Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) can turn people into shadows of their former selves

References:

1. Al-Harbi K et al. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012; 6: 369-388.

2. Keller MB. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(Suppl 8): 5-12.

3. Rush AJ et al. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163(11): 1905-1917.

Date of preparation: September 2021

Item code: CP-246536

Up to 30% of patients with MDD fail to respond to their first antidepressant therapy.1,2

More than 2 in 3 responders fail to reach remission – with remission rates declining with each treatment step:3

• 31% achieve remission with a second treatment

• 13% achieve remission with a fourth

It’s time to step out of the shadow of MDD.

Janssen Sciences Ireland,

Ringaskiddy, IRL - Co. Cork P43 FA46

Barnahely,

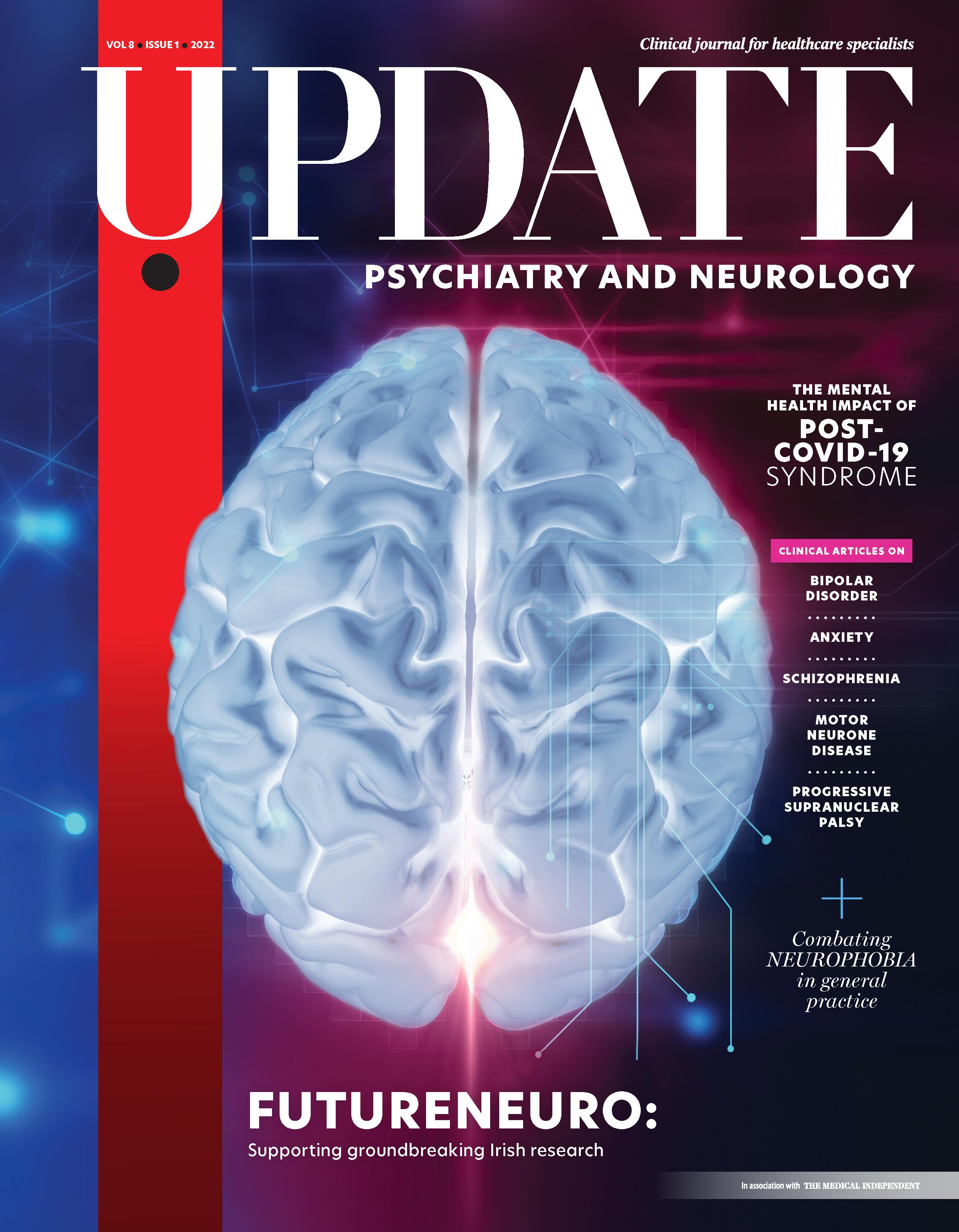

Hoping for better mental health and neurology care this year

A message from Priscilla Lynch, Editor

Welcome to the latest edition of Update Psychiatry and Neurology.

As we begin this new year, the Covid-19 pandemic is continuing to have a substantial impact on our lives.

While there is hope on the near horizon given the emergence of an apparently less virulent variant (omicron), coupled with the success of vaccination and ongoing development of new treatments, the impact on the nation’s mental health and healthcare service provision will be felt for quite some time to come.

As Prof Brendan Kelly outlines in this issue, evidence to date indicates that the combined effects of the pandemic itself and the public health restrictions it necessitates have resulted in approximately one person in every five in the general population experiencing significantly increased psychological distress.

Furthermore, while there continue to be encouraging developments in neurology and psychiatry knowledge, both at home and abroad, basic service provision during the pandemic remains one of the biggest challenges facing those working in the field.

Mental health and neurology professionals in already long under-resourced and understaffed structures in Ireland are doing their best to provide ongoing services to patients. Waiting lists for community-based psychology services and CAMHS and neurological rehabilitation services remain appalling, with the impact of the medical recruitment and retention crisis very apparent.

But, as ever, the need for learning and sharing of information continues.

This issue features a wide range of clinical and research update articles to help increase your knowledge base of brain disorders.

On the medical conference front, there is exclusive coverage from the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland’s latest Winter Meeting.

Focusing on Irish research, there is an article on the latest successes of FutureNeuro, the SFI Research Centre dedicated to developing new technologies and solutions for the treatment, diagnosis, and monitoring of neurological diseases, which highlights the Centre’s important ongoing work.

And, in a very welcome development, this issue features an article explaining how, from this month, the neurology service at Tallaght University Hospital will become an expert centre for both atypical Parkinsonism and cerebellar ataxias and hereditary spastic paraplegias within the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN-RND).

This issue also contains a number of expert management articles on bipolar disorder, anxiety, schizophrenia, medication overuse in migraine, and progressive supranuclear palsy, which outline the most effective treatment approaches, as well as overview articles on motor neurone disease, narcissistic personality disorder, and the evidence to date on the benefits of mindfulness.

There are also timely pieces on the mental health impact of post-Covid-19 syndrome, and tackling neurophobia in Ireland, particularly in general practice.

The College of Psychiatrists of Ireland has just launched a position paper on the development of services for personality

disorders, the details of which are outlined in this issue. It is estimated that a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder features in up to 20 per cent of clinical presentations to mental health outpatient clinics in Ireland, and the lack of dedicated services for these patients is leaving them without access to treatments that would greatly support their quality-of-life, and pushing them further to the margins of our health service and society as a whole, the College said.

The College has also just published a position paper on assisted dying, an issue which will shortly be the focus of a Special Oireachtas Committee set up to examine the Dying with Dignity Bill (2020). A naturally controversial topic, opinions are mixed among the general public and medical profession about the best approaches in this area. The College has warned that allowing doctors to assist in the suicide of their patients represents a fundamental and irreversible shift in medicine’s philosophy and practice, and that it is not compatible with good medical care. The College further warns that its introduction in Ireland could place vulnerable patients at risk: “Euthanasia creates the risk that many people will die from treatable psychological distress and mental illness.” See page 3 for more details.

All-in-all, this is a packed edition of Update that should hopefully prove interesting and useful to all our readers.

Thank you to all our expert contributors for taking the time to share their knowledge and advice for the betterment of patient care.

We always welcome new contributors and ideas and suggestions for future content, as well as any feedback on our content to date. Please contact me at priscilla@mindo.ie if you wish to comment or contribute an article. ■

1 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

Editor Priscilla Lynch priscilla@mindo.ie

Sub-editor Emer Keogh emer@greenx.ie

Creative Director Laura Kenny laura@greenx.ie

Advertisements Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

Administration Daiva Maciunaite daiva@greenx.ie

Update is published by GreenCross Publishing Ltd, Top Floor, 111 Rathmines Road Lower, Dublin 6 Tel +353 (0)1 441 0024 greencrosspublishing.ie

© Copyright GreenCross Publishing Ltd 2022

The contents of Update are protected by copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means – electronic, mechanical or photocopy recording or otherwise – whole or in part, in any form whatsoever for advertising or promotional purposes without the prior written permission of the editor or publisher.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in Update are not necessarily those of the publishers, editor or editorial advisory board. While the publishers, editor and editorial advisory board have taken every care with regard to accuracy of editorial and advertisement contributions, they cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions contained.

GreenCross Publishing is owned by Graham Cooke graham@greenx.ie

2

Contents 03 College of Psychiatrists of Ireland position paper on assisted dying 04 College of Psychiatrists of Ireland position paper on services for personality disorders 05 Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD): An overview 08 College of Psychiatrists Winter Meeting coverage 11 A recap on schizophrenia 13 Progressive supranuclear palsy: An update 15 The common manifestations of anxiety disorders 17 Irish hospitals join European network of expert centres for rare neurological diseases

Diagnosis and treatment of bipolar affective disorder 20 Migraine: Medicationoveruse and medicationoveruse headache 24 An update on mindfulness: What is the evidence? 27 An overview of motor neurone disease 30 Combating neurophobia in Irish healthcare 34 The psychiatric impact of post-Covid-19 syndrome 36 An update from FutureNeuro SFI Research Centre 38 Expert exercise prescriptions for Parkinson’s disease

18

College of Psychiatrists of Ireland warns against introduction of assisted dying legislation in Ireland

Euthanasia is illegal in Ireland and the Irish Medical Council forbids participation in the deliberate killing of a patient. Other jurisdictions have moved to permit euthanasia in one form or other, with some more restricted and others very broad.

In Ireland, as in many other countries, the question is increasingly arising as to whether doctors may become involved in ending patients’ lives, either directly (euthanasia) or indirectly (physician-assisted suicide), together known as PAS-E. A related question is whether the law should ever compel them to do so.

Not surprisingly, this is a controversial topic and opinions are mixed among the general public and the medical profession about the best approaches in this area.

The issue will shortly be the focus of a Special Oireachtas Committee set up to examine the Dying with Dignity Bill (2020).

There are medical, psychological, and social implications to the direct and indirect ending of the lives of seriously ill and vulnerable people. Allowing doctors to assist in the suicide of their patients represents a fundamental and irreversible shift in medicine’s philosophy and practice according to the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland.

The College has warned that PAS-E is not compatible with good medical care and that its introduction in Ireland could place vulnerable patients at risk. “Euthanasia creates the risk that many people will die from treatable psychological distress and mental illness.”

Acknowledging the psychological distress often associated with the end of life, and because of the unintended consequences of permitting euthanasia and assisted suicide,

the College recently (20 December 2021) published a position paper on this area which sets out what it sees as some key issues regarding the introduction of assisted dying in Ireland. This document was prepared by the Human Rights and Ethics Committee of the College and approved by the College Council in September 2021.

“In keeping with national and international experts in palliative care we believe that euthanasia is not necessary for a dignified death and on the contrary may diminish personal dignity.”

Key issues outlined by the College in its paper include that:

Assisted dying is contrary to the efforts of psychiatrists, other mental health staff, and the public to prevent deaths by suicide.

It is likely to place vulnerable people at risk – many requests for assisted dying stem from issues such as fear of being a burden or fear of death rather than from intractable pain. Improvements in existing services should be deployed to manage these issues.

While often introduced for patients with terminal illness, once introduced assisted dying is likely to be applied more broadly to other groups, such that the numbers undertaking the procedure grow considerably above expectations;

The introduction of assisted dying represents a radical change in Irish law and a long-standing tradition of medical practice, as exemplified in the prohibition of deliberate killing in the Irish Medical Council ethics guidelines.

Commenting, Consultant Liaison Psychiatrist Dr Eric Kelleher, a member of the College and contributing author to the position paper on assisted dying, said: “We are acutely aware of the sensitivity of

this subject, and understand and support the fact that dying with dignity is the goal of all end of life care. Strengthening our palliative care and social support networks makes this possible. Not only is assisted dying or euthanasia not necessary for a dignified death, but techniques used to bring about death can themselves result in considerable and protracted suffering.

“Where assisted dying is available, many requests stem, not from intractable pain, but from such causes as fear, depression, loneliness, and the wish not to burden carers. With adequate resources, including psychiatric care, psychological care, palliative medicine, pain services, and social supports, good end of life care is possible,” he said.

Dr Siobhan MacHale, Consultant Liaison Psychiatrist, a member of the College and contributing author to the position paper on assisted dying, added: “Once permitted in a jurisdiction, experience has shown that more and more people die from assisted dying. This is usually the result of progressively broadening criteria through legal challenges because, if a right to assisted dying is conceded, there is no logical reason to restrict this to those with a terminal illness.”

She continued: “Both sides of this debate support the goal of dying with dignity, but neither the proposed legislation nor the status quo (as evidenced by both clinical experience and the power of this debate) is sufficient. It is imperative for the Irish people to continue to demonstrate leadership as a liberal and compassionate society in working together to achieve this.”

The full position paper is available at www.irishpsychiatry.ie.

3 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

New CPI position paper on personality disorder services

The College of Psychiatrists (CPI) recently published a new position paper titled Develop–ment of Services for Treatment of Personality Disorder in Adult Mental Health Services

It is estimated that a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder features in up to 20 per cent of clinical presentations to mental health outpatient clinics in Ireland.

A lack of dedicated services for people with personality disorders is leaving individuals diagnosed without access to treatments that would greatly support their qualityof-life, and pushing them further to the margins of our health service and society as a whole, the College said.

To begin a conversation toward establishing a more robust system of care for those affected by these disorders, a dedicated special interest group within the CPI put together this position paper, which identifies the level of unmet need in Ireland and makes recommendations for the future development and improvement of services.

Often further co-occurring mental health needs present, such as addiction, depression or anxiety, with those with personality disorder having a higher likelihood of emergency presentations and suicidality. The wider effects on people’s lives and on society as a whole can be also seen: Higher health service utilisation, poorer physical health outcomes, interactions with the criminal justice system, and greater economic toll. Delivering evidence-based treatments as a first-line for people with personality disorders would help to alleviate significant harm for both the individual and costs for health services, the paper says.

The position paper looks to begin with the following four key actions:

1. Identify the prevalence and level of unmet need of personality disorders in Ireland, with a focus on adult mental health services.

2. Review the scientific evidence on treatments for personality disorders and international treatment guidelines.

3. Establish the current level of service provision for personality disorder in Ireland.

4. Make recommendations to the HSE and CPI for the further development of personality disorder treatment in Ireland.

Existing services

In support of their aim of improving service provision, the Personality Disorder Special Interest Group has previously conducted a survey of College members, which sought to identify existing service offerings in adult mental health services for the treatment of personality disorders. Only 57 per cent of respondents stated that they had an evidencebased treatment in their service while a worrying 9 per cent of respondents were unaware of any specific interventions offered. Nearly half of respondents identified a lack of resources as the main obstacle to delivering an appropriate service for people with personality disorder.

The group also hopes for greater collaboration with service users in the design and delivery of services that support patient autonomy and choice, hope, and trusting therapeutic relationships between patient and clinician.

Despite the existence of several wellevidenced and cost-effective treatments for personality disorders, the newest mental health policy for Ireland, ‘Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone’, which was launched in 2020, does not specifically refer to pathways or services for those with personality disorders at all.

To address the concerning lack of treatments for personality disorders on offer in Irish mental health services, the paper makes the following recommendations:

Implementation of the recommendation of ‘A Vision for Change’ to provide both localised

and specialist services including evidencebased treatments of people with personality disorders and to further commission a National Clinical Programme for personality disorders to further develop the provision of services within Ireland.

The establishment and funding of specialist consultant medical psychotherapist posts that will in turn provide the expertise and leadership necessary to manage specialist personality disorder services.

To ensure the expectation that services for people with personality disorders will be offered throughout the country and not just in a few locations or pilot sites.

To develop a wider educational programme about personality disorders, broadening knowledge and awareness of personality disorder within the health service more broadly and also associated agencies such as social care and the criminal justice system.

The establishment of a mechanism that would include the patient voice in the development of training and services.The full paper can be accessed at www.irishpsychiatry.ie

Background

The Personality Disorders Special Interest Group was established by the College for members interested in the aetiology, treatment and management of personality disorders in adults and emergent personality disorders in adolescents. It aims to promote learning and information sharing on the management of personality disorders, to help support educational and training initiatives for clinicians working with personality disorders, and to advocate for better service provision for adults with a personality disorder or emergent personality disorders amongst adolescents. Its Chair is Dr Paul Matthews.

For more information about the Personality Disorders Special Interest Group, please email hmurray@irishpsychiatry.ie.

Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022 | Psychiatry and Neurology 4

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD): An overview

AUTHOR: Theresa Lowry-Lehnen, RGN, GPN, RNP, PhD, Clinical Nurse Specialist and Associate Lecturer Institute of Technology Carlow

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is a complex personality disorder often detected with other affective and personality disorders.1 Affected people have unstable and intense emotions and a distorted image of ‘self’. NPD is a disorder in which the individual is overly preoccupied with vanity, prestige, power, and personal adequacy, lacks empathy, and has an exaggerated sense of superiority. This excessive sense of importance and superiority, combined with a preoccupation with success and power do not reflect real self-confidence. The individual often has a deep sense of insecurity and fragile self-esteem. 3

The legend of Narcissus, a character in Greek mythology from which the term narcissism derives (Narcissus fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water), has become one of the most prototypical myths of modern times. However, narcissism has become a defining feature of the modern era and interest in the concept has captured the imagination of the public, media and literature. This has been paralleled by a growing body of academic interest and empirical research, particularly in the fields of psychology, social science and cultural studies. Within psychiatry, the concept of narcissism has evolved from early psychoanalytic theorising to its official inclusion as a personality disorder in psychiatric nomenclature.6

Extensive literature regarding aetiological theories of narcissism exists, predominantly from psychoanalytic and psychodynamic perspectives, but more recently from social learning theory and attachment research.6 The widespread use of the concept of pathological narcissism

as a distinct personality type by clinicians influenced by psychoanalysts such as Kernberg and Kohut, and psychologists such as Millon, led to the introduction of NPD into the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III in 1980. The NPD construct was further refined and modified as it evolved through DSM-III-R (1987) and DSM-IV (1994) on the basis of the empirical findings of an increasing number of psychological studies identifying narcissism as a personality trait. These shifts in the diagnostic criteria for the disorder however were criticised for losing some of the more dynamic variables present in its phenomenological manifestations. The diagnostic criteria for NPD in DSM-5 are focused on characteristics of grandiosity and entitlement rather than more vulnerable manifestations of the disorder. However, it is generally accepted that at least two subtypes or phenotypic presentations of pathological narcissism can be differentiated: Grandiose or overt and vulnerable or covert narcissism.6

Presentation of NPD

DSM-5 describes NPD as a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, fantasy or behaviour, need for admiration and lack of empathy, beginning by early adulthood and indicated by at least five of the following. The individual: 2

Has a grandiose sense of self-importance, eg, exaggerates achievements, expects to be recognised as superior without actually completing the achievements;

Is preoccupied with fantasies of success, power, brilliance, beauty, or perfect love;

Believes that they are ‘special’ and can only be understood by or should only associate with other special people or institutions;

Requires excessive admiration;

Has a sense of entitlement, such as an unreasonable expectation of favourable treatment or compliance with his or her expectations;

Is exploitative and takes advantage of others to achieve their own ends

Lacks empathy and is unwilling to identify with the needs of others;

Is often envious of others or believes that others are envious of them;

Shows arrogant, haughty behaviours and attitudes.

Narcissism is a trait, but can also be a part of a larger personality disorder. Not every narcissist has NPD, because narcissism is a spectrum. People who are at the highest end of the spectrum are those

5 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

NPD is a disorder in which the individual is overly preoccupied with vanity, prestige, power and personal adequacy, lacks empathy, and has an exaggerated sense of superiority

that are classified as NPD, but others with narcissistic traits may fall on the lower end of the narcissistic spectrum. While everyone may show occasional narcissistic behaviour, true narcissists frequently disregard other people or their feelings and also do not understand the effect that their behaviour has on other people. 5

Narcissists can initially be very charming and charismatic and don’t always show negative behaviour straight away. Narcissists like to surround themselves with people who feed into their ego and build relationships to reinforce their ideas about themselves, even if these relationships are superficial. 5

People with NPD have difficulty handling perceived criticism and can:

Become impatient or angry when they don’t receive special treatment;

Have significant interpersonal problems and easily feel slighted;

React with rage or contempt and belittle others to make themselves appear superior;

Have difficulty regulating emotions and behaviour;

Experience major problems dealing with stress and adapting to change;

Feel depressed and moody because they fall short of perfection;

Have secret feelings of insecurity, shame, vulnerability and humiliation.

Risk factors

The aetiology of NPD is not fully understood. However, as with personality development and other mental health disorders, the causes of NPD are likely complex and multifaceted and NPD may be linked to environment, genetics and neurobiology.7 Traits such as aggression, reduced tolerance to distress, and dysfunctional affect regulation are prominent in people with NPD.

Developmental experiences, negative in nature, being rejected as a child, and a fragile ego during early childhood may contribute to the occurrence of NPD in adulthood. In contrast, excessive praise, including the belief that a child may have extraordinary abilities, may also lead to NPD.1 ‘Grandiose’ and ‘vulnerable’ narcissism are two different types of narcissism that have common traits, but which can arise from different childhood experiences. People with grandiose narcissism were most likely treated as if they were superior or better than others during childhood and these expectations can follow them into adulthood. Those with grandiose narcissism are aggressive, dominant, and exaggerate their importance. They are very self-confident, lack sensitivity and tend to be elitist. 5 Vulnerable narcissism is usually the result of childhood neglect or abuse. People with this behaviour are more sensitive and narcissistic behaviour helps to protect them against feelings of inadequacy. Even though they go between feeling inferior and superior to others, they feel offended or anxious when other people do not treat them as if they are special. 5

Pathological narcissism

The more encompassing term ‘pathological narcissism’ has been used to better reflect personality dysfunction that is fundamentally narcissistic, but allows for both grandiose and vulnerable aspects in its presentation.4 Individuals with pathological narcissism express many difficulties of identity and emotion regulation within the context of significant interpersonal relationships. While previous research has established some of the interpersonal impact on those in a close relationship with someone exhibiting traits of pathological narcissism, no qualitative studies existed until recently. In 2020, a significant qualitative study on living with pathological narcissism took place, and involved 2,219 relatives of people reportedly high in narcissistic traits. 3 Participants in this

study described ‘grandiosity’ in their relative as the need for admiration, displaying arrogance, entitlement, envy, exploitativeness, grandiose fantasy, selfimportance, interpersonal charm, and a lack of empathy. They also described ‘vulnerability’ of their relative as contingent self-esteem, hypersensitivity and insecurity, affective instability, emptiness, rage, devaluation, hiding the self, and having a victim mentality. Grandiose and vulnerable characteristics were commonly reported together by 69 per cent of respondents in this study. Participants also described perfectionistic, vengeful, antisocial, suspicious, and paranoid features in the individual. Living with a person with pathological narcissism can be marked by experiencing a person who shows large fluctuations in affect, oscillating attitudes, and contradictory needs, and these findings have implications for diagnosis and treatment in that the initial spectrum of complaints may be misdiagnosed unless the complete picture is understood. 3

Diagnosis

A sense of entitlement is common in people with narcissism. They often believe that they are superior to others, deserve special treatment, people should be obedient to their wishes, and they may become rude or abusive when they do not receive the treatment they feel they deserve. Manipulative or controlling behaviour is another common trait. A narcissist will at first try to please and impress, but eventually, their own needs will always come first. When relating to other people, narcissists will try to keep people at a certain distance in order to maintain control and exploit others to benefit themselves. One of the most common signs of a narcissist is a need to boost their ego, to feel appreciated and receive validation from others. The narcissist is unwilling or unable to empathise with the needs, wants, or feelings of other people. 5 They commonly have an expectation that others will automatically go along with what he or she wants and have an inability to

Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022 | Psychiatry and Neurology 6

recognise or identify with the feelings, needs, and viewpoints of others. Envy of others or a belief that others are envious of them and hypersensitivity to insults whether real or imagined, criticism, or defeat, possibly reacting with rage, shame, and humiliation is common. 5

Generally, narcissists do not recognise their disorder or seek help as it does not fit the self-image they have of themselves, and they may need the encouragement of others to seek professional help. Diagnosis of NPD typically is based on signs and symptoms, a physical exam, a thorough psychological evaluation that may include filling out questionnaires, and the NPD criteria as listed in DSM-5 8

Obtaining an accurate history can be somewhat challenging with NPD, given the variability of the presentation. Individuals can be well related and high functioning, but they can also be aggressive and challenging patients.1 The diagnosis of NPD like other personality disorders requires evaluation of long-term patterns of functioning. A careful evaluation of the different aspects of a person’s life and an understanding of the person’s childhood development can assist in the evaluation and diagnosis of NPD.1

A standard psychiatric interview is often used to make a diagnosis of personality disorders. Other instruments may measure the severity of NPD, such as the five-factor narcissism inventory that looks at the five aspects of general personality. There are approximately 148 questions on the fivefactor inventory. Another measure that may be useful is the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. NPD is usually present with other mood disorders. Once a diagnosis is established, it is important to discuss the diagnosis because of several challenges that will be present. It is equally important to treat ongoing symptoms of co-occurring affective disorders.1

Treatment options

No standardised pharmacological or psychological treatment has been

established for people with NPD and there is no effective, known cure.1 Psychotherapy is often recommended, which helps the patient better understand their problems. This may bring about a change in their attitudes, resulting in better behaviour. Psychotherapy may involve cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), family therapy or group therapy. CBT helps the patient

including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs) and serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), have been used. Risperidone, an antipsychotic, has shown benefit in some patients and mood stabilisers such as lamotrigine. The prognosis depends on the severity of the disorder and the degree to which people who seek treatment recognise the problems within themselves, and aim to change the maladaptive aspects of their personality.

identify negative beliefs and behaviours, and replace them with healthy and positive ones. Psychotherapy aims to help patients build their self-esteem and acquire realistic expectations of themselves and other people. For some of the more distressing aspects associated with NPD, medication may be required. Antidepressants,

References

1. Mitra P, Fluyau, D. (2021). Narcissistic personality disorder. Available at: www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556001/

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington

3. Day N, Townsend M, Grenyer B. (2020). Living with pathological narcissism: a qualitative study. Bord Personal Disord Emot Dysregul 7, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40479-020-00132-8

4. Russ E, Shedler J. (2013). Defining narcissistic subtypes. In: Ogrodniczuk JS, editor. Understanding and treating pathological narcissism: American Psychological Association; 2013. p. 29-43

5. Brennan D. (2020). Narcissism:

Living with somebody who has NPD Family members and close contacts of people with NPD often describe them as controlling, egotistical, and dissatisfied with what anybody around them does. No matter what happens, the narcissist will blame others and make them feel guilty for their problems. They are described as having short fuses, losing their temper at the slightest provocation, or turning their backs and giving people the ‘silent treatment’. Some can be physically and sexually abusive. The emotional and physical damage caused by somebody with NPD can be severe and learning to become more confident and assertive can help protect those living with a person with NPD from long-term harm. 3

Symptoms and signs. In WebMD. Available at: www.webmd.com/mentalhealth/narcissism-symptoms-signs

6. Yakeley J. (2018). Current understanding of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. B J Psych Advances, 24 (5), 305-315. doi: 10.1192/bja.2018.20

7. Mayo Clinic. (2021). Narcissistic personality disorder. Symptoms and causes. Available at: www.mayoclinic.org/ diseases-conditions/narcissistic-personalitydisorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20366662

8. Mayo Clinic. (2021). Narcissistic personality disorder. Diagnosis and treatment. Available at: www.mayoclinic. org/diseases-conditions/narcissisticpersonality-disorder/diagnosis-treatment/ drc-2036669 0

7 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

No standardised pharmacological or psychological treatment has been established for people with NPD and there is no effective, known cure

College of Psychiatrists of Ireland, Winter Conference, virtual, 4-5 November 2021

ALL REPORTS BY VALERIE RYAN

ALL REPORTS BY VALERIE RYAN

Service

capacity for managing eating disorders to be ‘exceeded’ for some time to come

The disproportionate impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on people at risk of eating disorders and the pressures of a spike in referrals and the volume of people seeking care in outpatient and acute inpatient settings, were underlined by leading consultant psychiatrists in the field at the latest Winter Conference of the College of Psychiatrists of Ireland (CPI).

The Irish experience of clinicians reporting high volumes in outpatient clinics during the pandemic has been in line with international health services.

“But even with adaptations, service capacity for assessment and treatment is going to be exceeded for some time,” Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and Clinical Lead of the HSE Child and Adolescent Regional Eating Disorder Service (CAREDS) for Cork and Kerry, Dr Sara McDevitt, told conference attendees.

“Telehealth has been suitable for some aspects of care but certainly not all. Active waiting is now an essential part of what we do. And this has had a huge strain on doctor-patient relationships,” she said during the session on ‘Eating disorder care in a changed landscape – what have we learned toguide our next steps?’

Prior to the pandemic, services were confident they could manage referral, assessment, and treatment in a timely manner.

However, timelines have worsened over the past six months. Services did not have the capacity to take on the large volumes of people immediately, she said.

Dr McDevitt’s comments on the impact of Covid-19 and a large increase in the number of presentations were echoed by Consultant Liaison Psychiatrist, Dr Siobhan MacHale, Associate Clinical Professor, RCSI, who outlined the impact of the pandemic on the inpatient setting of an acute hospital – Beaumont Hospital in Dublin. Dr MacHale, presenting on eating disorder management in the general hospital, referred to a large increase in eating disorder admissions noted during 2021.

The acute hospital services were not just for patients presenting with eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, avoidantrestrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, but also the impact of, for example, obesity in terms of patients’ presentations and the impact of their overall health journey. Non-specified eating disorders were also seen by the service.

Each of these required a slightly different approach. But the component that brought them into an inpatient setting was where the medical consequences of their eating disorder resulted in significant malnutrition and/or metabolic disturbances.

About two-thirds of patients would have significant cardiac complications at the time of presentation to the hospital.

She recommended the need to follow the MARSIPAN (Management of Really Sick Patients with Anorexia Nervosa) guidelines, which were about to be updated, originally developed by a multi-professional group working in the field due to the number of patients with anorexia nervosa who had been presenting in hospitals and dying within a number of days.

Up to 2017, she told College members, the service was seeing nine to 12 cases of anorexia nervosa per year, until 2020 when there was a significant drop to six admissions. However, 2021 had triggered a rapid escalation reaching 21 admissions in the first 10 months, on extrapolated data, with 24 expected during the year.

She stressed the challenges for the services in the face of increased presentations

Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022 | Psychiatry and Neurology 8

including resource difficulties and the impact of Covid-19, which had reduced staff availability.

Also during the Winter Conference, results from a study by Dr Jahan Khan and

colleagues at St Patrick’s Mental Health services in Dublin, “clearly indicate that the majority of patients attending the eating disorder service were negatively impacted by the pandemic,” with many reporting worsening eating disorder symptoms.

Their study, presented as part of the NCHD poster section, included all adult patients attending the eating disorder service during the year before the Covid-19 pandemic. They believed a follow-up study would be helpful to establish long-term impact.

Recruitment and retention plan crucial for expansion of specialty of psychiatry

President of the CPI, Dr William Flannery, re-iterated a call for over 800 consultant psychiatrists to be appointed in psychiatry by 2030, and urged publication of a crucial draft HSE/National Doctors Training and Planning (NDTP) unit plan for recruitment retention, in his opening remarks to the College’s Winter Conference 2021.

Speaking at the meeting, which took place on 4-5 November on a virtual basis, Dr Flannery referred to the recommendations for additional consultants, outlined in the NDTP unit medical workforce planning report on the specialty of psychiatry, and pointed out that progress has been slow.

He added that the document in train on recruitment and retention would be crucial to “the challenges we all face in the workplace”.

Training is the core of the College’s remit and although costing an estimated €1.9 million a year to fund adequately, he advised members that the College was due to receive €1.3 million for training which had represented an increase on previous funding.

On the Mental Health Act, Dr Flannery said it had to be amended and was currently with the Attorney General’s office. The Law Committee of the College was due to meet

to identify four or five key areas from the College’s perspective.

He complimented the Faculty of Medical Psychotherapy for its position paper, endorsed by the College. “That position paper is the development of services for treatment of personality disorder in adult mental health services. So now we have a position paper, the College can use this to get the direction we want,” said Dr Flannery.

Dr Flannery also paid tribute to the work of colleagues, who had various roles in policies and operations, for their hard work and for working with him.

Preventive measures urged to safeguard staff and patients in psychiatric settings

A need for preventive measures and improved reporting to safeguard staff and patients from violent incidents in psychiatric workplace settings has been highlighted in separate NCHD studies, presented at the latest Winter Conference of the CPI.

‘Zero violence or zero seclusion. Which is more acceptable in our hospitals?’, aimed to determine the number, nature, and characteristics of violent incidents and other incidents in a secure forensic hospital in Ireland.

Conducted at the Central Mental Hospital (CMH), Dublin, by Dr Kezanne Tong and colleagues, a total of 320 incidents were recorded between March 2019 and August 2021.

Since March 2020, the researchers observed an upward trend in the number of physical violence incidents perpetrated by patients. The number of incidents of actual physical assault had also increased during the study period.

They noted that the current lack of

admission beds in psychiatric services in Ireland, together with the very limited numbers of psychiatric ICU beds, “likely means that patients may be more unwell by the time they are admitted.”

In turn, this could have an effect on, firstly, the proportion of admissions that were involuntary, and, secondly, on the rates of seclusion and restrictive practice, as patients were more unwell on admission.

Restrictive practices must be used in accordance with the law, but were necessary

9 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

at times to prevent serious harm to patients and staff in psychiatric hospitals, according to the research. Any review of mental health legislation or the code of practice in relation to restrictive practice “must reflect on the

Westmeath Mental Health Services, and Dr Elaine Walsh, Mayo Mental Health Services, ‘Experiences of, and attitudes to, the reporting of violence in the workplace by mental health care staff’, recommended

sense of futility amongst staff; more than half feeling that violent incidents are preventable in the first instance and 70 per cent feeling that reported incidents are not properly investigated.”

The study found that 91 per cent of 67 respondents to the survey reported verbal abuse; 31.3 per cent recorded physical assault; 14.9 per cent had suffered sexual violence; and a further 13.4 per cent experienced racial harassment in a 24-month period. “A staggering 4.5 per cent of these reported that violence occurred daily.”

primary need for the safety of staff and patients in psychiatric hospital settings”.

A separate study considered the issue of reporting levels of violent incidents in psychiatric settings.

Presented by Dr Joanne Fegan, Longford/

further work was needed in the prevention of workplace violence as well as improvements in reporting and investigating of incidents when they did occur.

It was clear from the response to an online survey that: “There is a high degree of non-reporting of violence with an apparent

It was not unreasonable to speculate that the recorded figure of 6,690 violence incidents in 2018 and 2019, from the State Claims Agency, fell short of the reality as this figure represented the collation of the official National Incident Management System forms that were filled in by staff regarding violent incidents, added the study.

Large scale trials considering therapeutic use of low-dose psychedelics in depression

Latest trials and research into therapeutic use of controlled low-dose psychedelics, such as psilocybin, ketamine, and substituted amphetamines in mainstream psychiatry, was outlined at the CPI Winter Conference.

A session on ‘Ketamine and psychedelics in psychiatry: Pipers at the gates of dawn?’ highlighted new research into the psychopharmacology and possible therapeutic potential of psychedelics for treatment of resistant psychiatric conditions.

College members heard of preclinical studies that were elucidating neurobiological mechanisms, which may underlie their antidepressant effects.

Prof Andrew Harkin, Associate Professor of Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Trinity College Dublin (TCD), detailed their

psychopharmacology, brain connectivity, and “new research in neuroscience that is prompting a resurgence in the potential of these drugs for the clinic”.

On the pharmacology of ketamine, he said that at some anaesthetic doses, the antidepressant actions of the drug was noted.

A series of trials where these observations had been reported included published results of a trial of 18 patients, with treatmentresistant major depressive disorder, who showed robust and rapid response to intravenous ketamine for up to a week following infusion of a sub-anaesthetic dose.

These studies had prompted a lot of drug discovery and development effort. This had culminated in the US FDA approval, in March 2019, of the intra-nasal delivery of esketamine for treatment-resistant depression.

Prof Veronica O’Keane, TCD and Tallaght Psychiatry Services, discussed tryptamines in her talk on ‘Psilocybin as a treatment for depression and as a way to look through the windows of consciousness to the connected brain’.

She said studies focusing on psilocybin had exceeded those of other psychedelics. Most studies worldwide were looking at psilocybin as a treatment for depression.

Details of the first randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of psilocybin for the treatment of resistant depression by the Tallaght Psychiatry Service were presented.

Prof Declan McLoughlin, TCD and St Patrick’s University Hospital, Dublin, followed up with a discussion on: ‘Is there a role for ketamine in routine clinical practice?’

Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022 | Psychiatry and Neurology 10

In turn, this could have an effect on, firstly, the proportion of admissions that were involuntary, and, secondly, on the rates of seclusion and restrictive practice, as patients were more unwell on admission

A recap on schizophrenia

AUTHORS: Dr Niall Duffy, Registrar in Psychiatry, Saint John of God Hospital, Stillorgan, Co Dublin; and Dr Stephen McWilliams, Associate Clinical Professor, School of Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin, and Consultant Psychiatrist, Saint John of God Hospital

(two or more voices discussing the individual among themselves);

CASE REPORT

Johnny is a 28-year-old man referred by his GP to a psychiatric crisis assessment team. It seems his family are concerned about some of his beliefs and recent behaviours. He has been working from home since the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions began in early 2020. A few months ago, Johnny started to hear voices of his colleagues telling him they believe his university qualifications to be fake and that he will never amount to anything in life. Lately they have accused him of fraud and have threatened to inform the guards. These voices are clearly heard out loud and have become relentless; he is understandably frightened by them.

Schizophrenia is characterised by a fundamental distortion in several mental modalities including perception, thought, belief, self-experience, cognition, affect and volition. It carries a lifetime risk of around 1 per cent and presents most commonly in late adolescence to early adulthood. The incidence in males and females tends to be equal, but onset tends to be earlier in males. For a diagnosis of schizophrenia to be made, the psychosis cannot be attributable to mania or depression, an organic brain disease, or intoxication with or withdrawal from substances.

The causes of schizophrenia have been studied for many decades and appear to encompass several different risk factors including genetics, developmental issues and environmental influences (such as cannabis and other illicit substances). Combinations of genes seem to make individuals more susceptible to developing schizophrenia, with family and twin studies highlighting an increased risk where a first-degree relative has been diagnosed. But not everyone with

He starts to worry that his colleagues are monitoring his movements via computer surveillance and he fears for his safety. He covers his webcam with tape and keeps his phone switched off, making it difficult for his employers to contact him. He stops attending occasional face-to-face meetings in case his colleagues use this as an opportunity to plant a bug on him. Soon he stops leaving the house completely. His parents finally persuade him to attend the crisis team and the psychiatrist forms the view that he is experiencing a first episode of psychosis suggestive of emerging schizophrenia. Johnny agrees to be admitted to a local psychiatric hospital for assessment and treatment.

(d) Persistent delusions of other kinds, (delusions being fixed, false beliefs that cannot be explained by religious or cultural contexts);

(e) Persistent hallucinations in other modalities;

(f) Thought disorder (where the link between one thought and the next is disrupted);

(g) Catatonic behaviour, such as mutism or posturing;

(h) Negative symptoms, with a change in the quality of an individual’s personal behaviour, which can be remembered as the ‘5As’:

Affective flattening (poor eye contact, reduced facial expression);

Alogia (poverty of speech, latency or delay in the response to questions);

Avolition (lack of drive with evidence of emotional withdrawal);

these risk factors will develop schizophrenia. Indeed, the ‘stress-vulnerability’ model dictates that increased levels of pressure in everyday life, combined with risk factors, may increase the likelihood of an emerging psychotic episode.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of schizophrenia, using criteria outlined in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), is based on clinical judgement in the context of a clear understanding of the symptoms comprising specific criteria. Specifically, at least one of (a), (b), (c) or (d) below – or two of (e), (f), (g) or (h) below – must be evident for the diagnostic criteria to be met:

(a) Thought echo, insertion, withdrawal or broadcast;

(b) Delusions of control, impulse or passivity (ie, of being under the control of external forces);

(c) Auditory hallucinations, which are usually running commentary (describing the individual’s behaviour) or third-person

Anhedonia/asociality (reduced interests or activities, and impaired relationships with family members or friends);

Attention deficits (social inattentiveness).

In the ICD-10, the psychotic symptoms must be present most of the time for a period of at least one month. If the symptom criteria are met, but last for less than a month, then schizophrenia should not be diagnosed initially. The ICD-10 categorises schizophrenia into nine different subtypes – paranoid, hebephrenic, catatonic, undifferentiated, post-schizophrenic depression, residual, simple, other and unspecified – however, these categories will soon be obsolete as we herald the ICD-11, which is due to be adopted into practice from January 2022. Here, the subtypes of schizophrenia are to be removed and replaced by groups of dimensional and longitudinal descriptors which allow a more individualised description of the presentation of the illness and its course over a period of time.

The symptoms of schizophrenia have generally remained unchanged in the ICD-11, with core symptoms involving persistent hallucinations,

11 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

persistent delusions, thought disorder and experiences of influence, passivity or control. A formal diagnosis will require at least two out of a total seven symptoms (one of which must be a core symptom) present for at least one month.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia using the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) differs somewhat, with an individual needing to meet a defined set of criteria in order to receive a diagnosis.

Treatment

The treatment of schizophrenia, like all other psychiatric disorders, follows a biopsychosocial approach. Treatment in an inpatient setting may be required with the first presentation of a psychotic illness and in more severe presentations, allowing access to robust multidisciplinary assessment and a calm environment with limited stimulus. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines are one among several trusted sets of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the treatment of schizophrenia. NICE recommends offering an oral antipsychotic in the first instance, with patient involvement as much as possible to provide information on efficacy and the potential sideeffect profile (noting that this may not always be possible where the presentation is severe).

Antipsychotic medications are divided into first-generation (FGA) and second-generation (SGA) varieties. Many FGAs have been available since the early 1950s and include haloperidol, zuclopenthixol, chlorpromazine and sulpiride. Common side-effects include sedation, weight gain, prolonged QTc, hyperprolactinaemia, and extrapyramidal signs (acute dystonia, akathisia, Parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia).

SGAs have mostly been used since the early 1990s and include olanzapine, risperidone, paliperidone, quetiapine, amisulpride and aripiprazole. Some SGAs have a greater metabolic side-effect burden (exceptions being amisulpride and aripiprazole) leading to an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. Clozapine first became available in the 1970s and remains the most efficacious SGA. It is reserved for cases of treatment-resistant

schizophrenia due to the potentially fatal side-effect of agranulocytosis, which ultimately quelled its widespread use until a Clozapine Patient Monitoring Service (CPMS) was established in the 1990s. The CPMS regularly monitors the white cell count of every clozapine patient and ensures that it is safe to use. Other potential side-effects include sedation, weight gain, constipation, hypersalivation, cardiomyopathy, and seizures.

Both FGAs and SGAs are effective in the treatment of positive symptoms (experiences that are present when they should not be) such as delusions, hallucinations and thought disorder. According to the Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines, there is little evidence favouring either antipsychotic group in the treatment of negative symptoms (experiences that are not there when they should be), such as the 5As. Such symptoms strongly contribute to the poor functional outcome of some individuals with schizophrenia. However, there is emerging evidence for the use of cariprazine in the treatment of negative symptoms, with initial evidence showing it to be well tolerated. Common side-effects include mild-to-moderate akathisia and Parkinsonism, but there is limited evidence so far of any metabolic side-effect profile.

In general, the lowest possible dose of a single antipsychotic should be used in the first instance. Combinations of antipsychotics should only be considered if there has been inadequate response to individual antipsychotics including clozapine. Patients prescribed an antipsychotic should have regular evaluation of side-effects (for example, using the Glasgow antipsychotic side-effect scale) and frequent monitoring of physical health parameters including vital signs, ECG, weight, and blood tests (lipids, fasting glucose and HbA1c, WCC, U&E, LFTs, and prolactin). In severe psychosis with agitation in the inpatient setting, a rapid tranquilisation protocol, such as intramuscular olanzapine, lorazepam or combined haloperidol and promethazine, may be needed to reduce acute distress and minimise the risk of harm to self and others.

Psychosocial interventions include the use of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

for psychosis, patient and family psychoeducation, behavioural family therapy and programmes aimed at promoting longerterm recovery, such as the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP), to name a few.

Programmes to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) have demonstrated that earlier detection improves outcomes. Ultimately, schizophrenia is a relapsing and remitting illness and two-thirds of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis will have further episodes. Leucht and colleagues (2012) demonstrated that regular antipsychotic medication is protective against relapse in the short-, medium- and long-term. The risk of relapse and poorer outcomes are greater in those with a longer duration of untreated psychosis, a negative attitude towards treatment, a greater burden of side-effects and residual symptoms after treatment. Long-acting injections are a good option for those with frequent relapses due to non- or partialadherence to oral medication. Ultimately, with the correct tools and approach, it is realistic for an individual with schizophrenia to live a pleasurable and meaningful life.

So what happens to Johnny?

He is admitted voluntarily to his local psychiatric unit and assessed by the admitting doctor who recommends commencing a secondgeneration antipsychotic. Johnny is initially reluctant and appears sceptical, but soon begins to trust his treating team and ultimately takes the medication. His symptoms improve and he is offered CBT for psychosis, where he is gently challenged in relation to the delusional beliefs he has in relation to his colleagues. He attends occupational therapy, while family meetings allow for a well-rounded understanding of the challenges he encounters. Following a period of assessment, he is diagnosed with schizophrenia using the criteria outlined of ICD-10. He is discharged home after six weeks and regularly attends outpatient clinics for review. He also attends CBT on an outpatient basis. After a few months, he returns to work on a phased basis and reports feeling more comfortable around other people. He plans to commence a master’s degree next year. ■

References on request

Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022 | Psychiatry and Neurology 12

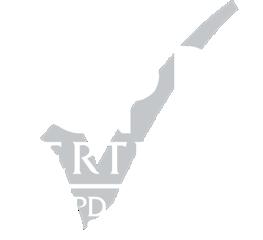

Progressive supranuclear palsy: An update

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition characterised by axial rigidity, oculomotor abnormalities, and cognitive impairment with prominent postural instability and early falls. Pathologically, PSP is characterised by aggregations of tau within the brain. New diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines have been developed in recent years, which have altered our understanding of PSP. There is no disease-modifying treatment for PSP currently although several agents are under investigation.

Epidemiology and aetiology of PSP

The mean age of onset of PSP is 63 years and progresses to death over approximately seven years, although some subtypes follow a slower course. Estimates of PSP prevalence vary considerably with rates of 5-6 per 100,000 commonly quoted. Estimates of the annual incidence of PSP range from 0.9-1.9 per 100,000.

PSP is typically a sporadic disorder, however, familial cases related to mutations in the MAPT gene as well as a handful of cases related to LRRK2 mutations have been identified, while genome-wide association studies have identified several risk loci of PSP.

Environmental risk factors have been identified related to geographic clusters of PSP. A PSP-like Parkinsonism identified in Guadeloupe has been associated with mitochondrial toxins in annonaceae fruit, while a high rate in an industrial region of northern France appears to relate to exposures to industrial metals.

Other potential risk factors include hypertension, lower levels of education, and rural living. The pathological hallmarks of PSP are microtubule-associated protein tau

aggregates affecting the brainstem and basal ganglia, spreading rostrally to involve the frontal and occipital lobes, and caudally to involve the dentate nucleus and cerebellum. These aggregates are composed of tau isoforms with four microtubule-binding repeats (4R-tau) in the form of neurofibrillary tangles, oligodendrocytic coils, and astrocytic tufts.

Clinical presentation

In their original 1964 paper, Richardson, Steele, and Olszewski described a syndrome of axial rigidity, oculomotor abnormalities, and cognitive impairment. While this so-called Richardson’s syndrome (RS) is the presentation most characteristic of PSP, a much wider range of presentations have been recognised. These variants include Parkinsonism (PSP-P), primary apraxia of gait (PSP-PAGF), corticobasal syndrome (PSP-CBS) and speech and language disturbance (PSP-SL). The 2017 MDS criteria for the diagnosis of PSP recognises eight distinct PSP phenotypes.

Gait and balance impairment are early, disabling, and dangerous symptoms in PSP. Typically, postural reflexes are markedly impaired and patients tend to fall backwards. People with PSP have a stiff, broad-based gait, with knees and trunk extended and arms slightly abducted (sometimes called a ‘gunslinger’ gait) while neck dystonia often produces retrocollis. Patients may pivot wildly when turning due to impaired insight and impulsivity.

Oculomotor abnormalities are a hallmark of PSP. Impairments of vertical saccades are an early finding with downgaze more prominently affected. Other findings include square-wave jerks (saccadic movements with occur during fixation), loss of convergence, and blepharospasm may be seen. Light

sensitivity is common and tinted glasses may help. An inability to look down can cause difficulty reading, walking, and eating (resulting in the ‘messy tie sign’).

Signs evident in the face may include reduced blink rate, frontalis overactivity, and vertical wrinkling of the forehead (the procerus sign) resulting in a troubled or surprised expression. Patients may have difficulty opening their eyes due to dystonia of the tarsal muscles (the common description, ‘apraxia of eyelid opening’, is a misnomer).

The speech disturbance of PSP is characterised by slow, effortful, and distorted speech sometimes referred to as ‘growling’ or ‘gravelly’, which is distinct from both the quiet, monotonous speech of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD) and the high-pitched, breathy voice of multiple system atrophy (MSA). Language impairment including non-fluent/ agrammatic progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech may be present.

Cognitive impairment in PSP is characterised by frontal lobe dysfunction. Impaired executive function with reduced speed of processing and mental agility, apathy, and spontaneous motor behaviours, such as palilalia and punding may occur. Impulsivity may result in patients attempting tasks they are unable to complete safely. Sleep disturbance is common in PSP with patients frequently describing difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep. REM-sleep behaviour disorder may occur, but is less frequent than in α-synucleinopathies.

Ancillary investigations

A diagnosis of PSP is made on clinical grounds; however, brain imaging can play a supportive role. Classically, brain MRI

13 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

AUTHORS: Dr Shane Lyons1, Dr Sean O’Dowd1, and Prof Tim Lynch 2

1. Neurology Department, Tallaght University Hospital, and 2. Dublin Neurological Institute, Mater Misericordiae University Hospital

demonstrates atrophy of the brainstem, particularly the midbrain. The ratio of pons to midbrain diameter is useful to differentiate PSP from other Parkinsonian disorders. The ‘hummingbird’ and ‘morning glory’ signs, on midsagittal and axial images, respectively, are seen in PSP, but lack sensitivity. The magnetic resonance Parkinsonism index (MRPI) is calculated by multiplying the pons areamidbrain area ratio (P/M) by middle cerebellar peduncle (MCP) width-superior cerebellar peduncle (SCP) width ratio (MCP/SCP) and helps to identify cases of Parkinsonism likely to evolve to PSP. PET imaging reveals decreased glucose metabolism in the midbrain early in the disease course while decreased metabolic activity in the caudate, putamen, and prefrontal cortex occur later. New PET imaging modalities using ligand which bind to the tau protein may enable earlier diagnosis or more accurate measurements of the progress of disease.

Treatment

A range of strategies are used to ameliorate symptoms and improve quality-of-life in PSP. Few randomised control trials exist in PSP, and treatment strategies are largely based on clinical experience and observational studies. In 2021 the CurePSP Centres of Care Network published a consensus statement on the management of PSP which provides helpful guidance on a range of treatment modalities (available here: www.frontiersin.org/ articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.694872/full).

The involvement of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) with experience in neurodegenerative disease is essential in treating PSP. Physiotherapy can be useful to maintain strength and improve balance and coordination. The selection of appropriate walking aids is important. Lightweight wheelchairs with a tilting mechanism to prevent falling out are preferred. Occupational therapy intervention for functional and domestic adaptation is helpful. Speech therapy support for communication including the use of alphabet boards, text-tospeech systems, and repetitive exercises play a role. SLT also provide important support for swallowing difficulties.

Appointing an enduring power of attorney

early in the disease course can simplify later decisions. The social and caring challenges are significant. Support from a range of sources including the hospital team, community services, and patient organisations such as the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Association (PSPA) is essential. Early involvement of palliative care in the MDT can be extremely helpful, especially with regard to the need for hospice care as well as the management of multiple complex symptoms.

Important pharmacological options to consider in PSP include:

Levodopa may help with bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor: 20-to-30 per cent of patients with PSP respond to levodopa. A target dose of 800-1200mg per day is usually recommended.

Amantadine, titrated to a maximum dose of 100mg tds, may be helpful for gait dysfunction but may have deleterious cognitive effects.

Liposomal coenzyme Q10 (100mg tds) provides a benefit to gait in a small proportion of patients and a trial is recommended.

Baclofen and benzodiazepines may be helpful for dystonia.

Melatonin can be useful for insomnia.

Cholinesterase inhibitors should be used only where there are pronounced amnestic deficits and otherwise are best avoided.

Botulinum toxin may be helpful for focal dystonia and for apraxia of eyelid opening, while injection of the parotid glands can be helpful for the control of sialorrhea.

Although no treatment currently exists to slow or arrest the course of PSP, a number of potential therapies are under investigation. Disappointingly, 2021 saw negative results for two trials of anti-tau monoclonal antibodies directed against the N-terminal of tau (gosuranemab and tilavonemab), however, further studies are ongoing, including monoclonal antibodies targeting alternative binding sites on the tau protein (UCB0107), agents which modify mitochondrial function (MP201) or lipid peroxidation (RT001), and antisense oligonucleotides to reduce the production of tau (NIO752).

A persistent challenge in trials of PSP, as in all neurodegenerative disease, is that by the

time a diagnosis is made with confidence significant neurodegeneration has occurred and prospects of effective treatment are diminished. The search for early and reliable biomarkers, either imaging or CSF-based, may allow early identification of cases and initiation of treatment at an earlier stage.

PSP care and research in Ireland

To tackle the lack of epidemiological data on PSP in Ireland an Irish multicentre epidemiological study, ‘The Leinster Tauopathy Study,’ is in preparation and hopes to begin recruiting participants in early 2022. The study brings together Irish expertise in atypical Parkinsonism from Dublin hospitals and will seek referrals of patients with a possible diagnosis of PSP or CBS and a home address in Leinster. The study aims to establish the prevalence and incidence of PSP and CBS in an Irish population and plans to establish a biobank of blood, DNA, and cerebrospinal fluid samples to facilitate future studies of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Developing an accurate picture of the population with tauopathies and their needs will help to inform future service provision. Also this month (January 2022), Tallaght University Hospital will become accredited as the only Irish site in the European Research Network for Rare Neurological Diseases (ERN-RND) as an expert centre for atypical Parkinsonism. This prestigious designation will allow patients to access a broader range of specialist expertise.

Conclusion

PSP is a complex, progressive, neurodegenerative condition which has an enormous impact on the daily functioning, quality-of-life, and social circumstances of patients and their families. Patients commonly present with axial rigidity, gaze abnormalities, and cognitive impairment, although a wide range of phenotypes are described. Although no disease-modifying treatment exists, a range of therapies may help manage the symptoms and complications of the condition. In Ireland we are developing services for patients with PSP and other atypical Parkinsonian disorders, as well as national and international research projects and collaborations.

Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022 | Psychiatry and Neurology 14

The common manifestations of anxiety disorders

AUTHORS: Dr Niall Duffy, Registrar in Psychiatry, Cluain Mhuire Service, Blackrock, Co Dublin; and Dr Stephen McWilliams, Clinical Associate Professor, School of Medicine, University College Dublin, and Consultant Psychiatrist, St John of God Hospital, Stillorgan, Co Dublin

CASE REPORT

Chloe is a 19-year-old female who presents to the emergency department (ED) stating that she feels like she is having a heart attack. A first-year student at a local university, she attended a class in a crowded lecture theatre earlier today and describes having felt nervous on arrival as she couldn’t find a seat near the back of the hall. Chloe’s friend is enrolled in the same course as her, but was off sick today. Chloe reports that she suddenly started shaking, experienced her heart racing, and became short of breath before developing pains in her chest. She describes feeling terrified, as though she was “going to die”. She recounts being escorted out of the lecture hall by a classmate and now feels embarrassed that such an incident happened in front of so many people. She is seen by the SHO in the ED, and has routine blood tests, a physical examination and an ECG, all of which prove normal. Chloe is discharged from the ED, only to return three days later with a similar presentation. She is tearful and expresses uncertainty regarding her future. This time, she is referred to the liaison psychiatry service for further assessment.

The American Psychological Association defines anxiety as “an emotion characterised by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes”, such as sweating, palpitations, dizziness, and shaking. All of us experience at least some anxiety in our lives, but clinically-significant anxiety that crosses the door of a GP surgery or psychiatric clinic must be severe enough to affect our everyday functioning and cause significant distress.

Anxiety disorders are common worldwide. A systematic review published in Brain and Behaviour in 2016 – well before the Covid-19 pandemic – demonstrated the prevalence of anxiety disorders to range from 4-to-25 per cent with higher rates in females, younger adults, those with chronic diseases and Euro/ Anglo subgroups. Anecdotally, we have seen patients presenting more frequently with anxiety symptoms to our hospital and outpatient clinics during the Covid-19 pandemic, with early data showing that more than one-in-four adults living in the Republic of Ireland screened positive for generalised anxiety disorder or depression during the initial lockdown of March 2020. Such figures have been replicated in the UK.

Anxiety disorders are diagnosed using the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10/ICD-11) or the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The year 2022 will see the adoption of the ICD-11, with the now-out-ofdate chapter on ‘Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders’ in the ICD-10 replaced by four groupings, namely:

1. Anxiety and fear-related disorders;

2. Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders;

3. Disorders specifically associated with stress; and

4. Dissociative disorders.

This article will focus on the ICD-11 disorder grouping of ‘anxiety and fear-related disorders’.

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is the first disorder in this group. It is characterised by marked anxiety symptoms that are present on most days over a period of several months. It manifests as either free floating anxiety,

such as a consistent feeling of apprehension, or an excessive worry about normal everyday events. The individual can present as restless or irritable, with poor concentration, disrupted sleep and autonomic arousal leading to, for example, palpitations, nausea and hyperventilation. Screening tools such as the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) can be helpful both in hospitals and primary care settings to establish the severity of anxiety symptoms over the previous two weeks.

The second disorder in this group is panic disorder which consists of recurrent panic attacks, namely intense, rapid-onset periods of extreme worry and physical symptoms such as palpitations, sweating, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness. An intense fear of imminent death can occur, while the individual may be preoccupied with the return of a panic attack and thus engage in avoidant behaviours to prevent further attacks.

Agoraphobia involves intense fear or anxiety when an individual is faced with a situation from which they perceive escape to be difficult. Common examples include crowded places away from home such as a busy shop, a marketplace, or public transport. Avoidance of these situations for fear of embarrassment is a prominent feature. Agoraphobia can present with the physical symptoms of panic disorder as outlined above.

Specific phobias include arachnophobia (fear of spiders), acrophobia (fear of heights), and claustrophobia (fear of confined spaces). They present with severe anxiety and fear when the individual is exposed to (or anticipates exposure to) the particular phobic object or situation. Such fear is significantly out of proportion to the actual risk or danger, and the individual avoids the object or situation wherever possible.

15 Psychiatry and Neurology | Volume 8 | Issue 1 | 2022

With social anxiety disorder, an individual experiences marked symptoms of anxiety and distress in one or more specific social circumstances. Some social situations are typically avoided (eg, giving a presentation to peers or eating in public) as the individual fears that they will be perceived in a negative way by others.

The final two disorders in this grouping are separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism. These disorders were originally placed in the childhood disorders chapter of the ICD-10. When an adult develops separation anxiety, it is usually related to an ‘attachment figure’, such as a partner, spouse or child. The individual can experience marked distress when separated, with recurrent nightmares and a refusal to sleep away from the attachment figure. The symptoms must be present for at least several months before a diagnosis can be made. Selective mutism more commonly occurs in children, and typically presents with selectivity in speech in certain social situations such as school. Symptoms must be present for at least one month before a diagnosis can be considered.

For the diagnosis of an anxiety and fearrelated disorder, the symptoms cannot be a direct result of drugs or medications which have effects on the central nervous system. The symptoms must be severe enough to cause significant distress, along with functional impairment in the individual’s life. Depression, alcohol misuse, and drug abuse are common comorbid conditions seen with anxiety disorders which, if left untreated, can aggravate the course and worsen the prognosis.

Treatment

The overall goal in treating anxiety disorders is symptomatic relief, functional improvement and a reduced risk of relapse. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published clear guidance using a ‘stepped care’ approach. The earlier steps predominantly focus on psychological interventions, with individual self-help, psycho-education groups, and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as recognised first-line treatments. Individuals with marked functional impairment, or those who don’t respond to psychological

approaches, will ultimately require pharmacological intervention.

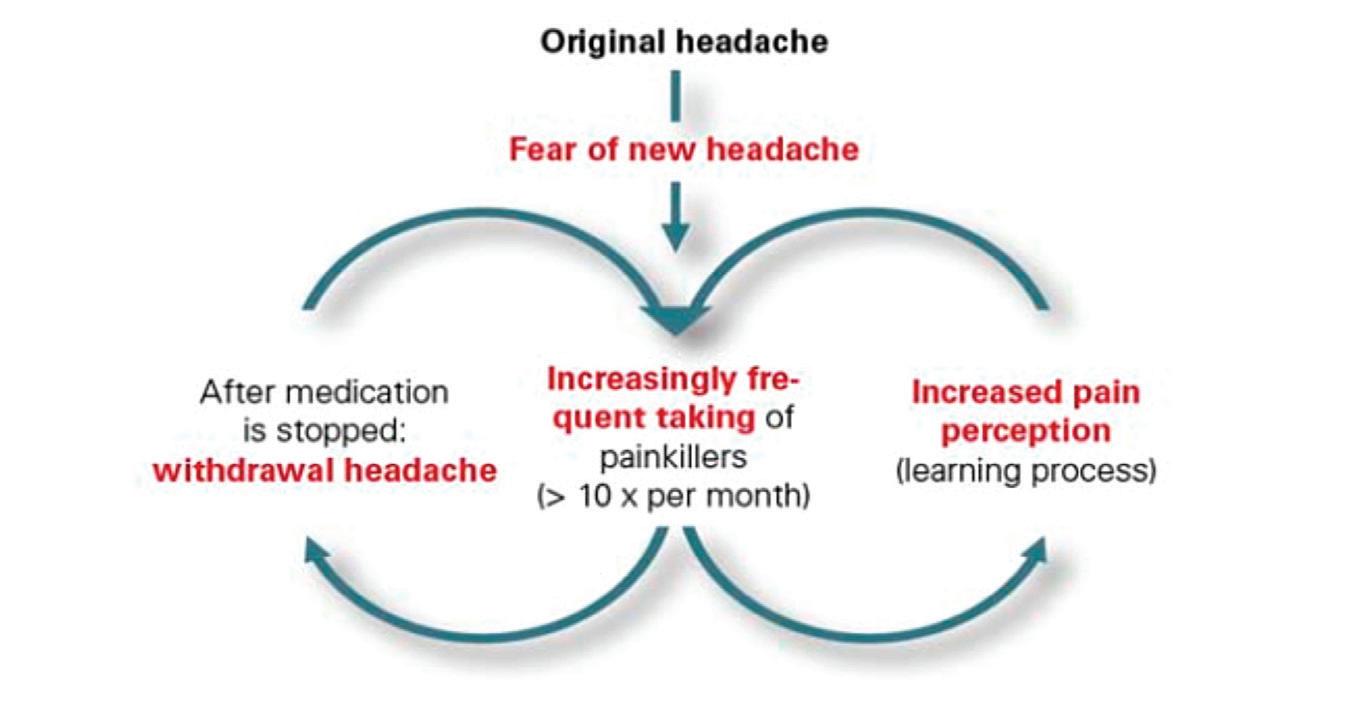

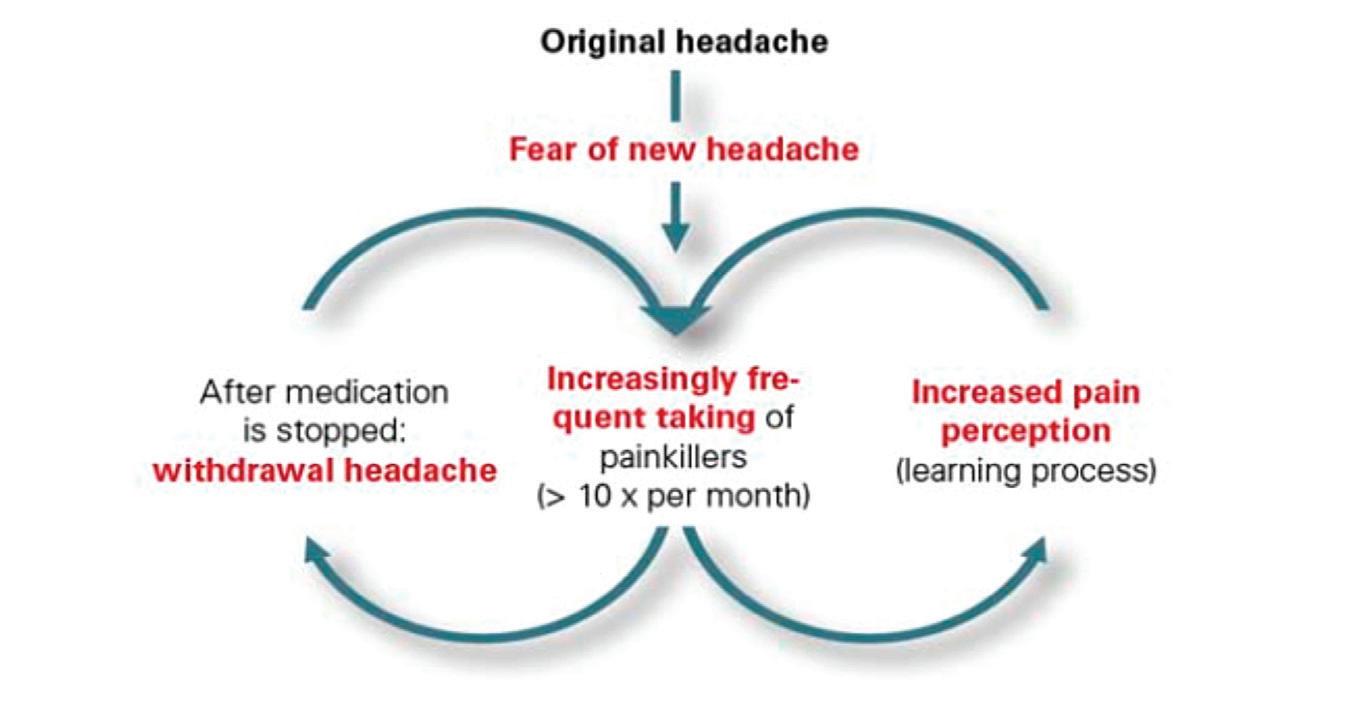

In GAD, the NICE guidance advises sertraline first as it is most cost-effective. If this is ineffective or not tolerated, another SSRI, or an SNRI such as venlafaxine, should be offered. Similarly, for panic disorder, social phobia and agoraphobia, SSRIs should be used as first-line options. Benzodiazepines should not be offered except on a short-term basis during periods of crisis, the exception being panic disorder where they should not be used at all. Pregabalin is listed as a later option in the Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines for treatment of GAD and social phobia; however, it should be used with caution given emerging evidence of its potential for addiction. It is best avoided if there is a history of drug misuse in the patient’s past.