Abstract

Cities around the world are confronted with the need to put in place climate adaptation policies to protect citizens and properties from climate change impacts. This article applies components of the framework developed by Moser and Ekström (2010) onto empirical qualitative data to diagnose institutional barriers to climate change adaptation in the Municipality of Beirut, Lebanon. Our approach reveals the presence of two vicious cycles influencing each other. In the first cycle, the root cause barrier is major political interference generating competing priorities and poor individual interest in climate change. A second vicious cycle is derived from feedbacks caused by the first and leading to the absence of a dedicated department where sector specific climate risk information is gathered and shared with other departments, limited knowledge and scientific understanding, as well as a distorted framing or vision, where climate change is considered unrelated to other issues and is to be dealt with at higher levels of government. The article also highlights the need to analyze interlinkages between barriers in order to suggest how to overcome them. The most common way to overcome barriers according to interviewees is through national and international support followed by the creation of a data bank. These opportunities could be explored by national and international policy-makers to break the deadlock in Beirut.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Climate change impacts can exacerbate already existing human induced risks at urban and regional level, leading to heat stress, flooding, landslides, water scarcity and storm surges (Wamsler et al. 2013). Urban adaptation to the impacts of climate change has become an integral part of national as well as urban policy (Reckien et al. 2018). Planned adaptation should not be seen as a goal but rather a process through which urban actors formulate, coordinate and implement actions that address vulnerabilities to people and infrastructure, by reducing exposure to risk, the sensitivity to impacts as well as increasing adaptive capacity (Albrecht et al. 2013). Socio-ecological and economic losses occurring in cities due to climate change impacts are often seen as failures in urban planning and management to support more progressive governance of the process of urban adaptation (Dodman and Satterthwaite 2009). Indeed, there is a generalized consensus that the success of planned adaptation is closely related to the commitment and leadership shown by local authorities to respond to climate change (Scott and Storper 2014; Wamsler 2013). Response capacity refers to the broad pool of resources which governmental and non-governmental actors can use to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) and respond to climate variability and change (Adger et al., 2005).

Studies that could help explain the barriers to climate change adaptation planning and of institutional response capacity have been particularly lacking in Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, where they are greatly needed. Adaptation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region overall is particularly understudied, compared to South Asia and Central Africa (Vincent and Cundill 2021). Lebanon has issued three National Communications to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and until a few years ago there were very few official documents addressing this issue. In addition, Beirut does not have a climate change adaptation plan. The process of building a Resilience Master Plan for Beirut had begun in 2013 with support from the World Bank, but was halted by the administration which took office in 2016.

The objective of this article is thus threefold. First, it aims to examine the institutional barriers that are hindering the adaptation process, specifically those occurring in framing climate change as a problem, the gathering of data and information about climatic exposure and impacts, and the re-framing of climate change as a problem on the grounds of this process of data gathering. Second, the article analyzes the vicious cycles of barriers which perpetuate the difficulties to plan for adaptation. The term vicious cycle is often used in systems literature to refer to a system behavior that builds momentum in a negative direction. In this literature, vicious cycles are also known as reinforcing feedback loops (Meadows 2008). A focus on the dynamic entangling of barriers can reveal how vicious cycles perpetuate the inability of cities to plan adaptation, leading to more appropriate strategies to overcome the barriers (Eisenack et al. 2014; Ekström and Moser 2014; Biesbroek et al. 2013). Finally, the article identifies opportunities to overcome these institutional barriers which could be explored by national and international policy-makers to break the deadlock. In the following section, we present the institutional context of climate change in Beirut. The theoretical literature is reviewed in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we present the research methods. Section 5 contains the results, Sect. 6 the discussion, and in Sect. 7, we conclude.

2 Background and context

2.1 Climate change vulnerability in Beirut

Lebanon is part of the MENA region, the world’s most water stressed region (see Fig. 1 below). Climate change is expected to result in sea level rise and increase in heat extremes, which will put intense pressure on already scarce water resources. These in turn will have severe implications for regional food security, livelihoods, public health and large coastal cities like Beirut (Sieghart and Betre 2018). Within the limits of the Municipality of Beirut (MoB) there is an estimated population of 500,000 inhabitants living in an area of 20 km2. This equals 25,000 persons/km2, one of the highest densities in the world (CES-MED, 2017).

By the end of this century, according to projections, Beirut — which is already exposed to coastal storm surges and heat stress — may have 50–60 more days with temperatures exceeding 35 °C, 34 more nights with temperatures exceeding 25 °C, 15–20 more consecutive dry days, and a decrease in precipitation of 120 mm, mainly in the December months (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2011). Beirut may thus end up having 126 hot days per year, putting it just behind Riyadh, the second city in the Arab States in terms of heat stress (Alkantar 2014; see also Waha et al. 2017). Beirut is highly vulnerable to potential damages to infrastructure due to a large percentage of its population living in extreme poverty, the proliferation of informal settlements, and the urban heat islandFootnote 1 (UHI) effect (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2011). The predominantly paved districts of Mazraa, Bachoura or Achrafieh are 6 °C hotter during the summer than vegetated ones, such as the park ‘Horsh Beirut’ (Kaloustian et al. 2016). This situation is worsened by high levels of pollution and a garbage collection crisis threatening coastal and ocean ecosystems.

2.2 Challenges related to institutional capacity

Lebanese politics is highly influenced by regional powers such as Syria, Iran, and Saudi Arabia, and its own domestic religious coalitions, sectarianism, and interest groups tied to the security apparatus, which all vie for power (Halabi 2010; Waterbury 2013). This explains why the country has been politically unstable for most of its existence since gaining independence from the French mandate in 1943. Especially since the civil war of 1990, the main public institutions have engaged in limited legislative activity. This situation also accounts for the chronically weak capacity to deliver quality public services (Goenaga 2016). The situation is not helped by the economic losses incurred due to the effects of increased heat and longer periods of dry weather. In 2015, these losses accounted for USD 800 million per year in the agricultural and food sector alone. The total costs (at 2015 USD currency value) were expected to be equal to 1.9 million by 2020 (equivalent to about USD 1500 per household on average, suggesting that the average cost per household would likely exceed average annual earnings soon), 16.9 million in 2040, and 138.9 million in 2080 (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2015).

In terms of climate change planning at the national level, the only body with any effective responsibilities is the Climate Change Unit, though it is not yet recognized as an official unit under the Ministry of Environment. As for the MoB, according to Kaloustian et al. (2016), there is a lack of appropriate planning, environmental and management acts. Although there are urban planning codes and decrees, these do not consider urban climatology and associated health and environmental risks and impacts. In 2011, the Ministry of the Environment suggested that the MoB should set laws and regulations to discourage new buildings in flood-prone areas along the coastline, and reinforce or relocate existing ones. It also recommended to update building codes and norms so as to minimize risks of collapse or flooding of basements and upper floors, to allow for backup energy systems should power outages affect central power plants, and to strengthen institutions that are responsible for emergency preparedness (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2011). However, there are national level barriers to complying with these demands. According to the Third National Communication (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2016), these barriers include the unavailability, inaccessibility and inconsistency of data and emission factors, lack of cooperation between research bodies, lack of staff and institutional arrangements to mainstream climate change, lack of coordination between institutions to plan and implement mitigation and adaptation policies and projects, and financial resources restraints. These barriers are still the same as those identified in the first GHG national inventory in 1994. The 2016 report also points out that the regional political turmoil results in strategies being implemented in a fragmented manner. Many of these barriers are also documented more generally in the rich literature on the barriers and opportunities for climate change planning, to which we now turn.

3 Institutional barriers constraining climate adaptation planning: a conceptual framework

The process of adapting to climate change is connected to the policy capacity of government organizations and often, at least on paper, it strives to follow a standard policy cycle (Wellstead and Stedman 2015). Moser and Ekström (2010) and Ekström and Moser (2014), for instance, present a “generalized climate process” cycle that is common in many climate change adaptation initiatives as well as programs promoted by the UN-HABITAT (Ruijsink et al. 2015).Footnote 2 Moser and Ekström (2010) suggest an initial phase called ‘Understanding’, referring to how climate change signals are detected and interpreted by institutions and what type of information they gather and how they use it.

The ‘Understanding Phase’ consists of three sub-phases: ‘Problem Detection’ refers to how actors within an institution frame or conceptualize accurately (or not) a climatic hazard (e.g. perceived changes in temperature). ‘Information Gathering and Use’ (e.g. gathering and using data on temperature means and extremes) deepens the detection in a more detailed manner. In the third and final sub-phase, ‘Problem Re-definition’, the climate problem is re-framed by the institution in light of scientific information gathered in the previous phase and grounded in the reality of localized climate variability. This policy process should be iterative, one where cities re-formulate climate exposure and impacts as new scientific evidence is made available. Figure 2 shows the whole cycle as envisioned by Moser and Ekström (2010), with a circle illustrating the ‘Understanding Phase’. This phase is the focus of this paper given the discernible lack of climate adaptation planning in Beirut.

The understanding phase in the adaptation process (black circle) (Source: Authors based on Ekström et al. 2011, p. 15)

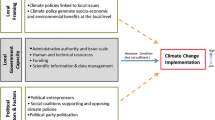

There is a rich literature documenting the presence of institutional barriers, also called obstacles or constraints, creating impasses at municipal level for both adaptation (Biesbroek et al. 2014) and mitigation policy and planning (Burch 2010a, 2010b). Scholars have developed both diagnostic frameworks to characterize barriers at different stages of the policy cycle and their scale of influence (Moser and Ekström 2010), as well as analytical frameworks to understand how international cooperation can alleviate barriers to urban adaptation (Oberlack and Eisenack 2014). Sietz et al. (2011) suggest that institutional barriers arise at three levels. ‘Individual level’ barriers refer to barriers created by the personal attitudes, knowledge, capacity, personality and beliefs of actors within an institution. ‘Organizational level’ barriers refer to the inherent attributes (structural and administrative) of an institution. Finally, ‘Enabling Environment’ level barriers refer to the means and interactions between actors and reflect the societal, economic and political context where adaptation takes place, appreciating how this context may influence, positively or negatively, a municipality’s ability to plan and implement climate change adaptation. The aforementioned barriers may occur in all phases of the climate policy cycle.

As for individual level barriers, actors may simply not be concerned with climate adaptation. For example, according to Ioris et al. (2014), staff in Brazil’s government are fundamentally sceptical of climate change and believe that adaptation is detrimental to economic activity. Other authors point to limited individual knowledge about climate change or skills/capacities (Ekström and Moser 2014; Oberlack 2016), and poor or lack of individual awareness of the risks that climate change poses in a specific location (Füssel and Klein 2006; Ekström and Moser 2014). This has led to low priority assigned to climate threats in cities such as Lima and Santiago de Chile (Eisenack et al. 2014). When leadership or ‘climate champions’ are lacking, stated goals might be missed, and decision-making may be inappropriate (Burch 2010a). On the other hand, excessive leadership concentrated in a few actors is associated with stalled learning, power misuse or unilateral perspectives (Galaz 2005; Garrelts and Lange 2011).

As for barriers at the organizational level, several studies show how scientific data on climate change can be insufficient, unavailable, inaccessible or inadequate for decision making (Füssel and Klein 2006; Ekström and Moser 2014; Oberlack 2016). For instance, in Mozambique, dispersed meteorology forecasting systems do not ensure a timely information dissemination to respond to extreme events (Sietz et al. 2011). Institutional fragmentation or dispersed decision-making authority among various sectors, such as water management, spatial planning, etc. can also become a serious impediment to adaptation (Heinrichs and Krellenberg 2011; Burch 2010a, b; Ekström and Moser 2014; Oberlack and Eisenack 2014). As scientists, experts, researchers and policy makers make sense of climate change, they also create a new body of knowledge which often demands new technical and human resources (e.g. skills and competences) which may be lacking in municipal offices (Füssel and Hildén 2014; Ekström and Moser 2014).

Finally, barriers at the enabling environment level consist of laws and regulations which may be incompatible with the process of climate planning (Oberlack 2016). Communication or coordination issues, both within an institution and among different institutions, may slow down the adaptation process (Sietz et al. 2011). Unclear, fragmented or overlapping responsibilities and mandates about ‘who does what’ can lead to standstills and setbacks (Oberlack and Eisenack 2017; Sietz et al. 2011; Mukheibir et al. 2013). Scarce funding sources, due to financial crisis, inappropriate decision-making routines or mismanagement of funds, is yet another constraint (Ekström and Moser 2014; Sietz et al. 2011). For example, Sietz et al. (2011), state that short-term development goals in Mozambican cities are given priority rather than mainstreaming climate adaptation into development assistance. Lehmann et al. (2013) observed that in Lima, Peru and Santiago de Chile, other public concerns are given higher priority, and rather than in cities, the adaptation process is taking place at the national level. Similarly, in the case of Australia, Mukheibir et al. (2013) found that competing priorities can be traced back to limited funding and staffing, exacerbated by short versus long -term agendas to plan responses.

Some authors have proposed new research agendas which would advance our understanding of the inter-dependency among barriers. In general, Eisenack et al. (2014) indicate that barriers at different levels are interconnected and cannot be understood in isolation. For instance, Oberlack and Eisenack (2014) identify the following reinforcing loop: limited climate change awareness (individual barrier) may lead to little public support for adaptation (enabling environment barrier). Little support from relevant political actors can hamper the process of learning about climate change impacts (organizational barrier) and, in turn, poor learning can reinforce limited awareness (individual barrier). Füssel (2007) suggested that limited awareness among policy-makers and other stakeholders (organizational barrier) can lead to a lack of knowledge about the risks of climate change and to insufficient assessment of climatic risks (enabling environment barrier). Although these authors have suggested entry points related to the interconnections, they recommend to further investigate them since their nature is not fully understood and they can lead to never-ending loops so that barriers are never overcome.

Are there opportunities to overcome these barriers? In fact, it is often implied that institutional barriers represent precisely the opportunity space to pursue opposite pathways and overcome barriers (Ekström and Moser 2014; Mimura 2013; Lehmann et al. 2013; Oberlack and Eisenack 2017; Lehman 2013). Opportunities are defined as “conditions and strategies that enable actors to prevent, alleviate or overcome a specific institutional trap” (Oberlack 2016, p. 814). For instance, lack of individual awareness constitutes a barrier but awareness raising among individuals and the community constitutes the opportunity to overcome it; a lack of climate change knowledge is a barrier, but the organization of ad-hoc conferences or experts’ conferences constitutes an opportunity. In a case study of the San Francisco Bay Area, Ekström and Moser (2014) identified opportunities to overcome barriers. For example, strategic communication and more persuasive ways of framing climate change can get more buy-in from people, which, in turn, addresses communication and coordination issues; boosting education and learning can address knowledge and low awareness issues. Hence, we observe a mirroring effect.

In the case of higher-level or international cooperation on adaptation planning, the ‘mirror effect’ works slightly differently. Since international cooperation can bring several advantages such as generating pressure and momentum, increasing expertise and knowledge, stimulating development of information or allocating financial budgets, it can address a multitude of barriers simultaneously rather than a single one. This opportunity is significant since, it is argued, local governments are not capable of addressing all barriers alone, especially in developing countries (Füssel 2007; Pasquini et al. 2013; Eisenack et al. 2014; Reckien et al. 2015; Oberlack 2016). Yet all this may come with undesirable political economic consequences. International cooperation agencies tend to operate a discursive politics that reconfigures meanings of who is vulnerable or resilient (Mikulewicz 2020). Their interventions can thus reinforce state political machinery and play a role in realigning knowledge and power (Nightingale 2017), and further marginalize minorities (Sovacool et al. 2017), while seldomly fully understanding and building on dynamic contextual circumstances (Chu 2018; Pelling 2011a, 2011b).

To sum up, our conceptual framework draws on the existing evidence of how barriers and opportunities (at the individual, organizational and enabling environment level) emerge and influence the initial “understanding” phase of climate change policy making (which itself can be broken up into the sub-phases of problem detection, information gathering and use, and problem re-definition). In Sect. 5, we will apply this framework to the case of Beirut in order to understand the interconnections between institutional barriers, and how they affect the understanding phase in climate change adaptation planning (see Fig. 3).

4 Methods

To investigate the factors influencing the adaptation process in Beirut, the single case study (the ‘case’ being the MoB) used a mixed method approach composed of a total of ten in-depth semi-structured interviews on the status of adaptation planning with two categories of individuals (Table 1) carried out during four weeks in the period July–August 2017 in Beirut by the first author. The first category includes three members of the Municipal Council of Beirut who provided first-hand information about climate adaptation related matters undertaken by the municipality (elected members of the MoB had been approximately one year in office at the time of the interviews). The second category comprised seven local experts from different sectors, such as the national government or academia working on climate change, urban environmental planning or sustainable development issues in Beirut. Interviews lasted 50 minutes on average and were conducted in English. Interviewees were asked for their informed consent and were granted anonymity. Secondary data were collected from a variety of sources to triangulate and verify information provided by interviewees. The documents include the Atlas du Liban. Les nouveaux défis (Verdeil et al. 2016); an official statement by the Municipal Council on reducing the disaster risk and increasing city resilience (Municipal Council of Beirut City, 2011); a YouTube video on Making Cities Resilient and Disaster Risk Reduction in Beirut (UNDRR 2011); a brochure on the national economic, environment and development study for climate change projects (Republic of Lebanon, 2009); and an online source on politics in Beirut (Winters 2016).

4.1 Research limitations

While we aimed for an equal number of interviewees in the two categories, MoB members were reluctant to be interviewed. In addition, when council members were asked particular questions, for instance about the influence of the private sector on the Municipality’s decisions, they tended to answer very briefly and cautiously. One council member did not allow the interview to be recorded, while another was not willing to go through the full interview guide, thus only key questions were addressed. The second category of interviewees on the other hand, was more open to share information and allocated plenty of time for the interviews. In general terms, the local experts were asked to share their views on how the MoB frames and works on climate change issues.

The interviewees were identified through targeted and snowball sampling, i.e. e-mails were sent to relevant city officials, and local experts in our pre-existing networks were asked to help identify and approach other relevant experts and city officials. Given the overall small number of officials working in the field of climate change adaptation in the MoB, we consider that we reached a sufficient number of relevant interviewees. The fact that the first author was not Beirut-based helped to limit perception biases (in both directions) and forming pre-conceived assumptions about potential barriers. Although we believe that this case study provides rich explanations about the adaptation planning process in Beirut, the findings cannot be generalized to other cities because they are embedded in this specific context (Groeneveld et al. 2014).

4.2 Data analysis

The data analysis comprised the following steps. First, full transcriptions of the interview audio file or written notes were captured in Word documents. Second, using qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti, lines or paragraphs that related to the same topic were coded according to their meaning (e.g. an individual barrier, an opportunity, a framing of climate change, etc.). Coding for competing priorities and lack of interest was differentiated based on who or what the informant was referring to (e.g. administration not pushing climate change onto the agenda or staff not having an interest at the individual level). The context of the Syrian refugee influx and garbage crisis, for example, was a competing priority. Next, based on the coding, sentences provided by different interviewees under the same code were compared to confirm whether information given by one source was backed up by others (triangulation). This resulted in preliminary findings. Fourth, to be able to analyze the occurrence of barriers and opportunities, the number of times they were mentioned was quantified in an Excel frequency table. Based on this occurrence and on the code-related sentences, further analysis and interpretation of data was possible. Finally, based on the data analysis, conclusions were drawn. We now turn to the results.

5 Results

5.1 Institutional barriers

In this section, we explain commonly reported barriers by level, identify the vicious cycles, and outline opportunities to overcome the barriers. As mentioned earlier, the starting point is the fact that while at the national level an unofficial climate change unit was established, a municipal unit and a climate adaptation plan are lacking at the local level. The MoB nevertheless was involved in defining a Resilience Master Plan for Beirut together with the World Bank and the consultancy company BuroHappold Engineering during the administration of Mr. Belal Hamad, former President of the Municipal Council and Mayor of Beirut Municipality. The plan was halted when the municipal administration changed in 2016. Mr. Jamal Itani became the elected new mayor before any climate change intervention could be deployed. Our findings on the barriers help to understand why this happened and why this situation is persisting.

5.1.1 Individual level

At the individual level, there seems to be limited interest about climate change within the municipality. According to some external experts, the municipality’s main focus is on territorial marketing and continued economic growth:

“[…] in Lebanon it’s still largely about how can we have growth at municipal level, how can we bring economic growth in our areas, so this is the main mindset, now, for risk issues for them this is not our problem, it’s the state’s problem, it’s out of our control, out of our capacities, scope.”

“[…] when your focus is only on growth, on territorial marketing being attractive for investment, this is not exactly climate change as a priority at all, it’s another discourse, another paradigm, other tools, other operational approaches, so even when they work on green spaces, the idea of having green spaces has nothing to do with adaptation, potential floods, etc. it’s only to do with minimizing CO2, it’s only to do with making it [the city] more attractive.”

These interviews reveal that the poor individual interest in climate change may be driven by competing priorities within the municipality. We also found a generally limited individual knowledge and understanding of climate change as a problem, which is likely leading to a distorted vision about what dealing with climate change entails, what level of government should address its risks, and how it could be mainstreamed into related projects such as water and energy management, territorial planning, etc. There seems to be distrust in what purposes and whose interests the investments made in green spaces are actually serving, i.e. protecting citizens and properties from flooding and heat or whether they mostly serve to absorb CO2 emissions and neighborhood beautification. This reflects both views found in the current literature about green infrastructure as a resilience approach (Benedict and McMahon 2002; Cherrier et al. 2016; Gill et al. 2007) but also about how green infrastructure can lead to increases in property prices and spatial injustices (Cheng 2016; Shokry et al. 2020). We also found a lack of awareness of activities that contribute to more environmental damage by some municipality members (e.g. garbage flowing directly to the sea from dumps) and of efforts carried out by the MoB to address them.

5.1.2 Organizational level

We found three main clusters of barriers at the organizational level. First, the lack of a specialized local unit or department working on climate change with personnel and expertise is mainly due to the insufficient attention given to climate change (as a result of barriers at the individual level). There have been efforts to constitute a department as part of the Resilience Master Plan, but so far, it has failed to materialize. This might be linked to the perception that the climate problem is thought of as a central government task outside the mandate of local authorities. Second, there is little information available (such as academic climate studies, risk and hazards databases, vulnerability assessments, etc.), and it is not easily accessible to specialists nor to the general public. In addition, we found a reluctance to use the available information due to suspicions about information manipulation, or political controversies such as information being owned by members of rival political parties. Third, we found structural fragmentation both among and within decision making bodies. For example, an interviewee stated:

“the very specific issue about the Municipality of Beirut is that we have two bodies, the executive body and the decision-making body. If these two bodies don’t have the same attitude toward this project it will be a big difficulty, and this is the big challenge […], they need to have the same appetite and the same priorities. The administration should build the capacity of the municipality to handle this project because you still need the resources, the people, the skills, you have to build a new department for disaster risk or something to update the data, to establish a database to document losses from shocks and stresses of the city (…), we need to put a structure in the municipality with a dedicated department with an office.”

Although we couldn’t verify to what extent this two-tier system is responsible for halting the Resilience Master Plan, this structural fragmentation may compound all the three other barriers we mentioned above, by halting or delaying decisions about how and by whom information should be used. This fragmentation may also affect the views on how climate change should best be dealt with, if by creating a specialized department, and considering it a stand-alone issue, or by mainstreaming it across different sectors and departments (Ayers and Dodman 2010; Ruijsink et al. 2015; Mogelgaard et al. 2018).

5.1.3 Enabling environment level

At the level of the enabling environment, the following barriers were found. First, there were more competing priorities in the municipality due to other pressing issues such as the Syrian refugees’ influx, the provision of electricity and water services, the garbage crisis and national security concerns. Second, there is a far-reaching political interference in the municipality’s decision making by private sector interests. The corporation Solidere, a Lebanese joint-stock company who was in charge of planning and redeveloping Beirut Central District, was often alluded to as having a polemic role and over-influence in the political life of Beirut. The local government is highly controlled by this company and Saad Hariri (Prime minister and son of Rafiq Hariri who established Solidere). The overwhelming influence of private sector interests on the municipality’s decisions, linked to corruption issues, is evidenced by the fact that along the Beirut coastline, land and public spaces such as beaches are being illegally occupied by private companies (e.g. in the form of beach resorts), but this is tolerated and facilitated by the municipality. Our findings confirm those by Fawaz (2017) who documented the widespread and ‘normalised’ practice of issuing temporary legal or extra-legal exceptions to building regulations. The final set of barriers at the enabling environment level has to do with inappropriate communication and coordination in the way climate change is transmitted from ministries to the local government. We also found that the ways in which professionals, the scientific community, academics and experts talk about climate change are sometimes not well understood by civil society.

Table 2 shows the institutional barriers and the stage of the adaptation policy cycle they affect. ‘Competing priorities’ was by far the most frequently mentioned barrier, followed by ‘Lack of interest’ and ‘Lack of a specialized department’. These top three barriers correspond to the three different categories of institutional barriers, namely the enabling environment, the individual level and the organizational level respectively. Thus, it can be implied that all three levels play a relevant role in hindering the adaptation process. On the other hand, the most affected stage is the ‘Problem detection’ (the very first sub-phase of the cycle) with twelve barriers, six affect the ‘Information gathering and use’ and three the ‘Problem re-definition’. This means that from the very beginning of the adaptation policy cycle there are issues constraining its continuum.

5.2 Vicious cycles

We now turn to an examination of the interconnections between barriers. Out of the fifteen barriers encountered, there are six that are frequently interconnecting with each other in vicious cycles perpetuating difficulties to plan for adaptation. Figure 4 shows these cycles.

Graphic representation of the most common barriers to adapt to a changing climate in Beirut interacting with other barriers, thus creating vicious cycles. These cycles perpetuate the inability of the Lebanese capital to follow a more comprehensive climate policy planning process that would allow to plan, implement and assess actions. (Source: Authors)

The most interconnections happen between competing priorities in the municipality and lack of individual interest. The former hinders individual interest in climate change, and vice versa, the latter is reflected in climate change not being one of the priorities for the municipality (the larger cycle in Fig. 4). We see that political interference is the root cause of competing priorities and lack of interest, where the importance of climate change is overshadowed by real estate development and its influence on the municipality’s agenda. All together these barriers create the most frequent vicious cycle.

Political interference in the Municipality generates limited knowledge contributing to competing priorities. Political interference and competing priorities, however, also generate other feedbacks in the Municipality, hampering the possibility of having a specialized climate change department, which then leads back to limited climate related knowledge. Limited knowledge of climate risks and impacts facilitates further political interference and a distorted view of the climate as an issue to be dealt with at other government levels or as an issue independent from other development challenges. Limited knowledge also generates feedbacks by allowing for competing priorities to arise as well as limited individual interest and competences. An interviewee, for instance, remarked how the backgrounds and political allegiances of the people elected into the local council affect the presence of the climate change issue on the agenda:

“people that got elected are related to their political parties… it’s not an obligation to have people with good competences (within the Municipality), but you need people inside to have enough understanding and enough scientific background in order to allow them to create the (adaptation) strategy.”

Similarly, the absence of a special unit may also allow for more lack of individual interest and political interference by private sector interests. Lack of a specialized department, limited knowledge, and a distorted vision of climate change can then be considered a derived vicious cycle (the smaller cycle in Fig. 4). Both cycles show some barriers connected through feedbacks.

5.3 Opportunities to overcome barriers to climate change planning

Eleven frequently mentioned opportunities to overcome institutional barriers were identified, some with a greater pertinence than others. Eight are institutional opportunities and three are non-government institutional opportunities. Table 3 shows the opportunities under their corresponding category.

5.3.1 Individual level opportunities

Interviewees stressed that individual awareness of Beirut’s climatic threats, for instance, from a severe flood can trigger the larger pressure needed for the MoB to promote climate adaptation. However, this means that awareness is raised in a reactive manner, i.e. only after an extreme climatic event has taken place and not before. The individual experience of a municipal member and how they may be personally affected is influential in changing their minds about the importance of climate change. Also, as we refer to in Sect. 5.3.4, pressure from political constituents and activists can go a long way in pushing local and national councilors to articulate the climate change challenge (Willis 2020). Interviewees were uncertain about whether the Resilience Master Plan started out by the previous administration was going to be promoted by the Administration which took office in 2016, though some members were lobbying for it in their personal capacity.

5.3.2 Organizational level opportunities

Although there is evidence of two weather stations in the Beirut area (Kaloustian and Diab 2015) and of a national “network of meteorological and atmospheric monitoring systems” (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2011:161), it is clear for interviewees that it is necessary to create a robust local observatory center for climatic data. This center would collect and monitor scientific data and make it easily available and accessible to the general public. In addition, interviewees recommended the establishment of a climate change unit under the MoB involving individuals with expertise and ‘know-how’ on climate change management to facilitate and advance efforts towards the initiation of adaptation action plans. The climate-related data could then be translated by this department into relevant information and advice for policy-making processes.

Additionally, capacity building workshops and educational programs are means to increase the knowledge and awareness of climate change. During the launch of the Resilience Master Plan in December 2013, workshops took place to share progress and information on activities being held, but a more sustained engagement is needed. We see a key role here for the officers within the Municipality who are the most committed to lead the way. Public educational programs in schools, universities as well as in neighborhood spaces could be an important tool to break down understanding barriers among the public and raise awareness of the connections between climate change risks and impacts and issues of waste management and land use planning. These three opportunities: data bank creation, a specialized department and the elaboration of studies, are closely related but they may differ in order of importance. Although generating assessments of climatic risks and vulnerability should be the priority, this may be spearheaded also without a specialized department, as long as there is a team in charge of the coordination among municipal departments. The creation of a data bank may take longer given the sensitivity around ownership and sharing of information, therefore a process to sensitize various departments about data sharing is advisable at the onset.

5.3.3 Enabling environment opportunities

The central government of Lebanon has the capability to mainstream adaptation planning into Beirut. As one of the interviewees suggests: “whenever the central government gives this big push about a certain issue, this is when it becomes a topic at the local level”. Nevertheless, support from international donors can be the most effective means to address adaptation according to interviewees. In collaboration with the municipality, transnational municipal network programs (Fünfgeld 2015) may give an important boost to develop local adaptation strategic plans and investments as they did in the nearby city of Byblos. The National Communications to the UNFCCC, the Conference of the Parties (COP) and climate agreements have, at least, pushed Lebanon to record its commitments in writing. This level of international donor support was the most frequently mentioned opportunity. Climate adaptation planning also requires institutional will and the joint effort of various sectors, such as water and energy, etc. For the MoB to be able to involve these sectors, there must be cooperation. To show willingness on climate and environment issues, interviewees suggested setting up a climate change committee under the leadership of the Ministry of Environment, where every Ministry has a cross-sectoral representation, in order to harmonize actions and make synergies. However, willingness against the background of dysfunctional coordination among municipal institutions will not suffice. Coordination between ministries and a climate change committee will be key for mainstreaming adaptation to the local level.

5.3.4 Non-institutional related opportunities

The case of ‘Beirut Madinati’ is a clear example of how organized civil society in the form of a volunteer-led political campaign puts pressure on political parties to act upon urban issues such as the garbage crisis, or other environment-related ones. Interviewees mentioned the importance of civil society and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to raise environmental awareness:

“…it’s a bottom-up process, we are looking into ways to raise awareness not within the municipality but within society which might put pressure on the municipality, it’s the other way around, it’s not the experts, it’s really the society which can put pressure on the municipality.”

Likewise, climate change (health) risks can be communicated to citizens through short films, documentaries, TV programs, newspapers articles, or the radio. This already happens with the waste disposal issues in Lebanon’s rivers. The MoB can communicate adaptation updates through press conferences and the social media (its website, Facebook, Twitter, etc.). However, this was not done during the initiation of the Resilience Master Plan, where no systematic effort to promote the project was made among the general public, but only within institutional stakeholders. Finally, perhaps ironically, the private sector constitutes an opportunity for the MoB given its economic capacity and specific weight and influence in the public life of Beirut. If this sector wants to, it can promote adaptation planning in collaboration with a strong local government. On the one hand, the private sector commits resources, while on the other, the MoB takes part of the credit for boosting adaptation.

6 Discussion

This study aimed to contribute to the literature on barriers and opportunities in climate adaptation planning by analyzing the city of Beirut in Lebanon, where studies of this kind are missing. The barriers discovered have largely one root cause: the political interference by private sector lobbying, which underlies the presence of competing priorities and the importance individual officers place on climate change. At the individual level, we observed superficial knowledge, doubt about the purposes of climate adaptation options like greening, and poor awareness of the factors that contribute to environmental damage in general. This compounds the understanding that climate change is a separate issue from other sectoral problems. We proposed above that an opportunity to influence this status quo resides in the ability of those individuals who have a better understanding of climate and are lobbying for it to find ways to change the framing of climate change as a complex issue, surely, but one that can be anchored in urban development and planning, without competing with it. This role would be akin to that of fostering ‘policy entrepreneurs’ spanning formal (e.g. government) and informal arenas (Tanner et al. 2019).

There is ample research showing that competing priorities, such as housing, waste management, sanitation and economic growth can come in the way of climate change planning (Anguelovski et al. 2014; Aylett 2015; Carmin et al. 2012; Measham et al. 2011; Mees et al. 2013; Urwin and Jordan 2008). In Beirut, issues such as the Syrian refugee crisis and the garbage crisis are addressed separately, instead of seeing how both are connected to climate change. The 2019 floods that turned the south Beirut suburb of Jnah into rivers of water and sludge, were greatly worsened by garbage clogging drainage, overwhelmed storm drain capacity and aging infrastructure (Anderson 2019). The framing of climate change as a public safety issue or a development issue may have greater resonance and allow for envisioning strategies and interventions that could raise the importance of this issue among local counselors and counter the misconception that climate change is a purely national issue.

Political interference reinforces the presence of competing priorities leading to a lack of individual interest. This political interference is exemplified by the political and problematic influence of the real estate sector on the continued development of Beirut’s coastline. Clientelism, lobbying from rent-seeking public officials tied to the security or military apparatus is a frequent issue in the MENA region (Waterbury 2013), and reducing its influence will likely rely on a different leadership that is less swayed by personal interests. Beirut’s real estate lobby, however, may be forced to change also because their assets are at risk. On the one hand, sea level rise combined with increased chances of coastal storms may jeopardize real estate investments, for the damage incurred by sea-facing properties will trigger higher insurance premiums. On the other hand, the real estate sector can be swayed to retrofit existing buildings if options to do so are made available through comprehensive studies highlighting what the private sector can deliver (Anguelovski et al. 2016). Municipality councilors who are still pushing for the implementation of the Resilience Plan could consider partnering with consulting firms and universities to generate the kind of specific evidence-based research that can weigh risks and benefits of action/inaction and begin to turn the political interference into an opportunity.

At the organizational level, we observed how this political interference coupled with a two-tier municipal system, where the executive branch may stall any action from the decision making branch — can derive another vicious cycle where, in the absence of dedicated staff members or a specialized department, little is done to create a body of knowledge around exposure to different hazards, levels of risk and vulnerability and possible impacts. Similar barriers have occurred in Vancouver and Surrey, Canada (Oulahen et al. 2018), in the San Francisco Bay Area, California (Ekstrom and Moser, 2014), in the Western Cape Province, South Africa (Pasquini et al. 2013) and in different port cities (Valente and Veloso-Gomes, 2019). Our results match with those already identified in 2016 by the Third National Communication to the UNFCCC and the latest report by Lebanon of this kind (MoE/UNDP/GEF, 2016). The report stated crucial barriers such as inconsistency and inaccessibility of climatic data and lack of staff (organizational level), regional political disturbance (enabling environment) and made an urgent call to obtain additional financial resources to overcome these barriers. On this last point, our findings indicate that for the MoB, financial resources do not represent a barrier at all. On the contrary, it is argued by interviewees that Beirut is a very rich municipality in Lebanon. The problem, however, is that economic resources are not assigned to environmental matters, let alone climate change.

An avenue to overcome limited knowledge may be for Beirut to leverage the participation in Transnational Municipal Networks (TMN), which played an important role in scaling up climate mitigation efforts (Fünfgeld 2015) and more recently adaptation efforts in cities of the Global South (Bansard et al. 2017) and North (Reckien et al. 2018). However, research also shows that many large cities are left out of these global networks (Heikkinen et al. 2020) and even among those who do participate, not all are active (Kern and Bulkeley 2009) or gain access to benefits. Yet, the kind of capacity building that comes with these networks could trigger the creation of relevant urban climate risk assessment studies and resilience visions.

As other research has pointed out (Amundsen et al. 2010; Oberlack and Eisenack 2014) the national government can signal to lower levels of government, through designing and communicating national level adaptation policies, how to integrate climate change into disaster risk management and land use regulations, and show the interconnectedness of the climate with other crises, such as migration and waste management. In 2020 the Lebanese national government showed promising efforts towards mitigation by updating their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and in 2017 by hosting the first conversation among stakeholders towards the creation of a National Adaptation Plan of Action (NAPA) (MoE 2017). Yet we caution about the role of NAPAs for they may even strengthen existing competing priorities at the local level if they show a strong bias towards technology, infrastructure and state managed natural resources development, and if these priorities are not shared by lower levels of government or civil society organizations and citizens. Top-down designed policies are known to generate tensions with existing policies and practices at lower tiers of government and hence can turn into a new vicious cycle (Phuong et al. 2018).

While barriers at the international level were outside the scope of this study, financial support from international organizations was perceived as a powerful opportunity to coalescence momentum around climate change, yet Lebanon was not even in the top five countries who received most UNFCCC bilateral, regional and other climate finance in 2015 and 2016 (Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia 2019). This figure, however, is limited and based on self-reporting data from UNFCCC reports, which still lack an adequate system for defining, categorizing and tracking finance (Weikmans and Roberts 2019). Yet, major donors have been distrusting of channeling funds to the Lebanese Government. Lebanon has a complex history with development aid, where the same development agencies that helped the post-war reconstruction were also complicit in the creation of shadow bureaucracies, who are immune to oversight, and have effectively replaced government services in Lebanon (Halabi 2010). So far, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) have supported efforts to generate gender and climate specific guidelines in the agricultural sector. This reinforces the impression that climate adaptation support by international organizations is more focused on rural rather than urban areas (Vincent and Cundill 2021).

Finally, interviewees identified Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) as an actor that plays an important role in holding the city accountable for its garbage crisis and its inability to cope with the Syrian refugee crisis. However, some authors (Karam 2018) maintain that this activism may inadvertently allow the government to remain weak by acting in its place. On the other hand, given that CSOs in the MENA region are facing renewed government crackdowns after the experience of the “Arab Spring” of 2011, their real power and ability to influence governments remains to be seen (Halawa 2020).

7 Conclusion

In this article, we advance an understanding of the dynamic nature of barriers to government planning for climate change adaptation in the Municipality of Beirut (MoB). The purpose of this research was to identify institutional barriers that hinder the understanding of climate change adaptation within the MoB, to explore their inter-dependencies (Eisenack et al. 2014), and to outline possible opportunities to overcome them. In the case of Beirut, we posit two main groups of vicious cycles, one containing two of the most frequently occurring barriers (Fig. 4): competing policy priorities which are framed as separate issues and unrelated to climate change risks, which is generated by a root cause barrier, namely the political interference by private sector actors – in particular, the real estate sector – that further diverts attention and resources away from understanding climate change towards continued urban development. This vicious cycle is also found in studies on African and South American cities (Sietz et al. 2011; Lehmann et al. 2013; Eisenack et al. 2014), but in Beirut competing priorities are not necessarily traceable to limited municipal funding or staffing (Mukheibir et al. 2013). We posit that a second vicious cycle is derived from feedbacks between competing priorities and political interference causing the absence of a dedicated department where sector specific climate risk information is gathered and shared with other departments. In turn, this influences the level of understanding about climate challenge and the possibility of framing it as integral to other urban development issues and as a concern that the municipality can lead the way on. To be clear, the ways in which municipalities decide to integrate climate concerns vary across the world, from considering it a stand-alone issue to sectoral mainstreaming (Ayers and Dodman 2010; Mogelgaard et al. 2018), but the development of municipal skills and competences to understand climate exposure, risk and vulnerability need to be a deliberate effort by the municipality. This can happen even when the influence of the real estate sector on coastal development around the world continues to have important vulnerability implications (Herreros-cantis et al. 2020; Shokry et al. 2020), and even when coupled with a municipality highly divided by sectarianism and clientelism, like Beirut. We showed how some municipal officers recognize the potential for subverting these barriers by making changes at both the organizational and enabling environment levels, in order to support the lobbying efforts of a dispersed, but committed, group of individuals within the administration. Although the political party in power at the time of this study did not hint at a great momentum for climate change to be addressed, it does not mean that Beirut cannot address this challenge in the future. On the contrary, political leaders and municipal bureaucrats in Beirut will have to, by necessity, realize that the impacts of climate change that the city already experiences, will further destabilize the socio-economic fabric of the city. We recommend to future researchers investigating challenging locations such as Beirut, to frame climate change in a way that addresses other critical issues such as health co-benefits from climate policies in order to attract the attention of local decision-makers. A practical yet comprehensive approach for latent issues like the garbage crisis, air and water pollution, electricity shortages, heat waves, etc., that has co-benefits for climate is more likely to be politically palatable, as these are everyday pressing problems in Beirut. We also recommend to further investigate virtuous cycles of opportunities that can break through barriers to boost climate adaptation planning in the MENA region.

Data availability

Upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The term ‘urban heat island’ “describes urbanized or built-up areas that are hotter than nearby non-urbanized areas due to the fact that urban areas typically have darker surfaces and less vegetation than semi-urban and non-urban surroundings” (Kaloustian et al., 2016, p. 72).

For the European Union Adaptation Support Tool, see https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu/knowledge/tools/adaptation-support-tool

References

Adger WN, Arnell NW, Tompkins EL (2005) Adapting to climate change: perspectives across scales. Global Environ Chang 15:75–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.03.001

Albrecht M, Blok A, Bulkeley H, Corry O, Death C, Eden S, Fall JJ, Hargreaves T, Jones R, Kortelainen J (2013) Governing the Climate: New Approaches to Rationality. Cambridge University Press, Power and Politics

Alkantar B (2014) Impact of climate change on MENA region to be ‘catastrophic’ by 2050. Available at: http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/22829. Accessed 15 June 2017

Amundsen H, Berglund F, Westskog H (2010) Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation—a question of multilevel governance? Environ Plan 28:276–289

Anderson , F. (2019). Lebanese counting the cost after huge flooding in Beirut. Middle East Eye. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/lebanese-counting-cost-after-huge-flooding-beirut. Accessed 28 Apr 2021

Anguelovski I, Chu E, Carmin J (2014) Variations in approaches to urban climate adaptation: experiences and experimentation from the global South. Global Environ Chang 27:156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.05.010

Anguelovski I, Shi L, Chu E, Gallagher D, Goh K, Lamb Z, Reeve K, Teicher H (2016) Equity impacts of urban land use planning for climate adaptation: critical perspectives from the global north and south. J Plann Educ Res 36:333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16645166

Ayers J, Dodman D (2010) Climate change adaptation and development I: The state of the debate. Prog Dev Stud 10(2):161–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/146499340901000205

Aylett A (2015) Institutionalizing the urban governance of climate change adaptation: results of an international survey. Urban Clim 14:4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.005

Bansard JS, Pattberg PH, Widerberg O (2017) Cities to the rescue? Assessing the performance of transnational municipal networks in global climate governance. Int Environ Agreements 17(2):229–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9318-9

Benedict MA, McMahon ET (2002) Green infrastructure: smart conservation for the 21st century. Renew Resources J 20(3):12–17. https://doi.org/10.1553/giscience2016_01_s176

Biesbroek GR, Klostermann JEM, Termeer CJAM, Kabat P (2013) On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg Environ Change 13:1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0421-y

Biesbroek GR, Termeer CJAM, Klostermann JEM, Kabat P (2014) Rethinking barriers to adaptation: mechanism-based explanation of impasses in the governance of an innovative adaptation measure. Global Environ Change 26:108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.004

Burch S (2010a) Transforming barriers into enablers of action on climate change: insights from three municipal case studies in British Columbia Canada. Global Environ Change 20:287–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.009

Burch S (2010b) In pursuit of resilient low carbon communities: An examination of barriers to action in three Canadian cities. Energy Policy 38:7575–7585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.06.070

Carmin J, Anguelovski I, Roberts D (2012) Urban climate adaptation in the Global South planning in an emerging policy domain. J Plan Educ Res 32(1):18–32

CES-MED (Cleaner energy saving Mediterranean cities) (2017) Lebanon municipality of Beirut sustainable energy action plan (SEAP). [Online] Beirut: European Union: Available at: https://www.ces-med.eu/publications/lebanon-municipality-beirut-sustainable-energy-action-plan-seap [Accessed 07 May 2019]

Cheng, C. (2016). Spatial Climate Justice and Green Infrastructure Assessment: a case study for the Huron River watershed, Michigan, USA. GI_Forum, 1, 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1553/giscience2016_01_s176

Cherrier J, Klein Y, Link H, Pillich J, Yonzan N (2016) Hybrid green infrastructure for reducing demands on urban water and energy systems: a New York City hypothetical case study. J Environ Stud Sci 6(1):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-016-0379-4

Chu EK (2018) Urban climate adaptation and the reshaping of state–society relations: the politics of community knowledge and mobilisation in Indore. India Urban Stud 55(8):1766–1782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016686509

Dodman D, Satterthwaite D (2009) Institutional capacity, climate change adaptation and the urban poor. IDS Bulletin 39(4):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00478.x

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. (2019). Climate Finance in the Arab Region (p. 83). United Nations.

Eisenack K, Moser SC, Hoffmann E, Klein RJT, Oberlack C, Pechan A, Rotter M, Termeer CJAM (2014) Explaining and overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation. Nat Clim Change 4:867–872. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2350

Ekström JA, Moser SC, Torn M (2011) Barriers to climate change adaptation: a diagnostic framework. [Online] Berkeley: California Energy Commission: Available at: https://www.energy.ca.gov/2011publications/CEC-500-2011-004/CEC-500-2011-004.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2019]

Ekström JA, Moser SC (2014) Identifying and overcoming barriers in urban climate adaptation: case study findings from the San Francisco Bay Area California, USA. Urban Clim 9:54–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2014.06.002

Fawaz M (2017) Exceptions and the actually existing practice of planning: Beirut (Lebanon) as case study. Urban Studies 54(8):1938–1955. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016640453

Fünfgeld H (2015) Facilitating local climate change adaptation through transnational municipal networks. Curr Opin Env Sust 12:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.10.011

Füssel HM (2007) Vulnerability: a generally applicable conceptual framework for climate change research. Global Environ Change 17:155–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.05.002

Füssel HM, Hildén M (2014) How Is Uncertainty Addressed in the Knowledge Base for National Adaptation Planning? In: T. Capela Lourenço, et al., eds. 2014. Adapting to an Uncertain Climate. Springer International Publishing, pp. 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04876-5_3

Füssel HM, Klein RJT (2006) Climate change vulnerability assessments: an evolution of conceptual thinking. Clim Change 75:301–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-0329-3

Galaz V (2005) Social-ecological resilience and social conflict: institutions and strategic adaptation in Swedish water management. AMBIO 34:567–572. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-34.7.567

Garrelts H, Lange H (2011) Path dependencies and path change in complex fields of action: climate adaptation policies in Germany in the realm of flood risk management. AMBIO 40:200–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0131-3

Gill, S. E., Handley, J. F., Ennos, A. R., & Pauleit, S. (2007, March 13). Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure [Text]. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.33.1.115

Goenaga A (2016) Lebanon 2015: Paralysis in the Face of Regional Chaos. Geographical Overview | Middle East and Turkey. Available at: http://www.iemed.org/observatori/arees-danalisi/arxius-adjunts/anuari/med.2016/IEMed_MedYearBook2016_Lebanon%202015_Amaia_Goenaga.pdf [Accessed 31-oct-2017].

Groeneveld S, Tummers L, Bronkhorst B, Ashikali T, van Thiel S (2014) Quantitative methods in public administration: their use and development through time. Int Public Manag J 18:61–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.972484

Halabi, S. (2010). Propping up the State. Executive. https://www.executive-magazine.com/economics-policy/propping-up-the-state

Halawa, H. (2020). Middle Eastern Environmentalists Need a Seat at the Table. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/middle-eastern-environmentalists-need-seat-table/?agreed=1

Heikkinen M, Karimo A, Klein J, Juhola S, Ylä-Anttila T (2020) Transnational municipal networks and climate change adaptation: a study of 377 cities. J Clean Prod 257:120474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120474

Heinrichs D, Krellenberg K (2011) Climate Adaptation Strategies: Evidence from Latin American City-Regions. In: K, Otto-Zimmermann, ed. 2011. Resilient Cities. Bonn: Springer, pp. 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0785-6_23

Herreros-Cantis P, Olivotto V, Grabowski ZJ et al (2020) Shifting landscapes of coastal flood risk: environmental (in)justice of urban change, sea level rise, and differential vulnerability in New York City. Urban Transform 2:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-020-00014-w

Ioris AAR, Irigaray CT, Girard P (2014) Institutional responses to climate change: opportunities and barriers for adaptation in the Pantanal and the Upper Paraguay River Basin. Clim Change 127:139–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1134-z

Kaloustian N, Bitar H, Diab Y (2016) Urban Heat Island and Urban Planning in Beirut. Procedia Eng 169:72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.10.009

Kaloustian N, Diab Y (2015) Effects of urbanization on the urban heat island in Beirut. Urban Clim 14:154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.004

Karam JG (2018) Lebanon’s Civil Society as an Anchor of Stability. Crown Center for Middle East Studies, 117, pp. 1–10. Available at: https://www.brandeis.edu/crown/publications/middle-east-briefs/pdfs/101-200/meb117.pdf [Accessed 09 March 2020].

Kern K, Bulkeley H (2009) Cities, Europeanization and multi-level governance: governing climate change through transnational municipal networks. JCMS 47(2):309–332

Lehman JS (2013) Volumes beyond volumetrics: a response to Simon Dalbys ‘The Geopolitics of Climate Change.’ Polit Geogr 37:51–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.09.005

Lehmann P, Brenck M, Gebhardt O, Schaller S, Süßbauer E (2013) Barriers and opportunities for urban adaptation planning: analytical framework and evidence from cities in Latin America and Germany. Mitig Adap Strat Global Change 20:75–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-013-9480-0

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer (D. Wright, Ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing.

Measham TG, Preston BL, Smith TF, Brooke C, Gorddard R, Withycombe G, Morrison C (2011) Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: Barriers and challenges. Mitig Adapt Strat Global Change 16(8):889–909

Mees HLP, Driessen PPJ, Runhaar HAC, Stamatelos J (2013) Who governs climate adaptation? Getting green roofs for stormwater retention off the ground. J Environ Plan Manag 56(6):802–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.706600

Mikulewicz M (2020) The Discursive Politics of Adaptation to Climate Change. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 110(6):1807–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1736981

Mimura N (2013) Overview of climate change impacts. In: A, Sumi., N, Mimura., T, Masui, eds. 2011. Climate change and global sustainability: a holistic approach. Tokyo: United Nations University Press, pp. 46–57. https://doi.org/10.18356/796ca095-en

MoE/UNDP/GEF (2011) Lebanon’s Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. [Online] Beirut: s.n.: Available at: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/lebanon_snc.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2019].

MoE/UNDP/GEF (2015) Economic Costs to Lebanon from Climate Change: A First Look. [Online] Beirut: s.n.: Available at: http://climatechange.moe.gov.lb/viewfile.aspx?id=228 [Accessed 13 May 2019].

MoE/UNDP/GEF (2016) Lebanon’s Third National Communication to the UNFCCC. [Online] Beirut: s.n.: Available at: http://climatechange.moe.gov.lb/viewfile.aspx?id=239 [Accessed 13 May 2019].

MoE. (2017). Advancing a National Adaptation Plan for Lebanon. Climate Change. http://climatechange.moe.gov.lb/newsnap. Accessed 28 Apr 2021

Mogelgaard, K., Dinshaw, A., Gutiérrez, M., Preethan, P., & Waslander, J. (2018). From planning to action: mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/publication/climate-planning-to-action. Accessed 28 Apr 2021

Moser SC, Ekström JA (2010) A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proc Nat Acad Sci 107:22026–22031. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1007887107

Mukheibir P, Kuruppu N, Gero A, Herriman J (2013) Overcoming cross-scale challenges to climate change adaptation for local government: a focus on Australia. Clim Change 121(2):271–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0880-7

Municipal Council of Beirut City (2011) Official statement made by Nada Yamout, Councillor of Beirut City, Lebanon, at the third session of the global platform for disaster risk reduction. Available at: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/globalplatform/officialstatementglobalplatform2011.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2017

Nightingale AJ (2017) Power and politics in climate change adaptation efforts: Struggles over authority and recognition in the context of political instability. Geoforum 84:11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.05.011

Oberlack C (2016) Diagnosing institutional barriers and opportunities for adaptation to climate change. Mitig Adapt Strat Global Change 22:805–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-015-9699-z

Oberlack C, Eisenack K (2014) Alleviating barriers to urban climate change adaptation through international cooperation. Global Environ Change 24:349–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.08.016

Oberlack C, Eisenack K (2017) Archetypical barriers to adapting water governance in river basins to climate change. J Institutional Econ 14:527–555. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137417000509

Oulahen G, Klein Y, Mortsch L, O’Connell E, Harford D (2018) Barriers and Drivers of Planning for Climate Change Adaptation across Three Levels of Government in Canada. Plan Theory Pract 19(3):405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1481993

Pasquini L, Cowling R, Ziervogel G (2013) Facing the heat: barriers to mainstreaming climate change adaptation in local government in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Habitat Int 40:225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.05.003

Pelling, M. (2011a). Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation (p. 204). Routledge.

Pelling M (2011b) Urban governance and disaster risk reduction in the Caribbean: the experiences of Oxfam GB. Environ Urban 23(2):383–400

Phuong LTH, Biesbroek GR, Wals AEJ (2018) Barriers and enablers to climate change adaptation in hierarchical governance systems: the case of Vietnam. J Environ Pol Plan 20(4):518–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1447366

Reckien D, Flacke J, Olazabal M, Heidrich O (2015) The Influence of drivers and barriers on urban adaptation and mitigation plans—an empirical analysis of European cities. PloS One 10(8):e0135597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135597

Reckien D, Salvia M, Heidrich O, Church JM, Pietrapertosa F, Gregorio-Hurtado SD, D’Alonzo V, Foley A, Simoes SG, Lorencová EK, Orru H, Orru K, Wejs A, Flacke J, Olazabal M, Geneletti D, Feliu E, Vasilie S, Nador C, Krook-Riekkola A, Matosović M, Fokaides PA, Ioannou BI, Flamos A, Spyridaki NA, Balzan MV, Fülöp O, Paspaldzhiev I, Grafakos S, Dawson R (2018) How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J Clean Prod 191:207–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.220

Republic of Lebanon, MoE and AUB (2009) National Economic, Environment and Development Study (NEEDS) for Climate Change Project. Country Brief Lebanon. Available at: http://website.aub.edu.lb/ifi/public_policy/climate_change/Documents/publications/20091208ifi_cc_NEEDS_CountryBrief_Lebanon.pdf [Accessed 28 August 2017]

Ruijsink, Saskia, Olivotto, V., Sharma, S., & Gianoli, A. (2015). Integrating Climate Change into City Development Strategies (CDS) (p. 66). UN-Habitat. http://unhabitat.org/books/integrating-climate-change-into-city-development-strategies/

Scott AJ, Storper M (2014) The nature of cities: the scope and limits of urban theory. Int J Urban Reg Res 39:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12134

Shokry G, Connolly JJ, Anguelovski I (2020) Understanding climate gentrification and shifting landscapes of protection and vulnerability in green resilient Philadelphia. Urban Clim 31:100539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2019.100539

Sieghart LC, Betre M (2018) “Climate Change in the MENA: Challenges and opportunities for the world’s most water stressed region,” MENA Knowledge and Learning 164, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/894251519999525186/pdf/123806-REVISEDBLOG-CC-REGION-QN-002.pdf [Accessed 13 May 2019]

Sietz D, Boschütz M, Klein RJT (2011) Mainstreaming climate adaptation into development assistance: rationale institutional barriers and opportunities in Mozambique. Environ Sci Pol 14:493–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2011.01.001

Sovacool BK, Linnér BO, Klein RJT (2017) Climate change adaptation and the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF): qualitative insights from policy implementation in the Asia-Pacific. Clim Change 140(2):209–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1839-2

Tanner T, Zaman RU, Acharya S, Gogoi E, Bahadur A (2019) Influencing resilience: the role of policy entrepreneurs in mainstreaming climate adaptation. Disasters 43(Suppl 3):S388. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12338

UNDRR (2011) Nada Yamout - making cities resilient. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pob7A60m0lg. Accessed 1 Aug 2017

Urwin K, Jordan A (2008) Does public policy support or undermine climate change adaptation? Exploring policy interplay across different scales of governance. Global Environ Change 18(1):180–191

Valente S,Veloso-Gomes F (2019) Coastal climate adaptation in port-cities: adaptation deficits, barriers, and challenges ahead. J Environ Plan Manag 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1557609

Verdeil E, Faour G, Hamze M (2016) Atlas du Liban: Les nouveaux défis. CERI - Centre d’études et de recherches internationales, Sciences Po, CNRS - Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.ifpo.10709

Vincent K, Cundill G (2021) The evolution of empirical adaptation research in the global South from 2010 to 2020. Climate and Development, 0(0), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2021.1877104

Waha K, Krummenauer L, Adams S et al (2017) Climate change impacts in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region and their implications for vulnerable population groups. Reg Environ Change 17:1623–1638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1144-2

Wamsler C (2013) Managing risk: from the United Nations to local-level realities or vice versa. Clim Dev 5:253–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2013.825203

Wamsler C, Brink E, Rivera C (2013) Planning for climate change in urban areas: from theory to practice. J Clean Prod 50:68–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.008

Waterbury, J. (2013). The Political Economic of Climate Change in the Arab Region (Research Paper Series, p. 53) [Arab Human Development Report]. UNDP - Regional Bureau for Arab States.

Weikmans R, Roberts JT (2019) The international climate finance accounting muddle: Is there hope on the horizon? Clim Dev 11(2):97–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1410087

Wellstead A, Stedman R (2015) Mainstreaming and beyond: policy capacity and climate change decision-making. Michigan Journal of Sustainability 3. https://doi.org/10.3998/mjs.12333712.0003.003

Willis R (2020) The role of national politicians in global climate governance. Environ Plan 3(3):885–903. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619887464

Winters J (2016) Beirut, whose city? Available at: http://harvardpolitics.com/world/beirut-whose-city/. Accessed 22 Jul 2017

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following individuals and institutions for their support and cooperation: our interviewees, the National Council for Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACYT), the Bank of Mexico through the Fondo para el Desarrollo de Recursos Humanos (FIDERH), Ghaleb Faour, Line Rajab, Hala Abi Saad and Leonardo Zea Choy.

Funding

The Mexican National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zea-Reyes, L., Olivotto, V. & Bergh, S.I. Understanding institutional barriers in the climate change adaptation planning process of the city of Beirut: vicious cycles and opportunities. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 26, 26 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-021-09961-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-021-09961-6