Protest technologies: can innovation change the balance of power in Russia?

Russian civil society is becoming more effective with the help of technology. But how far does the solidarity created online go?

Crisis situations, whether natural disasters, armed conflicts or political protests are often accompanied by a cycle of technical innovation. And if it’s a question of political conflict, each side tries to use new technology to shift the balance of power in their direction - and neutralise the tools of their opponent. The 2011-2012 fair election protests in Russia are a good example of this kind of innovation cycle.

The Russian state is often unable to react quickly to new technologies, and attempts to counter the advantage gained through radical measures - often, by mobilising law enforcement en masse. In this standoff, the main issue isn’t the outcome of a concrete protest cycle, but the price paid by the state to neutralise it, as well as the extent to which new resources developed by people involved in the process may be used in the future.

Recent events in Moscow show how the dynamics of the “innovation race” have changed over the last few years. Since 2011, Russia’s digital space has undergone a noticeable transformation. On the one hand, the state has imposed much greater regulation of the internet, while investing significant resources in the developing various information technologies. On the other, the opposition has acquired new platforms and new tools: Telegram messaging channels, geochats, chat-bots and so on. And a generation born and brought up in the internet era is coming of age - these people are completely at home with technology and have enormous potential for driving innovation.

Based on open source data, I’ll examine five areas where innovations are being put to use in Russia: protest coordination, protest media coverage, mutual aid, surveillance and elections.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

Protest coordination

The most recent protests in Moscow have been accompanied by mass arrests. Rank and file demonstrators, random pedestrians and well known opposition leaders have all ended up behind bars. This wave of arrests has tested horizontal coordination among activists. Russian opposition leaders such as Alexey Navalny, Yulia Galyamina, Ilya Yashin and Dmitry Gudkov were all cut off from the internet at the same time. Their web accounts are silent, and new coordination strategies have had to be worked out in their absence. Yet the scale of arrests at protest meetings has meant an urgent need for coordinating help.

The first techniques for organising an effective decentralised protest were used in Russia in February 2012. Then, thanks to a specially created platform (today the website is used for a fashion, beauty and celebrities website), protesters organised a human chain (a “White Circle”) around Moscow’s Garden Ring road to literally surround the Kremlin. Unlike a protest happening in a specific place at a specific time, controlling this kind of action required serious resources.

In Russia, protesters’ ability to innovate is growing, and the government may soon find itself at a crossroads

Later, anti-corruption campaigner Alexey Navalny and his supporters tried to use the FireChat app to coordinate protests in real time, as it can link smartphone users who are close by via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi without any need for internet access (a so-called mesh or peer-to-peer network). However, many IT experts questioned the security of this kind of communication, and FireChat didn’t last long in Russian protests.

Then came Telegram channels and Telegram chat rooms. These were symbolic to some extent: Telegram is headed by Pavel Durov, who set up the popular VKontakte social network and was forced to leave Russia after refusing to cooperate with the authorities. Telegram chat rooms and channels were actively used during recent protests.

After arrests at the Sakharov Avenue protest on 10 August this year, some chat rooms started to post anonymous “Where to Go” surveys with possible locations for continuation of protests. The main function of the chat rooms, however, was to monitor movements of the National Guard and special police units (OMON). Chat room users actively exchanged information about which streets were blocked and which areas had been “cleared”, and also discussed how to get out of places where things were hotting up and which escape routes were still open. The word went around: “Be careful, they’re clearing the Maroseyka” and “Get out of Kitay-gorod, if you haven’t already”.

As well as open channels and chat rooms with several thousand users, there are other kinds of chat rooms available. One new development is Telegram’s geochat, which allows people to speak to one another within a limited area. Telegram also runs closed chat rooms, where small groups can gather and coordinate their activities. The open chat rooms and channels are, however, very vulnerable, mainly because they may allow the police to collect information about users.

Yet the main vulnerability of communication technologies, including Telegram, is that they depend on internet access. During the 3 August protests in Moscow, observers from the Internet Protection Society noticed a systemic block on mobile traffic in the area where the protests were taking place. As well as losing access to mobile networks, many cafes had their Wi-Fi switched off. Defenders of internet freedom used an open system to monitor disconnections. This experience has made users think about how to prepare for mass internet “shutdowns” in the future.

But although shutdowns are designed to neutralise protests, they can also have the opposite effect - that is bringing crowds of people out onto the streets. Therefore, we may well see attempts to selectively block individual platforms or their specific functions which are, from the government’s point of view, involved in organising protests. The first step in this direction was a demand from Roskomnadzor (RKN - Russia’s media watchdog) to Google “to stop publicising unauthorised mass events on YouTube”. According to an official government statement, activity on Google can be seen as “interference in sovereign state affairs, as well as hostile influence on, and an obstacle to democratic elections in Russia”.

The latest crisis in Moscow can be seen as an “explosion of social heterogeneity”, whereby people who support the protests discover that some of their social media friends support the suppression of protest activity

Leaving aside the absurdity of accusations levelled at YouTube as a tool for mobilising protests, the fact is that Google is still the most convenient and accessible target for new regulatory initiatives from the Russian government. It is one of the few internet giants to have an official office in Russia. Also, blocking YouTube is technically achievable, while the Russian government has still not succeeded in blocking Telegram, which is actively used by opposition activists.

Covering protests

One of the main factors in covering protests and assessing their success is what researchers call “the logic of numbers”. When protester numbers are being estimated, the official figures and the organisers’ figures are always different. But since 2012, a group of volunteers in Russia - the “White Counter” - has been developing a technology and methodology for arriving at an objective assessment of numbers of protesters (unfortunately, it doesn’t work if the protest is not centralised). The volunteers religiously counted participants at the 10 August protest on Sakharov Avenue, and their figures have become a dependable source for many media outlets (such as the independent Dozhd channel, for example).

Apart from a count, another way of assessing the size of a protest is a visual scan of the size of the crowd. Photos taken from the air have become symbols of protest not only on Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square back in 2011 but also, for example, the Euromaidan protests in Ukraine.

During the 10 August protest in Moscow, numerous general “crowd portraits” were snapped from the roofs (or upper floors) of nearby buildings. The government, however, was able to neutralise another effective tool for judging protest crowd sizes – drones equipped with cameras. Radio Liberty journalists managed to record the police using special technology to “intercept” a drone brought by a protester. But despite these limitations, one of the main elements of protest coverage was a comparison between the size of the crowd on Sakharov Avenue with a “Meat&Beat Festival” organised by the Mayor’s Office at Gorky Park. This kind of analysis is reminiscent of, for example, comparisons between crowd sizes at Barack Obama’s inauguration and that of Donald Trump .

A Dozhd interview with Russian human rights defender Igor Kalyapin from inside a police van, 3 August 2019. Source: YouTube / Maria Popova.

Yet another element in the media coverage of protests in Russia has been live TV reports from inside police vans. These could be watched in the past, but now they are a mass phenomenon that can be seen on both Dozhd and YouTube. The only way to block them would be to systematically confiscate detainees’ mobile phones. In addition, blocking the mobile internet in protest areas would significantly restrict possible live footage for both journalists and protesters.

The effectiveness of media coverage of protests depends on a number of additional technological factors. The work of the OVD-Info initiative, which monitors political arrests, and many other groups has allowed us to collect real data on numbers of detainees at protests. The introduction of free access to the Dozhd TV channel during protests has demonstrated the effectiveness of crowdfunding for supporting continual coverage of events. And thanks to Telegram channels, a new generation of newsmakers has appeared – people like human rights lawyer Pavel Chikov or Ekaterina Shulman, a member of Russia’s Presidential Council for Civil Society and Human Rights. Telegram channels have also helped people follow court cases involving people arrested at protests, sending activists into courtrooms and spreading information about each case (including direct updates from courtrooms on Telegram).

The role of social network algorithms is still debatable where covering protests is concerned. On the one hand, we can imagine that “smart” algorithms work to extend “information bubbles” in which various user groups live in an otherwise diverse info-sphere. If some are concerned mainly with information about protests and detainees, others are indifferent. On the other hand, the latest crisis in Moscow can be seen as an “explosion of social heterogeneity”, whereby people who support the protests discover that some of their social media friends support the suppression of protest activity (and vice versa). This is leading to another wave of social polarisation, mutual “unfriending” and “unfollowing”, which in turn intensifies isolation.

Mutual aid

The wide-scale and spontaneous desire to help that arises in crisis situations can often just lead to chaos and less effective help. Moderators and coordinators turn out to be not enough. As a result, the monitoring of “supply” and “demand” for help at protests has increasingly been automated in Russia. New technologies allow us to create collection and distribution systems that can transform the desire to help into concrete and effective action.

While online maps and crowdsourcing platforms were used to coordinate help previously - for example during the large-scale forest fires in Russia in 2010, in 2019 chat rooms and Telegram channels have become the principal platform for coordination. These channels have been supported by OVD-info, which began in 2011-2012 as a platform for legal help for protest detainees. At the same time, the efforts of chat moderators soon became inadequate for the effective allocation of resources due to the increasing number of tasks and people who wanted to help. For instance, a Telegram chat room that coordinates packages for detainees (“Packages.Moscow”) now has 3,000 members. Chat bots have come to the rescue, helping to automate communication and optimise help so that no one is left unaided, and also to avert situations where some police stations were visited by too many volunteers.

As part of the current Moscow protest, various chat bots have been created for medical, legal or financial help. And for improved coordination, individual Telegram chat rooms have been set up for Moscow’s various districts. They have also been created to provide help around various detention centres. This group of chat rooms and chat bots have turned into a system of connecting vessels, dispatching users to one another, to the correct chat room or coordinator.

Take packages for detainees, for example. A bot asks a user about their situation and intentions (I want to deliver a package/ I want to give money for a package / I have been arrested or detained/ I want to support people in court/medical help is needed) and, depending on the context, offers the user a clear algorithm for the actions and sends it through the appropriate channels. The bot also suggests what foodstuffs and objects should be sent to detainees and where, and how to behave in different situations.

Telegram channels can mobilise a variety of resources for organising in support of detainees

A special chat room for collecting money allowed users to share shop receipts with a list of products bought and then collect the cash needed to pay for them. Another chat, designed to help detained students, helped collect cash to pay administrative fines for taking part in protests. And finally, a “Police taxi” (OVD Taxi) chat room has been set up to help detainees who have left their detention centre after the last metro.

The experience of using mutual aid technology demonstrates that increased effectiveness helps to expand the range of mobilised resources. This time round, the resources have included not just legal aid and emergency food supplies, but also financial, medical and transport help.

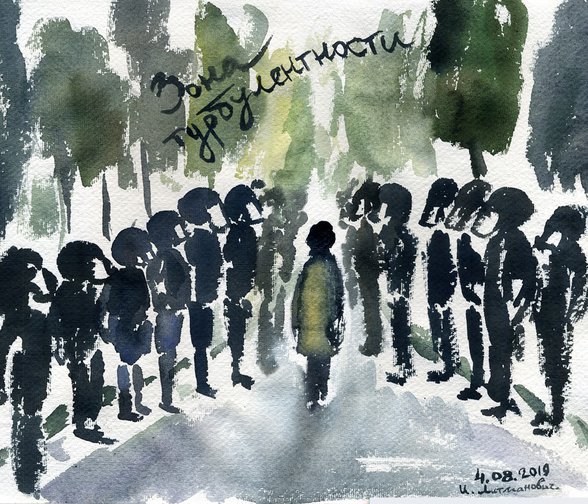

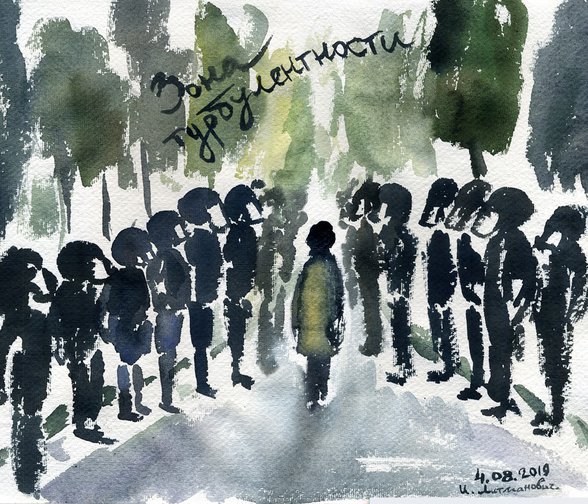

Telegram channels can also mobilise a variety of resources for organising in support of detainees – this can take the form of organising graphic art works to create campaign materials. We must also not forget the mobilisation of programmers to support the work of various information platforms and bring new coordination tools together. The technology of mutual aid is certainly not new, but as the experience of recent events in Moscow shows, Telegram’s functions, including chat rooms and chat bots, have made it possible to create a new horizontal mutual aid ecosystem in the present crisis.

Surveillance

The issue of surveillance is one of the most promising innovation areas for governments in general, and the Russian government in particular. Systems for monitoring social media are constantly being modified. New laws regulating the internet increase the range of data collection targeted at users. Sensors, CCTV and facial recognition allow the state to identify people in crowds (cameras were placed on all metal detectors outside the protest, as well as at the entrance to Sakharov Avenue on 10 August). The openness of the communication world also provides extra sources of information - and allows it to be infiltrated by pro-government agents. And this infiltration is used not only for monitoring purposes, but also for influencing internet channel users.

Today, however, it is not just the Russian government that is introducing new mechanisms for public surveillance. The public is also keen to return the compliment.

An example of this is the creation of projects to identify (de-anonymise) members of Russian law enforcement. Similar technologies have already been used by activists to work with open data (Open Source intelligence) with the aim, for instance, of identifying members of the Russian armed forces involved in bombing raids in Syria. Closer to home, the “Scanner” project has also begun a campaign to publish the identities of law enforcement personnel – police, OMON and National Guard officers who have been involved in the dispersal of the recent protests. The analysis is carried out using numerous services, including Findclone.ru and Yandex Pictures. A de-anonymisation campaign (“We have the right to know who is hitting us”) has been supported by the OVD-Info project.

Most protest technologies are directly connected with protests, but we mustn’t forget about the main reason for them: falsification at elections and during the pre-election stag

On the other hand, the Telegram channels’ anonymity also allows pro-government structures to use personal data to pressure protesters. An example of this tactic has been the publication of a database of personal data of detainees, complete with addresses and phone numbers, on the “Comrade Major” Telegram channel. Some of the people listed began to receive telephone threats after its publication.

The surveillance innovation race continues on both sides of the barrier. Protests in Hong Kong have shown how demonstrators have used lasers to neutralise cameras with facial recognition technology. Every group involved in a political conflict continues to perfect its technology for collecting and analysing data and developing new anonymity technology for neutralising the surveillance technology used by their enemies.

Election technology

Most of the technologies mentioned above are directly connected with protests, but we mustn’t forget about the main reason for them: falsification at elections and during the pre-election stage.

In Russia, the events of 2011-2012 showed the potential of technology, including the mobilisation of observers and exposure of infringements (for example, election monitoring NGO Golos created a virtual map of election violations). Broadly speaking, electoral technologies have two goals: to aid new candidates to take part in an election and to coordinate voter behaviour. An example of this type of technology is the so-called “political Uber” developed by Dmitry Gudkov’s team, which has simplified liberal candidates’ participation in elections by offering them step-by-step online instructions on registration. Alexey Navalny’s “Smart Voting” project aims to weaken the ruling United Russia party’s position. His campaign platform team collects information from hundreds of constituencies and after analysing candidates’ profiles selects alternative candidates to vote for - in order to take seats from the ruling party.

Recent events in Moscow have have shown that one of the main problems here is the supposed invalidity of voters’ signatures gathered on behalf of independent candidates, so one area for innovation could well be the use of new technology to verify signatures.

According to civil technology expert Alexey Sidorenko, the next stage in the development of electoral technology should be politically transparent Customer Relationship Management (CRM), which, among other things, will be able to track the history of every signature. Given the upcoming Moscow elections in September, we could see new technologies capable of monitoring electoral infringements soon.

The dynamics of innovation and the balance of power

New technologies for organising and covering protests are coming up against government countermeasures. Some of these are also technology-based (such as drone interception), but in most cases effective protest neutralisation requires larger police forces and the use of new regulatory practices.

The cost of neutralising a protest, not to mention the possible risks entailed in the methods used, is increasing. Blocking the mobile internet, for example, is expensive, as it involves not only protesters but the entire population of Moscow’s city centre and a wide range of services that require access to global networks. Resources for suppressing a decentralised protest, which necessitate large scale arrests, are also overstretched. The number of law enforcement officers in the protest area should have exceeded the number of protesters, yet Moscow’s police stations could barely cope with the inundation of detainees.

In Russia, protesters’ ability to innovate is growing, and the government may soon find itself at a crossroads. On the one hand, neutralising new technology requires tougher regulations and recourse to more drastic types of force. On the other, drastic measures may provoke a new spiral of protests (blocking the internet might step up the existing eruption of civil society activity). And new technologies might play an unexpected role in this development. The development of satellite internet threatens the effectiveness of new methods of control over the web, while machine learning technology and artificial intelligence (not as yet used by protesters) may play an unpredictable role in the balance of power between government and opposition.

The question also remains of how these latest protests are changing Russian civil society. On the one hand, the mobilisation of mutual aid technology is an example of so-called “connective action”: action requiring no coordination on the part of any leader or organisation that has been enabled by digital platforms. In other words, Russian civil society can be effective without traditional political structures. We can make the case that political crises of this type mobilise and strengthen horizontal structures, simultaneously creating social capital among civil society.

However, the growth in effectiveness of decentralised horizontal protests has its downside. Researcher Zeynep Tufekci believes that “easier mobilisation doesn’t always mean easier success”. According to Tufekci, although information technology allows swift and effective mobilisation, the durability of informal structures and their ability to attain the goals they have set for themselves is still arguable. The easier it is for people to organise themselves, the quicker their emergent horizontal structures fall apart, whilst traditional political structures are stable because they are the result of long and meticulous work.

In a crisis situation, information technologies can allow civil society to become increasingly effective, but in a post-crisis situation, traditional political institutions still have an advantage.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.