Mysteries Of The Superstition Mountains

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Everyone loves a treasure hunt. Very few things are more exciting than the prospect of rolling up your sleeves like Indiana Jones or Scrooge McDuck and uncovering a long-hidden hoard of gold and making the cover of all the papers. But how far would you go for fortune and glory? Would you climb into a hellmouth?

The Superstition Mountains are a mountain range east of Phoenix and are known for their picturesque volcanic peaks and jagged canyons. But they're even better known for something else: the legendary Lost Dutchman's Mine, a much-ballyhooed secret stash of wealth sought by daring adventurers known as "Dutch hunters." But George Johnston, president emeritus of the Superstition Mountain Museum, claims that more hikers disappear in the Superstitions than any other mountain range, with an average of four or five hikers disappearing or dying there annually.

This could be due to the range's sheer drop-offs, deep canyons, wild swings in temperature, or unfriendly wildlife. Or it could be related to the strange sounds, mysterious disappearances, and unexplained deaths that led to the feeling of superstition that gave the range its name. Join us as we peer into the hellmouth and search for the truth of the Lost Dutchman's Mine and other mysteries of the Superstition Mountains.

Apaches and Peraltas

As is true of nearly any sufficiently old and popular legend, there are many variations on the tale of the Lost Dutchman's Mine, but most complete versions start with the Peralta family. According to AZ Central, the Peraltas were a wealthy Mexican family led by patriarch Don Miguel Peralta, who operated several mines in the area of the Superstition Mountains. In contrast, writer Jen Wolfe says the Peraltas were cattle ranchers. At any rate, tales agree the Peraltas somehow came across a large deposit of gold in the Superstition Mountains. That's the good news. The bad news is that they all died. (Almost all.)

Again, there are plenty of versions of the story, but the key detail is that a group of Apaches killed all the Peraltas but one. Maybe it was because they didn't like the way the miners were treating land sacred to them, maybe they wanted the gold for themselves, maybe they felt possessive about the mine and its treasures, or maybe it was just one of those run-of-the-mill, no-reason massacres that white people think happened all the time apparently. At any rate, the Peralta Massacre is a major element of the story and commemorated by place names such as Massacre Falls. In one version of the story, it was a different family who was killed while the Peraltas made off with a fortune while hiding all trace of their mine, like jerks.

Doctor Thorne

The story doesn't end here, of course, as you might have gathered by the fact that we haven't gotten to a Dutchman yet. (Spoiler: there is never a Dutchman.) The next player in the tale is one Doctor Abraham Thorne, who, like the Peraltas, is not Dutch. According to the Lost Dutchman Days website, Thorne was a doctor from Illinois who wanted nothing more than to travel west and practice medicine among Native American tribes in the Southwest. When President Lincoln created a reservation for the Apache along the Verde River, Thorne got his chance.

Thorne would spend years living among the Apache, tending to their sick and wounded, and garnering respect from tribal leaders. In 1870, in order to repay his kindness, elders of the tribe promised they would take Thorne to a place with lots of gold. Their one strange yet convenient condition was that Thorne had to be blindfolded when they took him to the gold. With his eyes covered, Thorne was taken on a journey of about 20 miles. When the blindfold was removed, he saw a sharp pinnacle of rock, generally interpreted to be Weaver's Needle (pictured above), the most notable landmark of the Superstitions. In front of him, he saw a huge pile of gold nuggets against the canyon wall (you know, like mines have). He gathered up as much as his non-Dutch arms could carry and later sold the nuggets for $6,000, presumably in 1870 dollars.

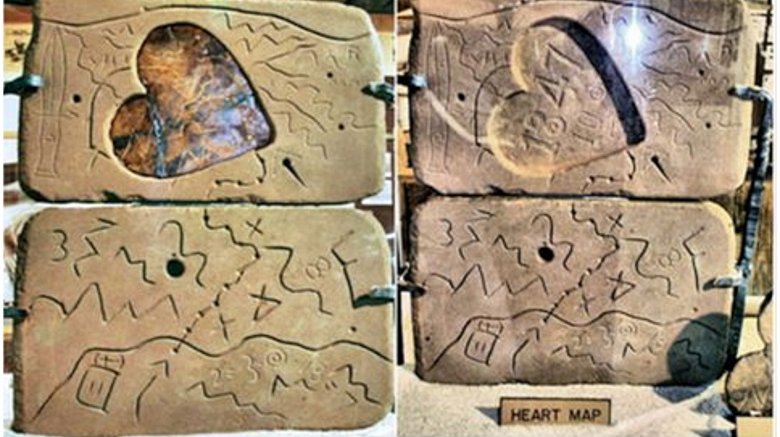

Peralta Stones

There's still a lot of story to go; we might as well get real weird with it. How do you find a treasure? With a treasure map, of course. But a treasure as shrouded in mystery and notoriety as the Lost Dutchman's Mine can have no ordinary map such as you might find on a spinner rack at a gas station or by asking Siri to direct you to the ancient and mysterious Apache gold cache.

Nope. The secret of the Dutchman is allegedly laid out in the Peralta Stones, a series of etched stones — some rectangular, some shaped like crosses, others like hearts — that allegedly indicate the location of the vast riches of the Superstitions, if only you can read them right. The various stones have been named the Trail Maps, the Priest Map, the Horse Map (featuring a horse drawn with a disturbingly succulent butt), the Stone Crosses, and the Heart Map. The Heart Map features not one but two pop-out hearts, including the so-called Latin Heart, which bears a number of inscriptions in not entirely accurate Latin.

According to author Jim Hatt, these stones were found in the 1940s on the side of the road by a police officer named Travis Tumlinson, but the names "Pedro" and "Miguel" on the stones stands as evidence that these weird coded maps belonged to the Peralta family (hence the name) and the stones were spilled on the roadside during the Apache Massacre. Hatt goes on to do some truly Art Bell-level interpretive work on the Latin heart.

The Lost Dutchman

Finally, the Dutchman comes in. Well, sort of. Like we said, there's no Dutchman, at least in the sense that there's no one from the Netherlands in this story. There is a Germanman, let's call it. The Dutchman terminology comes from the same mix-up of the words "Deutsch" (German for "German") and "Dutch" (English for "Dutch") that gives us such terms as "Pennsylvania Dutch."

The Germanman in question is one Jacob Waltz (various spellings of his name abound), though a second Germanman with a suspiciously similar name, Jacob Weiser, is often included in the tale. In a version of the story related by True West magazine, Waltz and Weiser were prospectors who hadn't yet found their big score until one night they saved a man's life in a cantina brawl. That man turned out to be (wait for it) Don Miguel Peralta, who, in gratitude, told the two men the location of his family's bountiful mine in the Superstition Mountains.

Weiser disappeared under mysterious circumstances — in some versions killed by Apaches, in others killed by Waltz — but Waltz would return to the mine whenever he needed money and then pop back into town, making it rain (hail?) gold nuggets, reportedly of the richest ore anyone had ever seen. Waltz allegedly died of pneumonia in the winter of 1891 with a sack of gold under his bed. Since that moment, the search for the Lost Dutchman's Mine has been on.

The Dutchman's legend spreads

The story of the Dutchman and his unimaginable bounty would soon catch the public imagination and become one of the best known and most sought-after treasures in American history. During the mid-20th century, when Westerns were especially popular, the tale of the Lost Dutchman's Mine was a popular motif.

The 1945 book Thunder God's Gold by Barry Storm tells of the author's real-life attempts to find the gold mine himself during the 1930s and 1940s. This book inspired the 1949 movie Lust for Gold, which starred Glenn Ford as Jacob Walz and Ida Lupino as (whitewashed) Julia Thomas, Walz's neighbor who took care of him on his deathbed and who was allegedly the one person he told the location of his mine. (She couldn't find it either.)

Likewise, the mine found its way onto TV, such as in a 1961 episode of the Western series Laramie, and more improbably, a 13-episode serialized story on the Hanna-Barbera cartoon Ruff and Reddy. Legendary artist Jean Giraud drew his Western hero Lieutenant Blueberry hunting the mine in La mine de l'Allemand perdu, and equally legendary Duck artist Don Rosa had Scrooge McDuck sniffing out that gold in The Dutchman's Secret.

The mine and its secrets have similarly inspired video games and amusement park rides, and even the park service got in on that sweet Dutch action, opening the Lost Dutchman State Park in 1977, which includes trails named for figures in the legend, like Jacob Walz and the Peralta family.

Death of Adolph Ruth

Much of what we've discussed here is pretty deep into legend territory, even though there really was a Jacob Walz/Waltz whose grave you can really visit and there really was a Julia Thomas, as True West magazine will attest. But the event that really spurred interest in the Lost Dutchman's Mine, before the movies, before Barry Storm, was the real-life disappearance and death of treasure hunter Adolph Ruth.

According to AZ Central, Ruth was "a 66-year-old veterinarian employed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Animal Husbandry, who had a longstanding obsession for locating the fabled Lost Dutchman Mine." When he acquired a number of maps to old mines, Ruth became something of an amateur treasure hunter, and in an attempt to find a mine in California, had fallen down a ravine, permanently injuring one of his legs.

By 1931, Ruth became convinced that one of the crudely drawn maps in his possession would lead him to the Dutchman's mine, but his luck wasn't any better than it had been in California. Within days, Ruth had disappeared without a trace. It wasn't until later that campers discovered a note in a bottle written by Ruth saying that he had (again) broken his leg and needed help. But perhaps of more interest was the note's casual postscript: "P.S. Have found the lost Dutchman."

When Ruth's body was found in a gold-lust-fueled search in December 1932, the mystery only deepened.

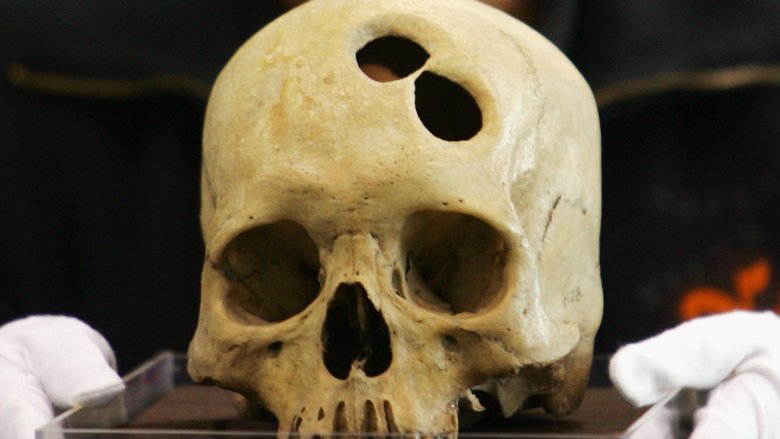

Ruth's death gets weirder

Although Ruth's note concerning his broken leg and need for help led searchers to believe that he must have starved to death waiting for rescue, as AZ Central reports, new theories popped up after the discovery of his skull with a hole in it that according to the coroner's reports was created by an "Army-style 44 caliber revolver." The most common suggestion, of course, was that Ruth was killed for his maps by someone else familiar with the legend of the Dutchman's mine, though officials suggested suicide was more likely. But in Thunder God's Gold, Barry Storm alleges that on his own search for the mine, he had barely escaped the fire of a sniper he called "Mr. X" who he believed was protecting the mine. He suggests that Adolph Ruth may have also gotten too close and fallen prey to this mysterious sniper (who apparently uses a revolver instead of, say, a rifle).

Wait, it gets weirder. A month after the discovery of Ruth's skull, the rest of his remains were found almost a mile away, confirmed by the presence of the steel plate in his leg from his previous treasure hunt heck-up. Among the relics of his body was a checkbook, in which he had been writing daily notes of his adventures. In this book was a description that modern Dutch hunters believe proves he found the mine, which was punctuated with Julius Caesar's classic dunk on King Pharnaces II: "Veni, vidi, vici." I came, I saw, I conquered.

Other disappearances

If you know anything about human nature, you know Ruth's disappearance and mysterious death did not dissuade others from following in his footsteps, and, in fact, the headlines brought on by his story only inspired thousands of imitators.

Author Tom Kollenborn reports that a prospector by the name of James A. Cravey thought he could beat the odds of finding the mine by using a helicopter in 1947. His headless body was found months later, tied up in a blanket with his skull 30 feet away. The coroner reported "no evidence of foul play."

The Phoenix New Times relays the story of Jesse Capen, a 35-year-old Denver resident who disappeared searching for the mine in 2009. AZ Central reports on the bodies of three more men found in 2011 who had been lost in 2010 while seeking the mine, one of whom had been lost and rescued the year before in the same search.

As George Johnston from the Superstition Mountains Museum suggests, there are a great number of tragedies linked to the Superstition wilderness, and the Prairie Ghosts website lists a large number of disappearances and deaths in the area surrounding the mountain and mine over the last century, though some of those may be as legendary as the mine itself, so take them with a grain of salt, even if (i.e., especially since) a shocking number of them involve headless bodies and mysterious gunshots.

Gate to Hell

Why is there so much death and disaster surrounding this beautiful stretch of American land? Is it because foolhardy adventurers travel ill-prepared into an area they don't understand looking passionately and in vain for something that doesn't exist? No, of course not. Obviously it is because the mountain is a hellmouth.

As Jen Wolfe reports, many people in the area believe the Superstition Mountains were sacred to the local Native Americans, who believed it to be the home of the Thunder God, who housed a great treasure there that he would protect at all costs. Tom Kollenborn's explanation of the types of summer storms common in Apache Junction makes the connection between the mountain and a god of thunder clear and believable.

But that's not all. As the Occult Museum suggests, some believe there's a hole at the top of the mountain that leads clear through to the underworld, and it is from this hole that all the winds of the world issue forth. There are reports of strange voices and shadows that emerge from the area, as well as various tales of sightings of aliens and lizard people, but you can Google that nonsense yourself. The point is that people have some strange ideas about the place and all the death and mystery surrounding it.

Some truth revealed

So, is there gold in them thar hills? Should you load up a backpack with Slim Jims and novelty colored Mountain Dews in an attempt to uncover gold that has variously belonged to a non-Dutch Dutchman, a blindfolded doctor, a Mexican mining family, a tribe of Apaches, the Thunder God himself, and some soldiers we didn't have room to mention before? Well, no. Almost certainly not.

Tom Kollenborn, who is by far the most prolific author on the Superstition Mountains and its surroundings, says, "I have never found any evidence that really suggested the mine existed. Everything is based off subjective hearsay. Actual facts about the lost mine just don't exist."

If the word of the world's leading expert on the area isn't enough for you, Thinking Muse points out that the geology isn't there: the Superstitions are volcanic, and volcanic rock does not tend to have a lot of gold in it.

OK, what if, as some say, the mine isn't really a mine but rather a cache in which the Peraltas hid their vast wealth? As Skeptoid and others point out, there's no evidence that the Peraltas ever mined the Superstitions or indeed ever even lived in Arizona. The Peraltas only ever mined in California, and anything different was a contrivance of later authors looking to build up the legend.

One thing there is evidence for is that maybe the Lost Dutchman's Mine is safer left to the realm of myth.