Abstract

Informal caregivers are a population currently in the shadows of disaster risk reduction (DRR), and yet essential to the provision of healthcare services. This scoping review explored the literature to understand issues related to informal caregiving and promising practices to support resilience for disasters. Following guidelines for scoping review as outlined by Tricco et al. (2016), relevant publications were identified from five major databases—Medline, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Relevant studies referenced informal caregiving and disasters for a variety of population groups including children, people with disabilities or chronic illnesses, and older adults. Studies were excluded if they discussed formal caregiving services (for example, nursing), lacked relevance to disasters, or had insufficient discussion of informal caregiving. Overall, 21 articles met the inclusion criteria and were fully analyzed. Five themes were identified: (1) the need for education and training in DRR; (2) stressors around medication and supply issues; (3) factors affecting the decision-making process in a disaster; (4) barriers leading to disaster-related problems; and (5) factors promoting resilience. Recommended areas of strategic action and knowledge gaps are discussed. Many informal caregivers do not feel adequately prepared for disasters. Given the important role of informal caregivers in healthcare provision, preparedness strategies are essential to support community resilience for those requiring personal care support. By understanding and mobilizing assets to support the resilience of informal caregivers, we also support the resilience of the greater healthcare system and the community, in disaster contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In 2012, more than 8 million residents in Canada aged 18 years and over provided care to a relative or friend with a chronic health issue (Turcotte 2013). Most informal caregivers are women, with upwards to 80% of family caregivers in Canada being women (Romanow 2002; Grant et al. 2004). In this study, informal caregiving refers to unpaid care and support provided by family or friends, specifically for needs beyond that of general childcare, such as chronic health issues or diseases (Hollander and Chappell 2002; Grant et al. 2004).

Informal caregivers are an invaluable resource who provide ongoing care, support, navigation of complex healthcare systems, and advocacy for people in need of help with daily living, often with little to no training (Schulz and Eden 2016). Informal caregivers are often undervalued in the important supports that they provide for health and social service systems (Grant et al. 2004). Caregiving is physically and mentally demanding, time consuming, complex, and expensive (Sinha et al. 2016; Stall 2019). Policymakers recognize the burden of caregiving on the health of informal caregivers and are examining strategies to improve the contexts for informal caregivers and their families (Fast 2015). However, an ongoing gap in these strategies is including the importance of and need for disaster preparedness for, and by, informal caregivers for themselves, their families, and their care recipients.

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 (UNDRR 2015) recommends an “all-of-society” approach to disaster risk reduction (DRR). It is known that families of people with chronic health conditions in need of care have more stressful experiences during a disaster (White 2006; Peek and Fothergill 2008) and are not adequately prepared for disasters (O’Sullivan et al. 2012; Sakashita et al. 2013). Disasters may also leave medical systems vulnerable, requiring informal caregivers to increase care delivery (Ozaki et al. 2017). Therefore, informal caregivers and care recipients should be a part of the all-of-society narrative to promote their health and resilience, and reduce risks in disasters.

To explore the experience of informal caregiving in disasters, a population health perspective lens will be used. A population health perspective focuses on the study of health status and determinants of health (Young 2005). The overarching goal of population health interventions is to address underlying social, economic, and environmental conditions to shift the distribution of health risk (Hawe and Potvin 2009), reduce health inequities (Public Health Agency of Canada 2012), and prevent disease and promote health (Young 2005).

This study asks the overarching research question: What is known from the existing literature about informal caregiving throughout the different phases of disaster? In addition, we approached this study with the following objectives: (1) to examine barriers and facilitators to informal caregiving in the context of disasters; (2) identify gaps in knowledge; and (3) to propose areas of strategic action to support informal caregiving in disasters based on promising practices in the literature. Our main objective is to explore informal caregiving across phases of disaster to identify promising practices in the literature and understand the experience of informal caregivers and their families.

2 Methods

The approach for this study is a scoping review, which allows the breadth of knowledge and practice in an emerging field of research to be explored, making the method well suited for synthesizing literature related to informal caregivers in the context of disasters (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010; Armstrong et al. 2011; Peters et al. 2015; Tricco et al. 2016). A scoping review allows the inclusion and mapping of different types of evidence, including quantitative and qualitative studies (Dixon-Woods et al. 2006). Arksey and O’Malley (2005) identify four reasons to undertake scoping reviews—this review addresses three of them. First, we use it to examine the extent, range, and nature of research on informal caregiving in disasters; second, to summarize and disseminate research findings; and third, to identify existing gaps in the field. Informal caregiving was considered across all phases of the disaster management cycle including literature on prevention/mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery, and an all-hazards approach was used to include a wide spectrum of disaster contexts including natural hazard-related disasters, human-made disasters, and humanitarian crises. Our protocol was developed using the scoping review methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and further refined by Peters et al. (2015) and Tricco et al. (2016). In the most recent publication, Tricco et al. (2016) compared the methods of published scoping reviews to those outlined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al. 2015). Based on these guidelines, our scoping review follows the subsequent methods: (1) creating an a priori protocol and review design; (2) identifying relevant studies with two reviewers independently screening titles/abstracts and full-text articles using a study flow diagram; and (3) using a predefined charting form.

2.1 Creating an a Priori Protocol and Review Design

Our protocol was developed prior to conducting the scoping review, and defined the research question, objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, search terms, and databases to be searched (Peters et al. 2015; Tricco et al. 2016). The research question and objectives were previously outlined.

2.1.1 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We focused our inclusion criteria to capture literature on informal caregiving in disasters with a variety of populations and disaster situations. Studies were included when informal care was provided to children, adults, or older adults with chronic illness or disabilities. Similarly, studies conducted in any disaster context such as humanitarian crises, natural hazard-related, and human-made disasters were included. During the title/abstract screening stage, reviewers were instructed to include a study if the disaster context or caregiving context was ambiguous (for example, abstract used the term caregiver without defining whether they meant formal or informal caregiving, or general parental caregiving). These ambiguous studies were sorted in the full-text screening.

We excluded publications that focused on: formal caregiving services (for example, nursing or home care services); institutional-based care (for example, emergency departments, nursing homes); clinical medicine or pharmaceuticals; general childcare responsibilities for children without functional limitations; informal caregiving without a disaster context; post-traumatic stress disorder, or disabilities acquired during a previous disaster, without reference to providing care for these acquired functional limitations in the context of a new real (or hypothetical) disaster; and when the study discussed neither informal caregiving, nor disasters. All types of primary studies were included (that is, quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods) and secondary studies (that is, scoping, systematic, and meta-analyses), while conference abstracts were excluded due to lack of content to determine eligibility for the scoping review. Studies were also excluded if they were not available in English.

2.1.2 Search Strategy

The search strategy was designed to identify relevant publications from the following five major databases: Medline, Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Databases were searched using truncated search terms related to different types of disaster situations (for example, disaster, earthquake, contingency planning, and so on) and truncated variations on the term informal caregiving (for example, caregiver, family caregiver, and so on). See Table 1 for the search strategy as applied to Medline. The search string was based on a Boolean approach in which synonyms for different types of disaster situations, and synonyms for informal caregiving, were combined by the operator “OR.” Disaster synonyms were combined with informal caregiving synonyms by the operator “AND.” MeSH terms were used in Medline, PubMed, and Embase to further increase the pool of results. Medline was used to do a preliminary search to refine search terms before adapting the search string to other databases. No date limit was set in any database to explore the breadth of literature on informal caregiving in disaster.

2.2 Identifying Relevant Studies

According to scoping review guidelines, two reviewers are required to independently screen titles/abstracts and full-text articles (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Peters et al. 2015; Tricco et al. 2016). The lead author (CJP) did the primary reviewing at every stage of this study. The initial pilot search through Medline was screened by the lead author (CJP) and an undergraduate research assistant. This secondary reviewer helped refine the search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria by screening 5% of the articles pulled in from the pilot Medline search. Following confirmation of the search strategy, the lead author screened titles/abstracts and full-texts with co-author (KP). Finally, an update of the original search strategy was completed to capture the most recent publications on the research topic. Title/abstract screening and full-text screening were done by the lead author (CJP) and co-author (MD).

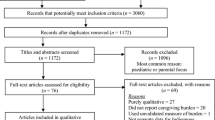

Overall, the scoping review identified 1209 results (before removal of duplicates) using the above search strategy. After removal of duplicates, 845 results were screened by title and abstract. Upon completion of title and abstract screening, 96 results moved on to full-text screening. At this stage, the inclusion and exclusion criteria continued to be refined with the aim of achieving the breadth of available qualitative and quantitative evidence, as recommended in scoping study methodology (Levac et al. 2010). This process resulted in a final cohort of 21 studies that were included in the extraction of data. These studies informed the themes, gaps in the research, and proposed areas for strategic action highlighted in this article. See Fig. 1 for a flowchart illustrating this screening process.

2.3 Using a Predefined Charting Form for Data Extraction

Data analysis involved a descriptive summary and thematic analysis. A data-charting form was developed by the lead author (CJP) and used to extract descriptive data from each study. The charting form had the following categories adapted from those suggested by Peters et al. (2015): authors, year of publication, purpose of the article, study population, methodology, and key findings that relate to the research question. Extraction fields specific to this study included: phase of disaster, caregiving terminology used, whether informal caregivers, care recipients, or both were the focus of the study, barriers and challenges to caregiving in disaster, facilitators to caregiving in disaster, type of disaster, identified needs, and suggested improvements. Arksey and O’Malley (2005) define this phase of data analysis as using a descriptive analytical method to extract contextual or process information from studies.

The thematic analysis was undertaken by collating, summarizing, and reporting on prominent ideas and concepts from the literature (Arksey and O’Malley 2005; Levac et al. 2010). Thematic construction was used to provide an overview of the breadth of the literature on informal caregiving in all phases of disasters. As recommended by Levac et al. (2010), we concluded thematic analysis with consideration of the implications of the study within the broader context of research, policy, and practice by providing recommended areas for strategic action.

3 Results

Overall, 21 articles met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed using descriptive and thematic analysis. Five themes were identified: (1) the need for education and training in DRR; (2) stressors around medication and supply issues; (3) factors affecting the decision-making process in a disaster; (4) barriers leading to disaster-related problems; and (5) factors promoting resilience. We first present the descriptive summary, followed by discussion of the five themes.

3.1 Descriptive Summary

Here we provide a descriptive review of the research design and methodologies for studies on informal caregiving in DRR. The following sections provide a review of publication dates, terminology used to identify informal caregivers (that is, unpaid support), functional needs of care recipients, care provider gender, care provider/care recipient relationship, phases of disaster discussed, type of disaster, research design, and data collection tools. Table 2 provides a summary of the nature of the literature.

(1) Publication date All studies were published between 2006 and 2019. It is important to note that we did not limit the database searches by date, and as such this reflects a lack of publications prior to 2006 on informal caregiving in disasters. As Oliva et al. (2013) note, there was an increase in disaster planning for older adults, and children and adults with functional needs post-Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Hurricane Katrina spurred this population-specific interest in disaster planning because of the disproportionate number of fatalities that were from older adults aged 60 and up (Adams et al. 2011).

(2) Terminology used to identify unpaid support work The literature uses an array of terms to indicate the provision of unpaid support (that is, informal caregiving). Most often used is the generic term “caregiver” (n = 16). This term does not give the reader a clear understanding of the population of interest as caregiving can encompass formal service provision, informal caregiving, and general childcare. “Family caregiver” is used by half of the included articles (n = 11), while the term informal caregiver is only used in four (n = 4) studies. Many of the studies flipped back and forth between these terms to say the same thing. This lack of consistent terminology poses a challenge to academics, policymakers, and practitioners alike as it is difficult to differentiate the informal caregiving literature from general childcare, institutional care (for example, emergency departments), and formal caregiving services (for example, homecare nursing services).

(3) Care recipient functional needs There were three major categories of functional needs for care recipients highlighted in the literature: children with disabilities, older adults with disabilities, and people with chronic illnesses. People with chronic illnesses include children, adults, and older adults with chronic illnesses requiring informal care, and was most often the care recipient population of interest in the included studies. One study did not specify a specific functional need as they were interested in understanding the diversity in “medical special needs” disaster shelters (Patton-Levine et al. 2007).

(4) Care provider gender Informal caregiving is gendered in nature with more women providing care than men (Romanow 2002; Grant et al. 2004; Turcotte 2013). As such, we sought to understand how many articles made the distinction between care provider’s gender. Most studies did not specify who was providing care, and thus did not specify a gender (n = 10). However, of the 11 studies that did report a focus on a specific gendered care provider, 10 (n = 10) studies explored female perspectives, while only one (n = 1) study specified an interest in male care providers.

(5) Care provider/care recipient relationship Many different members of a personal support network can act as informal care providers for a care recipient such as spouses, siblings, parents, adult–children, grandparents, and more. While some studies did not specify a specific care provider/care recipient dyad (n = 4), most studies provided information on informal caregiving in dyads in which an adult child provides care to their parents (n = 9), or a spouse supports a spouse (n = 11). Meanwhile, six (n = 6) studies presented informal caregiving from the perspective of a parent supporting their child. Other familial relationships identified include siblings, a daughter-in-law, and a grandmother (n = 8). Finally, two (n = 2) studies identified other non-familial dyads formed between neighbors or friends. Often, studies included several of these care provider/care recipient dyads in one study.

(6) Phases of a disaster Most of the identified literature reported informal caregiving in the context of disaster preparedness (n = 15), followed closely by reporting on the response context (n = 14). Fewer studies focused on the recovery phase (n = 8) and prevention/mitigation phase (n = 7) of disasters. Many studies reported multiple phases in one study.

(7) Type of disaster Most studies (n = 11) did not specify a disaster, choosing to discuss informal caregiving in the context of disasters in general. Studies that did specify a disaster context included hurricanes (n = 5), earthquakes (n = 4), and floods (n = 1).

(8) Research design The informal caregiving in DRR literature is made up of mostly quantitative (n = 7) and qualitative (n = 10) research studies. Only one mixed-methods study was captured in the literature search. A few studies presented quantitative and qualitative analyses of specific interventions (n = 3) to improve disaster preparedness for informal caregivers. Perspective or commentary articles (n = 3) suggested improvements to policy and practice. No systematic reviews of the literature were found.

(9) Data collection tools The most common form of data collection was the use of qualitative interviews (n = 9), followed closely by the use of quantitative questionnaires (n = 7). Only one (n = 1) study was found for each of the following forms of data collection: observation, focus groups, and narrative account. Secondary data were used in two (n = 2) studies, while the perspective and commentary papers used no data collection tools (n = 3).

(10) Informal caregivers as a high-risk population Informal caregivers have not been a major focus throughout the literature on caregiving in disasters, with any research involving informal caregivers discussing them as an addendum to the care recipient. Studies either present concepts relating equally to the informal caregiver and the care recipient, or they discuss the informal caregiver as a lever for disaster preparedness for the vulnerable care recipient. Rarely discussed is the concept of informal caregivers specifically as a high-risk population in disasters.

(11) Study research approach Most studies used a needs-based approach to DRR. A needs-based approach is a deficit model that focuses on the needs and problems of a population, barriers to resilience, and negative experiences of informal caregiving in disasters (Morgan and Ziglio 2007). In population health, the needs-based approach is the dominant lens used. O’Sullivan et al. (2018) were an exception, however, as the purpose of their study was to explore assets and capacities that support resilience of stroke survivors and their caregivers. The outcome of this study was the development of a conceptual model on asset literacy and household resilience following stroke. Christensen and Castaneda (2014) were another exception as they briefly, but explicitly, outlined capabilities that served informal caregivers and care recipients during the 2004–2005 hurricane seasons.

(12) Lack of disaster preparedness and the need for collaboration This scoping review revealed that informal caregivers are not prepared for disasters (O’Sullivan 2009; Allweiss and Albright 2011; Baker et al. 2012; O’Sullivan et al. 2012; Christensen et al. 2013; Heppenstall et al. 2013; Oliva et al. 2013; Sakashita et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Zuurmond et al. 2016). The literature identifies a lack of emergency plans, lack of disaster kits, and lack of awareness of: risks, resources, and the need for disaster preparedness. The literature also calls for promotion of a collaborative approach to support preparedness and resilience among informal caregivers and their families (Sakashita et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Wakui et al. 2017).

3.2 Thematic Analysis

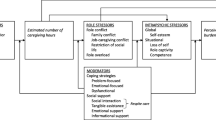

The first iteration of analysis resulted in the identification of nine major themes. These were then reduced to five major themes and their subthemes. The concept map (Fig. 2) provides an illustration of the literature based on these themes. The number in each column header box indicates how many of the 21 articles identified through this scoping review addressed the theme. The key findings for the five themes are described below.

3.2.1 Education and Training

There were several subthemes in the literature relating to education and training, including the need for stakeholder engagement in all phases of disaster. In the identified studies, relevant stakeholders include families of care recipients, first responders, and healthcare providers. Healthcare providers were highlighted as having the resources and expertise to play active roles in information distribution and guidance. For instance, Durrani et al. (2019) highlighted the need for formal medical teams to have training to improve communication between formal caregivers, informal caregivers, and care recipients. Meanwhile, other studies highlighted the need for disaster training and support programs for informal caregivers and care recipients to improve their resilience and independence in the face of disaster (Wakui et al. 2017; Gibson et al. 2018). For example, while some caregivers actively sought disaster-related information on how to prepare for a disaster (Kyota et al. 2018), many caregivers could benefit from tailored disaster preparation awareness programs and support (Baker et al. 2012).

Also reflected in the literature is the need for education and training to be complimented by community support programs, to provide structured support and anticipatory guidance for informal caregivers and their care recipients, in addition to the need to increase respite care during and after disasters (O’Sullivan 2009; Skinner et al. 2009; Allweiss and Albright 2011; Baker et al. 2012; O’Sullivan et al. 2012; Christensen et al. 2013; Heppenstall et al. 2013; Oliva et al. 2013; Sakashita et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Wakui et al. 2017; Ahmadi et al. 2018a; Gibson et al. 2018). Examples of support programs from the literature include incorporating caregivers as key figures in community development of disaster plans (Wakui et al. 2017), funding programs that focus on reuniting care recipients and caregivers in a disaster (Mace and Doyle 2017), social programs for functional need specific disorders and limitations (for example, cancer), such as yoga training to build the caregiver and care recipient’s social support prior to disasters (Durrani et al. 2019).

3.2.2 Medication and Supply Issues

The importance of knowing the care recipient’s medications and understanding how to use medical equipment was another subtheme in the literature. In a study of disaster preparedness among families of older adults reliant on medication, Kyota et al. (2018) found that just over half of the family caregivers in their study stored medications for their care recipient in the event of an evacuation. In another study, chronic health services and prescription refills were the most commonly mentioned services provided in evacuation shelters after Hurricane Katrina (Mace and Doyle 2017). The need for documentation of medication and devices was identified as a necessary preparedness step that informal caregivers should take to adequately prepare to respond to a disaster for themselves and their care recipients (Allweiss and Albright 2011; Baker et al. 2012; Oliva et al. 2013; Sakashita et al. 2013; Ahmadi et al. 2018b).

3.2.3 Factors Affecting Decision-Making Processes

Several studies reflected on factors that contribute to the complex decision-making processes performed by informal caregivers in the context of disasters. The literature primarily focused on decision making during the response phase of disasters, such as the decision to evacuate or shelter-in-place (Gibson et al. 2018). Previous and current social roles of the informal caregiver and care recipient were highlighted as a strong indicator of an informal caregiver’s decision-making effectiveness. Social roles refer to the relationship status between the care recipient and the informal care provider such as mother-daughter, wife-husband, daughter-mother, and so on. For example, according to Ahmadi et al. (2018b), in a granddaughter-grandfather dyad, the granddaughter’s father removed her from the disaster area, making her incapable of continuing to provide care for her grandfather, leaving her grandfather vulnerable.

The status of the care recipient’s health condition also affects the decision-making process (Mace and Doyle 2017). Patients with a progressive disease such as Alzheimer’s disease may be more alert and able to engage in the decision-making process at the beginning of their disease, as opposed to at the end. Paired with a social dynamic in which the informal caregiver may not be accustomed to making decisions on behalf of the care recipient (for example, in a daughter-mother dyad) (Christensen and Castaneda 2014), this change in authority can further affect the decisions made and voices heard. According to Gibson et al. (2018), most caregivers said that their decision to evacuate only came after persuasion from others.

The literature also identifies environmental considerations, that include caregiver and care recipient cohabitation, preparedness actions prior to a disaster, and living in an evacuation zone, as factors that influenced an informal caregiver’s decision to evacuate both parties (Christensen et al. 2013). Socioeconomic status and perceptions of disaster risk also affected evacuation decisions. Social supports were identified as an important factor in the prevention and response phases of a disaster in the decision to move permanently to a less disaster-prone area, or to evacuate temporarily during a response (Green 2006). For example, some care recipients were hesitant to contact their adult children for assistance because they knew their family members lead busy lives (O’Sullivan et al. 2018). Gibson et al. (2018) also highlighted fear, stigma, and untrustworthiness towards emergency shelters and their ability to support the needs of care recipients as factors affecting their decision to evacuate or shelter-in-place.

Finally, the emotional burden of decision making was also briefly discussed in the literature (Green 2006; Skinner et al. 2009; Christensen et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Zuurmond et al. 2016; Wakui et al. 2017). In this case, decision making constitutes an emotional burden because caregivers are forced to make big, potentially life altering decisions within two complex fields: informal caregiving and disasters. For example, Green (2006) discussed the heavy emotional burden she experienced when faced with the decision to continue to evacuate their home during Florida’s hurricane season every year, versus moving permanently to a less disaster-prone region. This was a difficult decision for her because a permanent move, while avoiding the unnecessary risks of yearly evacuation with her daughter with cerebral palsy, would mean losing the extensive social support network her and her daughter had built over the years.

3.2.4 Barriers Leading to Disaster-Related Problems

The literature also focuses on barriers faced by informal caregivers in disaster contexts regarding evacuation in the response phase and ability to prepare for disasters. One barrier to evacuation when caring for someone with dementia, for instance, may stem from the level of engagement of the care recipient; the greater their level of engagement, the greater the difficulty in making decisions in a disaster (Christensen et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014). This is because the care recipient may be engaged, but not fully aware of the situation, thereby not making fully informed suggestions to evacuate or shelter-in-place.

Physical and geographical barriers to disaster response were also addressed. For example, disasters presenting physical constraints such as heavy snowfall, or fallen tree branches across major roadways, prevented some caregiver-care recipient dyads from being able to travel outside disaster zones (Skinner et al. 2009). Fear of social stigma toward care recipient needs, and lack of sufficient support for the care recipients’ medical needs at evacuation shelters were also listed as barriers (Allweiss and Albright 2011; Gibson et al. 2018). For example, during a 2012 earthquake in Iran, older adults in shelters and relief zones felt that disaster relief services were inaccessible for them due to the need to walk long distances, or to stand in lines for hours on end (Ahmadi et al. 2018b). Excessive barriers to evacuation may lead to more care recipients and their families staying in disaster zones, putting themselves in danger and increasing strain on limited formal health and rescue services.

Barriers to disaster preparedness were identified as: lack of education and training on disaster risks, lack of awareness of what items to prepare in advance of a disaster, and how to make a disaster plan that encompasses all care recipient and caregiver needs (O’Sullivan et al. 2012; Kyota et al. 2018). In some cases, caregivers lacked a disaster contingency plan because they assumed they could rely on existing social support networks and formal services during a disaster (O’Sullivan et al. 2012; Sakashita et al. 2013). Others cited no time to think about hypothetical evacuation routes because they were overburdened with work and day-to-day caregiving (Wakui et al. 2017).

Social determinants also factored into a caregiver’s ability to prepare for disasters. Wakui et al. (2017) found that increased preparedness was associated with longer caregiving experience, higher family income, and strong family supports. Disaster preparedness is important to build individual and community resilience in disaster. Disaster education and community support programs could be developed to support informal caregivers and their families, and relieve some of the burden of knowledge acquisition and research from the caregivers. Social support programs can also counter the effects of emotional and psychological isolation that informal caregivers may feel as a result of caregiver burden (Skinner et al. 2009; Christensen et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Zuurmond et al. 2016).

3.2.5 Factors Promoting Resilience

The literature also discussed factors that promoted resilience among the informal caregiving population. Engagement of the care recipient was viewed as both a barrier and facilitator to decision making, depending on the care recipient’s level of awareness about the risks. Care recipients can engage in positive and complementary ways with the informal caregiver and participate in preparation for disaster and evacuation. Positive attitudes, previous caregiving experience, and previous experience with informal caregiving in disasters, were also seen as promoting resilience (O’Sullivan et al. 2018).

Social and formal healthcare support systems were also identified. O’Sullivan (2009) breaks these supports down into types of support: informational, instrumental, and emotional supports. Prior utilization of formal supports and programs were shown to provide caregivers and care recipients with social support that allowed for coping with stress and recovery during and after disasters (Gibson et al. 2018; Durrani et al. 2019). Shelters have also been identified as sources of social support during the response phase of a disaster. In their study examining medical special needs shelters during Hurricane Rita, Patton-Levine et al. (2007) concluded that these shelters were important resources for both the medically needy (care recipients) and non-medically needy (informal caregivers and dependents). They highlighted that these shelters should plan to provide different supports to care recipients and caregivers, while alleviating caregivers of the burden of caring for their medically needy family members.

Life experiences of informal caregivers promote resilience, as they are able to provide new roles through experience and knowledge, in ways such as rescue, guidance, leadership, and psychological support (Ahmadi et al. 2018a, b). Higher socioeconomic status was also highlighted as a factor that promotes resilience, as well as education on disaster preparedness, and support from formal healthcare services (Green 2006; O’Sullivan 2009; Baker et al. 2012; Christensen et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Wakui et al. 2017).

See Table 3 for a summary of the studies on informal caregiving in the context of disaster included in our thematic analysis. The table summarizes the themes across each article, terminology, target populations of care recipients and care providers, disaster contexts, and research design.

4 Discussion

There is little research on informal caregiving in the context of disasters. The purpose of this study was to explore informal caregiving across phases of disaster to identify promising practices in the literature and understand the experience of informal caregivers, their families, and care recipients. This scoping review is novel for exploring informal caregiving in disasters in that it utilized a population health perspective for thematic analysis. Five major themes were identified: education and training; medication and supply issues; factors that affect the decision-making processes; barriers that lead to disaster-related problems; and factors that promote resilience.

The identification of themes in the literature resulted in the recognition of five major themes and one cross-cutting theme: informal caregivers are not prepared for disasters. The gendered nature of informal caregiving was a cross-cutting statistic consistent with other literature on informal caregiving (Romanow 2002; Grant et al. 2004; Turcotte 2013). The gendered nature of informal caregiving should be recognized as an important characteristic of the population of informal caregivers when considering themes and creating plans, policies, and interventions to increase preparedness of informal caregivers in disasters. Most informal caregivers are women (Romanow 2002; Grant et al. 2004; Turcotte 2013) and as such, the burden of risk from informal caregiving falls predominantly on women. The Sendai Framework (UNDRR 2015) emphasizes an all-of-society approach to DRR, which includes improved engagement of women in DRR decision making and activities. By engaging women in DRR, this may help to reduce their risks and those of their care recipients.

Education has been highlighted as an important intervention to promote disaster preparedness knowledge and behavior change. The education and training theme crosscut the largest number of studies in the review. This is not surprising given caregivers’ lack of access to caregiver-specific education and supports for their day-to-day caregiving needs (Stall 2019). It is therefore understandable that they would also be missing this education for disaster specific caregiving contexts.

Lack of education and training points to a need for better disaster preparedness among informal caregivers with the need to educate them on how to prepare for disasters, and educating formal healthcare services on how they can best support informal caregivers in disasters (O’Sullivan 2009; Skinner et al. 2009; O’Sullivan et al. 2012). Ideally, educational initiatives should provide guidance on all-phases of disaster using an all-hazards approach (UNDRR 2015). Educational initiatives should be developed with the country of origin in mind for context. Important recommendations for disaster preparedness education include knowing the risks, making a plan, and getting a kit (Government of Canada 2016). Education on disaster preparedness for informal caregivers should emphasize how to achieve these goals and why they are important to promoting their family’s health and resilience.

The critical need to provide informal caregivers with proper disaster education and training reflects the guidance set out by the Sendai Framework for an all-of-society approach to DRR (UNDRR 2015). Education and information on disaster preparedness should be provided by formal healthcare services already accessed and trusted by informal caregivers and their care recipients (O’Sullivan 2009). Formal health services can play an active role in knowledge dissemination on the risks and importance of disaster preparedness. Research evaluation should accompany the increase in educational initiatives to ensure that there is not only knowledge increase, but behavior change as well.

The literature has identified formal health services as an asset to support informal caregivers in all phases of disaster (O’Sullivan 2009; Skinner et al. 2009; O’Sullivan et al. 2018). Based on this review of the literature, we recommend that formal services be utilized in the following ways to promote education and disaster preparedness: (1) healthcare professionals are a trusted source of information and are in a position to encourage individual disaster preparedness during routine visits through education and knowledge dissemination through pamphlets; (2) services could require clients to create an emergency plan to be kept on file to initiate disaster preparedness behavior in these populations (Christensen and Castaneda 2014); and (3) social workers and other health professionals can give advice on disaster preparedness planning, response, and recovery for the unique contexts of each family. Involving formal health services in the promotion of individual and household disaster preparedness can provide structured support and guidance for informal caregivers seeking advice (O’Sullivan 2009; Skinner et al. 2009).

Regarding medicine and medical supplies, current public and private insurance policies need to be reviewed as they limit the ability of informal caregivers and populations at disproportionate risk to stockpile medication in preparation for an emergency (Allweiss and Albright 2011). Some relaxing of said policies would support the instructions provided by governments on disaster preparedness advising citizens to stockpile medication in case of emergencies. Evacuation shelters should also revisit their policies on medications in shelters as Allweiss and Albright (2011) identified some shelters that do not allow citizens to bring their own medications unless they were in their original containers. Having medication confiscated upon entering a shelter could cause health repercussions and financial set-backs for care recipients. Such policies force care recipients and caregivers to decide whether it is safer to shelter-in-place with access to their medications, or evacuate to shelters where their medication may be confiscated. Shelters should create medication preparedness plans with caregivers and care recipients in their disaster evacuation zones prior to disasters to establish protocols that work for the shelter and evacuees.

Complex decision-making processes are performed by informal caregivers during disasters. Making these potentially life-altering decisions for loved ones in the response phase of a disaster can be emotionally draining, placing extra-burden on caregivers (Green 2006; Skinner et al. 2009; Christensen et al. 2013; Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Zuurmond et al. 2016; Wakui et al. 2017). To mitigate this emotional burden, steps can be taken before a disaster in the prevention and preparedness phases. This includes partnering with healthcare providers and community organizations to create a family emergency plan that outlines the decisions informal caregivers will make given different risk scenarios. This includes decisions such as whether to shelter-in-place, or where to evacuate (Gibson et al. 2018). These decisions require reflecting on caregiver and care recipient social roles (Christensen and Castaneda 2014; Ahmadi et al. 2018b), the health status of the care recipient (Mace and Doyle 2017), and whether or not the care recipient and caregiver live together or separately (Christensen et al. 2013). Local community organizations and healthcare associations can play a role in establishing strong social supports to prevent unnecessary decision-making burdens on informal caregivers and their families by preparing them for disasters. This support could come in the form of formally integrated disaster planning assessment tools such as the one developed and tested by Wyte-Lake et al. (2019) for in-home formal care providers to assist their patients’ families to prepare for disasters. Working in collaboration with these social supports and health service organizations before a disaster can also help reduce the fear, perception of stigma, and untrustworthiness towards shelters and existing emergency management supports (Gibson et al. 2018).

The themes identified in this scoping review revealed the complexity in providing informal care during disasters. The barriers to informal caregiving in disasters are well documented in the literature. The identified barriers span various phases of disaster, including: preparedness, response, and recovery. As previously discussed, lack of education and training is an important barrier to informal caregiving in disaster contexts and should be addressed prior to any disaster (that is, in the preparedness phase). This includes educating caregivers about what formal services might be inaccessible during a disaster and how to adapt their care accordingly. Financially, some families of lower socioeconomic status may be unable to invest in preparing grab bags in preparation for disasters (a common preparedness directive). Financial assistance programs could be put in place to support these families to adequately invest in stockpiling medications, buying non-perishable foods, and buying supplies to prepare for disasters. During the disaster response, social barriers such as fear of stigma, lack of supports in shelters, and physical barriers to accessing shelters, should be addressed. Plans should also be in place for caregivers to know when and how to evacuate, versus shelter-in-place. Finally, lack of social and emotional supports was identified as a barrier in the response phase of a disaster. Addressing these complex barriers will require a multidisciplinary approach between emergency management practitioners, policymakers, healthcare services, and community organizations.

Less salient in the literature are studies on facilitating factors that promote resilience for informal caregivers in disasters. To fill this research gap, a more explicit exploration of facilitators and assets that support resilience and promote health of informal caregivers in disasters, similar to the studies by Christensen and Castaneda (2014) and O’Sullivan et al. (2018), is needed. Recent studies highlight the important role community-based participatory research (CBPR) can have in addressing community resilience (Chandra et al. 2013; O’Sullivan et al. 2015). Using this approach, caregivers could actively map positive experiences and resources for caregiving in all phases of disaster, with a specific focus on lesser addressed disaster phases (that is, prevention and recovery). An asset-based approach would complement the identification of facilitators, enablers, and positive experiences of informal caregiving (Morgan and Ziglio 2007). While the needs-based approach has been invaluable in identifying barriers to informal caregiving in disasters, the strength of an asset-based approach stems from its attempts to change the focus from the problems, or deficits, in a community, to the capabilities present to address the identified problems (Morgan and Ziglio 2007).

While the literature demonstrates a variety of contexts requiring informal care (for example, diabetes, intellectual and physical disabilities, and so on) and a variety of family members providing this care (for example, adult–children, parents, spouses, siblings), noticeably absent is an understanding of the issues facing children and youth as informal caregivers in disasters. According to reports from previous disasters, some children even become caregivers as a result of disasters. For example, according to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF 2007), many teenage girls were forced into caregiver roles, providing care for their siblings and older adults after the 2005 Indian Ocean tsunami. This was a result of mothers dying during the disaster, and parents leaving to provide support with disaster relief efforts. These children had to provide care for vulnerable populations during extreme contexts. There is a need for more literature to highlight the experiences, assets, and needs of this subpopulation of informal caregivers.

Based on the descriptive summary of the literature analyzed in this scoping review and knowledge gaps identified, there is a need for more research on informal caregiving in disasters. Further research is needed on facilitators of informal caregiving in disasters by using research approaches such as asset-based approaches and CBPR. More research is also needed exploring the experience of informal caregiving during the recovery phase of a disaster. To facilitate this research, studies should allow informal caregivers to be the priority population in the study, rather than care recipients, to successfully explore caregiver experiences in disasters. Studies should also investigate the experiences of children as caregivers for siblings, adults, and older adults in the face of disasters.

A limitation to this study is that the search did not capture individuals who became caregivers as a result of disaster. The caregivers included in this study were providing care prior to the disaster and continuing to provide care in disaster contexts. Additionally, using the search strategies described above, there is a possibility that literature was missed, which may have resulted in a lack of recognition of key themes or gaps. The authors used a search strategy for the indexed literature and consulted with trained librarians to build the search strategy in order to minimize the possibility of missing literature. Finally, this review did not include assessment of the quality of research studies included in the analysis.

5 Conclusion

Informal caregivers are an under-researched population in the field of disaster risk reduction, and yet they are essential to the provision of healthcare services. The purpose of this study was to explore informal caregiving across phases of disaster to understand the experience of caregivers and their families. Using a scoping review approach, this study identified five themes spanning all disaster phases. The identification of themes and related knowledge gaps represents a starting point from which to identify research priorities and inform further generation of practice-oriented research to advance knowledge on informal caregiving in disasters. Recommended areas of strategic action include pre-disaster education and training on DRR using formal healthcare services as education providers; as well as a focus on the use of qualitative CBPR research and use of an asset-based lens to explore facilitators of informal caregiving in all phases of disaster. Policymakers are aware that informal caregivers have an important role in maintaining the health and well-being of care recipients. Ensuring the well-being of caregivers in a disaster is critical to maintain this crucial support for care recipients, as well as supporting formal essential services that can become tapped out in large scale disasters. By understanding and mobilizing assets to support the resilience of informal caregivers, this will also support the resilience of the greater healthcare system and the community in disaster contexts.

References

Adams, V., S.R. Kaufman, T. van Hattum, and S. Moody. 2011. Aging disaster: Mortality, vulnerability, and long-term recovery among Katrina survivors. Medical Anthropology 30(3): 247–270.

Ahmadi, S., H. Khankeh, R. Sahaf, A. Dalvandi, S.A. Hosseini, and F. Alipour. 2018a. How did older adults respond to challenges after an earthquake? Results from a qualitative study in Iran. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 77: 189–195.

Ahmadi, S., H. Khankeh, R. Sahaf, A. Dalvandi, and S.A. Hosseini. 2018b. Daily life challenges in an earthquake disaster situation in older adults: A qualitative study in Iran. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 12(4): IC8–12.

Allweiss, P., and A. Albright. 2011. Diabetes, disasters and decisions. Diabetes Management 1(4): 369–377.

Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1): 19–32.

Armstrong, R., B.J. Hall, J. Doyle, and E. Waters. 2011. Cochrane update. “Scoping the scope” of a Cochrane review. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England) 33(1): 147–150.

Baker, M.D., L.R. Baker, and L.A. Flagg. 2012. Preparing families of children with special health care needs for disasters: An education intervention. Social Work in Health Care 51(5): 417–429.

Chandra, A., M. Williams, A. Plough, A. Stayton, K.B. Wells, M. Horta, and J. Tang. 2013. Getting actionable about community resilience: The Los Angeles County community disaster resilience project. The American Journal of Public Health 103(7): 1181–1189.

Christensen, J.J., and H. Castaneda. 2014. Danger and dementia: Caregiver experiences and shifting social roles during a highly active hurricane season. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 57(8): 825–844.

Christensen, J.J., E.D. Richey, and H. Castaneda. 2013. Seeking safety: Predictors of hurricane evacuation of community-dwelling families affected by Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder in South Florida. Journal of Alzheimer 28(7): 682–692.

Dixon-Woods, M., S. Bonas, A. Booth, D.R. Jones, T. Miller, A.J. Sutton, R.L. Shaw, J.A. Smith, and B. Young. 2006. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research 6(1): 27–44.

Durrani, S., J. Contreras, S. Mallaiah, L. Cohen, and K. Milbury. 2019. The effects of Yoga in helping cancer patients and caregivers manage the stress of a natural disaster: A brief report on Hurricane Harvey. Integrative Cancer Therapies 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735419866923.

Fast, J. 2015. Caregiving for older adults with disabilities: Present costs, future challenges. Quebec Canada: Institute for Research on Public Policy Study.

Gibson, A., J. Walsh, and L.M. Brown 2018. A perfect storm: Challenges encountered by family caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease during natural disasters. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 61(7): 775–789.

Government of Canada. 2016. Get an emergency kit! 2016. https://www.getprepared.gc.ca/cnt/kts/bsc-kt-en.aspx. Accessed 23 Oct 2019.

Grant, K.R., C. Amaratunga, P. Armstrong, M. Boscoe, A. Pederson, and K. Willson (eds.). 2004. Caring for/caring about: Women, home care and unpaid caregiving. Health Care in Canada Series. Canada: Garamond Press Ltd.

Green, S.E. 2006. “Enough already”! Caregiving and disaster preparedness – Two faces of anticipatory loss. Journal of Loss & Trauma 11(2): 201–214.

Hawe, P., and L. Potvin. 2009. What is population health intervention research? Canadian Journal of Public Health 100(1): I8–14.

Heppenstall, C.P., T.J. Wilkinson, H.C. Hanger, M.R. Dhanak, and S. Keeling. 2013. Impacts of the emergency mass evacuation of the elderly from residential care facilities after the 2011 Christchurch Earthquake. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 7(4): 419–423.

Hollander, M., and N. Chappell. 2002. Final report of the national evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of home care. A report prepared for the Health Transition Fund, Health Canada. Victoria, Canada: Centre on Aging, University of Victoria.

Kyota, K., K. Tsukasaki, and T. Itatani. 2018. Disaster preparedness among families of older adults taking oral medications. Home Health Care Services Quarterly 37(4): 325–335.

Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K.K. O’Brien. 2010. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 5: 69–77.

Mace, S.E., and C.J. Doyle. 2017. Patients with access and functional needs in a disaster. Southern Medical Journal 110(8): 509–515.

Morgan, A., and E. Ziglio. 2007. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model. Promotion & Education 14(2): 17–22.

Oliva, N.L., B. Wexler, G. Gullickson, M. Manco, A. Layton, S. McLean, and S.R. Brunskill. 2013. Disaster preparedness for veterans with dementia and their caregivers: Evolution of an educational intervention. Federal Practitioner 30(7): 29–34.

O’Sullivan, T.L. 2009. Support for families coping with stroke or dementia: Special considerations for emergency management. Radiation Protection Dosimetry 134(3–4): 197–201.

O’Sullivan, T.L., W. Corneil, C.E. Kuziemsky, and D. Toal‐Sullivan. 2015. Use of the structured interview matrix to enhance community resilience through collaboration and inclusive engagement. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 32(6): 616–628.

O’Sullivan, T.L., C. Fahim, and E. Gagnon. 2018. Asset literacy following stroke: Implications for disaster resilience. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 12(3): 312–320.

O’Sullivan, T., A. Ghazzawi, A. Stanek, and L. Lemyre. 2012. “We don’t have a back-up plan”: An exploration of family contingency planning for emergencies following stroke. Social Work in Health Care 51(6): 531–551.

Ozaki, A., M. Tsubokura, C. Leppold, T. Sawano, M. Tsukada, T. Nemoto, K. Kosugi, Y. Nishikawa, et al. 2017. The importance of family caregiving to achieving palliative care at home: A case report of end-of-life breast cancer in an area struck by the 2011 Fukushima nuclear crisis. Medicine 96(46): Article e8721.

Patton-Levine, J.K., J.R. Vest, and A.M. Valadez. 2007. Caregivers and families in medical special needs shelters: An experience during Hurricane Rita. Journal of Disaster Medicine 2(2): 81–86.

Peek, L.A., and A. Fothergill. 2008. Displacement, gender, and the challenges of parenting after Hurricane Katrina. National Women’s Studies Association Journal 20(3): 69–105.

Peters, D.J., C.M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. Mcinerney, D. Parker, and C.B. Soares. 2015. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13(3): 141–146.

Public Health Agency of Canada. 2012. What is the population health approach? http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/approach-approche/index-eng.php. Accessed 24 Oct 2019.

Romanow, R.J. 2002. Building on values: The future of health care in Canada. Final report. Ottawa, Canada: The Royal Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/english/care/romanow/hcc0023.html. Accessed 25 Oct 2019.

Sakashita, K., W.J. Matthews, and L.G. Yamamoto. 2013. Disaster preparedness for technology and electricity-dependent children and youth with special health care needs. Clinical Pediatrics 52(6): 549–556.

Schulz, R., and J. Eden (eds.). 2016. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: Academies Press.

Sinha, S.K., B. Griffin, T. Ringer, C. Reppas-Rindlisbacher, E. Stewart, I. Wong, S. Callan, and G. Anderson. 2016. An evidence-informed national seniors strategy for Canada, 2nd edn. Toronto, ON: Alliance for a National Seniors Strategy.

Skinner, M.W., N.M. Yantzi, and M.W. Rosenberg. 2009. Neither rain nor hail nor sleet nor snow: Provider perspectives on the challenges of weather for home and community care. Social Science & Medicine 68(4): 682–688.

Stall, N. 2019. We should care more about caregivers. Canadian Medical Association Journal 191(9): E245–E246.

Tricco, A.C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, M. Kastner, D. Levac, C. Ng, et al. 2016. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 16(1): 1–10.

Turcotte, M. 2013. Family caregiving: What are the consequences? Insights on Canadian society. Statistics Canada. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11858-eng.pdf. Accessed 26 Oct 2019.

UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2015. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. http://www.unisdr.org/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct 2019.

UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund). 2007. The participation of children and young people in emergencies: A guide for relief agencies, based largely on experiences in the Asian tsunami response. https://www.unicef.org/eapro/the_participation_of_children_and_young_people_in_emergencies.pdf. Accessed 28 Oct 2019.

Wakui, T., E.M. Agree, T. Saito, and I. Kai. 2017. Disaster preparedness among older Japanese adults with long-term care needs and their family caregivers. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 11(1): 31–38.

White, B. 2006. Disaster relief for deaf persons: Lessons from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Review of Disability Studies 2(3): 49–56.

Wyte-Lake, T., M. Claver, S. Tubbesing, D. Davis, and A. Dobalian. 2019. Development of a home health patient assessment tool for disaster planning. Gerontology 65(4): 353–361.

Young, T.K. 2005. Population health: Concepts and methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zuurmond, M., V. Nyapera, V. Mwenda, J. Kisia, H. Rono, and J. Palmer. 2016. Childhood disability in Turkana, Kenya: Understanding how carers cope in a complex humanitarian setting. African Journal of Disability 5(1): Article 277.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following librarians at the University of Ottawa for their guidance throughout the project: Mish Boutet, Lindsey Sikora, Sarah Visintini, and Marie-Cécile Domecq. Thank you for your unending patience and library sciences wisdom. Thank you to Lyric Oblin-Moses for your help refining the search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria by screening 5% of the articles pulled from the initial Medline search. This research was partially funded by the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation through the Early Researcher Award, awarded to Dr. Tracey O’Sullivan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pickering, C.J., Dancey, M., Paik, K. et al. Informal Caregiving and Disaster Risk Reduction: A Scoping Review. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 12, 169–187 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-021-00328-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-021-00328-8