The most common way corrupt officials hide money is by stashing it in an “offshore vehicle.” The “vehicle” will be a corporation, trust, or other legal person. It is termed “offshore” because it will be organized under the laws of another country. Stolen funds and assets purchased with them can then be listed in the name of the offshore entity.

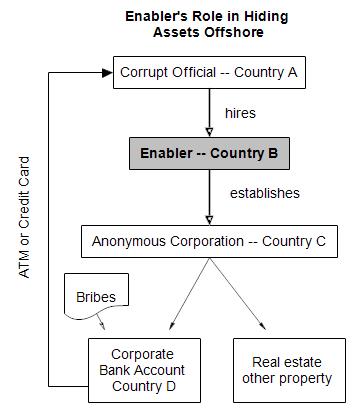

To create an offshore vehicle, the official will turn to someone with expertise in creating offshore entities and disguising their ownership: a lawyer, accountant or other professional who knows corporate and trust law and how to use it to hide the owner’s identity. The anticorruption community has dubbed these intermediaries “enablers,” for they enable corruption by providing corrupt officials with a way to enjoy the proceeds of their corruption. A typical scheme is shown in the diagram below.

An official in country A wanting to hide assets first hires an enabler. Although the enabler could be a professional in country A, hiring one located in another state makes it that much harder for local authorities to uncover wrongdoing. The enabler, shown in the diagram as located in country B (most often a wealthy country), then creates the offshore vehicle. The enabler could have created the vehicle, in this case a corporation, in the enabler’s own country.

But again, to make it harder for investigators to trace assets, the enabler will usually form the vehicle in still another country, here labelled C. As the diagram shows, to further frustrate efforts to track money flows the anonymous corporation (or shell or letter-box company — the terminology differs in different jurisdictions) will then open a bank account and buy real estate and perhaps art works or other personal or moveable property in still a fourth country.

The enabler will know which countries allow creation of an anonymous corporation, one where the identity of the actual, or beneficial, owner need not be revealed. (An ever changing list thanks to ongoing reform efforts.) The enabler will also have contacts with bankers willing to open a corporate account in the corporation’s name without asking who really owns the corporation. The enabler will too often know real estate agents and antique and fine arts dealers who will be happy to sell the corporation expensive properties and — for a hefty commission or fat markup — not be too curious about the corporation’s owner.

As the diagram shows, for a corrupt official having control of a corporate bank account is especially advantageous. Not only does the official have a safe place to hide what they have already stolen, it provides a way to safely steal more by providing future bribe payers a way to pay bribes — directly into the official’s corporate account. Once the money is in the account, it can be funneled back to the official and family members through a credit or ATM card issued in the corporation’s name.

A critical step in curbing corruption is cracking down on enablers. If those tempted to take bribes or embezzle public funds had no way to hide what they stole, they would be less likely to rob the public. Here are three steps that will help put enablers out of business.

1. MAKE ALL ENABLERS SUBJECT TO THE ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING LAWS

Money laundering is the concealment of the origins of illegally obtained money. UNCAC requires states parties to criminalize it, and all but a few have. Anyone helping a public official hide stolen money therefore commits the crime of money laundering. But in many states enablers do not fear prosecution. If their actions are discovered, they will claim they did not know the assets were stolen. They will say that they were simply asked to establish a corporation, buy real estate, or conduct other transactions with a client’s assets. They had no idea the assets were stolen. A criminal conviction requires defendants know their actions were wrong, and enablers can take measures to make it almost impossible to show they knew where the assets came from.

For almost two decades, the Financial Action Task Force has urged the enactment of legislation to end this defense. The recommended legislation would require professionals to carefully investigate, in money laundering terms conduct “enhanced due diligence” on, the origins of funds a current or former government official, a family member or close associate asked the professional to handle. Making professionals scrutinize the assets of these “politically exposed persons,” as the anti-money laundering laws term them, would prevent enablers from asserting the lack of knowledge defense. The law would require them to know where the funds came from and sanction them for not knowing. To further increase the risk of prosecution for enabling, FATF also recommends that professionals be required by law to continuously monitor transactions they conduct for a politically exposed person and to report any that appear suspicious.

The enhanced due diligence recommendation is contained in FATF Recommendation 22 and the suspicious transaction one in Recommendation 23. The adoption of FATF recommendations depends upon a government’s commitment and willingness to curb money laundering. That compliance is subject to periodical review by peer governments. The theory is that the publicity generated when a review shows a country is not complying with a recommendation will generate international and domestic pressure on the government to comply.

Unfortunately, in the case of Recommendations 22 and 23 the theory has not proven out. Four G20 members – Australia, Canada, the People’s Republic of China, and the United States – have refused to comply with either recommendation (here). FATF data show another 48 jurisdictions, listed below, have only partially complied with either Recommendation 22 or 23 or both. Partial compliance can mean that an important profession – lawyers in Denmark, real estate agents in Singapore – is not covered. It can also mean no firm or individual has ever reported a suspicious transaction or that the sanctions for failing to report are mild.

Until all states fully adhere to FATF Recommendations 22 and 23, corrupt officials will be able to find someone willing to act as an enabler, to be an accomplice to their theft of government assets. The United Nations, the OECD, governments, and international and domestic pressure groups should make make full compliance by all states with FATF Recommendations 22 and 23 a top priority.

2. MAKE ASSET HIDING A SERIOUS CRIME

When incorporating Recommendations 22 and 23 into their domestic law, governments should ensure the penalties for a violation reflect the seriousness of the offense. Assets are too often stolen from the world’s poorest nations, depriving their governments of the resources required to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals and so meet the needs of their most vulnerable citizens. As accomplices, those who hide these assets are as responsible for the resulting harm as the government officials who betrayed the public trust.

Violations of Recommendations 22 and 23 are not the only enabling-offenses that should carry hefty fines and long prison sentences. Falsely reporting the beneficial owner of a corporation or other offshore vehicle or failing to disclose that an individual is a director or manager of a vehicle facilitates asset hiding should be as well. These actions again facilitate the looting of assets from the world’s poorest nations.

Those who hide corrupt official’s assets reap large rewards for little work, a powerful incentive for some to join the ranks of enablers. The penalties for enabling should be substantial enough to change the calculus.

3. DENY PROFESSIONAL PRIVILEGE PROTECTION TO INVESTMENT TRANSACTIONS

All United Nations Member States protect a client’s communications with a lawyer, notary, or other legal professional when the communication relates to a judicial proceeding or the legal aspects of a transaction. Lawyers are barred — in some countries by statute and in others by court decisions — from disclosing what their client tells them and the advice they provide. While there are sound reasons for this legal privilege, it open to abuse it. One all too common is its use to keep from disclosing routine, non-legal work – creating a corporation or purchasing real estate – to authorities.

Vaguely drafted statutes or broadly worded judicial decisions allow lawyer-enablers to get away with such abuses. Governments should be sure enabler lawyers and notaries cannot, that domestic law does not permit routine, non-legal work to be shielded from disclosure by the legal professional privilege. FATF Recommendation 22 reflects a widely-shared, international consensus that there are certain tasks clients have legal professionals perform which should not be subject to legal privilege They are:

– forming a corporation or other legal person;

– serving as a director or secretary of a company, a partner of a partnership, or a similar position in relation to any other legal person;

– performing the duties of a trustee of an express trust or the equivalent function for another form of legal person;

– acting a nominee shareholder for another person;

– arranging for another person to act in one of the roles identified above; or

– providing a registered office; business address or accommodation, correspondence or administrative address for a company, a partnership or any other legal person or arrangement;

The abuse of legal privilege disclosed by the International Consortium of Journalists in the Panama Papers (here), the willingness of so many lawyers to respond positively to inquiries about asset hiding schemes, and the alacrity with which numerous prestigious New York lawyers responded to the Global Witness ruse to help a corrupt minister conceal assets show that professional self-regulation is wanting. All states should enact legislation denying professional privilege for financial or administrative work.

(This post is a revised version of section IV.C of “Recommendations for Accelerating and Streamlining the Return of Assets Stolen by Corrupt Public Officials,” a paper co-authored with Fatima Kanji for the High-Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity for Achieving the 2030 Agenda Financing for Sustainable Development. The full text is here.)

Pingback: Episode 230 – the $20,000 a Day Lawyer edition | The Compliance Podcast Network

Pingback: This Week in FCPA-Episode 230 – the $20,000 a Day Lawyer edition - Compliance ReportCompliance Report