Mental illnesses tend to defy formulaic explanations. Is depression the result of chemical changes in the brain? Is it a byproduct of physical illness, childhood trauma, or all of the above?

This slipperiness is what makes coping with mental illness such a frustrating experience. If only we could understand exactly why we feel shitty, we’d feel less shitty.

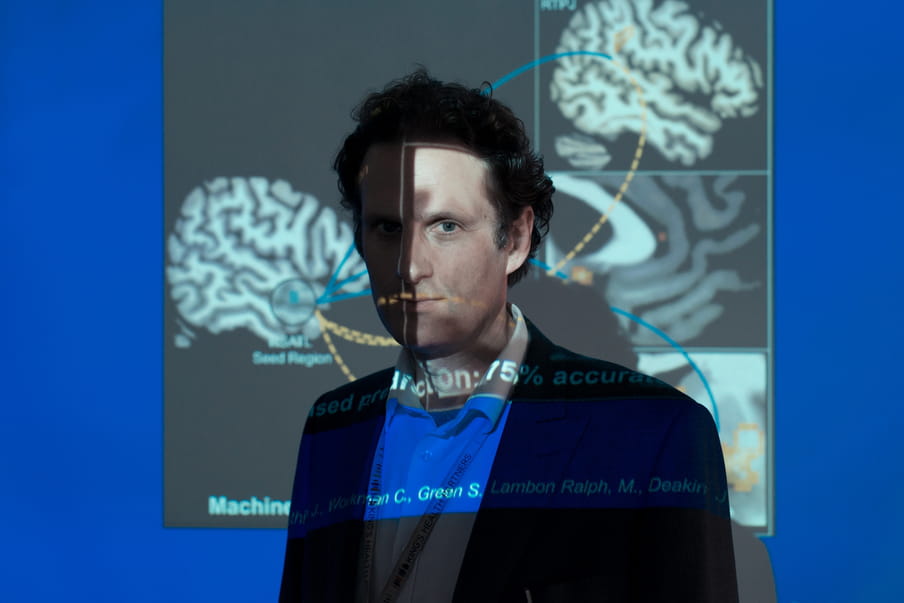

From his laboratory at King’s College London, Roland Zahn is trying to help. Zahn has been researching brain activity associated with mood disorders, focusing on one piece of the puzzle: why do many people with depression report feeling excessive guilt or self-blame?

In 2012, when he was with the University of Manchester, Zahn and his colleagues used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of two groups of people. One group included people who were in remission from major depression for more than a year, while the control group had people with no history of depression. Both groups were asked to imagine behaving badly – for example, being "stingy" or "bossy" towards their best friends.

It was the first time neuroscientists had found evidence confirming the close relationship between depression and guilt – the handiwork of the "superego" – that is central to the work of Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis.

Patients with depression can be overwhelmed by guilt even when it makes no logical sense. In psychology parlance, this is overgeneralised guilt. While the science is very new and still evolving, Zahn and his fellow researchers believe this overgeneralised guilt could be the result of altered connectivity between the upper part of the right anterior temporal lobe of the brain, associated with the knowledge of social behaviour, and the subgenual region, which is thought to store information about "social agency" – in other words, understanding who is responsible when something goes wrong socially. (The exact function of the subgenual region is disputed.)

"People with depression can struggle to understand exactly what is inappropriate about their behaviour when feeling guilty, thereby extending guilt to things they are not responsible for and feeling guilty for everything," Zahn says. "It is likely that a network of brain regions is necessary to guard against overgeneralisation, and that there are individual differences regarding which parts of this network are most important for whom."

The communication between specific parts of the brain is measured in terms of functional connectivity, Zahn explains. "If the signals [between two brain regions] go up simultaneously, we think it might be a sign that the regions are somehow talking to each other," he says. "These measures of functional connectivity are different in people with depression. And the interesting thing is, they are altered in a specific way for guilt, compared with anger."

Can we train the brain to treat depression?

Zahn believes his research could help predict how vulnerable you are to relapsing into depression after a period of remission.

"We tried to distinguish people who might have another episode in the next year from those who are likely to stay stable and were able to show that self-blame-related connectivity in the brain is predictive of recurrence risk," he says. "We are currently working on individual prediction models which use imaging and cognitive measures of self-blaming biases."

What is most exciting about Zahn’s current work is its attempt to understand if a technique called "fMRI neurofeedback" can be used to train the brain and change the way the brain regions communicate with each other, while, as Zahn describes it, "they are memorising guilt and anger". The findings could provide proof-of-concept for a novel treatment option for patients of depression.

There is, however, a caveat. The technique may not work for people who also report anxious distress. "These people are more likely to have intact defence mechanisms. If someone criticises them and their self-esteem is threatened, they are likely to feel anger, as opposed to those suffering from the classical, melancholic form of depression," says Zahn.

"It’s still early days, but we need to better understand what brain regions are actually underpinning the self-blame that some people with anxious depression are feeling. I think the brain connectivity patterns must look different."

And what about cultural differences? Do they also play a role in how different people experience guilt? "There is always discussion about the frequency of guilt in depression in different cultures," he answers. "But you can’t really compare them because the healthcare settings are so different. I am not convinced that the transcultural differences are very clear. People have this idea, for example, that Catholics feel greater guilt than others. It’s a nice idea, but I think it’s nonsense."

The unhelpful split between psychology and biology

Zahn’s work at the intersection of brain science and abstract psychological concepts, such as guilt and self-blame, addresses a frequent attack against psychiatry: that it fails to take a holistic view of mental illness and places too much emphasis on treatments (read: pills) backed by not enough evidence.

Philip Hickey, a retired American psychologist who runs the platform Mad in America, writes in a sharp critique of pill-based psychiatry: "‘Why am I depressed?’ ‘Because you have such and such wrong in your brain.’ But despite four decades of extremely motivated and well-funded research, these brain illnesses have not been identified or described."

Zahn’s work to shed light on brain processes is important in this context. He also bemoans "the unhelpful split between psychological and biological approaches" and claims one of the reasons for the split is that most of us – especially those who have never experienced mental illness – are afraid to admit that the biology of our brain could in part control our mental state, and that we are not fully in control of that.

"I think we need to develop a better culture of debate which is based on rigorous fact-checking. If you did that, I am sure you would find that the evidence base for treatments in psychiatry is not inferior to other fields," he says.

What is the one thing about the brain that we’d do well to remember? “The brain constantly changes. Every psychological change and any learning experience is reflected in our brain, so the idea that there are brain correlates of mood disorders [which parts of the brain correspond to specific disorders like depression] does not mean these cannot be changed,” says Zahn, before adding: “We are only at the very beginning of understanding this, so everything you read should be taken with some caution.”

![Wallpaper on a wall with a quote by Henry Maudsley saying "...to promote exact scientific research into the causes and pathology of insanity with the hope that much may yet be done for its even [a few words are not readable due to a pole blocking the view] successful treatment". A plant and some flyers in a rack are standing next of it.](https://archive.cdn-thecorrespondent.com/image/9O75z6kDuVselZnjNi9MOaNLD3Q=/904x603/9c13ff80530748a3814b0a245d680842.jpg)

Dig deeper

Can guilt and shame ever be positive?

Few emotions are as inseparably fused with what it means to be human. We need to understand both better.

Can guilt and shame ever be positive?

Few emotions are as inseparably fused with what it means to be human. We need to understand both better.