Daily living is a lot of work—and the world relies on the unpaid labor of women to keep households functional. Women spend an average three to six hours per day on cooking, cleaning, watching over small children and ailing relatives, and any number of other domestic tasks, compared to men’s average of anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours.

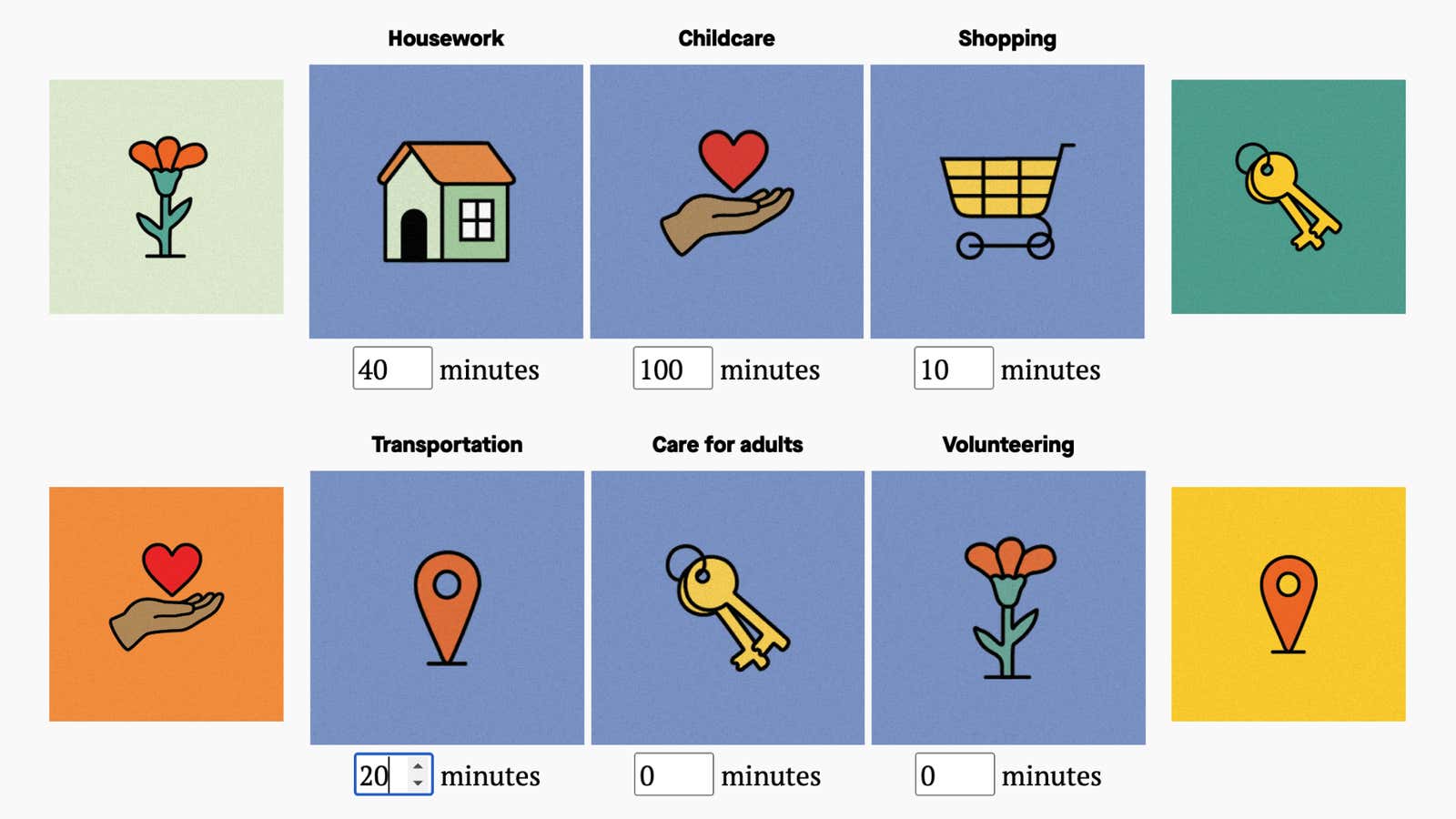

How many minutes of each type of labor do you do each day?

Overall, the unpaid labor of women and girls around the world contributes an estimated $10.8 trillion to the global economy each year, according to a January 2020 report from Oxfam.

The pandemic only further underscored both the profound gender gap in the division of domestic labor, and just how necessary that work is. “This is incredibly valuable labor to society,” says Kristen Ghodsee, a University of Pennsylvania ethnographer who specializes in gender studies. “Primary parents are raising the next generation of taxpayers and consumers and workers, and they’re doing it for free.”

Given how much everyone benefits from women’s unpaid labor, could compensating people for tasks like housework and child care bring about a more just—not to mention wealthier—society? Quartz spoke with economists to better understand the case for compensating people for unpaid labor.

The unequal burden of unpaid labor

While women consistently take on more domestic labor than men around the world, in nations with strong social services, they tend to spend less time doing it. Scandinavian countries like Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, as well as other European countries and places like New Zealand and Canada, all offer some form of universal childcare as well as socialized medical services that pay for professional nurses to make home visits to care for children and elders. “Any time you have the social provision of certain kinds of care work, which is being done by the state or the municipality, it’s going to reduce the burden of unpaid care on women in the family,” says Ghodsee.

It helps that in many of those places, men do a bigger share of unpaid labor, too.

The data also show that even in wealthy countries, the distribution of labor is still very uneven. In Korea, for example, women spend less time doing unpaid labor than in most other countries. But they take the lion’s share of what there is to do. Korean men only do 18.6% of the work.

Most people who care about gender equality agree that the uneven distribution of household labor is a problem—not only because of the stress that comes with working the “double shift,” but because the imbalance may prevent women from realizing their full professional and economic potential. At the same time, they worry about the potential repercussions of providing compensation for household tasks.

Is the world ready to pay for unpaid labor?

Some economists warn that paying women for household work could wind up encouraging them to drop out of the labor force. A 2021 study by economist Yulya Truskinovsky, published in the Journal of Human Resources, supports this concern. The study looked at the outcomes of US state programs that allowed low-income families to use subsidies to pay relatives (typically grandmothers) for watching children. It found that the subsidies didn’t greatly increase the likelihood that grandmothers would start providing child care if they didn’t already. But the extra income did encourage grandmothers who had previously held down jobs as well as cared for their grandchildren to cut back on work.

On the one hand, this might be a change worth celebrating—why shouldn’t overstretched grandmothers work less? But from a financial perspective, Truskinovsky says, there are drawbacks. If the grandmothers are working less, they may not be receiving health insurance or other benefits. They’ll presumably save less money and reduce the size of their Social Security payouts later on.

“Often, we think we prefer to have a family member take care of [relatives] rather than a stranger or a professional. But at the same time, compensating people for providing care is pulling them out of the formal labor market,” says Truskinovsky, an assistant professor of economics at Wayne State University. “If we don’t kind of design compensation in a way that mimics the formal labor market, then I think there are a lot of costs.”

Would compensating unpaid labor be bad for gender equality?

A related fear is that offering compensation for unpaid labor could wind up reinforcing conventional gender roles, diminishing women’s presence in the labor market. “That’s not necessarily desirable either from a society perspective or from an equality perspective,” says Anne Boring, an economist at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

History shows that sexism can indeed undergird seemingly generous policies. In the socialist Eastern Germany during the second half of the 20th century, Ghodsee says, women received a range of benefits—from a year’s worth of paid maternity leave to one day off a month to take care of domestic tasks. On one hand, such policies recognized the reality that most women were performing the majority of domestic work in their households. But from a gender-equality perspective, Ghodsee says, “American feminists always disliked these policies as they also dislike things like maternity leave [as opposed to the broader parental leave], because it emphasizes that this work should be done by women.”

Of course, it’s possible that if housework and child care received compensation, then those activities might become less associated with gender, and men would be more willing to take them on. But given that men still earn more than women, that might be too optimistic an expectation. “As long as there is a gender pay gap, it still makes more sense for women to be the ones who slow down their careers and start taking more care of the kids,” says Boring. Indeed, during the height of the pandemic, many families were forced to make that very calculation, with women cutting back on work in order to take care of kids who could no longer go to daycare or school.

How much is unpaid labor worth?

Figuring out how much unpaid labor is worth is also a complicated task. According to neoclassical economics, wages for different types of jobs typically reflect the marginal productivity of workers—that is, companies pay employees based on the amount of money their contributions generate for the employer.

But Boring says that wages for care and domestic work are often low for a different reason—because those tasks have historically been performed largely by women. It’s a phenomenon that also shows up in the wages of nurses, teachers, and other “care work” professions.

Boring also notes that the value of care work is very subjective. “A private nanny could be very well-compensated,” she says. And from a practical standpoint, it would be difficult to assign an hourly wage system to private activities that happen inside the home and can vary widely in both nature and execution. “I don’t want to pay somebody the same wage for cooking a gourmet meal that I pay them for breastfeeding an infant, where one has huge health and care and social implications and one is kind of a hobby,” says Nancy Folbre, professor emerita of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, whose research focuses on unpaid care work.

Given all these complications, experts tend to favor the idea of providing compensation for unpaid work via routes other than direct wages, such as child allowances and tax credits. These have the added advantage of being less controversial than providing direct wages for housework, and thereby more likely to receive support from voters and politicians.

“Many of us would want our tax dollars to go to lifting children out of poverty,” says Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University,. “We have a lot of work that shows that if you lift children out of poverty, then as adults, they’re they’re not poor, and they’re taxpaying citizens.”

The pandemic provided ample evidence of that. Using an expanded child tax credit program, the US provided monthly cash payments (typically $250 or $300 per month) to low-income families in 2021. This program wasn’t aimed directly at compensating parents for unpaid labor. But in practice, the government policy still put more money in families’ pockets. Over six months in 2021, researchers found that the payments slashed child poverty in the US by 30%. Such findings help make the case that government payments for caregivers are beneficial not just for parents and children, but for society at large.

Paying for childcare instead of paying caregivers

Another option is to provide more social services, like universal child care, that would give women greater opportunities to participated in the workforce.

There is evidence that this approach works. Writing in a 2018 report commissioned by the International Development Research Center, Folbre describes options including Chile’s Crece Contigo program—which provides government-funded daycare centers home care for young children—and Mexico’s Estancias program, which pays for up to 90% of day-care costs. “Among women benefiting from the [Estancias] program, 18% more are now employed, working on average six additional hours each week,” Folbre notes.

Whether governments provide some form of compensation for unpaid labor or offer affordable social services, economists say the goal should be to give women more control over how they spend their time.

Not every country can be Sweden—but every country can take steps to give women the freedom to choose whether they perform the bulk of their labor inside or outside the home. Says Truskinovsky: “I think that we should always be striving to give people options.”