Come March 2013, and Bhutan will be set fair for its second round of parliamentary elections. While the past five years have been an exploratory phase for Bhutan, in terms of experimenting with and internalizing democratic norms, they nevertheless bear witness to the fact that the formal structures of democracy have indeed taken root in Bhutan. The criteria for assessing the success of democratization towards the end of the fifth year should be gauging the spread of the ‘effective components’ of democracy. One still often comes across the description of “democracy as a gift” (kidu) from the King, but any kind of analysis reveals that the process of democratization has indeed given rise to various stakeholders in the internal politics of Bhutan. How far the internal democratic space impinges on Bhutan’s foreign policy orientations is yet to be seen in the years to come.

Bhutan: the youngest democracy on earth

Bhutan has respected the basic parameters of democracy. The constitution guarantees basic fundamental rights, such as the right to exercise freedom of expression and opinion as well as the right to form associations. There is an independent media and citizens have protection from the arbitrary actions of the state, particularly bodily injury and physical harm. There certainly is separation of powers as different institutions like the Election Commission, the Royal Court of Justice , the Anti Corruption Commission, the National Assembly and the National Council effectively guard and stand by their respective turfs. On electoral procedures, Bhutan has embraced the 'first past the post system' – a competitive system of votes, which makes way for two primary parties to contest the elections. Unlike in 2008, when only two political parties had made their presence visible, in March 2013 there will be five political parties contesting the elections. These are: Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT), People’s Democratic Party (PDP), Bhutan Kuen-Ngyam Party (BKP), Druk Chirwang Tshogpa (DCT) and Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT). While Druk Phuensum Tshogpa, is the incumbent party in Bhutan and has chances of coming to power in the next round of elections too, the People’s Democratic Party is currently the opposition party. Led by Tsering Tobgay, the party has been critical of various socio-economic policies the ruling party in power adheres to.

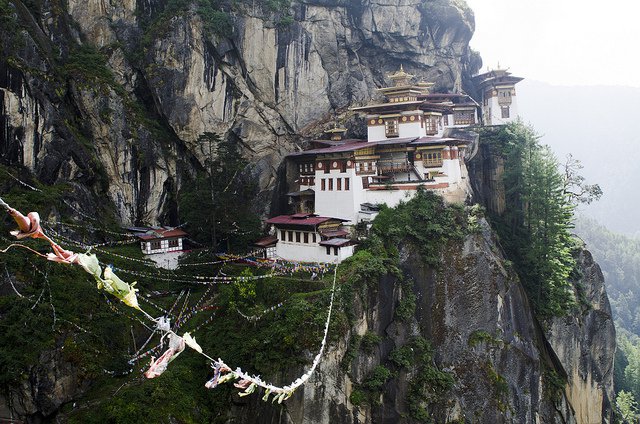

Flickr/ Denis De Mesmaeker. Some rights reserved.

Bhutan Kuen-Ngyam Party is a new party, which focuses on equality. Rup Narayan Adhikari, is the declared party leader. An engineer by profession, he is an old veteran in the private and public sector. Druk Chirwang Tshogpa is another new party in the race and has Ms Lily Wangchuk, a well-known career diplomat and social activist, as its declared leader. Rights of women and the marginalized are claimed to be the main focus of this party. Finally, Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa is also a potential party and focuses on freedom, justice and solidarity as its motto. It has no declared leader at this point. An interesting development is the formation of Druk Me-sar Nazhoen Tshogpa (DMNT), which is driven by Bhutan’s young citizens. Around 50 percent of Bhutan’s population is a young voting constituency and DMNT is a youth collective lobbying for employment. According to The Bhutanese, a leading national daily, DMNT could be a game changer in determining the election outcome in 2013.

Issues and prospects

But how effective have these developments been as they have been applied to the country's challenges? Various issues have triggered some discussion in Bhutan. For instance, Tsering Tobgay, the Opposition Leader, commenting on democracy recently noted the need for intra-party democracy in Bhutan if Bhutan was to successfully pass the test. Charles Tilly in his book Democracy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007) presents a definition such that, “a regime is democratic to the extent that political relations between state and citizens feature broad, equally, protected and mutually binding consultations.” While the first two variables-- broad and equal, entail the criterion of effective citizenship the latter two variables emphasise protection against the arbitrary actions of the state and substantive interaction between the state and citizens. Thus, all citizens ought to be treated equally and to have no significant political rights and obligations based on ethnicity, religion, race or caste, while interests/ pressure groups should have the latitude to influence the institutional structures of the state and its key policies through various means.

Seen from this perspective, the process of democratization in Bhutan is still in the making and perhaps is on the way to take a more coherent shape. This is particularly so, given that the issue of refugees who are settled in the Eastern camps of Nepal is yet to be resolved. There are also nudging questions regarding the Nyingma sect (practiced by the Sharchops) in Eastern Bhutan, who were supposedly ousted from Bhutan in the 1990s. However, these issues are less talked about and are under wraps from public scrutiny. Today, the Kagyu sect of Buddhism has emerged as the dominant strand. While, there have been allegations from detractors like Tek Nath Rizal - a Bhutanese refugee, who has openly spoken against the atrocities imposed on him by the Bhutanese state and King, Bhutan for its part has remained officially silent and is reluctant to discuss such issues in the public domain.

Given active citizen-state interaction as a parameter for effective democracy, domestic spaces have indeed increased in Bhutan. This can be seen in the hydro power sector and the relatively small but growing business community, which has made inroads into the Bhutanese political economy. The significance of these issues came out in the open in July 2012, when a certain tender was given to Global Traders and Gangjung (GT), which is a supplier of Chinese vehicles. The issue was debated in the Bhutan’s domestic media apropos the procedures of transparency associated with the tendering process. Commenting, Lily Wangchuk in a personal interview with the author pointed to the inadequacy of informal spaces in Bhutan which gave ordinary people a platform for voicing their views. She was insistent that while formal structures had taken root, informal groups and collectives to voice the opinion of common people were yet to emerge in Bhutan. She also expressed caution over the growing importance of the business community, which she considered could be harmful to Bhutanese democracy in the long term. The comment was expressed against the backdrop of a discussion concerning the constraints in funding political parties in Bhutan.

While Bhutan has a long way to go in its democratization process, with certain social and economic issues to be pondered upon and taken up by the potential party in power in the years to come , the 2013 elections will definitely pave the way for the future. Much of this future will hang on how the ‘effective components’ shape up in the domestic political space of Bhutan.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.