ENDOCRINOLOGY AND DIABETOLOGY

SPECIAL FOCUS ON OBESITY

Addressing stigma, new international guidelines, and the latest evidencebased treatment approaches

Full coverage of EASD 2020

CLINICAL ARTICLES ON osteoporosis, PCOS, thyroid disorders, and diabetic retinopathy

Type 1 and 2

DIABETES

The latest drug therapies, monitoring technologies, and HSE management in primary care

VOL 6 ISSUE 8 2020

Surviving and thriving during Covid-19

Welcome to the latest edition of Update Endocrinology and Diabetology.

As health services continue to grapple with providing care in the ‘new normal’ caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, there is rising concern about missed opportunities and early warning signs being ignored in people with chronic diseases such as diabetes.

After the initial wave and early lockdown, hospital and community diabetes services began gradually resuming and scaling up delivery of care and reaching out to patients in need of check-ups and intervention, but the second wave has quickly brought fresh challenges and patients understandably remain reluctant to seek help for what might seem like minor issues.

Commenting on this worrying development recently, Dr Anna Clarke, Diabetes Ireland, said: “We know people are delaying contacting GPs and hospital diabetes teams in the belief that they are helping those professionals cope with the current Covid-19 burden, but in doing so may be risking their own health as their problem escalates. It is vital to seek medical attention early and be treated and reassured.”

In August the HSE and Diabetes Ireland launched an awareness campaign urging people with concerns about their diabetes to seek medical advice from their pharmacist, GP or hospital diabetes team and reassured them that diabetes services had resumed and are continuing despite the challenges of providing care while dealing with Covid-19.

In an interview in this issue of Update, Prof Sean Dinneen, Consultant Endocrinologist and Clinical Lead, HSE National Clinical Programme for Diabetes, highlights the importance of patients continuing to seek help despite the current challenges: “We are in a very fluid environment and diabetes services are experiencing significant capacity issues at present as the health service deals with this pandemic. However, it must be stressed that delays in seeking medical attention often results in additional care being needed.”

As he points out: “The Covid-19 pandemic presented our health service with a set of unprecedented circumstances resulting in disruption to the delivery of non-Covid care, including routine diabetes care. The remarkable work carried out by healthcare teams across the country and the support, co-operation, and understanding of patients, service users and families during the recent first phase of the Covid-19 response is very much appreciated by all in the health service.”

Throughout the pandemic, diabetes and endocrinology healthcare providers have also worked hard to adapt to remotely support and empower people in selfmanaging their conditions at home. Maintaining this self-management will continue to improve quality-of-life and reduce the impact on health and the likelihood of complications, and telehealth solutions are being supported by the HSE to continue and evolve.

Meanwhile, the Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (IrSPEN) has also cautioned that patients with obesity, who are at higher risk of complications from Covid-19, need equal access to treatments during the pandemic and must not have their surgeries and other treatments indefinitely delayed.

To help manage this challenge, obesity consultants from around the world,

including Ireland, have together published guidance on prioritising access to surgery and treatments for those with obesity and associated diabetes, the details of which are featured on page 11.

This issue has a special focus on obesity, looking at the latest knowledge and addressing stigma, with expert articles on evidencebased treatment approaches including drug therapies, surgery, and specialist diets.

There are also a number of in-depth clinical articles on managing type 1 and type 2 diabetes, including the latest drug therapies, disease-monitoring technologies, closed loop insulin delivery, and an overview of the HSE’s chronic disease management programme for diabetes in primary care.

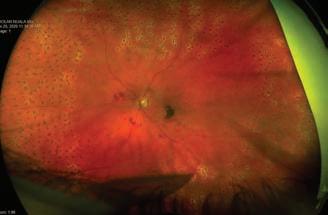

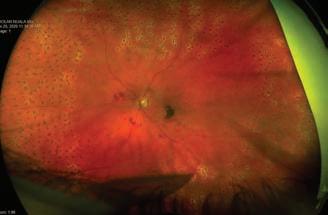

In addition, there is a comprehensive overview of diabetes and the kidney and how Covid-19 has impacted these patients, a very interesting case study article on a rare form of diabetic retinopathy from Diabetic RetinaScreen, as well as practical expert overviews of common thyroid disorders and osteoporosis, and management approaches for PCOS.

Conference wise, there is a round-up of the most topical research presented at the recent 2020 European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) meeting, held virtually for the first time this year.

So all in all, a packed edition that should hopefully prove interesting and useful to all our readers.

Thank you to our expert contributors for taking the time to share their knowledge and advice for the betterment of patient care.

We always welcome new contributors and suggestions for future content, as well as any feedback on our content to-date. Please contact me at priscilla@mindo.ie if you wish to comment or contribute an article. ■

1 Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology

A message from Priscilla Lynch, Editor

24 Changing the landscape for community-based type 2 diabetes care in Ireland

Osteoporosis: The silent

32 Diabetes and the kidney in 2020; glimmers of hope in the face

Editor Priscilla Lynch priscilla@mindo.ie

Sub-editor Emer Keogh emer@greenx.ie

Creative Director Laura Kenny laura@greenx.ie

Advertisements Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

Administration Daiva Maciunaite daiva@greenx.ie

Update is published by GreenCross Publishing Ltd, Top Floor, 111 Rathmines Road Lower, Dublin 6 Tel +353 (0)1 441 0024 greencrosspublishing.ie

© Copyright GreenCross Publishing Ltd 2020

The contents of Update are protected by copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means – electronic, mechanical or photocopy recording or otherwise – whole or in part, in any form whatsoever for advertising or promotional purposes without the prior written permission of the editor or publisher.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in Update are not necessarily those of the publishers, editor or editorial advisory board. While the publishers, editor and editorial advisory board have taken every care with regard to accuracy of editorial and advertisement contributions, they cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions contained.

GreenCross Publishing is owned by Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

Contents 2 03

Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2020 Meeting report 06 Irish diabetes research: Insulin pump therapy uptake low in Ireland 08 Interview with Prof Sean Dineen, HSE Clinical Lead for Diabetes 10 Is obesity really a disease? 12 Advances in diabetes technology 14 Closed loop insulin delivery in type 1 diabetes mellitus 18 The latest treatment approaches in diabetes 21 Diabetes and the new HSE chronic disease management programme

European Association for the

26

36

2 diabetes and obesity: How to treat a twin pandemic 40 Obesity in adults – a new clinical practice guideline from Obesity Canada 44 Common thyroid disorders: An overview 49 Managing polycystic ovary syndrome 51 Diabetic retinopathy: An unusual case report

disease

of a global pandemic

Treating type

AUTHOR: Priscilla Lynch provides a round-up of some of the most topical research presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), held online this year from 21-25 September 2020

A new modelling study presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) suggests that the average person with type one diabetes (T1DM) will live almost eight years less than the average person in the general population without diabetes, while those with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) will live almost two years less.

For their analysis, the authors used mortality data from the UK National Diabetes Audit (NDA) for 2015-16, and the O ce for National Statistics (ONS) published for 2015-17. The researchers took data from 6,165 general practices supporting 41.3 million people of whom 217,000 were on T1DM register and 2.50 million on T2DM register.

In their model, the authors applied relative NDA mortality rates to population rates for each age/sex, and then calculated the future life expectancy for T1DM/T2DM/ non-DM populations. The di erence between total life expectancy for the total reported populations by age and gender of T1DM and T2DM and an equivalent

population with non-DM gave the total ‘lost life years’ (LLY).

In the model the ‘average’ person with T1DM (age 42.8 years) has a life expectancy of 32.6 years (living to 75.4 years), compared to 40.2 years (living to 83.0 years) in the equivalent age non-diabetic population, corresponding to a mean LLY of 7.6 for the average person with T1DM.

The model showed the ‘average’ person with T2DM (age 65.4 years) has a life expectancy of 18.6 years (living to 84.0 years) compared to the 20.3 years (living to 85.7 years) for the equivalent non-diabetic population, corresponding to LLY of 1.7 years for the average person with T2DM.

Compared with the average LLY for men, the average LLY/person were 21 per cent higher for women with T1DM and 45 per cent higher for women with T2DM.

The authors also add that the NDA reports that 70 per cent of patients with T1DM and 33 per cent of patients with T2DM had a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) higher than 58mmol/

mol, so were at higher risk of poor outcomes.

By allocating total LLY to the future life expectancy of both T1DM and T2DM at-risk group, the model shows that each year that a person with either type of diabetes spends with HbA1c >58mmol/mol could shorten their life by 100 days. The authors said:

“Knowledge of this may act as an incentive for clinicians to ensure that all people are on the best therapy to keep their blood sugar in the target range, and for those people to engage more strongly with their therapy and lifestyle recommendations.”

The authors mention some limitations to their study, namely that is used nationallevel mortality data and not GP practicelevel data. Also, it is likely that other factors contribute such as smoking, inactivity, overweight, hypertension and taking of statins.

These will be the subject of a future full analysis with general practice-level data. However, the authors say it is likely that the HbA1c level will remain a strong independent determinant of mortality. ■

Study shows that analysing tears could allow for non-invasive diabetes blood glucose monitoring

A new study presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of EASD shows that analysing the tears of people with diabetes could be a potential method to monitor their blood glucose levels without the need for invasive alternatives that rely on blood testing.

Previous studies of glucose levels in tears have shown that they correspond well to the amount of glucose in the blood. In this research, the Japanese team focused on glycoalbumin (GA) levels, which reflect an average of blood glucose levels over the preceding two weeks; and investigated the

correlation between GA level in tears and those in blood.

A total 100 subjects with diabetes were recruited for the study, and samples of both tears and blood were collected for analysis. Samples from 99 of the 100 participants were successfully measured, and significant correlation was found between GA levels in tears and those in blood. Statistical analysis showed that this correlation was maintained even after adjustment for age, gender, kidney function, and obesity.

Given the strong correlation between GA levels in tears with those in the blood, the team suggest that it has potential to be used as a method of non-invasive diabetes monitoring. They note that since the GA value is expressed as a ratio, the concentration or dilution of tears is not thought to influence the measurement.

The authors said: “In the future, we plan to optimise measurement conditions and develop measurement equipment, and to verify the e ectiveness and usefulness of diabetes monitoring methods.” ■

3 Endocrinology and Diabetology | Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020

Study suggests average person with type 1 diabetes will live almost eight years less and those with type 2 diabetes almost two years less

What have we learned from Covid-19 in persons with type 1 diabetes?

While diabetes is established as a risk factor for severe SARS-CoV2 infection several important specific aspects need to be considered for people with type 1 diabetes. In contrast to older persons with diabetes, children, adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes are not at risk for unfavourable outcomes.

However, in a special session on Covid-19 at this year’s Annual Meeting of EASD, Prof Catarina Limbert of the University Centre of Central Lisbon and Hospital Dona Estefania, Lisbon, Portugal, presented new review of viruses that are known to contribute to the new onset of type 1 diabetes and new evidence that SARS-CoV2 infection needs to be added to this list.

“Until now, larger multicentre studies did not find a rise in the number of new cases during the pandemic months compared to the same period in years before,” she explained. “Nevertheless, the Covid-19 crisis has increased the severity at onset of type 1 diabetes with a doubling of people being admitted with diabetic ketoacidosis during the lockdown.”

A population study of 23,804 Covid-19 related deaths in England during 1 March - 1 May 2020 revealed that the odds of dying in hospital with Covid-19 was higher in people with type 1 diabetes (3.5 times) compared to type 2 diabetes (two times). However, the average age at death was 78 years in type 2 diabetes and 72 in type 1 diabetes. It appears, that in type 1 diabetes, only older people aged over 50 years with longer duration of the disease (80 per cent with more than 15 years of disease) and worse glucose control (glycated haemoglobin/ HbA1c >10 per cent) are at higher risk of severe clinical outcomes of Covid-19.

Moreover, according to an early report by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from the US with data from 149, 082 Covid-19 cases, only 1.7 per cent were among children <18 years. Diabetes was not among the comorbidities, indicating that with or without diabetes, young people are coping better with Covid-19 infection. Di erences in the anatomy, epidemiology and gene expressions are some of the reasons for the low prevalence of Covid-19 infection in children.

In contrast to challenges related to disease severity and outcomes in type 1 diabetes, the pandemic also o ers opportunities for improving diabetes care management, Prof Limbert said.

“The Covid-19 crisis was the booster shot to put telemedicine into practice. During the lockdown period, healthcare delivery had to adapt and make a sudden transition to remote care. In paediatric diabetes, digital revolution in type 1 diabetes management already started many decades ago with pumps and now extended to integration of sensors, automated insulin delivery or dosage advisors.

“The need to upload the data for a meaningful telemedicine consultation has motivated families to become more involved with digital diabetes data. The use of remote healthcare promoted autonomy of both young people and their parents in interpreting the data and making decisions. Thus, challenges of Covid-19 turned out to be an opportunity for empowerment of people with type1 diabetes.” ■

Study reveals type 2 diabetes remission can restore pancreas size and shape

In 2019, research revealed that achieving remission of type 2 diabetes by intensive weight loss can restore the insulinproducing capacity of the pancreas to levels similar to those in people who have never been diagnosed with the condition. Now, new research presented at the 2020 Annual Meeting of EASD demonstrates for the first time that reversing type 2 diabetes can also restore the pancreas to a normal size and shape.

“Our previous research demonstrated the return to long-term normal glucose control, but some experts continue to claim that this is merely ‘well controlled diabetes’ despite our demonstration of a return to normal insulin production by the pancreas. However, our new findings of

major change in the size and shape of the pancreas are convincing evidence of return to the normal state,” said Prof Roy Taylor from Newcastle University, UK, who led the research.

Previous imaging studies have shown reduced size and abnormal shape of the pancreas in people with type 2 diabetes. But whether these abnormalities resulted from, rather than led to, the disease state was unknown until now.

In the study, 64 participants from the landmark Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) and 64 age-, sex-, and weight-matched controls without type 2 diabetes were measured over two years for pancreas volume and fat levels, and

irregularity of pancreas borders using a special MRI scan. Beta cell function was also recorded. Responders were classified as achieving a glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of less than 6.5 per cent and fasting blood glucose of less than 7.0mmol/l, o all medications.

At the start of the study, average pancreas volume was 20 per cent smaller (64cm3 vs 80cm3), and pancreas borders more irregular, in people with diabetes compared with controls without diabetes.

After five months of weight loss, pancreas volume was unchanged irrespective of remission (63cm3 to 64cm3 for responders and 59cm3 to 60cm3 in non-responders). However, after two years, the pancreas had

Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology 4

grown on average by around one-fifth in size (from 63cm3 to 76cm3) in responders compared with around a twelfth (from 59cm3 to 64cm3) in those who did not.

In addition, responders lost a significant amount of fat from their pancreas (1.6 per cent) compared with non-responders (around 0.5 per cent) over the study period, and achieved normal pancreas borders.

Similarly, only responders showed early and

sustained improvement in beta-cell function. After five months of weight loss, the amount of insulin being made by responders increased and was maintained at two years, but there was no change in non-responders.

“Our findings provide proof of the link between the main tissue of the pancreas which makes digestive juices and the much smaller tissue which makes insulin, and open up possibilities of being able to predict future onset of type 2 diabetes by

scanning the pancreas,” said Prof Taylor.

“All our research has been focused on type 2 diabetes which has developed within the last six years. Although some people with much longer duration diabetes can achieve remission, it is clear that the insulin producing cells become less and less able to recover as time passes. We need to understand exactly why this is and find ways to restore function in long duration type 2 diabetes.” ■

Special safety protocol successfully allowed pilots with diabetes to work

A new study presented at this year’s Annual Meeting of EASD shows that the introduction of a new safety protocol has successfully enabled people with insulintreated diabetes to work as commercial pilots, and could potentially allow individuals with the condition to perform other ‘safety-critical’ jobs such as bus drivers or maritime workers.

The study, conducted by Dr Gillian Garden and colleagues at the Department of Metabolism and Ageing, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, as well as researchers and industry professionals from universities and civil aviation authorities in the UK, Ireland, and Austria, evaluated the performance and safety impact of a new protocol that enabled certificated pilots with insulin-treated diabetes to fly commercial aircraft for the first time.

The risk of hypoglycaemia in people with insulin-treated diabetes has for many years debarred them from working in certain ‘safety-critical’ jobs, including flying commercial airliners.

The UK, together with Ireland and Austria, introduced a ground-breaking safety protocol for certificated pilots with insulintreated diabetes, and now have the largest number of people in the world with the condition working as commercial pilots. Anyone with diabetes is subjected to strict oversight including glucose monitoring

during duty periods, and frequent clinical health reviews.

The team performed an observational study of 49 pilots with insulin-treated diabetes who had been granted medical certification to fly commercial (Class 1 certificate) and non-commercial (Class 2 certificate) aircraft. Clinical details, pre and in-flight (hourly and 30 minutes pre-landing) blood glucose values were compared with the protocolspecified ranges: ‘Green’ (5-15mmol/L), ‘amber’ (low 4-4.9mmol/L, high 15.1-20mmol/L), and ‘red’ (low <4.0mmol/L, high >20.0mmol/L).

In the case of a ‘red’ low reading for example, the pilot is required to immediately hand over duties to the co-pilot or, if flying solo, consider landing as soon as is practical. They must also consume 10-15g of readily absorbed carbohydrate and re-test their blood sugar level after 15 minutes.

Participants in the study had either type 1 (84 per cent) or type 2 (16 per cent) diabetes and had been issued with Class 1 (61 per cent), or Class 2 (39 per cent) medical certificates. Most were male (96 per cent), with a median age of 44 years, a median diabetes duration of 10.9 years, and a median follow-up period of 4.3 years after the receipt of their medical certificate.

Pilots had a mean HbA1c level of 55.0

mmol/mol (7.2 per cent), and a postcertification mean of 55.1 (7.2 per cent). A total of 38,621 blood glucose measurements were taken during 22,078 flying hours, of which 97.69 per cent were within the green range, 1.42 per cent within the low amber range and 0.75 per cent within the high ‘amber range. Only 0.12 per cent of measurements fell within the low ‘red’ range, and just 0.02 per cent were within the high ‘red’ range.

Out of range readings declined from 5.7 per cent in 2013 to 1.2 per cent in 2019, while no episodes of pilot incapacitation occurred and none of the study participants showed a deterioration of their glycaemic control during the 7.5 years of the study.

Use of a ‘tra c light’ system provided a straightforward way of alerting pilots of the need to take preventive action to avoid impairment of performance or decision making that could arise from unduly high or low blood glucose levels.

The authors conclude that the protocol is practical and feasible to implement and has performed well. There were no reports of pilot incapacitation during flights, and no events occurred in which safety was compromised. They point out that this study represents the most extensive data set for people with insulintreated diabetes working in a ‘safetycritical’ occupation. ■

5 Endocrinology and Diabetology | Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020

Insulin pump therapy uptake low in Ireland due to lack of standardised criteria and care

AUTHOR: Priscilla Lynch

New Irish research has identified that insu cient structure of the health service, lack of awareness and individual preferences are among barriers for adults with type 1 diabetes in getting insulin pump therapy. The study, led by researchers from RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, is published in a recent edition of Acta Diabetologica

This research builds on previous studies by RCSI researchers, which showed that people with type 1 diabetes in Ireland use insulin pump therapy at lowered rates compared internationally and there is an unequal availability of insulin pump therapy in Irish adult diabetes clinics.

Even though insulin pump therapy is recommended as a first-choice therapy for pre-schoolers and is beneficial for people with type 1 diabetes of all ages, only 10.5 per cent of people with type 1 diabetes in Ireland are using a pump to administer their insulin. This compares significantly lower to the average uptake in Nordic, central, and western countries, which was 15–20 per cent in 2010.

Regional disparities in insulin pump use in Ireland were found, with uptake as low as 2 per cent among adults in Roscommon compared to 9.6 per cent in Kildare. One-third of Irish adult clinics, usually in rural areas, do not o er any type of insulin pump therapy support, and less than half provide training to commence the therapy.

To identify the reasons for why uptake is lower in Ireland, the researchers conducted 21 interviews and four focus groups among people with type 1 diabetes, healthcare professionals and other key stakeholders.

The same topics were discussed in all groups and aligned with four main themes: awareness, structure, capacity and impact of an individual (a person with diabetes or healthcare

professional). The main finding was that if the structure of the health service is insu cient, the quality of care is not standardised and capacity is poor, the uptake of insulin pump therapy is more reliant on the individual’s interest, leadership skills, willingness and motivation.

“These factors may make the regional di erences in accessing diabetes related technology and the quality of care more evident,” said Dr Katarzyna Gajewska, the study’s lead author and HRB PhD scholar in population health and health service research

NUI GALWAY SEEK PARTICIPANTS FOR DIABETES PREVENTION STUDY

Researchers from the School of Psychology in NUI Galway are inviting people to share their views on diabetes, diet, physical activity, and a programme that uses a smartphone app and live health coaching to help people improve their health. The PRE-T2D (Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes) study is a 15-minute online survey that is open to all people aged over 18 living in Ireland and ndings will be critical to the development of an online diabetes prevention programme to be delivered in Ireland.

Luke Van Rhoon, PhD Candidate in Health Psychology, Health Behaviour Change Research Group, NUI Galway, said: “We aim not only to prevent diabetes, but help people to better manage their diet, exercise, and daily stress in the long run. This is particularly important as we currently face many new physical and psychological challenges due to the emergence of Covid-19.

“Technology is becoming increasingly vital in the self-management of our health and how we communicate with healthcare professionals, friends, and family. Although

at RCSI. “The results of this study may inform healthcare professionals and policy makers regarding gaps in the delivery of diabetes care. Solutions are needed to reduce the disparities in health service provision in the countries where reimbursement of diabetes technology is o ered. Such steps may include the development of national guidelines, models of care, and structured approaches to provide equal access to insulin pump therapy across the country.”

Study link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007 per cent2Fs00592-020-01595-5

online diabetes prevention programmes have been successfully implemented in other countries, it is important to create a unique programme that suits the needs of the Irish population.”

This study is funded by the Irish Research Council and is supervised by Prof Molly Byrne and Dr Jenny McSharry, Directors of the Health Behaviour Change Research Group at NUI Galway. Prof Byrne said online programmes can overcome some of the challenges a ecting face-to-face programmes, “and we now know from the research that digital health interventions can be e ective in increasing physical activity, changing diets and promoting weight loss. Our research, which is being conducted in collaboration with the National Programme for Diabetes, will provide really important ndings to ensure that online diabetes prevention programmes which are developed in Ireland are usable by the people who will bene t most from them.”

For more information about the PRE-T2D study visit, www.pret2d.com/survey or contact Luke Van Rhoon at l.vanrhoon1@ nuigalway.ie

Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology 6

The 1st polypill licensed for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in Ireland

Thanks to you...

Aspirin Atorvastatin Ramipril

6 Available Formulations

Reduce pill burden by 730 pills per year*

Capsules shown are not actual size. Capsules are Size 0. Please refer to SmPC before prescribing.

*The calculation of a reduction of 730 pills per year is based on a patient taking the three individual components of Trinomia (aspirin, atorvastatin, ramipril) on a daily basis for 365 days compared to a patient taking a Trinomia capsule once daily for 365 days.

Trinomia 100 mg/20 mg/10 mg, 100 mg/20 mg/5 mg, 100 mg/20 mg/2.5 mg hard capsules (acetylsalicylic acid, atorvastatin (as atorvastatin calcium trihydrate) and ramipril) and Trinomia 100 mg/40 mg/10 mg, 100 mg/40 mg/5 mg, 100 mg/40 mg/2.5 mg hard capsules (acetylsalicylic acid, atorvastatin (as atorvastatin calcium trihydrate) and ramipril) Abbreviated Prescribing Information Please consult the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for full prescribing information. Presentation: Hard capsules containing: two 50 mg acetylsalicylic film-coated tablets, two 10 mg atorvastatin film-coated tablets and one 10 mg ramipril film-coated tablet; or two 50 mg acetylsalicylic filmcoated tablet, two 10 mg atorvastatin film-coated tablets and one 5 mg ramipril film-coated tablet; or two 50 mg acetylsalicylic film-coated tablet, two 10 mg atorvastatin film-coated tablets and one 2.5 mg ramipril film-coated tablet; or two 50 mg acetylsalicylic film-coated tablets, two 20 mg atorvastatin film-coated tablets and one 10 mg ramipril film-coated tablet; or two 50 mg acetylsalicylic film-coated tablet, two 20 mg atorvastatin film-coated tablets and one 5 mg ramipril film-coated tablet; or two 50 mg acetylsalicylic film-coated tablet, two 20 mg atorvastatin film-coated tablets and one 2.5 mg ramipril film-coated tablet. Uses: Secondary prevention of cardiovascular accidents as substitution therapy in adult patients adequately controlled with the monocomponents given concomitantly at equivalent therapeutic doses Dosage: Oral administration. 1 capsule per day, preferably after a meal. Swallow with liquid. Do not chew or crush. Avoid grapefruit juice. Patients currently controlled with equivalent therapeutic doses of acetylsalicylic acid, atorvastatin and ramipril can be directly switched. Treatment initiation should take place under medical supervision. Cardiovascular prevention, target maintenance dose of Ramipril is 10 mg once daily. Daily dose in renal impairment based on creatinine clearance - ≥ 60 ml/min, maximum daily dose is 10 mg ramipril; 30-60 ml/min, maximum daily dose is 5 mg ramipril. Contraindicated in hemodialysis and/or with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 ml/min). Administer with caution with hepatic impairment. Perform liver function tests before initiation of treatment and periodically thereafter. Maximum daily dose is 2.5 mg ramipril and initiate treatment under close medical supervision. Contraindicated in severe or active hepatic impairment. Start treatment in very old and frail patients with caution. In patients taking elbasvir/grazoprevir concomitantly with atorvastatin, the dose of atorvastatin should not exceed 20 mg/day. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to any component, to other salicylates, to NSAIDs, to any other ACE inhibitors, tartrazine, soya or peanut. History of previous asthma attacks or other allergic reactions to salicylic acid or other NSAIDs. Active, or history of recurrent peptic ulcer and/or gastric/intestinal haemorrhage, other kinds of bleeding. Haemophilia and other bleeding disorders. Severe kidney and liver impairment. Hemodialysis. Severe heart failure. Concomitant treatment with methotrexate at a dosage of 15 mg or more per week. Concomitant use with aliskiren-containing products with diabetes mellitus or renal impairment. Nasal polyps associated with ashma induced or exacerbated by acetylsalicylic acid. Active liver disease or unexplained persistent elevations of serum transaminases. Pregnancy, lactation and in women of child-bearing potential not using appropriate contraceptive measures. Concomitant treatment with tipranavir, ritonavir, ciclosporin, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir,sacubitril/valsartan therapy. Trinomia must not be initiated earlier than 36 hours after the last dose of sacubitril/valsartan. History of angioedema. Extracorporeal treatments leading to contact of blood with negatively charged surfaces. Significant bilateral renal artery stenosis or renal artery stenosis in a single functioning kidney. Hypotensive or haemodynamically unstable states. Children and adolescents below 18 years of age. Warnings and Precautions: Only for use as a substitution therapy in patientsadequately controlled with the monocomponents given concomitantly at equivalent therapeutic doses. Special populations requiring particularly careful medical supervision: Hypersensitivity to other analgesics/antiinflammatory/antipyretic/antirheumatics or other allergens. Other known allergies, bronchial asthma, hay fever, swollen nasal mucous membranes and other chronic respiratory diseases. History of gastric or enteric ulcers, or of gastrointestinal bleeding. Reduced liver and/or renal function. Particular risk of hypotension: strongly activated renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, transient or persistent heart failure post MI, risk of cardiac or cerebral ischemia, in case of acute hypotension medical supervision including blood pressure monitoring is necessary. Deterioration of cardiovascular circulation. Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Risk of elevated levels of uric acid. Consumption of substantial quantities of alcohol and/or have a history of liver disease. Diagnosed pregnancy, stop treatment immediately, and, if appropriate, start alternative therapy. ACE inhibitors cause higher rate of angioedema in black patients than in non-black patients. The blood pressure lowering effect of ACE inhibitors is somewhat less in black patients than non-black patients. Monitoring during treatment is required for: Concomitant treatment with NSAIDs, corticosteroids, SSRIs, antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, ibuprofen. Signs or symptoms suggestive of liver injury. Stop treatment temporarily prior to elective major surgery and when any major medical or surgical condition occurs. Particularly careful monitoring is required in patients with renal impairment, risk of impairment of renal function, particularly with congestive heart failure or after a renal transplant. Serum potassium: ACE inhibitors can cause hyperkalemia in patients with impaired renal function and/or in patients taking potassium supplements (including salt substitutes), potassium-sparing diuretics, trimethoprim or co-trimoxazole and especially aldosterone antagonists or angiotensin-receptor blockers, hyperkalemia can occur. Potassium-sparing diuretics and angiotensin-receptor blockers should be used with caution in patients receiving ACE inhibitors, and serum potassium and renal function should be monitored. Other situations that may increase the risk of hyperkalaemia are: age >70 years, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, dehydration, acute cardiac decompensation or metabolic acidosis.Specific side-effects: Perform liver function tests before use and monitor periodically and with liver injury or increased transaminase levels. Use with caution with substantial alcohol use or history of liver disease. Potential risk of hemorrhagic stroke. May affect the skeletal muscle and cause myalgia, myositis, and myopathy that may progress to rhabdomyolysis, ask patients to promptly report skeletal muscle effects (muscle pains, cramps or weakness) especially if accompanied by malasie or fever and measure CK levels, stop treatment if significantly elevated or if severe muscular symptoms occur. Prescribe with caution in patients with pre-disposing factors for rhabdomyolysis. Benefit/risk of treatment should be considered and clinical monitoring recommended. Do not measure CK following strenuous exercise or in presence of plausible alternative cause of CK increase. If CK levels significantly elevated at baseline, re-measure levels 5 to 7 days later to confirm the results. Risk of rhabdomyolsis with use of potent CYP3A4 inhibitors, transport proteins or HIV protease inhibitors. Consider alternative treatments if risk of myopathy. Consider lower starting or maximum dose and appropriate clinical monitoring with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors and medicinal products that increase the plasma concentration of atorvastatin respectively. The risk of myopathy may also be increased with the concomitant use of gemfibrozil and other fibric acid derivates, antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C (HCV) (boceprevir, telaprevir, elvasvir/grazoprevir), erythromycin, niacin or ezetimibe. Do not co-administer with systemic fusidic acid or within 7 days of stopping fusidic acid. Where use of systemic fusidic acid considered essential, discontinue statin treatment during fusidic acid treatment. Reports of rhabdomyolysis in patients receiving fusidic acid and statins in combination. Where prolonged systemic fusidic acid needed, consider need for co-administration of Trinomia and fusidic acid on case by case basis with close medical supervision. Discontinue statin treatment if interstitial lung disease occurs. Monitor patients at risk of diabetes mellitus. Discontinue treatment if angioedema occurs and initiate emergency treatment promptly. Concomitant use of ACE inhibitors with sacubitril/valsartan is contraindicated. due to the increased risk of angioedema. Treatment with sacubitril/valsartan must not be initiated earlier than 36 hours after the last dose of Trimomia. Caution should be used when starting racecadotril, mTOR inhibitors and vildagliptin in a patient already taking an ACE inhibitor as there is an increased risk of angioedema. Concomitant use of ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers or aliskiren is not recommended and should not be used in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Anaphylactic reactions during desensitization, consider temporary discontinuation of Trinomia during desensitization. Monitor white blood cells for neutropenia/agranulocytosis and more regularly in the initial phase of treatment, impaired renal function, concomitant collagen disease and other medicines that can change the blood picture. Cough. Contains lactose. Patients with rare hereditary problems of galactose intolerance, the Lapp lactase deficiency or glucose-galactose malabsorption should not take this medicine. Interactions: Acetylsalicylic acid: other platelet aggregation inhibitors, other NSAIDs, and antirheumatics, systemic glucocorticoids, diuretics, alcohol, SSRIs, uricosuric agents, metamizole, anticoagulant and thrombolytic therapy, digoxin, antidiabetic agents including insulin, methotrexate, valproic acid, antacids, ACE inhibitors, ciclosporin, vancomycin, interferon , lithium, barbiturates, zidovudine, phenytoin, laboratory tests. Atorvastatin: CYP3A4 inhibitors, CYP3A4 inducers, transport protein inhibitors, gemfibrozil/fibric acid derivatives, ezetimibe, colestipol, fusidic acid, colchicine, digoxin, oral contraceptives, warfarin. Ramipril: potassium salts, heparin, potassium-retaining diuretics and other plasma potassium increasing active substances, antihypertensive agents and other substances that may decrease blood pressure, vasopressor sympathomimetics and other substances, allopurinol, immunosuppressants, corticosteroids, procainamide, cytostatics and other substances that may change the blood cell count, lithium salts, antidiabetic agents including insulin. Monitor as appropriate. Consider lower maximum dose of atorvastatin with potent CYP3A4 inhibitors. Pregnancy and Lactation: Contraindicated in pregnancy and breast-feeding. Women of child-bearing potential should use effective contraception during treatment. Side Effects: Ramipril: Common (≥1/100, <1/10): dyspepsia, nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, digestive disturbances, abdominal discomfort, gastrointestinal inflammation, non-productive tickling cough, bronchitis, sinusitis, dyspnoea, headache, dizziness, rash in particular maculo-papular, blood potassium increased, myalgia, muscle spasms, chest pain, fatigue, hypotension, orthostatic blood pressure decreased, syncope. Atorvastatin: Common: dyspepsia, nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, flatulence, pharyngolaryngeal pain, epistaxis, nasopharyngitis, headache, allergic reactions, hyperglycaemia, myalgia, muscle spasms, pain in extremity, joint swelling, back pain, arthralgia, liver function test abnormal, blood creatine kinase increased. ASA: Very Common (≥ 1/10): Gastrointestinal complaints such as heartburn, nausea, vomiting, stomach ache and diarrhea, minor blood loss from the gastrointestinal tract (micro-bleeding). Common: Paroxysmal bronchospasm, serious dyspnoea, rhinitis, nasal congestion. For less frequent side effects see SmPC. Pack Sizes: Blister containing 28 hard capsules. Legal Category: POM. Product Authorisation Numbers: PA 1744/002/001-006 Product Authorisation

aspirin • atorvastatin

AspirinAtorvastatinRamipril 100mg 20mg 2.5mg 100mg 20mg 5mg 100mg 20mg 10mg 100mg 40mg 2.5mg 100mg 40mg 5mg 100mg 40mg 10mg

Holder: Ferrer Internacional, S.A., Gran Vía Carlos III, 94, 08028 Barcelona, Spain. Marketed by: A. Menarini Pharmaceuticals Ireland Ltd. Further information is available on request from A. Menarini Pharmaceuticals Ireland Ltd, 2nd Floor, Castlecourt, Monkstown Farm, Monkstown, Glenageary, Co. Dublin A96 T924 or may be found in the SmPC. Date of Preparation: March 2020 Date of item: July 2020. IR-TRI-05-2020 References: 1. Trinomia 100mg / 40mg / 10mg, 100mg / 40mg / 5mg, 100mg / 40mg / 2.5mg SmPC March 2020 2. Trinomia 100mg / 20mg / 10mg, 100mg / 20mg / 5mg, 100mg / 20mg / 2.5mg SmPC March 2020

Getting diabetes services back up and running during Covid-19

AUTHOR: Paul Mulholland

The Covid-19 pandemic has had significant ramifications for patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes. Like other parts of the health services, traditional diabetes clinics were paused in the early months of the crisis. During this time, consultations began taking place virtually, with healthcare practitioners providing advice around self-management of the condition.

However, as normal services resumed, some patients with diabetes were still reluctant to attend their hospital appointments as they are in an ‘at-risk’ group in terms of Covid-19 infection. This led the HSE and Diabetes Ireland to issue a call, urging people with concerns about their diabetes to seek medical advice from their pharmacist, GP, or hospital diabetes team.

Speaking to Update, Prof Sean Dinneen, Consultant Endocrinologist at Galway University Hospital (GUH) and Clinical Lead of the HSE National Clinical Programme for Diabetes, said it was important that patients with diabetes were aware of the availability of support and care, despite the pandemic.

“We’ve noticed that patients are not always keen to come to hospital,” stated Prof Dinneen.

“There is a fear of contracting the virus, perhaps reduced in recent weeks, but I suspect starting to ramp up again now. And it is trying, I suppose, to walk that tightrope between providing care and getting services back up and running, and at the same time trying to get people to focus on health management of their diabetes.”

One positive factor of the early lockdown, Prof Dinneen said, is that many people have become more proactive in terms of managing their condition.

However, he added that his “strong impression” from talking to colleagues around the country is that patients are presenting at a later stage with complications arising from their diabetes.

“Patients are not coming at the appropriate time,” he told Update.

“And what we are seeing is later presentations of problems that could have been more easily dealt with, if they

presented earlier. Diabetic foot is a good example. If you don’t come early, the problem can get worse and be more di cult to manage. I think that ophthalmologists are also concerned about patients with visual symptoms presenting later.”

National registry

In the absence of a national register for diabetes, Prof Dinneen said it was di cult to specifically say what impact the pandemic has had on people with the condition.

Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology 8

There is a fear of contracting the virus, perhaps reduced in recent weeks, but I suspect starting to ramp up again now. And it is trying, I suppose, to walk that tightrope between providing care and getting services back up and running...

Prof Sean Dinneen

“One of my bugbears is a lot of our colleagues across Europe have a better handle of their diabetes population than us,” he commented.

“Without a national diabetes registry, we are really missing out on the opportunity to track how people are doing. If you said to me, what impact did Covid-19 have on people with diabetes in Ireland, the honest answer is I don’t know.”

A Sláintecare-funded project to establish such a registry has been paused as the team behind its development, which mainly consisted of public health doctors and specialists, were redeployed as a result of the pandemic.

“We need to know who has it and what sort of burden of complications and what sort of burden of illness are we dealing with. And we have the wherewithal now, because we have Diabetic RetinaScreen up and running. RetinaScreen is aware of somewhere in the region of 180,000 people with diabetes in Ireland. So we can build on that. And there is also the new chronic disease management GP contract. The plan we have for the Sláintecare project is to merge those two sources of data, and try to establish a proper national diabetes registry over the next few years. I think Covid has highlighted that need even more.”

The redeployment of healthcare sta from various parts of the health service to assist in the fight against the pandemic has impacted on diabetes teams, according to Prof Dinneen. He said HSE management has been informed about the need for sta to return to diabetes services.

“And I think that message has gotten across,” he said.

“However, we still don’t have a full complement of our community podiatrists here in CHO 2” [Community Healthcare Organisation, Area 2, which covers Galway, Roscommon, and Mayo].

Prof Dinneen said that his department in GUH reached out to all patients who were booked to have a face-to-face appointment.

“Not every department around the country was able to do that, but we did, mainly by phone,” he said.

“We are only beginning to embrace the world of video conferencing with our patients. I know other departments have already got up and running with that function. We have used it mainly for our own internal meetings. And teaching and things like that are resuming now, with Zoom and Microsoft Teams. But in our own case here in Galway it is mainly phone contact with patients that we’ve used. Attend Anywhere and other HSE-supported software are coming into the frame now and people are beginning to use that telemedicine or video conferencing with patients.”

Telemedicine consultations are more suitable for patients who have previously attended the clinic, according to Prof Dinneen. He added that younger patients,

in particular, value this type of consultation.

“We would have a very high non-attendance rate in our young adult clinics in general. For whatever reasons they don’t turn up,” he said.

“We had almost zero non-attendance because we could connect in with them remotely. And they love it.”

However, he said for patients attending for the first time, or for complicated cases, face-to-face interactions were vital, even if telemedicine had the potential to “change practice”.

“If it is a straightforward visit, we should and we will in the future, do it remotely,” he said.

“The challenge is identifying the straightforward visit. Because sometimes a visit you think will be straightforward turns out to be anything but.” ■

HSE LAUNCHES LIVING WELL FREE ONLINE PROGRAMME SUPPORTING PEOPLE WITH LONG-TERM HEALTH CONDITIONS DURING COVID-19

The HSE National Self-Management Support team recently o cially launched the Living Well Programme, a series of online workshops designed to o er support to people living with long-term health conditions, including diabetes.

Living Well is a free group programme which runs online for six weeks. There is one workshop a week, which lasts 2.5 hours. Workshops are delivered in a relaxed and friendly way so that all participants can learn from each other. There are a maximum of 12 people in a programme. Two trained facilitators run the workshops each week. At least one of the facilitators lives with a long-term health condition.

The Living Well Programme has received Sláintecare integrated funding to enable delivery during 2020/2021. The programme was previously delivered in a face-to-face community setting, but it has been made available online during the

Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr Derval Howley, Chair of Interim HSE National Advisory Group for Self Management Support, said: “People taking part in the workshops may have di erent health conditions, however, they all face similar challenges - for example managing medications, attending healthcare appointments, communicating with healthcare professionals, coping with pain, fatigue, and di cult emotions. Living Well is a fantastic free programme which builds con dence and helps participants develop the skills required to better manage their conditions in a supportive and safe way.”

Anyone with a long-term health condition interested in taking part in this programme can register by contacting their local Living Well Team, contact details of which are available at www.hse.ie/livingwell, or contact HSELive on 1850 24 1850 / 01 240 8720 or email hselive@hse.ie.

9 Endocrinology and Diabetology | Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020

Is obesity really a disease?

AUTHORS: Dr Finian Fallon and Prof Carel le Roux, Obesity Complications Clinic, St Vincent’s Healthcare Group, Dublin

Since the World Health Organisation (WHO) recognised obesity as a chronic disease in 2000, there has been a slowly building consensus in healthcare that obesity can or should be treatable within the medical paradigm. Despite growing recognition that obesity is a complex phenomenon, the idea that obesity is a kind of moral choice remains somewhat ingrained in our culture, including among many of those who are living with obesity and among many healthcare professionals who care for patients with obesity.

While changes around food intake and lifestyle choices related to obesity remain relevant interventions, from a scientific perspective increasingly the evidence is demonstrating that obesity is a biologically embedded process. As such, we are seeing that the solution for the epidemic of obesity, if there is one, is increasingly outside the realm of willpower and moral fibre. Instead, research is proving that appropriate treatment trajectories reside in our medically grounded understanding that, similar to cancer not being one uniform disease, obesity appears to have many subsets of disease all contributing to excess adipose tissue. While treatment vectors may include food and lifestyle choices, these elements of our interventions are not e ective for all forms of obesity. This is often contrary to the lay public, and often health professionals’ beliefs. The ‘eat less, move more’ message has sustained a huge and growing worldwide diet industry for many decades and is an implicit position in many encounters between patients and medical interventionists. However, the science has shown that for most forms of obesity this message simply is not enough.

Blame culture

In a recent study carried out by Grannell et al (2020) we see how the blame culture that surrounds obesity can lead to

stigma and a reduction in health-seeking behaviours among those with obesity. In this study of 52 patients with obesity, contradictory perspectives emerge about patient beliefs and perceptions around obesity as a disease, its treatment and its causes. Patients in the study tended to agree with an apparently contradictory belief: while agreeing that obesity is a disease, they tend to agree that its solution is related to willpower. In essence, as the study finds, “there is a discrepancy between recognition that obesity is a chronic disease and treating obesity as a chronic disease.” This “misalignment” may perpetuate stigma, and impacts healthseeking behaviours and engagement with services when help is sought. Patients also had conflicting views on the relevance and importance of exercise to weight loss. Again, the prevailing view that exercise can have a significant impact on weight loss may be true for a few forms of obesity but increasingly its benefit is seen in the aftermath of weight loss during the weight loss maintenance period.

The message that Grannell et al are o ering in this research is that there is a pressing need to move from a focus on weight loss alone, to one which is primarily concerned with health gain. They argue that this message is part of a necessary reframing of obesity requiring treatment like any other chronic disease. This would still include exercise and food intake as an element, but does not have as its main focus the stigmatising and generally ine ective ‘eat less, move more’ refrain that echoes around the world of weight loss. This health gain focus is essentially, they argue, one which is grounded in an understanding of obesity as a disease which recognises the biological determinants of obesity, albeit embedded in a complex array of forces which are internal and external to the individual.

Covid-19

Covid-19 has added another layer of complexity to our response and understanding of the disease of obesity. Grannell et al (2020) also carried out a qualitative study into the fears of those with obesity during the pandemic. Their findings indicate that those with obesity are at risk of additional weight gain and increased existential anxiety in the context of under-resourced obesity services. Patients are reporting challenges in accessing services, maintaining routine and exercising. These are challenges that speak to the need for careful consideration of the mental health complications associated with obesity and the experience of stigma. There is a risk of a two-tiered society developing, between the haves and have nots of those living with obesity and those with less visible conditions, with one group facilitated to return to normal living in spite of the risks of developing Covid-19, while another group of those with obesity are at risk of experiencing the fear and stigma that confronts those with this often visually apparent disease. Professionals are under an onus to ensure that public debate is sensitive to the risk of ‘othering’ those with obesity, in addition to the need for increasing awareness of the benefits of additional resourcing for obesity services. This is not to privilege obesity, but seeks to recognise the public health and societal benefits of appropriate and thorough recognition of obesity as a disease that can be treated.

Future advances

The science of endocrinology and obesity has progressed rapidly in recent years. While di erent fields have made great claims in relation to the possibilities of scientific knowledge, which ultimately prove overly confident, the next 10 years in the field of medicine may well o er a novel gateway into the world of personalised treatments for obesity. It may be that the utilisation of artificial intelligence to help

Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology 10

manage the complex balancing of hormonal and other biological and neurological processes will lead to more widely successful, truly individualised obesity treatments. These interventions may well incorporate more focused surgical procedures or medical devices with enhanced medications.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the science which focuses

on obesity as a disease and one which is focused on health gain is more e ective than the one which dominates the prevailing discourse around obesity. The prevailing discourse is one which perpetuates unconscious biases, often contained in well-intentioned messages, among both patients and health professionals. By declaring obesity a disease, we are giving agency to patients, but also to

healthcare professionals. Our healthcare systems are getting better all the time in managing chronic diseases. Our task is to ensure that obesity is accepted and treated as one of those diseases and apply the same processes and level of acceptance that we would for any other complex and chronic disease. ■

References on request

Maintaining obesity services amid Covid-19

AUTHOR: Priscilla Lynch

The Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (IrSPEN) has cautioned that patients with obesity are at higher risk of complications from Covid-19 – and need equal access to treatments as the health system begins to address backlogs and schedule new appointments.

To help manage this challenge, obesity consultants from around the world have together published guidance on prioritising access to surgery and treatments for those with obesity and associated diabetes.

Tallaght University Hospital Consultant Endocrinologist, Dr Conor Woods stated: “Similar to most elective surgery, metabolic procedures have been postponed during the pandemic. However, due to the progressive nature of diabetes, delaying surgery can increase future health complications and even earlier death.

“The traditional ‘weight-centric’ criteria for patient prioritisation needs to change. For the period ahead, a new triaging approach for obesity and diabetes surgeries and treatments has been agreed internationally.”

Guidelines

If patients are well enough to be safe surgical candidates, preference should be a orded to those with the greatest risk of morbidity and mortality from their disease, if it is probable that this risk can be reduced by surgery, the new guidelines note. This logic would apply, for instance, to many surgical candidates

with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes or substantial metabolic, respiratory, or cardiovascular disease.

Traditional BMI-centric criteria for patient selection, however, tend to skew access to bariatric and metabolic surgery in the opposite direction. Despite strong evidence that surgery achieves its greatest health benefits among patients with type 2 diabetes, a minority of those who have such operations have preoperative type 2 diabetes or cardiometabolic disease, the guidelines state.

Furthermore, the document notes that in many publicly funded healthcare systems, candidates for bariatric and metabolic surgery are currently placed on a single elective surgery waiting list, regardless of their indication. Priority is established largely on a first-come first-served basis, rather than on clinical need. “This approach is comparable to putting all colorectal surgery candidates on the same waiting list with similar priority, regardless of whether their diagnosis is cancer or benign neoplasia. A strong need therefore exists for clinically sound criteria to help prioritise access to surgery in times of pandemics with limited resources. These criteria can also inform future waiting list management and decision making about the structure of surgical services,” the guidelines say.

The guidelines recommend that patients be prioritised into three categories:

▸ Surgery within 30 days for those who have complications of previous metabolic surgery.

▸ Surgery within 90 days for patients with substantial risk of complications of diabetes or who have poor control of their diabetes, despite complex medical regimens or using insulin.

▸ Standard access to surgery for patients who are unlikely to deteriorate within six months, but these patients need to be optimised using intensive medical treatment.

Given the risks of severe complications from Covid-19 in patients with diabetes and obesity, the recommendations include that Covid-19 screening be mandatory prior to any obesity treatment, that keyhole surgery remains the best approach and that personal protective equipment (PPE) should be used.

IrSPEN member and Metabolic Surgeon Prof Helen Heneghan added: “Although we will be particularly focussed on how we should restart activity in the immediate post-Covid-19 period, the new guidelines also provide a framework for clinical prioritisation long into the future.”

James Cushnan, a patient from Letterkenny with diabetes who had his metabolic surgery postponed due to Covid-19, added: “Doctors, policymakers, and hospital managers must recognise the seriousness of diseases that require metabolic surgery and ensure these operations are not further delayed due to the widespread misconception that obesity and diabetes are lifestyle conditions of laziness and that surgery is a ‘last resort’.” ■

11 Endocrinology and Diabetology | Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020

Advances in diabetes technology

AUTHOR: Dr Anna Clarke, Advocacy and Research Manager, Diabetes Ireland

Diabetes is a serious health issue with approximately 225,000 people diagnosed in Ireland, which poses a challenging problem for acute and community services. Acute services are required to provide care for all people with type 1 diabetes and all complicated type 2 cases, leaving the remaining 100,000 people to get routine care at community level. Diabetes care has advanced with more options for medical management, increased emphasis on self-management, improved technology solutions for glucose monitoring and delivery of insulin, but the focus of care remains on optimisation of glucose, cholesterol and blood pressure to reduce diabetes complications. For most people this requires daily decision making regarding food intake, medication and activity balance and for many a continuous struggle between hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia.

Diabetes technologies have improved health outcomes; eg, pump technology compared to multiple daily injections improves glycaemic control and gives greater flexibility in daily life.

Technology advances o er motivated individuals more precise dosage regimes and glucose fluctuation information thereby giving enhanced safety and discretion. However, technology may increase diabetes burden with di erent age groups perceiving di erent advantages and disadvantages to its usage.

This article focuses on devices used for insulin administration, glucose measurement and assisted insulin adjustment currently available in Ireland, acknowledging that access to newer technologies is limited by cost and personal factors. This article is relevant to 2020 only as technology advances happen rapidly with new iterations happening annually.

Insulin administration

Traditionally, syringes/vials were used to administer insulin but now insulin pens are the most widely used devices for delivering insulin. Continuous insulin administration, ie, insulin pumps are computer assisted methods of insulin administration introduced in the 1970s. Gajewska et al (2020) reported that 2,111 people in Ireland are using insulin pumps with a five-fold increased prevalence among children and adolescents. Insulin pumps are similar in size to a mobile phone and programmed to release doses of insulin continuously (basal), or as a surge (bolus) to control blood glucose levels post carbohydrate consumption. The basal rates are pre-programmed or automatically calculated by the pump. Bolus doses are calculated by the individual (technology can assist) in response to carbohydrate consumed or to correct a high glucose reading. As a general rule, approximately 50 per cent of the total daily insulin dose is used as basal insulin and 50 per cent as bolus insulin. A reservoir is filled with rapid-acting insulin and connected to an infusion set inserted into the subcutaneous tissue and renewed every two-to-three days. Hence, these devices are attached to the person continuously.

Sensor augmented pumps such as the Medtronic Veo, used with appropriate glucose sensor technology, allow the setting of alarms at low glucose levels to trigger insulin cut-o . Newer pumps allow for predictive low glucose suspend, ie, Medtronic 640G uses an algorithm to predict that a low glucose level will occur within 30 minutes and suspends insulin delivery. The Medtronic 670G uses hybrid closed-loop technology, which involves complex predictive algorithms to automatically increase, decrease or suspend insulin delivery to keep glucose levels at a specific target glucose of 6.7mmol/L,

e ectively minimising hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia. However, unless in complete automatic mode, carb counting and appropriate bolus insulin are required. It is expected that the Medtronic 780G will be available soon in Ireland.

PEOPLE USING PUMPS EMPLOY TERMINOLOGY

SUCH AS:

▸ Insulin to carbohydrate ratio (ICR): the amount of carbohydrate consumed that requires one unit of insulin to maintain glucose levels.

▸ Insulin sensitivity factor (ISF): the e ect one unit of insulin has in lowering glucose levels.

▸ Insulin on board/active insulin: the amount of insulin still active in the body from a previous bolus. It is essential to know this when calculating the next bolus to reduce the risk of insulin stacking and hypoglycaemia.

There are risks associated with pumps including pump failure, line occlusions, infusion site reactions/infection or fat accumulation, ie, lipohypertrophy. These episodes are not infrequent and education regarding troubleshooting and vigilance is required to avoid acute hyperglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Glucose monitoring

The most common method of glucose monitoring for people with diabetes requiring home glucose checks remains the home blood glucose meter (HBGM) or spot glucose testing. A finger prick is undertaken and blood applied to a test strip inserted into a meter, which gives a visual or audible reading in five-to-15 seconds. Measurement of glucose levels allows the person to recognise out-ofrange results and take action, such as selecting an appropriate dose of insulin

Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology 12

or carbohydrate intake or implement dietary or other lifestyle changes. Each person in conjunction with their diabetes team devises a frequency of testing and targets to be achieved with a detailed plan of action for out-of-range levels. Many types of portable blood glucose meters are available, from basic models to moreadvanced meters with multiple features and options. More recent developments are the advent of the finger prick being replaced by sensors.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) requires a small electrode (sensor) to be inserted under the skin which measures interstitial fluid glucose levels every five minutes and displayed on a device/reader or a smartphone/watch. An alarm can be set to alert of glucose levels that are too low or too high or the data can be linked to an insulin pump.

Flash glucose monitors (FGM) requires a sensor applied on the skin, which measures interstitial glucose levels every five minutes and is stored in the sensor to be read by a reader or smartphone app. The display shows a trend arrow indicating if glucose levels are rising or falling but does not allow for alarm settings or linking to pump therapy yet. Trends highlight the direction that glucose readings are moving and the speed at which they are changing. Trends alert the individual if glucose levels have been rising, falling, or appear to have been stable over several minutes/ hours as opposed to finger stick readings or

individual sensor readings which are only snapshots of glucose levels at that moment. The data available through CGM and FGM can permit significantly more fine-tuned adjustments in insulin dosing and other therapies than HBGM can provide. With nearly 300 measurements a day, CGM/FGM systems o er a new way to evaluate diabetes management by exploring the percentage of the time the person’s glucose readings are within target range: Time in range. For most people, their aim should be to have glucose levels within target range for >70 per cent of the time with less stringent targets for older or high-risk individuals and for those under 25 years of age.

It is important to remember that CGM and FGM measure interstitial glucose levels and that there is a five-to-10 minute delay in interstitial glucose response to changes in blood glucose. Thus, data from a glucose meter is not interchangeable with CGM/ FGM data. Similarly, the trend arrows in CGM/FGM are not interchangeable; refer to individual device manual for interpretation.

Assisted insulin adjustment

The majority of people using insulin to manage their diabetes (almost all people with type 1 diabetes) will calculate their insulin requirement based on their current glucose level and how much carbohydrate they are having in a meal. This is a complex calculation requiring:

▸ knowledge of the carbohydrate content of food to be consumed;

▸ calculate insulin requirement according to individual ICR (may di er based on time of day or month for females);

▸ include extra insulin according to ISF if glucose level above target;

▸ adjust for any active insulin in body;

▸ adjust for planned exercise.

When calculated this is the required insulin dosage. Newer smart meters will allow input of the required data (ICR and ISF can be pre-programmed) and will calculate and record how much insulin is recommended thus minimising mathematical errors.

Conclusion

Advances in technology are changing everyone’s life and while technology can admittedly be helpful it may also burden us with increased engagement; additional information and a constant strive to do better. For people with diabetes the same applies: Advances have reduced the burden of diabetes physical management but at a cost to emotional burden and daily quality-of-life. Technology works for some people but uptake of these systems has been limited by Government policy, financial cost, and individual factors both of the patient and the professional. While there is great interest in new technology, it is important to continue to make best use of available resources to improve outcomes for people with diabetes which currently remain suboptimal mainly due to inadequate manpower investment. ■

13 Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology

Glucose measurement Capillary Interstitial Interstitial Con rmation of accuracy Quality control check Calibration twice daily Not required Finger prick required Yes Yes to calibrate If display indicates hypoglycaemia Duration of strip/sensor Single use Six-to-seven days 14 days Data updating Manual update Every ve minutes to device or pumpRequires scanning using reader Alarm setting No Yes No Visibility Finger prick Disposable sensor is worn on the abdomen Disposable sensor worn on the back of the arm

HOME BLOOD GLUCOSE METERS (HBGM)CONTINUOUS GLUCOSE MONITORING (CGM)FLASH GLUCOSE MONITORING (FGM)

TABLE

1:

Methods for self-monitoring of blood glucose

Closed loop insulin delivery in type 1 diabetes mellitus

AUTHORS: Dr Christine Newman,1 Research Registrar; and Prof Fidelma Dunne,1,2, Consultant Endocrinologist

1 Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes Mellitus, Galway University Hospital

2 College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, National University of Ireland Galway

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a complex, multi-system disorder with chronic health implications. To reduce potential microvascular complications, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends a target haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 53mmol/mol (7 per cent). Despite advances in diabetes technology this target is achieved by only 18 per cent of adults and 21 per cent of children (<18 years old) with T1DM.

In addition to suboptimal control, 7 per cent of all patients with T1DM will experience at least one episode of severe hypoglycaemia per year. Such admissions have significant emotional and economic impact. It is also well described that a fear of hypoglycaemia can lead to a reluctance to achieve good glycaemic control.

Advances in insulin delivery and real time glucose level monitoring have improved diabetes control in recent years. The use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) can reduce both HbA1c and the frequency of hypoglycaemia when compared to multiple daily injections (MDI). Furthermore, real time continuous glucose monitoring (rt-CGM) can lead to improved glycaemic control and reduced rates of severe hypoglycaemia in those with T1DM on MDI. When combined with CSII, CGM can further improve HbA1c and time spent in hypoglycaemia.

Sensor augmented pump therapy, a further advance where insulin administration is automatically suspended at low glucose levels without the need for user intervention, can reduce severe hypoglycaemia in both paediatric and adult populations, however without

statistically significant impacts on HbA1c.

This compelling data combined with quality of life improvements seen with technology use have led to the ADA recommending CSII be considered for “all children and adolescents, especially children under seven years diagnosed with T1DM. Internationally, 44.4 per cent of children with T1DM use CSII therapy.

Though insulin pump therapy has been around in its earliest form since the 1970s, and sensor-augmented pump therapy was undoubtedly a great advance for patients with diabetes, diabetes technology took a further step forward in 2016 when the US FDA approved the first closed loop insulin delivery system for adults. Closed loop insulin delivery continuously feeds real time glucose readings back to the individual’s pump, and automatically makes adjustments without the need for the wearer to change their settings; in this way it is superior to sensor augmented pump therapy.

This article will explore the recent evidence behind closed loop technology and its potential advantages.

Closed loop published data

The ‘Six-month randomised, multicentre trial of closed loop control in type 1 diabetes’ and the ‘Randomised trial of closed-loop control in children with type 1 diabetes’ studies evaluated the e ectiveness of a closed loop insulin delivery system in reducing hypoglycaemia and improving time in range in patients aged 14 years and above and six-13 years respectively. Both of these studies were the longest of their kind published to date.

Both trials were funded by Tandem Diabetes Care and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases.

Study design – adult study

This was an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled study for patients with T1DM aged 14 years or older. Participants were recruited from seven centres in the US. A total of 168 patients were randomised in a 2:1 ratio to receive either a closed loop insulin delivery system (t:slim X2 insulin pump and Dexcom G6 sensor connected by ControlIQ Technology – an algorithm developed in the University of Virginia, US) or a sensor augmented pump (Dexcom G6 with the patient’s personal pump). As the t:slim had not yet received FDA approval an investigational device exemption was granted by the FDA.

All patients had T1DM and had been on insulin therapy, either CSII or MDI, for at least a year prior to randomisation. After enrolment all patients received a two-week run in to optimise glycaemic control. The run-in period was extended up to eight weeks for those unfamiliar with the technology. The patients had site visits at two, six, 13 and 26 weeks and had phone consultations in between these visits. They were required to upload data from their device before each visit and regularly during the trial. HbA1c was also checked twice during the study- at baseline and at 13 and 26 weeks.

This study was briefly interrupted for 33 patients due to a software error in the Control IQ algorithm. Data was included during this period as the patients continued to use the devices in ‘open loop’

Volume 6 | Issue 8 | 2020 | Endocrinology and Diabetology 14

mode ie glucose levels were received by the user and not delivered directly to the pump. The patients then made manual adjustments to their pump settings.

The primary outcome was the percentage of time patients spent with a glucose level of 3.9-10mmol/L. The secondary outcomes included time spent >10mmol/L and 13.9mmol/L, and below 3.9mmol/L and 3mmol/L, average glucose levels, HbA1c at 26 weeks, admissions for DKA and severe hypoglycaemia.

Results

In total 168 patients were randomised between July and October 2018, with 112 patients included in the closed loop group and 56 in the control/SAP group. The average age of participants was 33 years (range 14-71). Most patients had a BMI of >25kg/m; and patients were well matched in both groups for baseline HbA1c (7.6 per cent), educational and financial income status, previous CGM and CSII use. There was excellent retention with a 0 per cent drop-out rate and 100 per cent and 99.9 per cent of inperson and virtual visits completed.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome of this trial was time in range (3.9-10 mmol/L) and this was achieved in 71 + 12 per cent (increased from 61 + 17 per cent) in the closed loop group and remained unchanged at 59 + 14 per cent in the control group. The change in time in range was statistically significant at 11 percentage points (95 per cent CI 9-14, p<0.001). These changes were seen within one month of therapy and continued for the duration of the trial.

The greatest discrepancy in glucose levels between closed loop and SAP was in the early morning between 5-6am.

Secondary outcomes