorpus. Overall, the analysis indicates that the selected terms are sufficiently frequent, procedure-specific, and relevant. It thus appears that topic models are useful as a fuzzy search tool for unknown variants because they do not yield too many false positives when combined with an expert screening.

Referrals for judicial review are the second most frequently initiated type of proceeding in the FCC, but they still amount to less than half as many documents compared to the subcorpus of constitutional complaints. The power-law distribution of words implies that the frequency of terms does not scale linearly. This means that a corpus that is 2.3 times the size of a smaller corpus will not contain 2.3 times the number of all terms of the smaller corpus. Instead, some words will be saturated both in the smaller and the larger corpus—hapaxes that remain hapaxes—, some frequent words will gain in absolute numbers, and many new hapaxes are expected to occur in the larger corpus. There exists no best practice on what to expect in terms of frequency distributions, because words are by definition an open class—new ones can be and are frequently created in a process termed productivity in linguistics—and the use of words is sensitive to factors such as language change, topic, register—situation or context, and the degree of formality. This makes it difficult to compare corpora of different sizes in terms of the lexical exemplars they contain. Footnote 116 To be sure that comparable numbers in the two corpora reflect actual differences rather than saturation effects, we compared ten samples of two hundred documents each from both subcorpora. Obviously, in the smaller subcorpus, the number of overlapping documents between samples is higher.

Figures 13 through 16 confirm that results are robust for equal-sized samples. Relevantly, they confirm our hypothesis that while all topics can and do appear in both types of proceedings, the internal distribution of topics is divergent. In referrals, for most samples, the ratio of frequent criminal law terms and frequent private law terms is between 1:2 and 3:5, and the ratio of frequent social law terms and frequent private law terms is about 2:3 to 1:1. In constitutional complaints, approximately the same number of criminal law terms and private law terms appear frequently in each sample, whereas noticeably fewer social law terms and civil service law terms appear compared to private law terms. It follows that, while there are not significantly fewer—probably even more—frequent private law terms in referrals for judicial review compared to constitutional complaints, the ratio within each subcorpus is in line with our hypotheses that tax law, social law, and civil service law terms are—relative to private law terms—more frequent in decisions on referrals for judicial review.

Figure 10. Number of terms per topic occurring 10 times or more per subcorpus.

Figure 11. Number of terms per topic occurring 20 times or more per subcorpus.

Figure 12. Number of terms per topic occurring 50 times or more per subcorpus.

Figure 13. Number of topic terms occurring 5 or more times in samples of 200 texts: Referrals for judicial review.

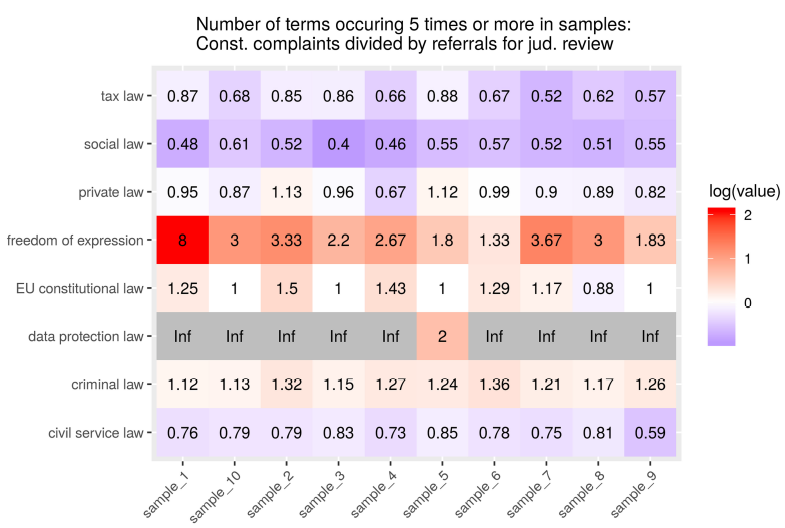

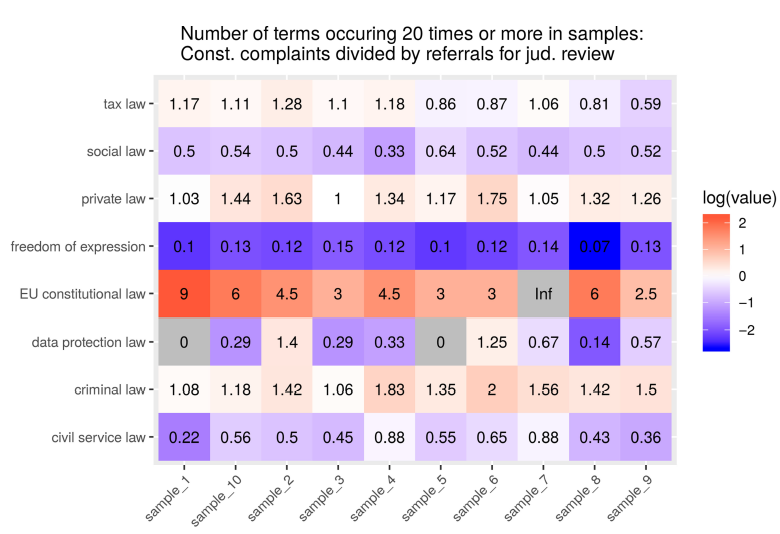

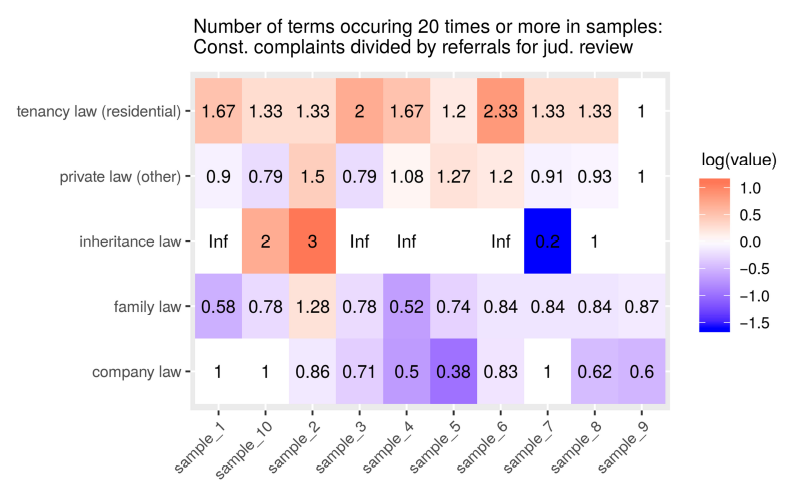

For a better comparison between samples, Figures 17 and 18 show heatmaps, where red tiles indicate a higher provenance of terms in constitutional complaints, while purple tiles indicate a higher provenance in referrals for judicial review. Again, the plots show clear tendencies for terms from data protection law and freedom of expression, and slightly less for criminal law, to be more prominent in the constitutional complaints subcorpus, and for social law, tax law, and civil service law to be more prominent in the referrals subcorpus. Footnote 117

Figure 14. Number of topic terms occurring 20 or more times in samples of 200 texts: Referrals for judicial review.

Figure 15. Number of topic terms occurring 5 or more times in samples of 200 texts: Constitutional complaints.

Figure 16. Number of topic terms occurring 20 or more times in samples of 200 texts: Constitutional complaints.

Figure 17. Ratio of the number of terms under the respective labels that occur five or more times in samples of two hundred documents, number of terms in constitutional complaint subcorpus samples divided by number of terms in the referral for judicial review subcorpus samples. ‘Inf’ indicates zero terms with a frequency of five or higher in the referrals.

Figure 18. Ratio of the number of terms under the respective labels that occur twenty or more times in samples of two hundred documents, number of terms in constitutional complaint subcorpus samples divided by number of terms in the referral for judicial review subcorpus samples. ‘Inf’ indicates zero terms with a frequency of twenty or higher in the referrals sample. Missing values indicate zero terms with a frequency of twenty or higher in either subcorpus.

To recapitulate the main hypotheses:

-

H 0: No difference in the frequency of occurrence of topic-relevant terms by subcorpus

-

H 11 – H 13: for civil service law, tax law, social law: frequency of occurrence in referrals for judicial review > constitutional complaints

-

H 21 – H 25: for private law, freedom of expression, data protection law, European constitutional law, criminal law: frequency of occurrence in referrals for judicial review < constitutional complaints

One-sided paired t-test statistics were computed on the mean frequency of each term across ten 200-text-samples. Relative frequencies from the whole corpus were not used due to the difference in size, 817 compared to 1,935 documents in the two subcorpora. Because word frequencies do not scale linearly, a simple division by number of documents would have skewed the results. The paired test was used because more frequent terms in general can also be expected to be more frequent in both subcorpora, effectively forming pairs. This yielded the following results:

While these results confirm our hypotheses in major aspects, they should be viewed with caution. Overall, there appears to be a tendency of topics to be more represented in referrals for judicial review compared to constitutional complaints. This effect may stem from the difference in corpus size— less noise or randomness—or it may be structural in the sense that it is possible that there are other systematically diverging topics filling parts of the distribution in constitutional complaints, but not referrals, and which are not yet considered in our hypotheses. To gain further insight, we performed an analysis over time.

2. Development Over Time

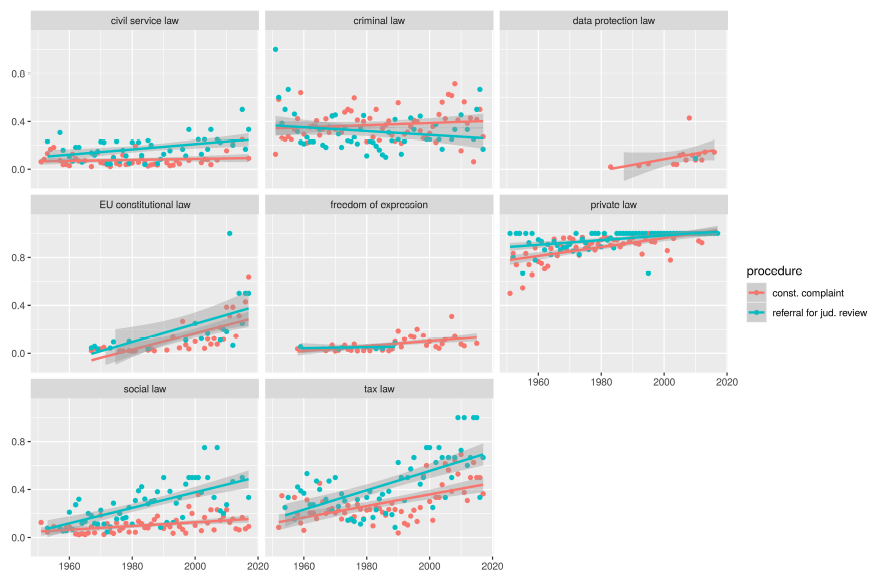

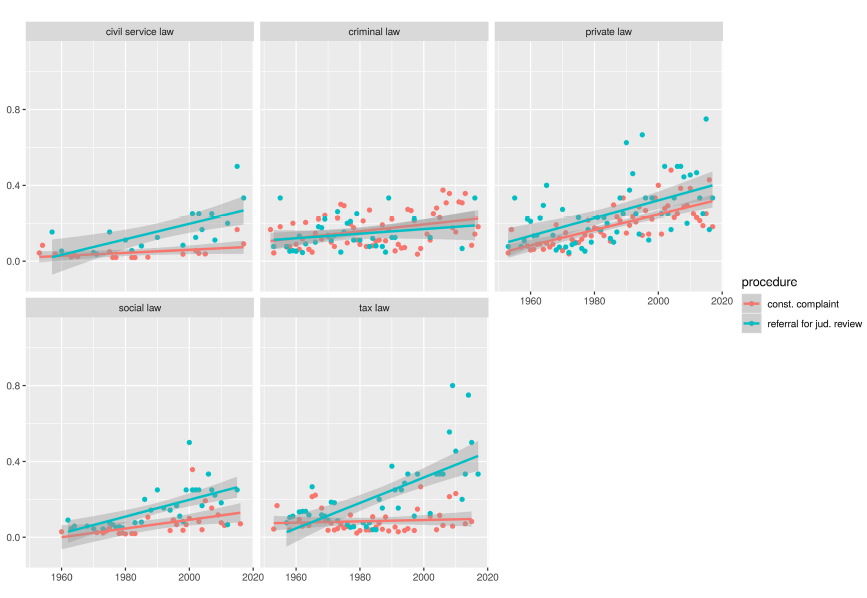

To see how the prevalence of a topic develops over time, it is necessary first to identify a topic. In classic topic modeling, the topic and its words are demarcated in a single process. However, because we refrained from working with those topics due to the epistemological concerns discussed earlier, we need a separate definition. Given that it is obviously unreasonable to expect all words pertaining to a label to occur in a single document, the question is what marks a useful boundary. As mentioned earlier, this is undefined in linguistics. There is no model of what might constitute a ‘topic’ of this kind and certainly no scalar quantitative model that would define the number of terms, their granularity, or their proportion. With words being an open class and ‘topic’ a concept with fuzzy boundaries and many possible levels of granularity, it is not to be expected that such a model can be easily developed from within linguistics either. It is possible that subject-internally, topic boundaries can be reasonably defined for various levels of granularity; however, best practices for this do not presently exist to our knowledge. Thus, we limit our definition to the approximation through two lower bounds: One of at least three topic-relevant terms in one document and one of at least ten topic-relevant terms. In Figures 19 and 20 we present the proportion of documents per type of proceedings containing at least three and at least ten terms from the respective labels.

Figure 19. Proportion of cases that contain at least three of the respective topic terms.

Figure 20. Proportion of cases that contain at least ten of the respective topic terms. Contains fewer panels because for the smaller areas of law there are no documents that include ten of their terms.

As we suggested earlier, the plots demonstrate that results from the previous section contradicting our hypotheses largely appear to be artifacts from corpus size or corpus distribution. In this analysis, however,

-

H 11 – H 13 for civil service law, tax law, social law: frequency of occurrence in referrals for judicial review > constitutional complaints are clearly confirmed, and increasingly so over time.

-

H 21 – H 25 for private law, freedom of expression, data protection law, European constitutional law, criminal law: frequency of occurrence in referrals for judicial review < constitutional complaints freedom of expression and data protection law are clearly more prevalent in constitutional complaints—confirmed. Criminal law is more variable, but it still shows a clear and increasing tendency to be more prevalent in constitutional complaints—partially confirmed. EU constitutional law is somewhat difficult to interpret because it appears to have made a shift since roughly the year 2000 and now is somewhat more prevalent in referrals for judicial review. This analysis would have required more fine-grained hypotheses over time. Private law seems to be an entirely different case. Data points converge to 0.9 over time, which indicates that in ninety percent of recent documents from both proceedings, at least three of the private law-labeled terms occur. This suggests that the list of labels contains terms that are not distinctive of private law. It also points towards a potential change in the language of the Court where some terms that were once more distinctive are now used more widely, particularly in constitutional complaints, as evidenced by the greater slope. This is further corroborated in Figure 20, where ten terms are still covered by ninety percent of some documents in the private law topic. It appears, however, that ten terms may be too limiting to see clear results. While not within the scope of this analysis, it would be interesting to see in future research how many and which terms are best suited to capture both conceptual and subject-specific topics and how this may differ between topics.

V. A More Detailed Analysis of Private Law

1. Hypotheses and Methods

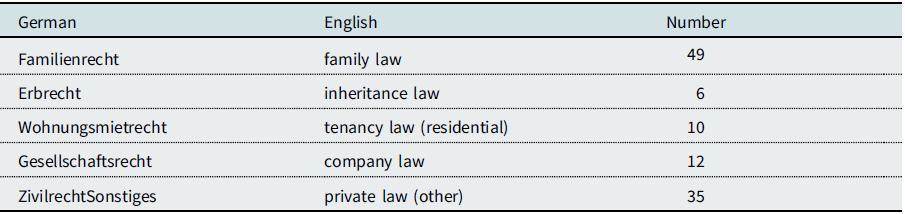

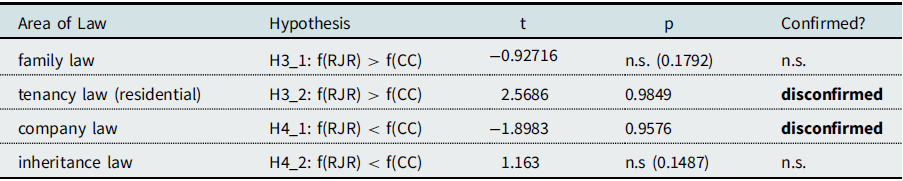

We have seen that the list of terms for private law may not be distinctive for this area of law and that ten terms are covered by ninety percent of some documents in the private law topic. Finding three or even ten out of 116 terms in a document is more probable than finding three, or ten, out of eleven or twenty-nine terms. It thus appears useful to divide private law terms into more fine-grained subtopics. According to the hypotheses we outlined above, we expect areas of law to be overrepresented among the referrals for judicial review if they are rather technical and characterized by frequent legislative changes. Areas of law that have changed less frequently and could develop a more settled jurisprudence as well as areas of law where statutes are characterized by a larger scope of interpretation are less likely to be referred to the FCC and will thus be more prominent in the subcorpus of constitutional complaints. The last-mentioned arguments might not be applicable to all of private law. Family law and tenancy law Footnote 118 come to mind as two sub-areas of private law in which the fundamental interests at stake may give rise to constitutional litigation and which have undergone substantial and recurring changes since the creation of the civil code, Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB), in the late nineteenth century. Footnote 119 In both areas of law, imbalances in negotiating power might lead to an increased relevance of compelling law that cannot be derogated from and which might make it necessary for the judge to refer the question of constitutionality to the FCC. This might be contrasted with cases concerning the law of—other—obligations where the aforementioned horizontal relationship is more tangible and where a judge might have more room for interpreting the law in accordance with the constitution. Furthermore, another aspect might influence the probability of a referral and that is the degree of Europeanization of the area of law. If an area of law is highly Europeanized, questions concerning the validity of a statute might be framed as a question of conformity with European Law and referred to the European Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling,Footnote 120 while constitutional complaints concerning the application of this law might still be admissible. While the full implications of European integration cannot be discussed in this chapter, we expect words concerning company law to appear more prominently in the subcorpus of constitutional complaints because this area of law is highly influenced by European law. Furthermore, we expect inheritance law, which has not been subject to many legislative changes, to be more prominent in the constitutional complaints subcorpus as well. We are left with a category of miscellaneous private law terms for which we cannot provide clear hypotheses Footnote 121 due to the diversity of the terms.

Again, three legal scholars independently labelled the former private law terms with these more specific labels and assigned the final categories in a discussion. We excluded four words which, after this second discussion, we considered to belong to social law or public law rather than private law.

2. Results

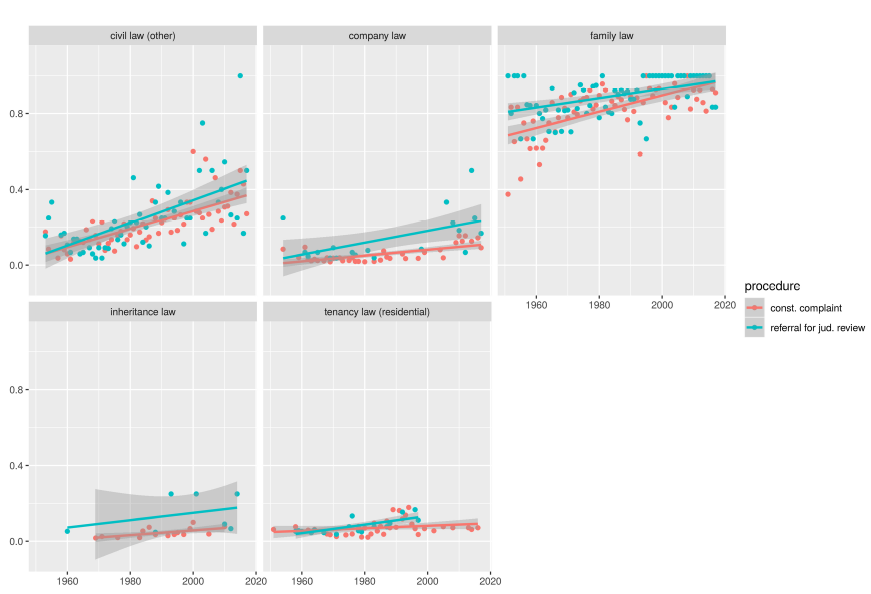

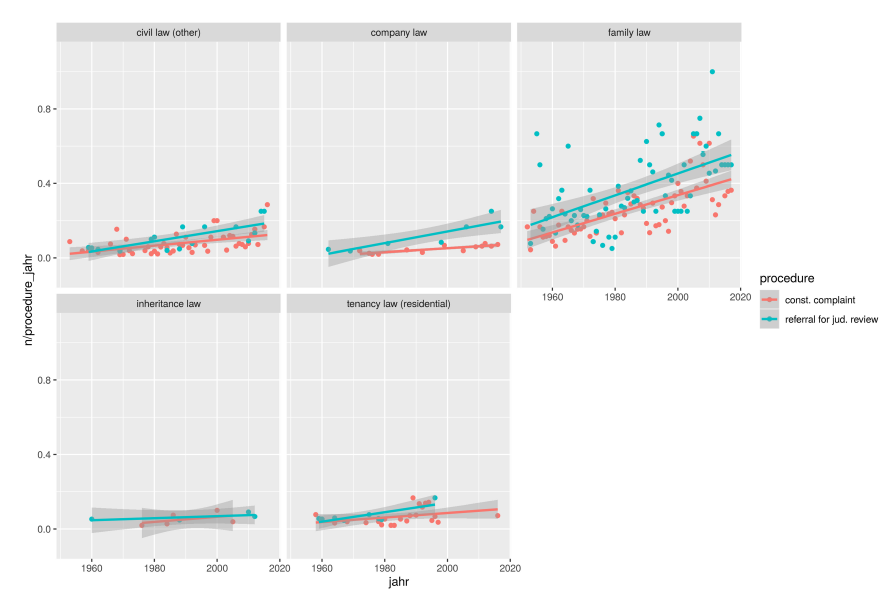

The number of topic terms occurring at least five or ten times per subcorpus is almost identical, as shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22. For topic terms occurring at least twenty or fifty times per subcorpus, Figures 22 and 23 show that family law, when compared to other private law, is slightly more prevalent in the referrals subcorpus. This is not the case for tenancy law. Company law also seems to appear more frequently in referrals for judicial review than in constitutional complaints. There is no clear distinction for inheritance law. The samples in Figures 25 through 28 provide a similar result.

Figure 21. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring five times or more in the respective subcorpus.

Figure 22. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring ten times or more in the respective subcorpus.

Figure 23. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring twenty times or more in the respective subcorpus.

Figure 24. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring fifty times or more in the respective subcorpus.

Figure 25. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring five or more times in samples of two hundred texts: Constitutional complaints.

The heatmaps in Figures 29 and 30 also indicate that tenancy law might indeed be more prevalent in the constitutional complaints subcorpus whereas company law, as well as family law, appears more frequently in referrals for judicial review.

Figure 26. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring twenty or more times in samples of two hundred texts: Constitutional complaints.

Figure 27. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring five or more times in samples of two hundred texts: Referrals for judicial review.

Figure 28. Number of civil law subtopic terms occurring twenty or more times in samples of two hundred texts: Referrals for judicial review.

Figure 29. Ratio of the number of terms under the respective labels that occur five or more times in samples of two hundred documents, number of terms in constitutional complaint subcorpus samples divided by number of terms in the referral for judicial review subcorpus samples.

Figure 30. Ratio of the number of terms under the respective labels that occur twenty or more times in samples of two hundred documents, number of terms in constitutional complaint subcorpus samples divided by number of terms in the referral for judicial review subcorpus samples. ‘Inf’ indicates zero terms with a frequency of twenty or higher in the referrals sample. Missing values indicate zero terms with a frequency of twenty or higher in either subcorpus.

Figures 31 and 32 show the proportion of cases that contain at least three and five words for the named areas of law. Footnote 122 We can see, as indicated above, that topics terms, in general, tend to be more represented in referrals for judicial review than in constitutional complaints. While tenancy law words were, at the beginning, represented in referrals and constitutional complaints almost equally, for the last twenty years they appear not to be represented in referrals with five or more terms anymore. Contrary to our hypotheses, we see that company law terms are increasingly represented in referrals.

Figure 31. Proportion of cases that contain at least three of the respective topic terms.

Figure 32. Proportion of cases that contain at least five of the respective topic terms.

As before, one-sided paired t-test statistics were computed on the mean frequency of each term across ten 200-text-samples. Civil law—other—was not tested because no clear hypotheses could be formed due to the high diversity of terms included.

Because our hypotheses have not been confirmed, we have to assume that our assumptions about which areas of law give more or less opportunities to initiate a referral are not correct for these areas of private law or that the topic terms chosen do not ideally represent the respective topics. As mentioned above, in particular concepts relating to family law, for example, marriage, spouse, unmarried, Footnote 123 and company law, for example, management, acquisition, conversion, may be relevant in other areas of law, such as tax law.

D. Conclusion and Future Research

The analysis performed in this study produced outcomes on a number of levels. Regarding the methodological contribution, we have shown a possible incorporation of topic modeling into the research process. Starting out with well-founded hypotheses, topic modeling was used to productively identify variants of predetermined variables—words pertaining to expert-defined topics. These were then validated by legal experts, thus avoiding the uncertainty of the heuristic procedure in the scholarly argumentation. The prevalence of the topics defined by this process was then examined. In a second iteration of the process, we refined our hypotheses to produce more detailed results. It was also shown that a small-scale comparison, for example, through the consideration over time or a sampling to equalize divergent corpus sizes, can help with the validation of unclear results.

The main result of interest to the constitutional lawyer and other observers of the FCC are the differences in topic prevalence in the two subcorpora. There is a tendency of referrals for judicial review to deal with social law, tax law, and civil service law while constitutional complaints are more likely to treat freedom of expression and data protection. This has been shown in the base topic model but becomes much more clearly pronounced in the topic-modeling-based exact search of topics as defined by experts, rather than statistically deduced. Results from this analysis confirm the initial hypotheses in most relevant aspects, which is most clearly pronounced in the distribution of topics on proceedings over time. Results suggest with great clarity that, despite the similar scope of protection of the two most relevant types of proceedings, there are quantitative differences in the content issues that reach the FCC via constitutional complaints compared to referrals for judicial review. While FCC statistics indicate that between 1991 and 2017 courts concerned with social law and tax law were responsible for sixteen percent and eleven percent, respectively, of all referrals for judicial review, only seven percent and three percent, respectively, of court decisions challenged were constitutional complaints. Whereas, for example, criminal law courts initiated fourteen percent of referrals and passed twenty six percent of the challenged decisions. Footnote 124 These statistics do not provide insights about smaller areas of law, such as civil service law.

While our hypotheses were formed based on the characteristics of the different proceeding types and areas of law, the method cannot conclusively provide a causal link between topic prevalence and those characteristics. Other contributing factors may lie in:

-

The regular courts’ “preferences” in referring questions of constitutionality.

-

– Drafting a referral for judicial review means additional work for the judge and the proceedings are stayed until the FCC has reached a decision, which can take years. The admissibility criteria are strict and there is a high risk that the FCC will consider the referral to be inadmissible. Consequently, judges will only refer a question of the validity of a statute to the FCC in exceptional cases.

-

– Some courts/jurisdictions may be less overloaded than others or may have more resources in terms of time or personnel. This might make referring a question to the FCC easier for some courts than for others.

-

– As far as civil service law is concerned, an additional motivation to refer questions of constitutionality might—in exceptional cases—result from the judge herself being affected by the law in question. Footnote 125

-

-

The FCCs “preferences” in admitting a constitutional complaint for decision according to § 93a BVerfGG and in deciding whether a decision, in either type of proceeding, should be taken by the senate or chamber.

-

Complainants’ differing perceptions of fundamental rights violations, as well as differing resources in terms of time and/or money.

The results for the different sub-areas of private law, however, do not confirm our hypotheses. This might be due to specific properties of those areas of private law or to mechanisms of private law litigation which have not been considered in our model. Furthermore, because our starting point was to dissect our previous topic of private law, the resulting sub-areas might not include an optimal choice of terms. It is also possible that some of the terms pertaining to our private law topic are not particularly salient or distinctive for specific areas of law. This is also suggested by the fact that, in the initial analysis, about ninety percent of all decisions contained words belonging to private law. More research is needed to resolve this.

Aside from these specific results, our study hints at several obstacles a legal researcher wishing to complement their research with quantitative methods might have to overcome. For example, experienced lawyers may write about areas of law with ease but in order to conduct quantitative research, a researcher must operationalize their research question and find countable proxies for this phenomenon of interest—in this study: keywords validated by constitutional law scholars. The same is, of course, true for other legal concepts that may become the focus of quantitative research. Moreover, we have shown a feasible process for developing testable hypotheses from legal knowledge and dogmatics.

Nevertheless, our choice of areas of law and their corresponding keywords is not perfect. Some aspects that remain for future research concern the scholarly modeling of the topics, that is, the ontology of the topics chosen. Because topics considered in the analysis are of very different granularity, some contain only nine terms, some over one hundred, it is justified to ask whether these ‘topics’ are of the same ontological status. This is not simply a pragmatic question but one that concerns the implicit or explicit theoretical model involved. Some topics of equal size, relevance, or similar jurisprudential categorization may be indeed reflected in very different numbers of terms. It is, however, also possible that the categories are not ideally chosen in this regard.