Developing and Implementing a Global Citizenship Based Curriculum

Julkaistu: 7. syyskuuta 2022 | Kirjoittaneet: Iris Hubbard, Jenny Torroledo, Hanna-Mari Koistinen ja Ritva Kantelinen

Global citizenship education has recently become a slogan in education, but what exactly does it entail? How can we support young language learners with the intention of encouraging them to become lifelong learners and citizens of the world? This article explores the implementation of after-school club sessions, pop-up events, and drop-in class visits through the lens of global citizenship. The results and feedback from the project will hopefully inspire future development and implementation of global citizenship-based curricula at the two teacher training schools in Joensuu, Finland and wider.

What is global citizenship education and why is it important?

Educating to become an active and important member of the world has always been relevant and present throughout international and Finnish curricula. However, it is more recently that academics have tried to conceptualize this aim as global citizenship education (GCE). Global citizenship is a broad concept that includes language learning, intercultural respect, and communication (Schattle, 2007). Additionally, there have been many approaches to developing and implementing global citizenship education ranging from a soft to a more critical version (Andreotti, 2006).

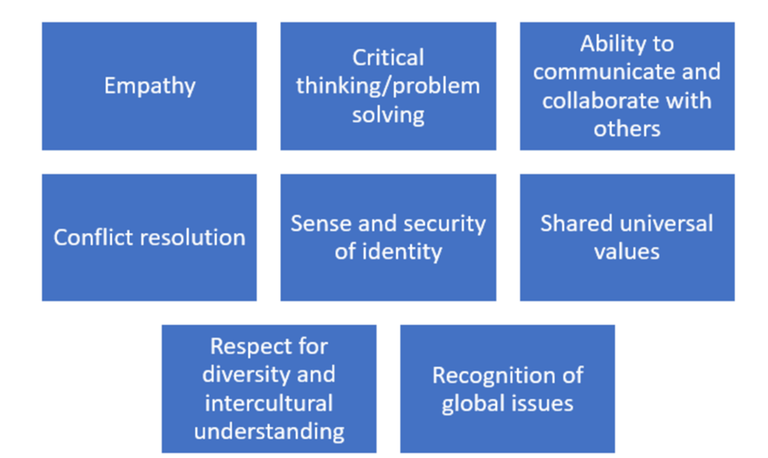

Three of the most common themes defining global citizenship found repeatedly across literature have been, “social responsibility, global competence and global civic engagement” (Morais & Ogden, 2011, p. 3). UNESCO (2015) suggested the development of curricula topics and learning objectives, along with eight competencies identified by the Global Citizenship Education Working Group (GCED-WG; Brookings Institute, 2017). These eight competencies are illustrated in the picture below.

Figure 1. Eight Global Citizenship Competencies. Reprinted from “Global Citizenship Education in Early Language Education: A comparative study of fourth-grade language curricula and students’ attitudes towards global citizenship competencies from three countries: Colombia, Finland, and the U.S.A.”, I. Hubbard and J. Torroledo, 2022. Reprinted with permission.

According to UNESCO (2015), their suggested topics and learning objectives can be used to develop the eight global citizenship competencies as they are closely related to each other. For example, they include but are not limited to taking action, levels of identity, and respect for diversity. Thus, a global citizen takes action on global issues from a local and international perspective, uses a critical approach to understand the (GCED-WG; Brookings Institute, 2017) interconnectedness of global issues, shows empathy, has the ability to communicate and collaborate with others, demonstrates the use of conflict resolution skills, has a sense and security of identity, has shared universal values (e.g., human rights, peace, and justice), and finally shows respect for diversity and intercultural understanding (GCED-WG; Brookings Institute, 2017; UNESCO, 2015).

Andreotti (2006) suggests that GCED should promote spaces for students to discuss, debate, analyze and experiment so they can learn through a more critical approach that questions the injustices and power dynamics connected to global issues. Otherwise, students could be at risk of perpetuating and reproducing “systems of beliefs and practices that harm those they want to support” when learning through a soft or surface-level GCED approach (p.7).

Moreover, the final question is how teachers can “apply the global concepts and skills in real-life contexts and analyze or clarify the global values through social/civic participation” (Brown & Kysilka, 2002 in Harshman, 2015). Therefore, this project focused on implementing global citizenship skills at the UEF teacher training schools. The project attempted to pair global citizenship education with language education as suggested by Almazova et al. (2016). We hope that our project has inspired our learners to become more open-minded and caring citizens of the world (Andreotti, 2006).

From the School-path to the Global Citizen’s Highway – Koulupolulta maailmankansalaisuuden valtatielle

The project From the School-path to the Global Citizen’s Highway started from the need to encourage GCED in students’ mindsets. The five project teachers are all international master's students at the UEF. The lessons and activities were developed based on a GCED curriculum that included the eight competencies and the topics and learning objectives previously mentioned in this article (GCED-WG; Brookings Institute, 2017; UNESCO, 2015).

The first phase of this project (Koulupolulta I, 2020-2021) concentrated on only lower comprehensive school pupils at UEF Teacher Training School, Tulliportin normaalikoulu (grades 1–6) with two project teachers, Iris Hubbard and Jenny Torroledo during the spring of 2021. The project aimed to develop a global citizenship mindset in pupils through after-school clubs and pop-up events. In phase two (Koulupolulta II), the project expanded to include three more project teachers, Balázs Hergert, Juan Antonio Pérez, and Fernanda Chavez. It broadened the perspective to higher comprehensive (grades 7–9), and upper secondary school students (grades 10-12) at Tulliportin normaalikoulu and to the other teacher training school, Rantakylän normaalikoulu (grades 1–9).

The after-school clubs, pop-up events, and class visits were designed around the UNESCO (2015) global citizenship topics and learning objectives, the eight global citizenship competencies (Brookings Institute, 2017), and the students' needs, interests, and abilities. They were implemented in the frames of the National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014 with the aim of exploring and working toward a global citizenship mentality. The project's main language of instruction was English with the addition of students' home or native languages along with the international teachers' first languages. Additionally, the use of interdisciplinary methods such as music, art, dance, science, home economics, and geography were used to promote student engagement and curiosity about global issues. Ultimately, this project aimed to develop lifelong learners who are willing to take action and remain open-minded about their roles as global citizens in our ever-growing intercultural and diverse society.

This project benefited from the participation and collaboration with English teachers Hanna-Mari Koistinen, Jasmiitta Saarikorpi, Sari Parkkinen, Katarina Liljeqvist, Elina Ukkonen, and Early Language Education for Intercultural Communication (ELEIC) professional practice students. In addition, English teachers Hanna-Mari Koistinen and Elina Ukkonen have been in charge of mentoring the project teachers and organizing timetables for the clubs and pop-up events as well as project reporting. French and Spanish teacher Noora-Liia Rautio and English teacher Hanna Hotanen have also been in charge of organizing timetables for Tulliportti higher comprehensive and upper secondary school lessons and pop-ups.

Finally, this project provided inspiration for a master’s thesis called Global Citizenship Education in Early Language Education: A comparative study of fourth-grade language curricula and students’ attitudes towards global citizenship competencies from three countries: Colombia, Finland, and the U.S.A. (Hubbard & Torroledo, 2022). The study also put the concept of global citizenship education in perspective as the project teachers challenged their preconceptions and aimed to implement a curriculum that would encourage pupils and students to think outside the box. The teachers understood that a critical version of global citizenship education was needed for students to become more thoughtful and engaged citizens of the world.

Pop-up events

During phase one (Koulupolulta I), the pop-ups targeted pupils during lunch breaks and recess periods. These events reached a smaller audience and were held inside. During the second phase (Koulupolulta II), some of the pop-ups were held outside and consisted of large-scale events that had multiple sessions or workshops for students to drop by and participate in. The pop-ups were centered around a specific theme or topic such as the European Day of Languages celebrated on September 26 every year.

For example, the English teachers and ELEIC student teachers organized activities for the European Day of Languages pop-up event held in September 2021. The day was specifically planned for comprehensive school pupils in Tulliportti and Rantakylä Teacher Training Schools. The multilingual and multicultural activities consisted of language challenges for the pupils. For example, they practiced writing their names in Japanese, learned to recognize different languages via an audio exercise created in the BookCreator application, and learned words and phrases in Italian.

In addition, this spring of 2022, informal recess breaks were organized by project teachers. Here, pupils were invited to participate in shorter outside activities that connected global citizenship topics to physical movement and games. One activity was a telephone game where one pupil started by whispering a word or phrase in another language to another pupil and it was passed down the line of pupils. The aim of the game was to see how much the word or phrase changed as it was passed between pupils while introducing them to world languages and the idea of meaningful communication.

After-school clubs

Meanwhile, the clubs were held entirely inside classrooms at each school for primary pupils. The participation of the pupils was voluntary, and each group had one session per week. The groups were divided by grade level and pupils’ needs following the initial COVID-19 restrictions; there were approximately 3 to 4 groups for every school. These sessions had an introductory/warm-up activity, followed by two main activities and a closure/wrap-up discussion or reflection (see Picture 1). The project teachers developed weekly lesson plans to implement the after-school club sessions at each school. For example, the topics connected to the eight overarching competencies included but were not limited to cultures from around the world, cultural stereotypes, global water pollution, gratitude and communication, space representation and plastic pollution, art and beauty, disabilities and senses, conflict resolution and problem-solving, food waste, indigenous people (Sámi people), and equality (women's rights).

Picture 1. In our club session Schools Around the World, students guessed and drew what the other half of the picture looked like. Then, students engaged in a discussion around privilege and school appreciation. This was an example of a main activity from the middle of the lesson.

Secondary class visits

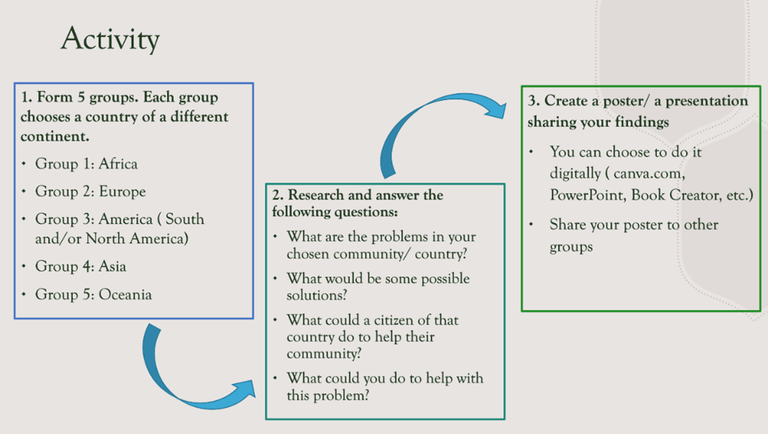

The class visits consisted of lessons held in the subject teachers’ classrooms that included topics relevant to students’ lives and connected to the eight competencies of global citizenship education (Brookings Institute, 2017). They lasted about one hour and followed the same structure as the after-school clubs. For example, the first secondary class visit introduced the concept of global citizenship to pupils. The pupils brainstormed and discussed what global citizenship means and then researched and presented possible solutions to world issues.

Picture 2. In the first class visit, students explored what it means to be a global citizen, researched some global issues, and discussed possible solutions to them.

European Language Portfolio (ELP)

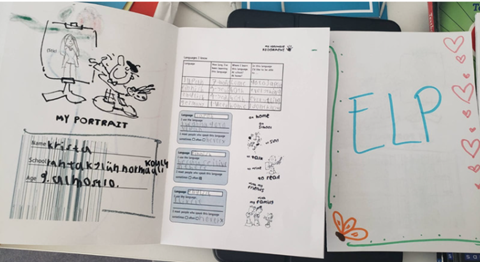

Finally, another aim of this project was to test and use the European Language Portfolio (ELP) to develop the use of language profiles in practice. For instance, exchange students and ELEIC students planned and implemented one ELP task during their Teaching Practice course for a group they taught in February 2022. Additionally, the ELP was used as a source to recognize and reflect on pupils’ language learning for primary school club sessions and secondary class pop-up visits. In those sessions and class visits, the three main components of the ELP (language passport, biography, and dossier) were introduced to the pupils, and then pupils reflected on their language journeys thus far. These sessions were also paired with topics related to language oppression and preservation and the importance of lifelong language learning.

Picture 3. Pupil examples of the paper ELP from the after-school club sessions.

Where to go from here?

From our experience with this project and thesis research, a softer approach to global citizenship is a good place to start but not the ultimate goal. However, as we found, these topics are quite complex and sometimes difficult to explore with pupils and students. Yet, even so, we should not be afraid to push ourselves and our pupils and students outside our comfort zones. This includes discussing potentially difficult topics such as privilege or global conflicts and resolutions. In order to truly build a transformational global citizenship and language program, we need to critically examine social issues within our local and global communities. Furthermore, teachers must consider how to introduce authentic learning experiences where students can apply these global citizenship concepts and continue to develop their own global citizenship competence.

In conclusion, project teachers and master’s students Hubbard and Torroledo found through their master’s thesis research that a language education curriculum with a strong presence of global citizenship topics and ideas as developed through this project may contribute to the development of students’ attitudes toward the eight global citizenship competencies. Thus, this suggests that future global citizenship programs are an important and necessary component of developing young, open-minded, and globally aware students of the world.

More information about our events and clubs, and most importantly all our supplemental resources such as informational club and pop-up posters and presentations can be found on our website (see link below). We hope the materials will inspire and help teachers to create their own global citizenship lessons and events. https://uefconnect.uef.fi/tutkimusryhma/koulupolulta-maailmankansalaisuuden-valtatielle-ii/

Iris Hubbard and Jenny Torroledo Castillo, both are master's students of the Early Language Education for Intercultural Communication (ELEIC) program, University of Eastern Finland, School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education.

Hanna-Mari Koistinen is a Lecturer of English language, University of Eastern Finland, Tulliportti Teacher Training School.

Ritva Kantelinen is a Professor of Education, especially language pedagogy, University of Eastern Finland, School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education.

References

Almazova, N. I., Kostina, E. A. & Khalyapina, L. P. (2016). The new position of foreign language as education for global citizenship. Vestnik Novosibirskogo Gosudarstvennogo Pedagogičeskogo Universita, 6(4), 7–17. Available from: http://en.sciforedu.ru/system/files/articles/pdf/07almazova_4-16.pdf (https://doi.org/10.15293/2226-3365.1604.01)

Andreotti, V. (2006). Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Development Education: Policy and Practice3, Autumn: 83–98. DOI: 10.1057/9781137324665_2

Brookings Institute (2017). Measuring global citizenship education: A collection of practices and tools. Washington, D.C.

Harshman, A.T. & Merryfield, M. M. (2015). Research in global citizenship education. Information Age Publishing.

Hubbard, I. & Torroledo, J. (2022). Global Citizenship Education in Early Language Education: A comparative study of fourth-grade language curricula and students’ attitudes towards global citizenship competencies from three countries: Colombia, Finland, and the U.S.A.[Master’s thesis, University of Eastern Finland, Philosophical Faculty, School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education]. UEF eRepo Thesis database. Available from: https://erepo.uef.fi/handle/123456789/27345

Morais, D. B. & Ogden, A. C. (2011). Initial Development and Validation of the Global Citizenship Scale. Journal of Studies in International Education, 15(5), 445–466. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315310375308

Schattle, H. (2007). The Practices of Global Citizenship. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

UNESCO (2015). Global citizenship education: Topics and learning objectives. Paris. Available from: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232993 [accessed May 17, 2022].