Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a lifelong relapsing–remitting condition, characterized by troublesome symptoms including fatigue, pain, and bowel urgency. These symptoms can persist even in clinical remission and have a debilitating impact on social, work-related and intimate domains of life. Symptom self-management can be challenging for some patients, who could potentially benefit from an online self-management tool.

Aims

We aimed to understand patients’ symptom self-management strategies and preferred design for a future online symptom self-management intervention.

Methods

Using exploratory qualitative methods, we conducted focus group and individual interviews with 40 people with IBD recruited from UK clinics and from community-dwelling members of the Crohn’s and Colitis UK charity; data were collected using a digital audio recorder, and transcribed and anonymized by a third party (professional) transcriber. We used framework analysis for focus group data and thematic analysis for interview data.

Results

The data provided three core themes: ways of coping; intervention functionality; and intervention content. Participants attempt to manage all three symptoms simultaneously, recognizing the combined influence of factors such as food, drink, stress, and exercise on all symptoms. They wanted an accessible online intervention functioning across several platforms, with symptom and medication management, and activity-tracking features.

Conclusions

Patients reported numerous ways of self-managing symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency/incontinence related to IBD and expressed their needs for content, design, and functionality of the proposed intervention. Based on this and existing intervention development literature, the IBD-BOOST online self-management intervention has now been developed and is undergoing testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term for a group of chronic idiopathic disorders characterized by a dysregulated immune response to host intestinal microflora, which causes inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [1]. The commonest forms of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) which can affect the GI tract anywhere between mouth and anus, ulcerative colitis (UC) which affects only the colon, and IBD unclassified (IBD-U), a definition used when a case cannot readily be classified as either CD or UC [2]. Inflammatory bowel disease is a chronic health condition with a prevalence rate of 827 per 100,000 in Europe, and 668 per 100,000 in North America [3]. It has an often-unpredictable relapsing–remitting disease pattern which causes bouts of gut inflammation with symptoms including diarrhea, pain and rectal bleeding/bloody stools, weight loss, and fatigue.

Medical management to control inflammation dominates IBD care. However, patients report continuing IBD-related fatigue (41%), abdominal pain (62%), and difficulty with urgency and incontinence (up to 75%) even in remission [4,5,6]. The patient’s illness experience, and consequently their quality of life can be severely impacted by these symptoms, affecting the ability to work and socialize [6, 7]. Patients’ experiences of these symptoms are not the priority in medical consultations, where the focus is on symptom assessment using disease activity indexes and objective scores of inflammatory markers, such as fecal calprotectin, and patients may feel their concerns are not addressed [8, 9]. Consultations with IBD Clinical Nurse Specialists (IBD-CNSs) often do give patients more time to talk about their illness experiences and the impact of symptoms, but there is limited research on self-management interventions to improve these symptoms for IBD-CNSs to draw on when advising patients.

Self-management has been defined as “the individual’s ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition” [10]. Self-management is a core feature for any patient with a chronic illness [11,12,13]. It puts the patient in charge and in control of the condition they live with, acknowledging their expertise in their disease. Additionally, healthcare services globally are over-stretched, or difficult to access due to cost or availability. Self-management options independent of healthcare services, which do not also over-burden the individual, are needed to promote patient independence in illness management, and reduce the burden on healthcare services.

The IBD-BOOST program [14] (led by the senior author) builds on over a decade of the teams’ research into these three symptoms and aims to address patients’ concerns by developing an online self-management intervention for fatigue, pain, and urgency/incontinence, with substantial patient input at every stage to ensure that what is developed is grounded in and meets the needs of patients living with IBD. We therefore aimed to collect data on the current self-management strategies that individuals with IBD use to cope with the symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency, and their preferred components for the design and delivery of an online self-management intervention. The research questions were: (a) How do individuals with IBD currently manage symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency and what have they found helpful/unhelpful? and (b) What opinions do individuals with IBD have about the format and content for an online self-management intervention?

Methods

Study Design

Exploratory qualitative research [15] was used to address the research questions. This methodology is informed by the post-positivist paradigm which argues for an ontological (what it means to “be”—for example, human, chronically ill) perspective and therefore a subjective exploration of topics; it is recommended when there is a dearth of evidence and/or for first investigation of a novel topic [16]. It encourages a flexible approach—for example, additional questioning when an unexpected topic of interest emerges during an interview—and uses standard qualitative methods (focus groups, interviews, textual analysis techniques), often without a specific underpinning philosophical framework such as is found, for example, in phenomenology. It is widely employed to gain insight into patients’ illness experiences.

Recruitment and Sampling

Using purposive sampling with maximum variation to attract patients from diverse ethnic groups, genders, ages, and IBD sub-types, we recruited from clinics in three hospitals across northern and southern England and online from members of the UK national Crohn’s and Colitis charity. Inclusion criteria were: endoscopically confirmed diagnosis of IBD (self-reported by respondents), at least 18 years old, current or past experience of one or more of the symptoms of fatigue, pain and/or urgency/incontinence related to IBD, ability to give informed consent, understanding and speaking the English language as there was no scope for translation.

Data Collection

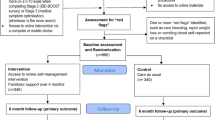

Data were collected by using two methods: (a) secondary analysis of data collected via focus groups, convened originally for a related study that explored the daily experiences and impact of this triad of symptoms (17) (Fig. 1). Focus groups are beneficial for identifying topics of relevance but do not always give rich data, since the group format can prevent detailed exploration. We therefore also conducted: (b) individual telephone or face-to-face interviews with new participants, to explore further the issues identified during the secondary analysis of focus group data—how people self-manage their IBD symptoms and what they want from an intervention.

Data capture and relationship with the previous work; white boxes denote the previous related study [23] and gray boxes denote the current study

We used the same topic guide (Table 1) for focus groups and interviews, which was developed in partnership with the IBD-BOOST Patient and Public Involvement panel and informed by our previous research [4, 9, 17], and our knowledge of self-management programs and online intervention development related to IBD and other chronic conditions [13, 18,19,20]. Individual interviews offer the opportunity for disclosure from people who may feel less comfortable in a group setting, or are unable to physically attend a group meeting, thereby enabling them to participate. Interviews were digitally recorded, and transcribed and anonymized professionally.

Data Analysis

Focus Group Data

Focus group data were analyzed using a framework approach. Framework analysis is appropriate when there are a priori issues to address (in this case, the three specific symptoms, ways of managing these, and preferences for intervention content, design, and functionality) [21]. It includes five core stages: familiarization; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; and mapping and interpretation [21, 22]. The robust analysis process, overseen by LD, has been reported previously in full [23] and was replicated here.

Interview Data

Interview data were analyzed thematically [24, 25] by SF, KS, and JB; they completed initial analysis by reviewing and coding transcripts independently, before meeting to organize codes into preliminary themes. These were then reviewed and refined iteratively by experienced qualitative researchers CN and LD, to generate the final themes and sub-themes. Standard features within Microsoft® word-processing software (tables, comments, highlighting) were employed, rather than specialist qualitative analysis software. The findings presented below are based on the combined data from the secondary framework analysis of the focus groups data, and the thematic analysis of the individual interview data.

Trustworthiness was assured through diligent rigorous processes (independent, then shared analysis over several rounds, revisiting transcripts for clarification of meaning, group discussion, and contribution by individuals with IBD to the analysis process). Credibility and dependability are demonstrated by the relationship between the research question, the themes arising from the analyses, and the verbatim extracts which verify those themes [26, 27].

Results

Forty individuals with IBD participated, via either one of five focus groups (N = 4, 7, 6, 6 and 3) originally convened for a previous related study [23] or an individual interview (N = 14; telephone, N = 3; face to face, N = 11); 22 participants were female; ages ranged from 23 to 60 years; diagnosis: CD (n = 21; UC (n = 17); IBD-U (n = 2); all had experience of the symptoms of interest (Table 2) and for many, these symptoms were quite, or very troublesome. Three main themes, each with sub-themes (Fig. 2) reflecting effective self-management strategies and need for intervention and support, were identified in the data from both the focus groups and interviews:

-

1.

Ways of coping: practical strategies; managing stress and emotions; breaking down isolation and gaining support

-

2.

Intervention functionality: platforms, accessibility, and usability

-

3.

Intervention content: symptom and diet trackers; practical and emotional self-management information, advice, and techniques; access to professional support.

Each theme is described with relevant quotes from a variety of participants (focus groups FG; interviews INT) with anonymous identification numbers for male (MP) and female (FP) participants, for example: [FG1:MP3] or [INT4:FP].

Theme 1: Ways of Coping

Participants reported several strategies for managing their symptoms more effectively, including practical techniques for dealing with fatigue, pain, and urgency, methods for coping with stress and emotions, and preventing themselves from becoming isolated by seeking and securing support.

Practical Strategies

Symptoms do not occur in isolation but are inherently inter-related in a complex interdependent manner. Participants therefore rarely just manage fatigue or pain, or urgency, but recognize that addressing perhaps the current most pressing symptom, will also have beneficial effects on other symptoms:

Symptoms have got better, as a result, I think, of a combination of the lifestyle change and diet change and the regular use of my medication [INT8:FP]

Diet and hydration were prominently identified. Detailed attention to diet proved beneficial but also highly individual:

I just try and eat as much fruit and veg as I can, cook from scratch, and avoid any processed food [INT6:MP]

While some could not, for example, eat spiced foods, yoghurt, dairy, or any form of carbohydrate, others could without negative consequence. Working out what are “safe” and “dangerous” foods (in terms of aggravating symptoms of IBD) was a highly personal but necessary endeavor:

I’ve noticed things such as certain greens, certain vegetables, very fried or greasy foods will definitely make me worse … the next day, I’ll have a lot of problems [FG1:MP1]

Attending to diet and hydration needs was a routine rather than rescue activity; taking one’s “eye off the ball” could result in worsening symptoms:

I’ve still got to be conscious about keeping hydrated even when I’m not having a flare because the knock-on effects is if I’m not hydrated, the fatigue will kick in [INT10:MP]

Participants reported the coping strategy of carrying equipment to enable them to “clean-up” in the event of urgency/incontinence:

I always travel with spare pants, towels, sanitary towels, wipes … I have a little pouch that I carry around with me [INT3:FP]

Although useful, this strategy deals with the consequence (incontinence) of the symptom (urgency) rather than resolving it. For some, this is the best they can achieve while for others, it is a “security blanket”—having the equipment they need with them reduces anxiety and likely reduces urgency. Others also reported taking positive steps to mitigate risks:

If I’m going to eat out somewhere and I’m nowhere near a toilet or I don’t know where there is going to be a toilet, I’ll take two [anti-motility drugs]. I even have some in my wallet. I’ve got some now. [FG4:MP2]

Although it could prove difficult for some as physical activity could exacerbate urgency, exercise was considered beneficial, especially in coping with fatigue:

People say, ‘Why don’t you give [the exercise] up, you’d be less tired if you gave it up’ … and I know that that is not true, because I found that exercise is the one thing that makes me seem kind of OK [FG3: FP3]

Others agreed, explaining that exercise resulted in increased, rather than depleted, energy levels:

If I go out for a short jog or a long run and do some exercise, generally I find that gives me more (energy). I feel more alert, I feel like I’ve got more energy in the tank after a few hours than I would (have) if I was just in bed or sat at home [INT6:MP]

For others, there was a beneficial link between activity and emotional well-being that came from managing symptoms with exercise:

Exercise is as much of a mental release and relief as it is a physical one. It’s probably one time when I’m playing sport or doing exercise I’m not thinking about my Crohn’s, I’m just really concentrating on what I’m doing, focus on that, enjoy that [FG3:MP2]

Naturally, sleep was reported as important for coping with fatigue, but a crucial element was also “permitting” oneself to sleep and rest as needed:

I try to get the right amount of sleep and if I feel like I’m just too exhausted to do anything, then I just try and rest [INT8:FP]

Managing fatigue also involved taking regular breaks during the day, striking a balance to avoid becoming completely exhausted:

It’s a balance between doing as much of what you want to do but knowing your limits and giving yourself a break when you need to [INT4:FP]

and achieving that balance through “pacing oneself” to prevent excessive fatigue:

I try not to get to that point where I tip, which is why I pace life a bit more than I used to. So I’m quite conscious of being on top of fatigue [FG3:MP1]

Typically, participants experienced their worst pain during a flare, alongside other deteriorating symptoms, but many had a persistent low level of pain or discomfort, and used various techniques for managing this:

I always found that the pain was more of an issue when I wasn’t doing anything, so being active and keeping on with things I didn’t notice it so much and it’s when you stop that it’s there [FG4: FP2]

Other methods included slow-release morphine patches to give better pain control, holding external heat sources such as a heat pad or hot water bottle against their abdomen, or resting. Broadly, participants tried to avoid taking regular analgesics including prescribed medications, due to concerns about addiction and side effects.

Managing Stress and Emotions

Many participants acknowledged the impact of stress on their symptoms and reported numerous self-care strategies, including changing their employment type and/or working pattern:

I quit my job basically because I was working in marketing, it was very high pressure, lots of deadlines and basically because I was stressed at work it was really making my symptoms bad [FG1:FP2]

Others had found that psychological and talking therapies gave them a sense of emotional control:

I’ve also been doing some talking therapy stuff – it feels like you’re taking action and bringing at least an element of control to the situation [INT2:MP]

Mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and Pilates exercises were reported as beneficial:

I haven’t had a flare up since I’ve introduced a bit of mindfulness [INT6:MP]

Mindfulness was explained as:

… coming back to the moment—not being so caught up in thoughts and in my head where I spiral off into “what if? what if?”—lots of negative thoughts. It’s bringing it back to breathing and that for me helps to manage anxiety and not get so stressed about things [FG1:FP2].

Coping well with symptoms was usually a combination of factors:

It’s a psychological thing; if I just feel good about everything, in combination with the medication and the diet, I tend to have zero problems [INT8:FP]

Participants also talked about learning to see the patterns between behaviors and symptoms, to then understand and change behaviors accordingly:

It’s generally just about trying things, see what happens … then when I’m feeling better, I try something again one time, a small quantity [of food] next to a toilet and see what happens. And if it still is a no-go, then I’m right where I need to be [FG3:FP3]

While keeping track could be managed informally, as above, several participants advocated keeping diaries to create a reliable aide memoire in the midst of their otherwise busy lives:

I monitor it when I’m well so that I can see when the symptoms start to deteriorate so that I can catch things early or before because if you are busy it might be a few weeks before you realise actually things are a bit worse [FG1:MP1]

Breaking Down Isolation: Gaining Support

Participants described the importance of avoiding social isolation, even if this meant changing their social networks:

It is different in terms of socialising now, but it’s fine. I’ve found a place whereby I’ve got friends who do understand, so that’s good [FG1:FP1]

Gaining support usually necessitated being open about one’s situation:

I’ve found it best to be perfectly honest with people; it’s easier for me to just tell everybody, and people accept that I won’t eat everything that’s on the plate, and they don’t get upset anymore that I’m leaving half of it [INT3:FP]

Participants also described positive relationships with clinicians which add to their own sense of emotional control, and “ownership” of their disease:

[My doctor] said, ‘This is what I’m looking at … what do you want to do?’ … and that’s what I need so I can say to her ‘Okay, well these are the options, what do you think if we do this?’ and she says, ‘Yes, I agree with you.’ And we discuss it. She doesn’t tell me what I should be doing or feeling. This makes an enormous difference’ [INT9:FP]

Others were able to benefit from understanding employers:

What I’ve found really helpful is actually working from home… my work luckily brought in flexible working and home working and my boss was quite supportive with me working from home when I needed to. So, the days where I was going to the toilet 14 times a day, the bathroom was two steps away from where I was sat [FG4:FP3]

For some, these benefits came from telling employers about their IBD:

I’ve got good employers—I start at 12 and I finish at 6 pm which means no mornings. I don’t have to be worried about early mornings [increased bowel activity] and even if I go in late then they understand, because I’ve told everybody what I’ve got [FG1:FP1]

Support could also come from online groups and forums; participants appreciated that these chat rooms gave them access to others “going through the same thing” which reassured them that they were not alone:

The Crohn’s forum on Facebook (is) quite good. There are tens of thousands of members … and you can put a question up and get an answer almost straight away. I think that’s quite helpful just because you know people are going through what you are going through [INT10:MP]

Theme 2: Intervention Functionality

Participants were clear about how they wanted the proposed online intervention to work.

Platforms and Accessibility

Participants wanted the intervention available across several platforms:

Just easily accessible: HTML, internet, apps [FG3:MP4].

There was particular enthusiasm for an app:

because it categorises activity and shows you trends and relationships which you might begin to know in the back of your head, but here it is in black and white [FG3:MP1].

Online provision was seen as a welcome opportunity:

I think it’s good [to be online] because it’s something that not everyone is comfortable talking about in person [FG4:FP3]

Usability

Participants wanted the online intervention “to be easy”:

… if it’s something clunky then you’re just never going to use it – it has to be user-friendly [FG3: FP1]

They also wanted something they could dip in and out of, as needed:

I like the idea of modules you can work through [FG6: FP1],

Participants proposed that modules could provide content relevant to the individual’s needs that could be easily and quickly accessed:

You could start out with a prescribed [online] course, and then when they want to come back to it they can go to specific points [FG3: FP3].

This participant explained that this approach would prevent people who had already visited the site several times from having to “trudge through” the entire content to get to where they needed to be.

Theme 3: Intervention Content

Participants appreciated that an online self-management intervention could not contain every available piece of information about IBD which might benefit patients but stressed the importance of including symptom and diet trackers, information, advice, and techniques, and enabling access to professional support. These, as well as signposting to other sources of help, were perceived as central to successful symptom self-management.

Symptom and Diet Trackers

Because IBD is unpredictable, participants wanted to be able to monitor their symptoms efficiently to detect patterns, and spot early signs of deterioration:

My symptoms seem to get worse very gradually, and I seem to adapt to each little increment and before I know it I’m up here [indicates height], but I should have gone to the doctor there [indicates depth]. So [a tracker] could show that actually you’re on a trajectory here, you’re steadily getting worse and you haven’t noticed [FG3:MP5]

Others suggested that such a system might also forewarn them, on the basis of previously collected data:

what you need is something that interprets that data in some way dependent on your symptoms … something like that would be really useful. It would start saying, “last time you did this, that happened” kind of thing. [FG3:MP1]

Participants had already confirmed that diet—what to eat and what to avoid—is a very individual aspect of symptom management in IBD. However, they felt that tracking the relationship between diet and symptoms would be helpful:

To be able to track foods … so what I’m eating and then looking back and seeing how has my diet changed in the last couple of weeks [and] is that why I’m maybe not feeling as good as I was a few weeks ago? [FG1: FP3]

For some, this would take the focus off bowel activity, which is often used by healthcare teams as a marker of efficiency of medications, and perhaps acknowledge other quality of life aspects of IBD:

It would be good to have [a] food [tracker] as opposed to how many times [I’ve been to the toilet] because they’re always asking me that, every time you go to the [clinic] they say, how many times do you go a day?. [FG6:FP4]

Tracking is, of course, only as good as the data that is entered, and participants felt an online tracker would be easier to manage than paper:

It’s good to track because I tried writing it, but it is a big faff writing it down … you forget to write it down. You might at the end of the day be like ‘oh … I’ll just type it in rather than get my book out and write it all out. [FG6: FP3 & FP1].

The “evidence” that symptom trackers could provide was considered potentially useful during clinical consultations:

You can show your consultant [how you’ve been] over the last three months. There’s something visual that you don’t have to explain too much, because you’re in a bit of a brain fog and you can’t really remember, but something like a graph … tracking multiple [or] individual symptoms [FG3:FP2]

Practical and Emotional Self-Management Information, Advice, and Techniques

Participants suggested that an online self-management intervention should include information aimed specifically at those only recently diagnosed:

If people know when they are first diagnosed that it can take quite a long time to work out for yourself, it could take months. It took me a year to work out that chocolate was one of the things that was triggering me. There will be ups and downs before you work out, “OK, that’s a good thing, that’s a bad thing.” [FG3:MP5]

They felt that knowing, to some extent, what to expect, would make the adjustment to living well with IBD somewhat easier:

If someone had said at the start that there is no specific timeline, and you will start to get the hang of things, and then things will feel like they’re changing, but you’ll get the hang of things again [FG3:FP3].

Participants suggested a wide range of information which could be useful in helping patients self-manage their symptoms, including advice about diet. Rather than expecting clear instructions on what to eat or avoid, participants wanted advice which would enable them to decide what worked for themselves:

Just advice on diet would be helpful … rather than “don’t have any carbohydrates, don’t have any dairy, only have these [foods]” … that just confuses you and you end up getting weird diets … so you feel you are making an informed decision [FG6:FP3]

It was also recommended that information on dealing with stress, and improving mental health and well-being, was made available. Participants felt that access to resources such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, and counseling would be helpful:

I think [counselling] would be something that would be really, really beneficial, especially for people that were newly diagnosed because before you know it, you’re in this mental cycle where you’re beating yourself up for things that are beyond your control and it completely knocks your self-confidence … if people were equipped psychologically with the tools to think of the different ways to do things, maybe that would have a better impact on their physical health [FG3:FP3]

Participants had themselves found that techniques learned through CBT and from specialist psychologists were helpful in changing their ways of thinking about their disease and symptoms, giving them positive strategies for effective self-management and boosting their mental well-being, and they wanted these resources to be available to others:

If you get referred to pain management, they have specialist psychologists that help you. Their aim is to not give you more drugs because they know drugs don’t work … they’re going to help you deal with the fact that you are in pain [FG3:FP3]

The key benefit, they explained, was that these approaches differ from the expected medical treatment:

… the answer isn’t [just] putting more drugs that have crazy side effects - potential side effects - in your body; it can be something else. [FG6:FP1].

Participants also wanted content that gave advice about exercise and activity. Managing energy expenditure and giving oneself permission NOT to do a task, is as important as being moderately active, because of the benefits on fatigue, on mental well-being, and on general physical fitness:

Actually, going [to the gym] and trying to be strong when I’m able to be strong helps for when I’m not feeling so great. And if you do have operations, the stronger you are before you have them, the more you recover afterwards. And when you’re feeling good and you do the gym, you feel even better afterwards. You’re not going to feel amazing, but you do feel a bit better, you’ve got a bit more energy. [FG3:MP1]

Alongside distinct “interventions” such as those described above, participants also stressed the value of peer support and learning from others who are “in the same boat”:

Patient profiles, different people who [manage] just through diet and just through medication and surgery - like an insight into each route and just answering questions about it in terms of: now what is your diet? What do you avoid? Has it made a big difference? … because those are questions that I’ve got myself. Even surgery, you know … what’s it like living with a stoma? [FG1:MP1]

Participants emphasized that there needed to be balanced in these stories—positive and negative experiences—not just the “scare stories of surgery and stomas” [FG1:FP2].

Other recommended content included providing ways of connecting with other people living with IBD:

If there was some kind of way of [having] a map and for people that opt into it, linking up to people who live locally to you, because you’ve found them on this map of people in your area who have similar conditions. So you can go out for tea, you can finally let your hair down with someone who gets it, who really, really, gets it’ [FG3:FP3]

This participant explained that such a map could also act as a mentoring or buddy system for newly diagnosed patients, as well as giving people the freedom to talk “without having to explain or censor.”

Access to a range of useful information would enable people to understand what they could do to gain control:

… [the self-management intervention] would be really, really helpful and I think there has been a lot of advances but having somewhere that’s got lots of information about lots of different elements and just thinking about all the ways that you can self-manage rather than just what the hospital will tell you [FG1:FP3]

To address the fact that any intervention could not contain all information that might be beneficial, participants recommended having a remote helpdesk or signposting function which could direct people to other useful external sources. This included directing people toward thriving online communities such as IBD charity chatrooms, Facebook groups, Twitter, or other social media platforms, as well as more formal information resources:

If somebody was looking for something about their drugs, it would point them to the right bit of CCUK (Crohn’s and Colitis UK) or NHS (National Health Service) or something like that where there’d be the correct information [FG3:FP1]

Access to Professional Support

Participants suggested including hints and tips for navigating health services to help people get the support they needed from healthcare professionals, including the GP (community physician):

… if you speak to the practice manager and say, “OK, what can you do for me as someone with Crohn’s that has a long-term health condition?” … nine times out of ten they’ll sit down with you and say, “We can offer you longer appointments, we can offer you emergency phone appointments when you need them if you can’t get to your consultant” [FG1:FP3]

Participants wanted the self-management intervention to encourage patients to connect with and draw on the expertise of the IBD Clinical Nurse Specialists, although they also acknowledged that not everyone had access to this service.

Participants also wanted their clinical team to be able to connect electronically to any symptom tracking information that they could record in the self-management intervention: “I guess the ideal solution would be that it was plugged into your medical team, so your nurse and your consultant have access to it. So that if you are starting to deteriorate, they can say “We can see that you are struggling or that you might need some support, do you want to come in?” - so that everybody is aware of what your symptoms are.” [FG1:FP2].

Discussion

There is previous robust evidence on the incidence and prevalence of the symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency associated with IBD [6, 28, 29] but these are typically considered separately. Participants in our earlier study [23] reported that symptoms arise not necessarily equally, but often simultaneously, while those in this study report that the techniques they use to manage one symptom, can benefit the other two. Current participants wanted this inter-relationship acknowledged and stressed that the key to self-management in IBD was working out what works “for you.” They recommended providing core practical tips for managing symptoms, so that patients can develop strategies to help themselves sooner rather than later in their illness experience. They also stressed the importance of addressing the psychological impact of IBD and furnishing people with ways of improving their mental health as well as benefitting their physical health.

Participants wanted the planned self-management intervention should have a function to enable tracking of symptoms. Key to the success of this technique is that the participant doesn’t simply record the facts but notices the pattern—and changes behaviors accordingly. By using a tracker to spot any deterioration early, the patient can respond promptly, and follow-up with their IBD clinical team if necessary.

The role of diet in IBD is widely researched and debated [30,31,32,33]. Like many patients, our participants were very interested in the influence of diet on symptoms of IBD; while they appreciated that there is no generic answer and dietary intolerances and needs are highly individual and can change over time, they also suggested the benefits of recording dietary intake and tracking the effects over time. Keeping a dietary diary, again enables the patient to identify any potential relationship between what they eat, and any change in symptoms. The technique has proven effective among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome [34], and there are numerous downloadable apps to help patients self-manage. There is potential for the online self-management program, informed by this data, to signpost patients to readily available resources to support dietary self-management in IBD [35, 36].

Patients with IBD often find it difficult to build support networks, because of the challenges of revealing a condition which others often find distasteful [37, 38], even though there are clear benefits to doing so [39,40,41]. As has been demonstrated across other chronic conditions and illness challenges [42,43,44], social support is beneficial for maintaining well-being, and can facilitate adjustment to chronic illness [45, 46]. Creating opportunities within a self-management intervention to connect with and have opportunity to talk to others with the same diagnosis who would understand the situation, as well as providing links to external existing support groups and charities, may therefore be beneficial.

Patients both want and need relevant self-management information, from the point of diagnosis. It helps them understand their disease, and gain control over their illness. Yet patients may need help in re-framing their ways of thinking, to be able to make best use of this information. The intervention model being developed as a result of this and previous preparatory work [23] uses cognitive behavioral techniques [47] to help individuals avoid catastrophizing thoughts and reduce anxiety [48], and make self-care decisions based on pragmatic advice and information.

Given recent alterations in the delivery of and access to health care precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, many of which may become incorporated into routine practice post-pandemic across health services worldwide [49, 50], the provision of online self-management resources may be very timely. If successful, there is potential to adapt the intervention model for those living with other chronic conditions, including long COVID.

Strengths and Limitations

Study participants were self-selected; others who did not or were not able to take part may have offered different recommendations. Of those who did take part, many reported the symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency incontinence to be “quite” or “very” troublesome (Table 2), indicating that they had robust experience to draw on when contributing. Participants who mentioned functionality were unanimous about the way they wanted it to work. Data analysis procedures were thorough, adding credibility to the findings. Recruiting from clinic and community sources increased the representativeness of the sample.

Conclusion

Individuals with IBD have a range of techniques they use to self-manage the three symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency/incontinence that affect their illness experience in IBD. They report that techniques to manage can ease another. They were decisive about the practical features they wanted in an online self-management intervention, clearly requesting that it should work across multiple platforms, operate smoothly, and be easy to engage with and use. They offered recommendations on ways of coping with the three symptoms of fatigue, pain, and urgency, to inform intervention content, as well as addressing related issues such as mental well-being, and stress-reduction options. They also identified that interventions to address fatigue, such as mild to moderate exercise, had a beneficial impact on mental well-being. There was enthusiastic support for symptom and diet tracking functions, and suggestions to help people find their way to other sources of support and advice. Based on this input from patients, and existing intervention development literature, the IBD-BOOST online self-management intervention has now been developed and is undergoing testing in a randomized controlled trial [51]. There is potential, if effective, for roll-out across other chronic illness patient groups.

Data availability

The qualitative data produced during this work are held at King’s College London, England; study participants gave consent for their data to only to be used again by these researchers/authors in any future work. Consequently, it has not been archived in a public repository.

References

Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007;369:1627–1640.

Zhou N, Chen WX, Chen SH, Xu CF, Li YM. Inflammatory bowel disease unclassified. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:280–286.

Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54.

Czuber-Dochan W, Ream E, Norton C. Review article: description and management of fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:505–516.

Lönnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, Hommes D, Bell C, Avedano L. IBD and health-related quality of life—discovering the true impact. J Crohn’s Colitis 2014;8:1281–1286.

Norton C, Dibley LB, Bassett P. Faecal incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease: associations and effect on quality of life. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2013;7:e302–e311.

Bajorek Z, Summers K, Bevan S. Working well: promoting job and career opportunities for those with IBD. The Work Foundation; 2015. www.theworkfoundation.com.

Czuber-Dochan W, Norton C, Bredin F, Darvell M, Nathan I, Terry H. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of fatigue experienced by people with IBD. J Crohn’s Colitis 2014;8:835–844.

Dibley L, Norton C. Experiences of fecal incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: self-reported experiences among a community sample. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1450–1462.

Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:177–187.

Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7.

Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2013;119:239–243.

Dineen-Griffin S, Garcia-Cardenas V, Williams K, Benrimoj SI. Helping patients help themselves: a systematic review of self-management support strategies in primary health care practice. PLoS ONE 2019;14:e0220116–e0220116.

Norton C, Hart A, Taylor S, et al. Living well with inflammatory bowel disease: optimising management of symptoms of fatigue, abdominal pain, and faecal urgency/incontinence via tailored online self-management: the IBD-BOOST programme (NIHR-PGfAR: RP-PG-0216–20001). https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/RP-PG-0216-20001

Stebbins R. Exploratory research in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001.

Bradshaw C, Atkinson S, Doody O. Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2017;4:2333393617742282. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617742282.

Sweeney L, Moss-Morris R, Czuber-Dochan W, Belotti L, Kabeli Z, Norton C. ‘It’s about willpower in the end. You’ve got to keep going’: a qualitative study exploring the experience of pain in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Pain. 2019;13:201–213.

Elbers S, Wittink H, Pool JJM, Smeets RJEM. The effectiveness of generic self-management interventions for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain on physical function, self-efficacy, pain intensity and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 2018;22:1577–1596.

Conley S, Redeker N. A systematic review of self-management interventions for inflammatory bowel disease. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48:118–127.

Moss-Morris R, McCrone P, Yardley L, van Kessel K, Wills G, Dennison L. A pilot randomised controlled trial of an Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy self-management programme (MS Invigor8) for multiple sclerosis fatigue. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:415–421.

Srivastava A, Thomson SB. Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. JOAGG 2009;4:72–79.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117.

Dibley L, Khoshoba B, Artom M, Van Loo V, Sweeney L, Syred J et al. Patient strategies for managing the vicious cycle of fatigue, pain, and urgency in inflammatory bowel disease: impact, planning and support. Dig Dis Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06698-1.

Spencer L, Ritchie J, O’Connor W. Analysis: practices, principles and processes. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, eds. London: Sage Publications Inc; 2003; 199–262.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook, 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.; 2018; 380.

Cypress BS. Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2017;36:253–263.

Van Langenberg DR, Gibson PR. Systematic review: fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:131–143.

Zeitz J, Ak M, Müller-Mottet S, Scharl S, Biedermann L, Fournier N et al. Pain in IBD patients: very frequent and frequently insufficiently taken into account. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156666.

de Vries JHM, Dijkhuizen M, Tap P, Witteman BJM. Patient’s dietary beliefs and behaviours in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2019;37:131–139.

Holt DQ, Strauss BJ, Moore GT. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their treating clinicians have different views regarding diet. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30:66–72.

Guida L, Di Giorgio FM, Busacca A, Carrozza L, Ciminnisi S, Almasio PL et al. Perception of the role of food and dietary modifications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: impact on lifestyle. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–12.

Limdi JK. Dietary practices and inflammatory bowel disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37:284–292.

Wright-McNaughton M, Ten Bokkel Huinink S, Frampton CMA, McCombie AM, Talley NJ, Skidmore PML et al. Measuring diet intake and gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: validation of the food and symptom times diary. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10:e00103.

Crohn’s and Colitis UK. Food and IBD. https://www.crohnsandcolitis.org.uk/about-crohns-and-colitis/publications/food. Accessed 29 Apr 2021.

Ampersand Health. Digital therapies for inflammatory conditions. https://ampersandhealth.co.uk/myibdcare/. Accessed 29 Apr 2021.

Dibley L, Norton C, Whitehead E. The experience of stigma in inflammatory bowel disease: an interpretive (hermeneutic) phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:838–851.

Taft TH, Keefer L, Leonhard C, Nealon-Woods M. Impact of perceived stigma on inflammatory bowel disease patient outcomes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1224–1232.

Moskovitz DN, Maunder RG, Cohen Z, McLeod RS, MacRae H. Coping behavior and social support contribute independently to quality of life after surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:517–521.

Fröhlich DO. Support often outweighs stigma for people with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2014;37:126–136.

Maguire R, Hanly P, Maguire P. Living well with chronic illness: how social support, loneliness and psychological appraisals relate to well-being in a population-based European sample. J Health Psychol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319883923.

Rosland AM, Heisler M, Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2012;35:221–239.

Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav 2003;30:170–195.

Strom JL, Egede LE. The impact of social support on outcomes in adult patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Curr Diabetes Rep 2012;12:769–781.

Dibb B, Yardley L. How does social comparison within a self-help group influence adjustment to chronic illness? A longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1602–1613.

Karabulut HK, Dinç L, Karadag A. Effects of planned group interactions on the social adaptation of individuals with an intestinal stoma: a quantitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:2800–2813.

Craske M. Cognitive behavioral therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009.

Wells A. Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: a practice manual and conceptual guide, Chichester: Wiley; 1997; 314.

Marlow J, O’Shaughnessy J, Keogh B, Chaturvedi N. Learning from a pandemic: how the post-covid NHS can reach its full potential. BMJ 2020;371:3867. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3867.

Sorenson C, Japinga M, Crook H, McClellan M. Building a better health care system post-Covid-19: steps for reducing low-value and wasteful care. NEJM Catal. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0368.

Norton C. Supported online self-management for symptoms of fatigue, pain and urgency/incontinence in people with inflammatory bowel disease: the IBD-BOOST trial. BMC ISRCTN Regist. 2019; https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN71618461.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Crohn’s and Colitis UK, and colleagues at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust, St Mark’s Hospital Harrow, and Salford Royal NHS Trust for their assistance with organizing and hosting the original focus groups.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) Programme [Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0216-20001]. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CN, LD, and RM-M conceived and designed the study which forms the first part of a program of research; JS, LD, MA, and SW collected the data; JB, JS, KS, MA, and SF carried out data analysis and supervised by CN and LD; JB, KS, and SF wrote the first draft of the manuscript before handing over to LD; all authors have reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statement

The UK National Research Ethics Service (Wales Research Ethics Committee 4; Ref: 17/WA/0349) gave approval for the study. Participants were reimbursed for expenses incurred when attending the focus groups or a face-to-face interview. Interested respondents received the Participant Information Sheet. Focus group participants agreed to a group consent statement, and all focus group and interview participants provided written informed consent immediately before data collection.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Artom is now at NHS Digital; Jonathan Syred is now working in primary school education.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fawson, S., Dibley, L., Smith, K. et al. Developing an Online Program for Self-Management of Fatigue, Pain, and Urgency in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Patients’ Needs and Wants. Dig Dis Sci 67, 2813–2826 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07109-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-07109-9