Abstract

Most cross-cultural studies on management control have compared Anglo-Saxon firms to Asian firms, leaving us with limited understanding of potential variations between developed Western societies. This study addresses differences and similarities in a wide variety of management control practices in Anglo-Saxon (Australia, English Canada), Germanic (Austria, non-Walloon Belgium, Germany) and Nordic firms (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden). Unique data is collected through structured interviews from 584 strategic business units (SBUs). We find that management control structures in Anglo-Saxon SBUs, relative to those from Germanic and Nordic regions, are more decentralized and participative and place greater emphasis on performance-based pay. Comparing Germanic SBUs to Nordic ones, we find Germanic SBUs to rely more on individual behaviour in performance evaluation, whereas Nordic SBUs rely more on quantitative measures and value alignment in employee selection. We also observe numerous similarities in MC practices between the three cultural regions. The implications of these findings for theory development are outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Is it a small world of management control (MC) practices? Some scholars have suggested tendencies for a convergence of practices due to, for instance, globalization of markets and transnational regulation (Granlund & Lukka, 1998). Other scholars point to variations in institutional forces and cultural factors that are likely to lead to greater divergence in practices (Bhimani, 1999; Harrison & McKinnon, 1999, 2007). From a managerial perspective, globalization has created a need to understand how, or whether, to adapt MC practices to a local culture. Are some MC practices fit for all cultures, i.e. some form of ‘best practices’, while others need to be tailored to local circumstances to achieve desired outcomes? As Merchant et al. (2011) argue, we are at the early stage in our understanding of which MC practices should be adapted, and how, to suit a particular cultural context.

In this study we seek to understand variation in how MC practices are designed and used between different Western cultural regions. The focus of this study was chosen for two main reasons. First, most prior studies have focused on comparisons between Anglo-Saxon (mostly US and Australia) and Asian firms (see Endenich et al., 2011). To develop a more general theory of the influence of culture on the design and use of MC practices we need to explore how they vary between other cultural regions. In particular, there are significant cultural differences between Western nations (Hofstede, 1980, 2001; House et al., 2004), and these differences are likely to have implications for the design and use of MC practices (see e.g. Jansen et al., 2009). However, apart from five notable studies (Chiang & Birtch, 2012; Newman & Nollen, 1996; Peretz & Fried, 2012; Roth & O’Donnell, 1996; Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004), the empirical evidence as to whether or not MC practices vary between Western cultures and to what extent, is based on data collected in no more than three nations in each study (Ahrens, 1997; Dossi & Patelli, 2008; Jansen et al., 2009; Lubatkin et al., 1998; Pennings, 1993; Van der Stede, 2003).

Second, the range of MC practices examined in cross-cultural analysis is relatively limited, with most studies focusing on incentive systems, budgeting and performance measurement (Chow et al., 2002; Harrison, 1993; Jansen et al., 2009; Merchant et al., 2011; Van der Stede, 2003), and selected administrative controls (Birnberg & Snodgrass, 1988; Chow et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1994; Williams & Seaman, 2001). The MC literature, however, points to a much wider range of practices available to managers to influence the behaviour of subordinates (Bedford & Malmi, 2015; Malmi & Brown, 2008; Merchant & Van der Stede, 2007; Simons, 1995). Currently, there is little understanding about whether or not the design and use of a wider range of MC practices are, or should be, adapted to different cultural contexts.

One general research question guides our inquiry: do MC practices vary in different Western cultural regions? As there is relatively little prior investigation into how MC practices vary between Western regions, we start with this broad research question instead of stating specific hypotheses on known constructs (Locke, 2007). We then assess whether differences in a wide range of MC practices between the studied regions are (or are not) consistent with variations in their cultural characteristics. Hence, the study is exploratory in nature, predominately designed to provide an empirical basis to support the development of a more comprehensive theory to explain cross-cultural variation in MC practices.

In this study, we draw on Malmi and Brown’s (2008) framework of MC as a package.Footnote 1 This framework suggests that MC practices should be understood in a broad sense and encompasses accounting and measurement systems, for instance performance measurement and budgeting, as well as organizational structure, administrative processes and cultural controls. In this vein, we understand MC practices as those ‘systems, rules, practices, values and other activities management put in place in order to direct employee behaviour’ (Malmi & Brown, 2008, p. 290). In this study, we address a large variety of MC practices to provide empirical evidence for subsequent theory development regarding how and why MC practices should (or should not) be adapted to cultural circumstances.

We study MC practices in three cultural regions: Anglo-Saxon (Australia, English Canada), Germanic (Austria, non-Walloon Belgium and Germany) and Nordic (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden). Our choice is motivated by the limited understanding as to how MC practices in the Germanic and Nordic regions vary in relation to the Anglo-Saxon region (Newman & Nollen, 1996). We adopt the definitions of these cultural regions from the Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness Research (GLOBE). The GLOBE study builds upon Hofstede (1980), but also draws upon a substantial amount of theoretical and empirical literature subsequent to Hofstede’s work. Furthermore, the GLOBE study focuses on supra-national regions rather than differences between nation states, which cannot necessarily be equated with cultures (Baskerville, 2003; Beugelsdijk et al., 2017). The GLOBE study clusters societies based on religion, language, geography and ethnicity, and work-related values and attitudes (Gupta & Hanges, 2004). By using cultural regions, we are also able to control for country-level institutional and other differences. Hence, we draw on the most comprehensive research available to categorize societies into cultural regions that have similar cultural implications for the design and use of a firm’s MC practices.

Data for this study are from a survey conducted through structured interviews from 584 strategic business units (SBUs) in these countries. The sample size, as well as the method of data collection, enhances the reliability of our findings. Although the data comes from SBUs from different industries, the sampling was stratified to ensure similar enough distribution of SBUs from different industries and of different sizes from each country and region. We also control for a wide range of contextual factors, including dimensions of the environment and firm strategy, as well as a number of other potential explanatory factors, to reveal variations in MC practices consistent with differences in the cultural characteristics of each region.

Our findings reveal that Anglo-Saxon SBUs delegate decision rights, use matrix organization structures, boundary systems and pre-action reviews, involve subordinates in strategic planning activities, rely on relative performance measures, emphasize performance-based pay, use both predetermined quantitative targets and subjectivity in determining subordinate compensation, use non-financial rewards, and emphasize socialization processes to reinforce SBU values and beliefs more than their counterparts in Germanic and Nordic regions do. When assessing differences between Germanic and Nordic MC practices, we find Germanic SBUs to delegate strategic decisions, use pre-action reviews, use individual behaviour for evaluating subordinate performance, use non-financial rewards and connect leadership performance to rewards and promotion, more than their Nordic counterparts do. Nordic SBUs rely on matrix structures, use a larger number of measures, rely more on financial and relative performance measures to evaluate subordinate performance, rely more on financial rewards, emphasize alignment with organizational values in selection decisions and require rotation in promotions more compared to Germanic SBUs. Additionally, despite cultural differences, the participation of subordinates in action planning and the diagnostic use of budgets and performance measurement systems, among other practices, appear similar across regions.

The primary contribution of this study is to provide empirical evidence for how a wide range of MC practices vary between Western cultural regions. Specifically, we reveal the differences and similarities between Anglo-Saxon, Nordic and Germanic cultural regions, of which comparisons between the latter two have been the subject of little examination in prior MC research (Newman & Nollen, 1996; Peretz & Fried, 2012). While it is beyond the scope of this study to develop a more comprehensive theory of how cultural traits influence the design and use of MC practices, we discuss the potential implications of our findings for future theory-building efforts.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. The next section reviews prior literature on cultural regions as well as on how and why culture is expected to relate to MC practices, which MC practices have been studied in which settings, and what has been found. The third section describes the research method. Results are presented in section four. The final section discusses the results, presents the contributions of the study, the limitations, and provides suggestions for further research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Cultural regions

Contingency-based research assumes that because different countries possess particular cultural characteristics, individuals from within these cultures will react differently to the same MC practice (Chenhall, 2003). Prior cross-cultural MC research has relied predominantly on Hofstede’s typology. In this study, we draw on two categorizations of the GLOBE study (House et al., 2004)Footnote 2: their extended nine cultural dimensions and their concept of cultural regions.

Scholars of the GLOBE study define culture as ‘shared motives, values, beliefs, identities, and interpretations or meanings of significant events that result from common experiences of members of collectives that are transmitted across generations’ (House & Javidan, 2004, p. 15). Culture is operationalized with several cultural dimensions, which were selected based on prior literature. Building on and extending Hofstede’s (1980) and Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s (1961) work on culture, GLOBE researchers identified nine cultural dimensions including organizational and societal practices (‘As Is’) and values (‘Should Be’): assertiveness, future orientation, humane orientation, institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, performance orientation, power distance, uncertainty avoidance and gender egalitarianism. The definitions of these cultural dimensions are provided in Table 1, including differences between Hofstede and GLOBE.

While both Hofstede (2001) and GLOBE (House et al., 2004) study culture at the country or national level, GLOBE scholars also study the supra-national level by constructing ten regional clusters (Gupta & Hanges, 2004).Footnote 3 Research indicates that cultural differences may be more driven by the supra-national level than by the national level (Beugelsdijk et al., 2017). The GLOBE cultural region scores and averages and explanations for each construct are displayed in Table 2.Footnote 4 In addition to the cultural regions’ mean values of the GLOBE study, it contains the mean values of the cultural regions of our sample and, in the last row, the resulting differences between the regions. In the next section, we will use these differences in cultural dimensions to try to elucidate the variation in MC practices across the three regions. It is important to note that Table 2 shows cultural dimension scores in relation to actual practices. The GLOBE study of national culture asked respondents about both societal practices, referring to ‘things as they are’, as well as societal values, which relates to ‘as things should be’. We base our comparative analysis on responses to societal practices as ‘shared values are enacted in behaviors, policies, and practices’ (House & Javidan, 2004, p. 16). Furthermore , House and Javidan (2004) argue that it is societal practices that affect leadership behaviours and organizational practices, because managers must respond to the way things actually are in practice.

2.2 The effects of national culture on the design of MC practices

Below, we briefly discuss the cross-cultural research that has been conducted on MC practices. Table 3 provides a summary of prior work. Definitions of the examined MC practices in this study are provided in Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 and “Appendix A”.

Uncertainty avoidance is the degree to which members of a society cope with ambiguous situations where outcomes are unsure (House & Javidan, 2004). According to the GLOBE study (Sully de Luque & Javidan, 2004), in societies that score high on uncertainty avoidance (e.g. our Nordic and Germanic regions), organizations prefer to rely on formalization and standardized procedures and rules. Empirical accounting research has found some support for this (Chow et al., 1994, 1996), with Newman and Nollen (1996) even showing well-defined rules and directions in high uncertainty avoidance settings having positive performance consequences, but contradictory results are also reported. In particular, Birnberg and Snodgrass (1988) found that, despite their high uncertainty avoidance, Japanese firms used fewer bureaucratic procedures than US firms. They ascribe this contradictory finding to Japan’s homogenous and cooperative culture, which makes rules and enforcements less necessary.

Hoffman (2007) investigated whether strategic planning enhances firm performance in Anglo-Saxon, Nordic and Germanic cultures and found that the strength of the planning-performance relationship was largest within the Nordic culture. This was attributed to uncertainty avoidance and power distance. Uncertainty avoidance has been related to frequent formal performance appraisal (Chiang & Birtch, 2010) and is argued to be negatively related to the proportion of variable compensation incorporated into incentive contracts (Gomez-Meija & Welbourne, 1991; Segalla et al., 2006; Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004). However, conflicting evidence also exists (Chiang & Birtch, 2006). Uncertainty avoidance has also been suggested to relate to employee selection: firms from high uncertainty avoidance cultures fill top positions in foreign subsidiaries with persons from their own culture (Brock et al., 2008; Chang & Taylor, 1999).

Power distance is the extent to which members of a society agree that power should be stratified and concentrated at higher levels of an institution (House & Javidan, 2004). Prior research suggests that the extent of decentralization, or centralization, is associated with variations in power distance (Harrison et al., 1994). In particular, according to Hofstede (1980), it is more likely to find a higher degree of authority centralized at the top levels of firms in high power distance nations. Additionally, GLOBE research (House & Javidan, 2004) posits that in low power distance societies, forces towards centralization tend to be weaker than in high power distance societies. Empirical accounting research has addressed centralization and decentralization in Anglo-Saxon and East-Asian firms and found support for these predictions (Chow et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1994; Williams & Seaman, 2001). Similarly, Meyer and Hammerschmid (2010) found the extent to which human resource management decision authority is decentralized in Europe (i.e. the 27 EU member states) to be in line with these predictions.

Power distance has been used to explain attitudes towards budget participation (Harrison, 1992; Li & Tang, 2009; Otley, 2016). In a low power distance society, subordinate reactions to participation are likely to be favourable, whereas in a high power distance society, subordinates are likely to prefer less participation (Elenkov, 1998; O’Connor, 1995). Empirical accounting research has addressed this in various cultures and found support for the idea that power distance plays a role in the extent of participation, how participation is perceived and also how participation influences organizational outcomes (Brewer, 1998; Lau & Caby, 2010; Lau & Eggleton, 2004; Lubatkin, et al., 1998; Newman & Nollen, 1996; O’Connor, 1995; Tsui, 2001).

It has been argued that individuals in a high power distance society prefer clearly specified performance criteria such as financial performance measures and adherence to them in evaluation (Chiang & Birtch, 2006). In contrast, low reliance on financial performance measures generates more positive outcomes in low power distance/high individualism societies because it implies greater incorporation of person- and situation-specific factors into performance evaluation (cf. Chiang & Birtch, 2005, 2007). Power distance is also argued to be associated with target difficulty: individuals in high power distance cultures are likely to be satisfied with high-stretch performance standards. Empirical accounting research provides support for these associations (Chow et al., 2001, 2002; Harrison, 1993).

Power distance has been found to be positively related to the proportion of variable compensation incorporated into incentive contracts (Chiang & Birtch, 2006, 2007; Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004). High power distance and masculine (high assertiveness) cultures seem to link financial rewards to high performance (Fischer, 2004; Giacobbe-Miller et al., 1998; Gooderham et al., 2006), whereas the link between performance on non-financial measures and rewards appeared to be stronger in feminine (low assertiveness) and low power distance cultures (Chiang & Birtch, 2006, 2012; Newman & Nollen, 1996). Multinationals in societies with high power distance tend to staff vital managerial positions in their foreign subsidiaries with individuals from their own culture (Brock et al., 2008).

Individualism / collectivism describes the tendency of people to see themselves as individuals as opposed to members of a group. GLOBE research refers to institutional collectivism, reflecting the degree to which societal practices encourage and reward collective over individual action (House & Javidan, 2004) and in-group collectivism, which is the degree to which individuals take pride in being a member of a collective, for instance organizations, teams, families or clans (House & Javidan, 2004).

Like with power distance, prior research suggests that the extent of decentralization, or centralization, is associated with variations in individualism (Harrison et al., 1994). Similarly, variation in the use of rules and standardized procedures has been associated with individualism. Low individualism implies that one accepts having less control over own work-related actions. In line with this, Chow et al. (1999) show that Taiwanese managers employed by a local Taiwanese-owned firm (lower in individualism) used more written policies, rules, standardized procedures and manuals than those employed by a Japanese-owned firm (higher on individualism).

Individualism has been used to explain attitudes towards budget participation (Harrison, 1992; Li & Tang, 2009; Otley, 2016), but the arguments, and findings, are not conclusive. Some authors claim that participation is culturally appropriate in an individualist society because it provides a mechanism to internalize goals and standards (Milani, 1975). However, most authors have argued that participation works best in collectivist societies as group decisions are believed to be superior to those made by an individual (Harrison, 1992). The effects of budgetary participation have been shown to be independent of culture, a result attributed to the offsetting effects of the low power distance and high individualism of many Anglo-Saxon nations and the offsetting effects of the high power distance and low individualism of many Asian nations (Erez & Earley, 1987; Lau & Tan, 1998; Lau et al., 1995, 1997).

Due to their comparability, financial performance measures are preferred in collectivist societies, in which people are concerned with comparisons with others (Hui, 1988). In contrast, low reliance on financial performance measures generates more positive outcomes in low power distance/high individualism societies because it implies greater incorporation of person- and situation-specific factors into performance evaluation (Chiang & Birtch, 2005, 2007). Individualism is also argued to be associated with target difficulty: individuals in low individualism cultures are likely to be satisfied with high-stretch performance standards. Empirical accounting research provides support for these associations (Chow et al., 2001, 2002; Harrison, 1993). Individualism has also been related to other aspects of performance evaluation. In individualist societies, where organizational loyalty tends to be relatively lower, people favour short-term evaluations and immediate rewards for personal efforts and achievements (Ueno & Sekaran, 1992). Frequent formal appraisal has also been related to low (in-group) collectiveness (Chiang & Birtch, 2010). In addition, it has been suggested that the degree of collectiveness has an impact on how managers appraise their employees’ performance in that it influences managers’ perception of their employees’ motivation as well as how they weigh these perceptions when appraising employee performance (DeVoe & Iyengar, 2004).

In individualist societies, performance-based reward systems are utilized more (Bae et al., 1998; Newman & Nollen, 1996; Schuler & Rogovsky, 1998) and stronger links can be expected between individual compensation and personal success (Awasthi et al., 2001; Daley et al., 1985; Pennings, 1993; Schuler & Rogovsky, 1998). Moreover, firms in individualist societies are likely to make more use of long-term incentives because otherwise managers will emphasize their own short-term gains at the expense of what is best for their firm’s long-term success (Merchant et al., 1995). Individualism has been found to be positively related to the proportion of variable compensation incorporated into incentive contracts (Chiang & Birtch, 2006, 2007; Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004).

Hofstede refers to masculinity to represent a cultural preference for achievement, assertiveness and material success, and femininity to describe a greater importance placed on maintaining relationships, caring for members and a high quality of life. GLOBE research refers to assertiveness and humane orientation. Individuals from societies scoring high on assertiveness tend to be confident, tough, confrontational and even aggressive in social relationships (House & Javidan, 2004). In high humane orientation societies, ‘others are important (i.e. family, friends, community, strangers)’ and ‘values of altruism, benevolence, kindness, love and generosity have high priority’ (Kabasakal & Bodur, 2004, p. 570).

Masculine (high assertiveness) cultures seem to link financial rewards to high performance (Fischer, 2004; Giacobbe-Miller et al., 1998; Gooderham et al., 2006), whereas the link between performance on non-financial measures and rewards appeared to be stronger in feminine (high humane orientation) and low power distance cultures (Chiang & Birtch, 2006, 2012; Newman & Nollen, 1996). Indeed, in masculine societies, the trend has been to make jobs more interesting by providing workers with greater autonomy and greater accountability (Jansen et al., 2009). Jansen et al.’s (2009) study of incentive compensation practices in the automobile retail sector in the US and the Netherlands (a feminine, low assertiveness country in which people are future-oriented) demonstrates that the national setting does seem to matter in incentive system design. Compared to the US firms, the Dutch firms were much less likely to provide their managers with incentive compensation in any form. Moreover, Dutch firms based their bonus awards more on non-financial performance measures and used more performance bounds in their performance/reward functions. Merchant et al. (2011) extended the results to Chinese automobile retailers and found that differences in masculinity (high assertiveness) could explain differences in the use of incentive compensation in firms in the three countries.

Managers in societies with high values of assertiveness tend to exert robust control in their organization and think of people as acting opportunistically (Den Hartog, 2004). When the parent company of a multinational corporation (MNC) is based in such a society, one way to exert tighter control is to staff the subsidiary with managers from the home country. Indeed, Brock et al. (2008) find that MNCs based in highly assertive countries choose this form of cultural control.

Scholars of GLOBE describe gender egalitarian societies as those ‘that seek to minimize differences between the roles of females and males in homes, organizations, and communities’ (Emrich et al., 2004, p. 347). Because research on the influence of gender on MC practices is still limited (Parker, 2008), we could only identify one study that considered, but not hypothesized, gender equality across cultures. However, the authors could not find gender egalitarianism significantly influencing the staffing control of MNCs (Brock et al., 2008). Societies that score high on gender egalitarianism manifest higher levels of gender equality and, therefore, we find higher economic activities of women and more women in management positions (Emrich et al., 2004). Hence, gender egalitarianism could lead female managers to use controls interactively to a more considerable extent than their male counterparts (Bobe & Kober, 2020). Moreover, they could use more performance measures than male managers because they use more non-financial performance measures (Bobe & Kober, 2020).

Societies scoring high on future orientation encourage and reward behaviour such as planning or delaying gratification (Ashkanasy et al., 2004; Kluckhohn & Strodtbeck, 1961). These societies tend to have longer time horizons for decision making (Hofstede, 2001). Societies with a high performance orientation encourage and reward their members if they succeed in doing an activity (House & Javidan, 2004). Only two prior studies have linked these cultural dimensions to MC practices. Myloni et al. (2004) use four of the GLOBE cultural dimensions to compare performance evaluation practices between Greek firms and MNC subsidiaries from Europe, US and Japan. Performance evaluation is suggested to be more subjective (e.g. higher degree of favouritism and less use of written reports) in Greek firms compared to MNC subsidiaries, due to low performance orientation and future orientation and high in-group collectivism and power distance. The study by Tsui (2001) suggests that the long-term oriented, high collectivism and large power distance culture explains why high levels of budgetary participation in the presence of available management accounting information would not result in high managerial performance for Chinese managers.

2.3 Summary

Taken together, cross-cultural research on MC practices has provided informative, albeit somewhat mixed, results on how MC practices are tailored to suit local cultural circumstances, but these studies have predominantly focused on comparisons between a variety of Asian nations and the US or Australia (Harrison & McKinnon, 1999). Power distance and individualism have been the aspects of culture authors have most often drawn on, but observed differences are also attributed to uncertainty avoidance and masculinity/assertiveness. However, it is not always clear which cultural dimensions might best explain the observed differences. As Van der Stede (2003, p. 268) notes, one reason for the mixed support for contingency-type national culture effects on the design and use of MC practices arises from the fact that the cultural dimensions operate simultaneously and may create reinforcing or opposing effects on an individual’s preferences for MC practices. Further, it is not obvious we should expect to see linear relations between cultural traits and the design of MC practices. It may well be that once a cultural trait(s) is (are) predominant enough, certain MC practices are relied upon (or not), suggesting, for instance, linked relations.

There are cultural regions different from the Anglo-Saxon and Asian regions, including the Germanic and Nordic regions. According to the GLOBE study, these regions have distinctive cultural characteristics that may affect how companies in the respective regions use their MC practices, as for example the study by Jansen et al. (2009) suggests. Moreover, there are MC practices, such as planning and cultural controls, that have yet to be studied extensively, or at all, in cross-cultural research. Even within MC practices that have been studied more extensively, there are several attributes of those practices that are still to be explored. For the reasons outlined, we do not have enough ground to develop specific hypotheses on differences between MC practices in these cultural regions. Our study is explorative in nature and we will compare our findings to those presented in the prior literature in the discussion section.

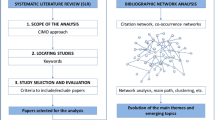

3 Method

3.1 Data collection and sample

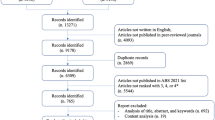

This study uses data from a comprehensive surveyFootnote 5 conducted in eleven countries, of which nine are included in the analysis.Footnote 6 The same survey instrument was used in all countries (Schaffer & Riordan, 2003). The survey instrument was originally developed in English and then translated into the local language. The survey was subsequently back-translated by an independent researcher (Harkness, 2003) to ensure consistency in meaning (Van De Vijver & Leung, 1997). The survey instrument underwent extensive pre-testing in each country with academics in the MC discipline, as well as practitioners that are representative of the target population. Sample information for each country is detailed in Table 4.

The survey population consists of private for-profit companies that have more than 250 employees. This minimum criterion was established to ensure that the MC variables of interest would be observed. Firms were selected for inclusion through a stratified sampling approach (Cochran, 1977). Samples were stratified by industry (manufacturing, service and wholesale) and size (medium, defined as firms with 250 to 1000 employees; and large, defined as firms with 1000 or more employees). For European countries, the sample was drawn from the ORBIS database, Dun and Bradstreet was used for the Australian sample and the Scott’s National database for the Canadian sample.

The unit of analysis is the SBU, which is defined as a relatively independent entity that has a unique market context (in relation to other SBUs of the firm) and competitive strategy. Studying SBUs should reveal a more homogeneous sample than examining MC practices at the company level (Kruis et al., 2016), as each business unit is likely to face unique competitive and contextual situations when compared with other business units of the firm. In some cases, firms operated as single independent businesses. Following prior literature, SBUs and independent firms were considered to be empirically comparable (e.g. Chenhall & Langfield-Smith, 1998; Henri, 2006). In these cases, questions referring to the SBU-group headquarters relationship were ignored. Target respondents are CEOs and managing directors of SBUs. If they were unable to be interviewed, we asked them to nominate another member of the top management team who had detailed knowledge of the SBU’s MC practices and operating environment. Almost all interviews took place with a single interviewee. Respondent titles and average interview durations by country are displayed in Table 5.

Data collection took place from November 2009 to March 2013. Within individual countries, the data collection period lasted between 8 and 17 months, with a mean of 14 months. Due to the detailed and comprehensive nature of the survey instrument, data were collected through structured interviews. This increases the reliability of survey responses as any ambiguities are able to be clarified with the respondent. Furthermore, respondents were asked to briefly discuss the reasoning behind scores to each item, allowing the interviewer to assess any potential misinterpretation of the questions or response categories. Endenich et al. (2011) warn that such ambiguities may be particularly important in cross-country studies due to culture-specific perceptions of identical phenomena. Minimizing ambiguity and ensuring respondents answered each question with explicit reasoning should, therefore, provide a more reliable and valid set of data, than otherwise would have been the case had data been obtained from the more typical mail- or internet-based approaches.

In total 2199 firms were invited (via telephone or email) to participate in the study, with 694 firms agreeing to participate. We eliminated SBUs with shared headquarters and those with headquarters in a different cultural region. We also removed nine cases where there were significant missing data.Footnote 7 Omitting these cases left a usable sample of 584 responses. Structured interviews were conducted face-to-face (70%) or by telephone (30%). Where possible, interviews were audio-recorded. Most of the interviews were conducted by one or more of the researchers involved in the project (77%), although some were conducted by research students who were trained to collect the data (23%). To ensure consistency and reliability of collected data, interviewers were provided a comprehensive lexicon outlining concrete definitions and illustrations of the MC practices and dimensions being assessed by each question.Footnote 8

Participants were assured anonymity and were explicitly informed that there are no right or wrong answers. At the start of the interview, participants were informed in general terms about the purpose and structure of the interview. Interviewers asked the participants explicitly to answer questions from their perspective (SBU top management) and not from a headquarter perspective. Questions were always asked in the same sequence to create an identical flow of questions/answers across all interviews. Coding procedures were applied uniformly, and a check of the data for consistency and missing values was finally conducted at research group level and at the local level in each country.

3.2 Variable measurement

We used several constructs for each MC practice category outlined in Malmi and Brown (2008). Six constructs were used for administrative controls, two for strategic planning, three for action planning, nine for performance measurement and evaluation, seven for rewards and compensation, and seven for cultural controls, resulting in 34 constructs used as dependent variables. In addition to the region variable, 13 variables were used to control for other contextual determinants. This includes aspects of the SBU’s external environment and strategy, and firm characteristics such as size and ownership structure. To control for potential biases from the collection method we also included interviewer (researcher/student) and interview type dummies (face-to-face/telephone). A complete outline of control variables and definitions is provided in “Appendix A”.

We draw on existing construct measures where possible, and follow current recommendations to assess the reliability and validity of construct measures (Bedford & Speklé, 2018). “Appendix B” lists items, anchors and Cronbach alpha for reflective constructs (between 0.60 and 0.88). Confirmatory factor analyses for the reflective constructs show factor loadings > 0.54 for all items (see “Appendix B”). For formative constructs, we checked item weights on the first principal component (Petter et al., 2007). Item weights on all formative constructs are positive and have weights above the recommended minimum of 0.30 (Hair et al., 2017; see “Appendix B”). Variance inflation factors (VIF) are calculated to assess multicollinearity. The maximum VIF of 2.63 is below the general threshold of 5 (Hair et al., 2017).

4 Results

We use ANCOVA and Tukey contrast analyses to assess differences in MC practices between the three cultural regions. The results reported in Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 show significant regional differences at the 0.05 or lower level. All p-values were adjusted using the false discovery rate method (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) to limit the risk of identifying false positives. Descriptive statistics of the MC practices and contextual variables are provided in “Appendix C”.

The ANCOVA model for each CONTROL_PRACTICE is:

For REGION, Anglo serves as the base against which Germanic and Nordic regions are compared; for OWNERSHIP, the dummy variables should pick up family, government, institutional and venture capitalists controlling for ownership effects; and for INDUSTRY, the base ‘manufacturing’ is compared to ‘service’ and ‘wholesale’.

We also estimated the models with single-digit NACE code industry effects, resulting in only minimal differences in the significance levels of mean differences. Estimating the corresponding OLS models yielded identical results.

4.1 Administrative controls

We find a clear cultural difference in the delegation of decision rights as shown in Table 6: top management in Anglo-Saxon SBUs delegate strategic, business and operational decisions more compared to other cultural regions (p < 0.001). Germanic leaders delegate strategic decisions more than Nordic leaders do. We also asked respondents to assess the extent to which subordinates have multiple reporting lines (some form of matrix organization). Subordinates in Anglo-Saxon SBUs have a higher level of multiple reporting lines compared to Nordic SBUs, and Nordic SBUs compared to Germanic SBUs (p < 0.001). Hence, although subordinates in Anglo-Saxon SBUs have more power to decide on various issues than their counterparts in other cultural regions do, they are also monitored by a larger number of managers.

We asked the respondents to assess the extent to which they rely on various types of rules and procedures in guiding and directing subordinate behaviour. Anglo-Saxon SBUs use boundary systems to a higher extent than SBUs in the other cultural regions (p < 0.001). Anglo-Saxon SBUs rely on pre-action reviews more than Germanic SBUs and Germanic SBUs more than their Nordic counterparts (p < 0.01).

Our findings are not in line with GLOBE research (House & Javidan, 2004) and prior accounting literature (Chow et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 1994; Williams & Seaman, 2001) with regards to variation in the allocation of decision rights. In our sample, the Anglo-Saxon region scores in-between the Nordic and Germanic regions in power distance, but Anglo-Saxon SBUs allocate decision rights more extensively than SBUs in other regions. The lower degree of decentralization in Nordic and Germanic regions is consistent with the higher uncertainty avoidance in these regions as subordinates in high uncertainty cultures prefer clear guidance and prescribed actions (Williams & van Triest, 2009). Our finding that Anglo-Saxon SBUs rely on more complex communication and accountability structures (i.e. matrix organizations) than Germanic and Nordic SBUs, and Nordic SBUs more than Germanic SBUs, is consistent with differences in humane orientation. The higher the humane orientation, the more likely managers have the skills to develop interpersonal relationships and manage the conflicts inherent in matrix organizations. Moreover, the more extensive use of matrix organizations can also result from a greater delegation of decision rights, allowing multiple managers to monitor subordinate decisions. This would imply that matrix structures are explained by differences in uncertainty avoidance.

In contrast, although the GLOBE classification (Sully de Luque & Javidan, 2004) and some prior accounting research (Chow et al., 1994, 1996) suggest that in societies that score high on uncertainty avoidance (such as our Germanic and Nordic regions) organizations prefer to rely on formalization and standardized procedures and rules, our results suggest these are relied on equally or even more in Anglo-Saxon SBUs. However, this result can be explained by the different focus of this study compared to prior research. Prior literature has focused on the degree of formalization more generally and the use of standardized rules and procedures that specify how activities must be conducted. In contrast, this study examines the use of pre-action reviews and boundary systems, which specify behaviours to be avoided rather than how they should be done. The more extensive delegation of decision rights by Anglo-Saxon SBUs may explain why boundary systems, which act to limit excessive risk tasking by subordinates, are emphasized more in Anglo-Saxon SBUs than in Germanic and Nordic SBUs. For the differences in the use of pre-action reviews, GLOBE dimensions do not provide a culture-related explanation.

4.2 Strategic and action planning

Table 7 reveals that participation of subordinates in strategic planning is less common in Nordic and Germanic SBUs compared to Anglo-Saxon SBUs (p < 0.001). We do not find differences in the autonomy subordinates have in developing action plans between the studied cultures. We also asked respondents how short-term targets are set for both ends and means. In the majority of the SBUs, top management set targets for ends, i.e. what needs to be achieved, either as a top-down process or based on negotiations, and we do not find cultural differences in terms of autonomy granted to subordinates in setting targets for ends. Subordinates have, on average, more impact on targets set for means (i.e. how ends are to be achieved), but we find no cultural differences in this regard either.

In prior accounting literature, participation is related to power distance and individualism, but it is discussed mainly in relation to budgeting rather than strategic planning. The finding that subordinates in the Anglo-Saxon region participate in strategic planning activities more than their counterparts in the Germanic and Nordic regions cannot be explained by differences in power distance or institutional and in-group collectiveness (see Table 2). The low uncertainty avoidance and high humane orientation in the Anglo-Saxon region is consistent with the more prevalent participation in strategic planning. Managers in this region get along with the uncertainty of strategic planning and do not expect their superiors to give them precise instructions on how to act. Through participation, subordinates feel that they are taken seriously, welcome the investment in interpersonal relationships, and appreciate the trust their superiors place in them. Although the studied cultural regions differ in terms of institutional collectivism, our results indicate no significant variations in participation in action planning processes.

4.3 Performance measurement and evaluation

In assessing whether budgets and performance measures are used diagnostically, our results indicate no differences between cultural regions (see Table 8). However, Anglo-Saxon SBUs rely on interactive use of budgets (p < 0.01) and performance measurement systems (p < 0.01) more compared to Nordic SBUs.

Simons (2005) has argued that the more measures there are to evaluate subordinates’ performance, the less a subordinate can use her discretion in an attempt to achieve good results and vice versa. Our results indicate that Nordic SBUs use a higher number of measures that subordinates are accountable for than Germanic SBUs (p < 0.05).Footnote 9 Both Anglo-Saxon and Germanic SBUs include more individual behaviours, such as leadership achievements and individual effort, in performance evaluation than Nordic SBUs (p < 0.01). In evaluating subordinate performance, SBUs in all cultural regions put similar emphasis on non-financial measures, while financial measures are used more in the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic regions compared to the Germanic region. Compared to Anglo-Saxon SBUs, the use of relative performance evaluation is less common in Germanic and Nordic SBUs, and less common in Germanic compared to Nordic SBUs (p < 0.001).

It is not obvious which cultural dimensions can be associated with interactive use of budgets and performance measurement systems. High institutional collectivism could be one, as it refers to the degree to which organizational and societal institutional practices encourage and reward collective action, but it does not get support from our findings. Another is uncertainty avoidance. Individuals in cultures with low uncertainty avoidance perceive uncertain situations as an opportunity, whereas planning and structure are more preferable in higher uncertainty avoidance cultures. Interactive control encourages dialogue between superiors and subordinates in order to find ways to take advantage of strategic uncertainties (Simons, 1995). Therefore, cultures high in uncertainty avoidance are more likely to favour using budgets and performance measurement systems interactively. Gender egalitarianism, if it leads to higher proportions of women in management, should lead to increased interactive use of controls because women tend to prefer the transformational leadership style (Bobe & Kober, 2020). Anglo-Saxon SBUs using budgets and performance measurement systems more interactively than Nordic SBUs is not in line with what GLOBE dimensions with respect to these regions would suggest.

Prior accounting literature (Harrison, 1993) indicates that power distance and individualism are related to the extent to which financial performance measures are relied upon in performance evaluation. It is argued that low reliance on financial performance measures generates more positive outcomes in low power distance/high individualism societies because it implies greater incorporation of person- and situation-specific factors into performance evaluation (cf. Chiang & Birtch, 2005, 2007). In our study, Nordic and Anglo-Saxon SBUs rely most on financial performance measures, despite their lower power distance than the Germanic region. Although our findings are in conflict with those of Harrison (1993), they are consistent with the effect of the lower power distance of the Nordic and Anglo-Saxon regions being overridden by their higher institutional collectivism.

In addition, we find that Anglo-Saxon and Germanic SBUs incorporate more individual behaviours, such as leadership achievements and individual effort, in performance evaluation than Nordic SBUs. This is again consistent with differences in institutional collectivism, although there are some differences in this cultural dimension between the Anglo-Saxon and Germanic regions as well (see Table 2).Footnote 10 Nordic SBUs, in contrast, hold their subordinates accountable for a larger number of performance measures than Germanic SBUs do. This is partly in line with our data, as Nordic countries practice higher gender egalitarianism than Germanic countries and, accordingly, women tend to use more information for performance evaluation than men (Bobe & Kober, 2020). However, we find no differences between the Anglo-Saxon and European regions.

4.4 Rewards and compensation

Results reported in Table 9 show that there are differences in how reward and compensation systems are used in the different cultural regions. First, emphasis on performance-based pay is higher in Anglo-Saxon SBUs compared to Nordic and Germanic SBUs (p < 0.001). For the proportion of incentive payout of total annual compensation to subordinates, we find no significant differences between regions.Footnote 11 Second, Nordic and Anglo-Saxon SBUs rely more heavily on financial rewards than Germanic SBUs (p < 0.01). Third, Anglo-Saxon SBUs also use non-financial rewards more than SBUs in the two other cultural regions, and Germanic SBUs use non-financial rewards more compared to Nordic SBUs (p < 0.001). Fourth, Nordic and Germanic SBUs emphasize more non-financial measures in determining subordinate compensation than Anglo-Saxon SBUs (p < 0.01). Fifth, Anglo-Saxon SBUs use both subjectivity (p < 0.001) as well as predetermined quantitative targets (p < 0.05) in determining subordinate compensation more than Germanic and Nordic SBUs.

SBUs in all regions use incentive systems, but place different emphases on different aspects of them. Prior literature has attributed the more extensive use of incentive systems to individualism. We find a stronger emphasis on performance-based pay by Anglo-Saxon SBUs. However, scales related to individualism in GLOBE research, i.e. institutional collectivism and in-group collectivism, cannot explain this finding as the Anglo-Saxon region sits in-between the Nordic and Germanic regions on these dimensions. Our finding is consistent with the lower uncertainty avoidance in Anglo-Saxon SBUs and can also be explained by their more extensive delegation of decision rights.

In prior literature, individualism and power distance have been found to be positively associated, and uncertainty avoidance negatively related, to the proportion of variable compensation (Gomez-Meija & Welbourne, 1991; Segalla et al., 2006; Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004). Despite differences in power distance and uncertainty avoidance between our three regions, we observed no significant variation in the amount of variable compensation.

Following Merchant et al. (2011), due to their higher assertiveness, Germanic and Anglo-Saxon SBUs can be expected to rely more on financial rewards than Nordic SBUs. However, we find that Anglo-Saxon and Nordic SBUs rely more on financial rewards than Germanic SBUs. Although differences in humane orientation between our regions are in line with their different use of financial rewards, it is difficult to come up with convincing arguments why humane orientation would drive this choice. Similarly, although we can expect Nordic SBUs to have a higher preference for non-financial rewards because of their lower assertiveness, we find Anglo-Saxon SBUs relying most on non-financial rewards, followed by Germanic SBUs, and Nordic SBUs using them the least. Some prior literature suggests the use of non-financial rewards may be related to lower power distance (Chiang & Birtch, 2006, 2012; Newman & Nollen, 1996). Our findings do not provide support. Hence, our findings cast some doubts on the usefulness of masculinity and assertiveness to explain the type of rewards, and power distance to explain the use of non-financial rewards, but the GLOBE dimensions do not provide an alternative explanation for these differences.

The findings of Jansen et al. (2009) imply that SBUs in Nordic regions, as relatively non-assertive, base their rewards to a greater extent on non-financial criteria. However, we find that Germanic SBUs, scoring the highest on assertiveness, use non-financial criteria more than Anglo-Saxon SBUs do. Hence, our results do not provide support for assertiveness driving the use of non-financial criteria in reward systems. Anglo-Saxon SBUs’ more extensive use of predetermined, quantitative targets as well as subjectivity in determining subordinate compensation compared to SBUs in other regions is theoretically difficult to link to uncertainty avoidance, on which the Anglo-Saxon region scores lower than the Germanic and Nordic regions. Instead, the differences in incentive determination can also be a logical outcome of Anglo-Saxon SBUs’ stronger emphasis on performance-based pay.

4.5 Cultural controls

Results reported in Table 10 show that job rotation is a requirement for promotions to a higher extent in Anglo-Saxon and Nordic SBUs compared to Germanic SBUs (p < 0.001). With regards to a preference for internal promotions, we find no significant differences. We find that alignment with organizational values in recruitment decisions for managerial positions is more important in Nordic than in Anglo-Saxon and Germanic SBUs (p < 0.01). Anglo-Saxon and Germanic SBUs, however, connect leadership-based performance to promotions and rewards to a larger extent than Nordic SBUs do (p < 0.001). The cultural region is also associated with the extent to which SBUs use socialization activities, such as social events and mentoring programmes. Socialization is used to a higher extent in Anglo-Saxon SBUs to influence subordinates’ behaviour compared to Nordic and Germanic SBUs (p < 0.001). We find no significant differences with regards to the extent to which SBUs’ top management relies on vision and value statements to guide organizational activities.

Prior literature provides some evidence that uncertainty avoidance is associated with an emphasis on internal promotions (Chang & Taylor, 1999). However, we find no consistent differences between lower uncertainty avoidance cultures (Anglo-Saxon) and higher uncertainty avoidance cultures (Germanic and Nordic) with regards to the importance of internal promotions. The higher degree to which rotation between multiple positions is required for promotion in Anglo-Saxon and Nordic regions is consistent with these regions scoring higher on humane orientation than the Germanic region. Rotation allows subordinates to understand various functions and associated challenges, building ability to appreciate others’ viewpoints. It is also likely to create feelings of belonging to an organization as a whole, fostering caring for others. As such, cultures high on humane orientation are more likely to use rotation than cultures low in humane orientation.

The extent to which leadership performance is connected to rewards and promotions can be explained by either power distance or performance orientation. Cultures high in power distance are predicated on strong authority, and as such, leadership is likely to be an important trait of an organization’s MC culture. As performance orientation reflects the degree to which a collective encourages and rewards group members for individual performance, cultural regions scoring high on performance orientation are likely to value leadership activities, typically associated with performance improvement, and incorporate assessments of individual leadership in rewards that have a substantial payoff, including promotion decisions and equity-based rewards. The higher emphasis placed on socialization processes (e.g. training, social events, mentoring) to reinforce SBU values and beliefs by Anglo-Saxon SBUs can relate to the delegation of decision rights.

5 Discussion

We have analyzed how a broad set of MC practices varies across three cultural regions. Out of these three cultural regions, the Germanic and Nordic have not been studied extensively before. Similarly, many of the MC practices included in this study have not been addressed in prior cross-cultural research. We have discussed above how our results compare to existing cross-cultural research in management accounting and how cultural traits based on GLOBE may or may not explain the differences.

The majority of variation in MC practices between the three Western cultural regions that we studied cannot be explained by comparison to GLOBE cultural dimensions. One reason may be that the cultural dimensions operate simultaneously and may create reinforcing or opposing effects on an individual’s preferences for MC practices (Van der Stede, 2003, p. 268). Another plausible explanation is that cultural traits are subordinate to other contingencies as determinants of certain MC practice choices. Although we controlled for many traditional contingency factors, we did not examine whether they explain MC practice choices vis-a-vis culture. Additionally, the cultural traits in some cases may not be sufficiently different to manifest in meaningful differences in MC practices: Western regions are relatively more similar to each other as compared to non-Western regions. This suggests that there may be a certain threshold of differences in cultural dimensions necessary for culture to have a significant effect on the MC practice choices of organizations. Moreover, if observed variation in any one MC practice cannot be explained by culture or any other firm or contextual attribute, it could be that this MC practice is jointly determined with another MC practice. This would indicate that to understand variation in some MC practices we need to understand how they form interdependent systems (Bedford et al., 2016; Grabner & Moers, 2013). We have alluded to this type of reasoning while discussing how certain MC practices might relate to delegation of decision rights (see also Malmi et al., 2020).

We will next discuss two other broad themes that emerge from our findings. First, Anglo-Saxon firms generally put more extensive emphasis on MC practices compared to Germanic and Nordic firms. One reason for this could be the shareholder orientation of the institutional environments that they operate within. This contrasts with the Germanic (Bottenberg et al., 2017; Rose & Mejer, 2003) and Nordic (Thomsen, 2016) institutional environments that are more closely aligned to a stakeholder orientation. While prior research has detailed differences in corporate governance that arise from shareholder and stakeholder contexts, there is little empirical evidence as to how this translates to MC arrangements. However, underpinning the shareholder model are the principles of agency theory, which prefaces high powered incentives and strong control mechanisms to align managerial interests with shareholders (Eisenhardt, 1989). This is reinforced by the primacy of shareholders in legal codes and the strong markets for corporate control. In contrast, the stakeholder model is based more on relationships, rather than the market, as a basis for governance (Freeman et al., 2010). More trust is placed in networks of relationships that provide stakeholders greater involvement in the strategic decision making of the firm, with less emphasis placed on formal governance practices. Accordingly, these orientations may also be reflected in the general emphasis that firms place on MC practices.

Second, our focus in the analysis has been mainly on MC practice differences between the cultural regions. It is equally important to understand which practices are similar across regions despite cultural differences and why this might be the case. Subordinates have a similar degree of autonomy both in developing action plans and setting targets for short-term ends and means in all studied regions. Diagnostic use of both budgets and performance measurement systems as well as the use of non-financial measures for evaluating subordinate performance are the same across regions. In all studied regions, bonuses are of similar size relative to total annual compensation. Similarly, there is no difference regarding the preference to promote external or internal candidates. Furthermore, an emphasis on value statements to reinforce SBU values and norms as well as vision statements to reinforce objectives and purpose appears even among the studied regions.

Employee empowerment has been one key management trend during the past decades (e.g. Potterfield, 1999). Empowerment makes jobs more attractive as it increases subordinates’ ability to influence firm activities. Empowerment can involve autonomy in planning and participation in decision making. The similar degree of autonomy both in developing action plans and setting targets for short-term ends and means in all studied regions might be a result of this general trend of empowerment in Western societies. Regarding diagnostic use of budgets and also non-financial measures, for decades, these have been the core of the curriculum in business and engineering schools in Western societies (consider for instance quality standards, TQM, Six Sigma and Lean, which all emphasize measurement). This may explain why these methods have survived the economic test of time, proving to be efficient in dealing with challenges regarding efficiency and continuous improvement that most organizations face.

With respect to similarities and differences in reward and compensation practices, the management literature argues that competitive forces have changed pay systems from seniority-based to merit-based throughout the world (Gerhart & Newman, 2020). The fact that bonuses appear to be of similar size in all regions could be due to competitive forces. It is common practice by HR professionals to benchmark compensation levels of competing firms. Similarly, textbooks in the compensation field emphasize the importance of figuring out competitors’ pay levels. Although pay systems are today predominantly merit-based and bonuses appear to be of similar size compared to base salary, differences in pay systems are also known to exist. The literature argues that pay systems are determined by economic, institutional, organizational and employee characteristics, where institutional characteristics also include national culture. Gerhart and Newman (2020) suggest that centralized pay setting in EU countries (governments, trade unions) limits organizations’ ability to align pay systems with strategy. Hence, in our study, the differences in compensation and reward practices observed between Anglo-Saxon versus Germanic and Nordic regions may partly be reflective of Anglo-Saxon firms being able to align their pay systems with their strategy due to more decentralized pay setting.

Prior literature provides some evidence that uncertainty avoidance is associated with an emphasis on internal promotions: firms from high uncertainty avoidance cultures fill top positions in foreign subsidiaries with persons from their own culture (Chang & Taylor, 1999). Our focus in this study was not on top positions in foreign subsidiaries, but on recruitment more broadly. Given the ability of HR professionals to screen various aspects of potential candidates, and hence reduce the uncertainty, uncertainty avoidance as a cultural trait is not likely to play a central role in broad promotion practices. Hence, it is not surprising to find promotion practices regarding internal versus external candidates to be similar across cultural regions. A similar emphasis on vision and value statements may again reflect commonly held beliefs in the leadership literature and teaching of business schools, regarding the importance of showing clear goals and objectives as well as emphazising common values for all employees. We argue these may have become like norms in Western business practice.

6 Conclusions

Our study contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, we reveal empirical differences in MC practices in three different Western cultural regions, of which the Germanic and Nordic have not been studied extensively before. Moreover, we reveal differences in many MC practices that have not been examined before in cross-cultural research, including planning and cultural controls. Second, we provide tentative explanations for some observed differences based on the GLOBE cultural dimensions. However, as many of the observed differences are difficult to explain by cultural traits, we suggest that some of these differences are related to other MC practices in use. Third, we find that, Anglo-Saxon firms emphasize many MC practices to a greater extent compared to Germanic and Nordic firms. We ascribe this finding primarily to the prevailing shareholder orientation in the Anglo-Saxon region. Finally, we find a lot of similar control practices among the studied regions despite major differences in many cultural traits between them. These findings may hint towards some norms in business practices, at least in Western societies.

Like in any explorative research, our explanations are tentative and need to be tested and validated in future studies. Similarly, observed differences do not yet suggest any normative recommendations regarding local adaptations of MC practices for firms having operations in foreign countries. As Van der Stede (2003) points out, adaptations are costly. Hence, this study provides only some building blocks for further research to address this local adaptation question.

This study is not without limitations. We relied on a single respondent from each firm and their views on MC practices are subjective. However, for many of the MC practices, subjective instruments are the only way to gain insight into how they are designed and used within firms. We tried to explain observed differences by cultural dimensions relying on GLOBE research. Although we cannot claim that observed differences are by necessity caused by cultural differences, we controlled for a large number of factors normally found to be associated with the variation in MC practices. Further control variables may have provided additional insights to our study. For instance, company-specific variables not controlled for include business life cycle position of the SBU and the age of the company. Further research is needed to confirm or refute these findings, and provide compelling explanations for observed differences.

Despite its limitations, this study provides a number of avenues to develop cultural theory of MC in further studies. In addition to examining which cultural dimensions are strongest to explain MC practice variation, further research can extend our work by assessing the effectiveness of control configurations in different cultures. If some MC practices are used in a similar fashion in many cultures, how should other MC practices be used in different cultures to achieve desired outcomes? Are there a number of viable configurations, suggesting equifinality, or can we define some best practices for certain cultures, or certain sub-groups of organizations within these cultures? It would also be interesting to study a few large multinationals and how they either adjust, or not, their MC practices to local environments, and whether these choices have an impact on the effectiveness of those MC practices used.

Availability of data and material

The survey data are available from Otto Janschek on request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

We use this framework to identify MC practices. Studying how various MC practices are (or are not) interrelated in various cultural regions is beyond the scope of this study.

Both GLOBE categorizations resulted from a multi-method research project exploring relations between national culture, organizational culture and leadership (Dorfman et al., 2012). We rely on the initial GLOBE Culture and Leadership Study (House et al., 2004), in which 160 scholars in 59 countries surveyed 17,300 middle managers in 951 organizations across three industries (financial services, food services and telecommunications).

The ten clusters are Anglo (e.g. Australia, Canada), Confucian Asia (e.g. China, Taiwan), Eastern Europe (e.g. Poland, Russia), Germanic Europe (e.g. Germany, Austria), Latin America (e.g. Brazil, Bolivia), Latin Europe (e.g. Italy, Spain), Middle East (e.g. Egypt, Morocco), Northern Europe (e.g. Denmark, Finland), Sub-Sahara Africa (e.g. Nigeria, Namibia) and Southern Asia (e.g. Indonesia, Thailand).

Scholars of the GLOBE study did not include Norway and Belgium. However, in the GLOBE study, societies are grouped based on religion, language, geography and ethnicity (Gupta & Hanges, 2004). Norway, as part of the Nordic countries, and the Flemish part of Belgium, as part of the Germanic countries, both have similar scores on these variables as those included in the GLOBE study. Norway is a geographic neighbour of Sweden and has historically been linked to the other Scandinavian countries for centuries and therefore shows similar values in religious belief, language and ethnicity (Mensah & Chen, 2012; Schramm-Nielsen et al., 2005). The Flemish part of the Belgian population shares with the Netherlands a part of their history and, like them, speaks a Germanic language and is, therefore, assigned to the cluster ‘Germanic Europe’ (e.g. Knoll et al., 2021; Mensah & Chen, 2012).

While the purpose of the current study is descriptive and therefore uses the entire dataset, we also used parts of our international dataset in two other studies (Greve et al., 2017; Malmi et al., 2020), in which we zoom in on a limited number of MC practices for which we formulated and tested theoretical predictions. In addition, there are also publications using only the Swedish data (Gerdin et al., 2019; Johansson, 2018) and the Danish data (Willert et al., 2017).

The survey was also conducted in Italy and Poland. Within the GLOBE study, Italy is part of the Latin Europe cluster and Poland part of the Eastern Europe cluster. With only one country per cultural region, and a lower number of observations than in the three cultural regions used in the analysis, we excluded observations from these two countries. Consistent with the GLOBE study, 6 firms from the French-speaking part of Belgium and 12 firms from the French-speaking part of Canada were also excluded.

Given the length of the survey, respondents were able to complete questions relating to firm context in their own time. In nine cases, there were significant blocks of responses missing, and we were not able to obtain responses through follow-up procedures. These cases were omitted. Additionally, there was a very small number of missing responses, representing less than 0.3% of the collected data. These missing responses were imputed using the expectations-maximization algorithm. We also conducted the analyses after removing any cases with missing data, and find no substantive effect on our results.

We regularly conversed with one another both prior to and during the implementation of the survey instrument. Semi-annual, face-to-face meetings were also organized, where we discussed survey development and implementation.

The mean number of performance measures for Anglo-Saxon (Nordic, Germanic) SBUs is 5.84 (5.64, 5.06).

There is no need to expect a linear relation between cultural traits and the design and use of MC practices.

The mean proportion in the Anglo-Saxon (Germanic, Nordic) SBUs is 25% (23%, 19%).

References

Abernethy, M. A., Bouwens, J., & van Lent, L. (2004). Determinants of control system design in divisionalized firms. The Accounting Review, 79(3), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2004.79.3.545

Ahrens, T. (1997). Talking accounting: An ethnography of management knowledge in British and German brewers. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(7), 617–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(96)00041-4

Ashkanasy, N. M., Gupta, V., Mayfield, M. S., & Trevor-Roberts, E. (2004). Future orientation. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 282–342). Sage.

Awasthi, V. N., Chow, C. W., & Wu, A. (2001). Cross-cultural differences in the behavioral consequences of imposing performance evaluation and reward systems: An experimental investigation. The International Journal of Accounting, 36(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7063(01)00104-2

Bae, J., Chen, S., & Lawler, J. L. (1998). Variations in human resource management in Asian countries: MNC home-country and host-country effects. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 9(4), 653–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/095851998340946

Baskerville, R. (2003). Hofstede never studied culture. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(01)00048-4

Bedford, D. S., & Malmi, T. (2015). Configurations of control: An exploratory analysis. Management Accounting Research, 27(1), 2–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2015.04.002

Bedford, D. S., Malmi, T., & Sandelin, M. (2016). Management control effectiveness and strategy: An empirical analysis of packages and systems. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 51, 12–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2016.04.002

Bedford, D. S., & Speklé, R. F. (2018). Construct validity in survey-based management accounting and control research. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 30(2), 23–58. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52652

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x

Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., & Roth, K. (2017). An overview of Hofstede-inspired country-level culture research in international business since 2006. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-016-0038-8

Bhimani, A. (1999). Mapping methodological frontiers in cross-national management control research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 24(5–6), 413–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(98)00068-3

Birnberg, J. G., & Snodgrass, C. (1988). Culture and control: A field study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 13(5), 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(88)90016-5

Bisbe, J., Batista-Foguet, J.-M., & Chenhall, R. (2007). Defining management accounting constructs: A methodological note on the risks of conceptual misspecification. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 32(7–8), 782–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.010

Bisbe, J., & Otley, D. (2004). The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(8), 709–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2003.10.010

Bobe, B. J., & Kober, R. (2020). Does gender matter? The association between gender and the use of management control systems and performance measures. Accounting & Finance, 60(3), 2063–2098.

Bogsnes, B. (2009). Implementing beyond budgeting: Unlocking the performance potential. John Wiley & Sons.

Bottenberg, K., Tuschke, A., & Flickinger, M. (2017). Corporate governance between shareholder and stakeholder orientation: Lessons from Germany. Journal of Management Inquiry, 26(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492616672942

Brewer, P. C. (1998). National culture and activity-based costing systems: A note. Management Accounting Research, 9(2), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1006/mare.1998.0077

Brock, D. M., Shenkar, O., Shoham, A., & Siscovick, I. C. (2008). National culture and expatriate deployment. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(8), 1293–1309.

Burns, T., & Stalker, G. (1961). The management of innovation. Tavistock.

Chang, E., & Taylor, M. S. (1999). Control in multinational corporations (MNCs): The case of Korean manufacturing subsidiaries. Journal of Management, 25(4), 541–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(99)00012-4

Chatman, J. A. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393204

Chenhall, R. H. (2003). Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(2–3), 127–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(01)00027-7

Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (1998). The relationship between strategic priorities, management techniques and management accounting: An empirical investigation using a systems approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(3), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(97)00024-X

Chenhall, R. H., & Morris, D. (1995). Organic decision and communication processes and management accounting systems in entrepreneurial and conservative business organizations. Omega, 23(5), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-0483(95)00033-K

Chiang, F. F. T., & Birtch, T. A. (2005). A taxonomy of reward preference: Examining country differences. Journal of International Management, 11(3), 357–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2005.06.004

Chiang, F. F. T., & Birtch, T. A. (2006). An empirical examination of reward preferences within and across national settings. Management International Review, 46(5), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-006-0116-4

Chiang, F. F. T., & Birtch, T. A. (2007). The transferability of management practices: Examining cross-national differences in reward preferences. Human Relations, 60(9), 1293–1330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2005.06.004

Chiang, F. F. T., & Birtch, T. A. (2010). Appraising performance across borders: An empirical examination of the purposes and practices of performance appraisal in a multi-country context. Journal of Management Studies, 47(7), 1365–1393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00937.x

Chiang, F. F. T., & Birtch, T. A. (2012). The performance implications of financial and non-financial rewards: An Asian Nordic comparison. Journal of Management Studies, 49(3), 538–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01018.x

Chow, C. W., Harrison, G. L., McKinnon, J. L., & Wu, A. (2002). The organizational culture of public accounting firms: Evidence from Taiwanese local and US affiliated firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 27(4–5), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(01)00033-2

Chow, C. W., Kato, Y., & Merchant, K. A. (1996). The uses of organizational controls and their effects on data manipulation and management myopia: A Japan vs U.S. comparison. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 21(2–3), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(95)00030-5

Chow, C. W., Kato, Y., & Shields, M. D. (1994). National culture and the preference for management controls: An exploratory study of the firm-labor market interface. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(4–5), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(94)90003-5

Chow, C. W., Lindquist, T. M., & Wu, A. (2001). National culture and the implementation of high-stretch performance standards: An exploratory study. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 13(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria.2001.13.1.85