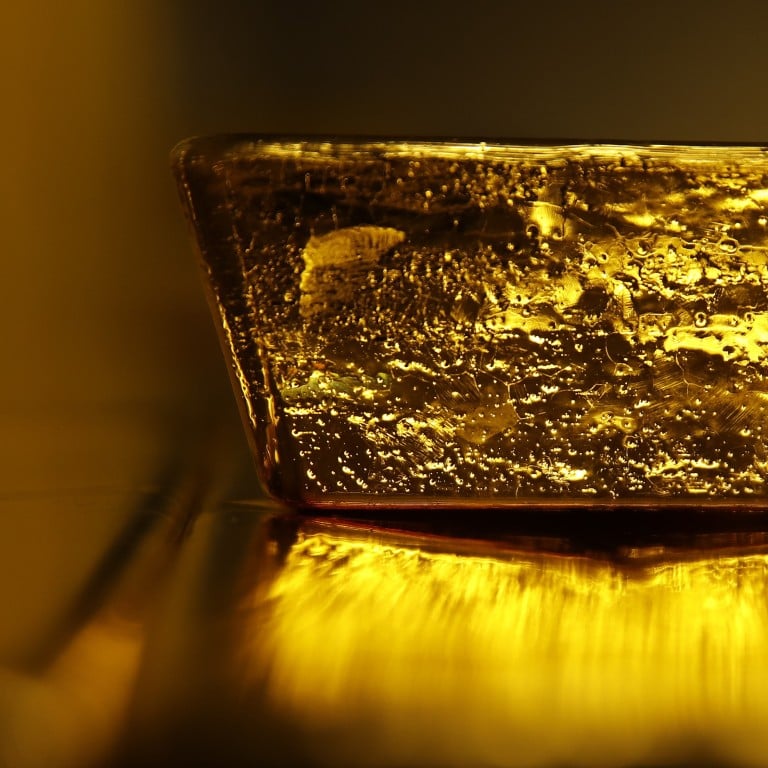

Gold supply heading for peak unless miners ramp up exploration spending, resource consultancy Wood Mackenzie says

- Gold miners slashed their exploration budgets when the gold price fell from the highs of 2011/12 and have kept them low ever since, say analysts

- Global gold output from mines edged up 1.1 per cent in the first half of 2019, a marked slowdown

Gold, one of the more popular risk-hedging tools in the past two months of global turbulence, may see supply peak if miners do not increase their spending on exploration, according to Wood Mackenzie.

The London-based natural resources consultancy said gold producers have kept their spending on discovering new resources under tight control.

The word of caution on supply would support analysts’ prediction that the gold price will head higher in the next two years, having gained 23 per cent in the past 12 months as investors parked more money in the traditional safe-haven asset.

“While the resurgent gold price has garnered a renewed sense of optimism in the industry, it has also shone a light on a structural issue that has been brewing for some time,” said the consultancy’s analysts in a note last week.

Hong Kong shoppers take a break from gold as prices reach six-year peak

“Exploration budgets were slashed following the fall in gold price from the highs in 2011 and 2012 and they have since failed to recover.

“The slight rebound in the past couple of years has not been sufficient to replenish mined ounces and, as such, peak gold supply is now a very real possibility.”

The warning lends support to the views of “gold bulls”, such as David Roche, president and global strategist of London-based investment advisory Independent Strategy, who said in July that the gold price could touch US$2,000 an ounce by year-end.

Citi analysts see that level being reached in two years’ time as fears over recession grow, a view echoed last week by Nolan Watson, chief executive of Canada-based Sandstorm Gold, which provides financing to miners.

Global miners’ exploration spending surged from US$1.2 billion in 2010 to US$1.5 billion in 2011 when the bullion price hit an all-time high of US$1,838, and climbed to a record US$2 billion in 2012, according to Wood MacKenzie.

Hong Kong launches new micro gold trading platform GoldZip

It slumped back to US$1.2 billion in 2013 and stayed in a narrow range of US$800 million to US$1 billion for the next five years.

Untapped miners’ gold reserves rose from 47,000 tonnes a decade ago to a high of 57,000 tonnes in 2016, before falling to 54,000 tonnes in the past two years, according to the US Geological Survey.

The figures reflect a lag effect by which any increase or fall in reserves shows up after exploration spending is raised or cut.

With global industry-proved reserves sufficient to support only 11 more years of mining, Wood Mackenzie said miners have focused on growing their reserves via acquisitions instead of greenfield projects.

Global gold mining acquisitions – led by US-based Newmount Mining – jumped 83 per cent to US$21.8 billion last year, while deals made by Chinese buyers – led by Zijin Mining – surged threefold to US$3.8 billion, according to Refinitiv.

Global gold output from mines edged up 1.1 per cent in the first half from the same period of 2018 as the gold price fell 1 per cent. That was a marked slowdown from an average growth in production of 3.1 per cent in the five years to 2018, and 4.4 per cent in the five years to 2013, data from the USGS and the miners-backed World Gold Council showed.

Production in China – the world’s largest gold miner – has declined because of more stringent environmental regulations. It fell by 2 to 4 per cent in the first two quarters of 2019 on a year-on-year basis, extending declines of 6 per cent both last year and in 2017.

As a safe-haven asset that does not pay interest, 42 per cent of last year’s gold demand was driven by investments and central banks buying for their reserves, according to the World Gold Council.

The gold price is therefore highly sensitive to US interest-rate expectations and the greenback’s movement against other currencies, according to Erik Norland, a senior economist at CME Group, an operator of energy and metal derivatives trading platforms.

“If the equity market sells off and investors come to expect even deeper rate cuts than the 50-75 basis points of additional reductions that markets have already priced in, gold prices could soar [and vice versa],” he said, adding that geopolitical conflicts bode well for gold.

“Meanwhile, rising US budget and trade deficits combined with an easier [US] monetary policy might pull the dollar lower to the likely benefit for gold investors … we are bearish on the dollar and bullish on gold going into the 2020s.”

Weak job numbers in the US pushed the yellow metal’s price up 1.4 per cent on Wednesday to US$1,500, after it fell to a near two-month low of HK$1,464 on Monday amid dampened expectations of further US rate cuts.

After rising above the US$1,500 mark on August 7, it traded as high as US$1,551 on September 4, up 7.6 per cent from a month earlier, on the back of fears of a global recession as the US-China trade war escalated.