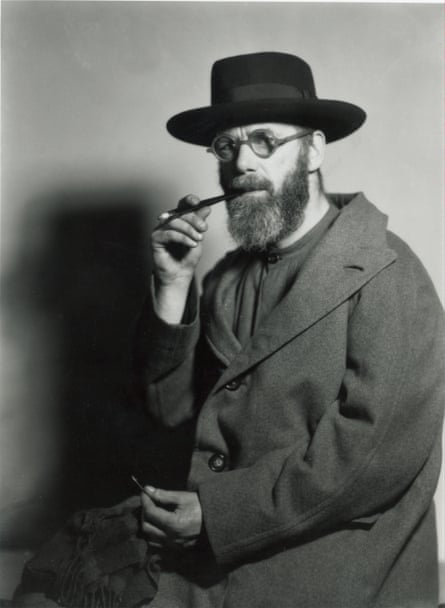

Last October, I was one of 25 delegates at a “workshop day” at the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, a small but beautiful gallery, whose acclaimed spaces are dedicated mostly to displays of work by Eric Gill and the many artists and makers who followed him to the Sussex village after he and his family moved there from London in 1907. Entitled Not Turning a Blind Eye, the purpose of this event was to begin a process that would in time, we were told, lead to the museum dealing “more publicly with the subject of Eric Gill as an abuser”.

I was there at the invitation of the museum’s director, Nathaniel Hepburn, who had read a column I’d once written about the vexed issue of censorship and the arts. Also present were various academics, curators and museum professionals, among them representatives from several major institutions with work by Gill in their own collections – though since all of us agreed to abide by the Chatham House rule I am unable, at this point, to name names.

The atmosphere was friendly and committed, but also subdued. My sense was – I made notes to this effect – that people were slightly uneasy. Perhaps they were worried that, for all their expertise, they did not have the right language to discuss Gill’s behaviour towards his older daughters, Betty and Petra (a sheet we were given on arrival informed us, for instance, that some organisations working in this field believe it is better to use the terminology “a person who has experienced violence” than the words “victim” or “survivor”). Or perhaps they feared how they might sound to others – hard-hearted? Politically incorrect? – were they to be anything less than sombre. Either way, they seemed rather earnest. On the few occasions when nervous laughter did bubble up, it was as if a window had been opened, the room filling briefly with what felt like a blast of clean, fresh air.

The programme consisted of a series of break-out sessions – we split into groups and disappeared into corners – after which, reunited, we engaged in a wider conversation. These sessions encouraged us to consider various contentious objects and the ethical dilemmas they raised, and from the moment they began it was obvious what potentially treacherous territory we were in. Opinions, even among a group of people whose interests and convictions could be said to be broadly similar, were often divided. At the first session in which I took part, for instance, we were presented with a wooden doll Gill carved for his daughter Petra in 1910 (she was then four. He began sexually abusing her when she was a teenager).

Petra is said to have been disappointed with it as a toy, and given its uniform dark brown colour, who could blame her? But I found it strangely alluring. I longed to peel off the white cotton gloves we had to wear when handling it, to feel it with my bare hands.

Others clearly didn’t feel the same. One person thought it – knowing what had gone on in the Gill household – ugly and rather horrible. A discussion followed in which someone asked if its value as art – fairly minimal, in her opinion – would merit its inclusion in any future exhibition; while another suggested that, conversely, it might be a rather useful object in terms of telling Gill’s story: after all, while it connects directly to his daughter, it is not, in and of itself, a controversial object (unlike, say, a nude drawing of her).

And then there was the woman to my right with the striking haircut. She seemed less timid than everyone else. “Look at it, though,” she said, taking it in her hands, and turning it over so that we could see, up close, the ridge formed by the way Gill carved the doll’s luxuriant hair. “She’s got no neck.” What, this woman asked us, did the doll remind us of? When no one replied, she answered her own question. “This is a very potent object,” she announced, running a fingertip slowly over the doll’s head. “It looks to me just like a penis.”

Nathaniel Hepburn became the director of the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft in 2014, eight months after it was formally reopened by Nicholas Serota, the then director of Tate, following a highly successful £2.3m redevelopment (in 2014, it was shortlisted for the Art Fund Museum of the Year). “I was aware of Gill’s biography when I got the job,” he says, when we meet again some months later. “But I think I approached it quite coolly and art-historically. My view as a curator was: he’s an artist, and we show his work. I hadn’t felt it [his biography] would be an issue for us, until one day I found myself looking at work we would feel uncomfortable showing. There was one object in particular, and it really brought home the fact that Gill abused his daughters.”

This was an envelope in the Ditchling archives, on the back of which, in two columns, Gill had listed, in some detail, the measurements of various parts of the bodies of his daughters, Elizabeth (Betty) and Petra. “Adjacent to those are his own measurements and then, at the bottom, he writes his penis size, erect and flaccid. It’s a powerful object. It very quickly tells the story. You can’t look at it and say: ‘He was a sculptor, of course he was interested in measurements and form.’” It was at this point that Hepburn began believing that the museum – which does not currently tell its visitors about Gill’s abuse of his daughters – had a “responsibility” to be “more upfront” about certain facts. “It was a slow process,” he says. “We had to explore how we might do it, or even whether we would.”

First, there were internal discussions among the museum’s staff. Then, tentatively, he talked to the Art Newspaper about what he calls the museum’s self-censorship, its sins of omission in respect of Gill. Gradually, the idea of mounting an exhibition specifically to address the issue of the most uncomfortable aspect of the artist’s biography took hold – an idea that last October’s workshop day was intended to test.

“I didn’t know anything about child abuse,” Hepburn says. “That wasn’t in my training. So I needed to talk to people. I didn’t think we would be starting from scratch. I had assumed that we would find another museum that had already tackled this, and that we would be able to follow their rubric. But they hadn’t, and so we were.” And did the workshop day clarify things? “Yes. Support from the museum sector encouraged us to think we should do this head-on rather than incrementally.”

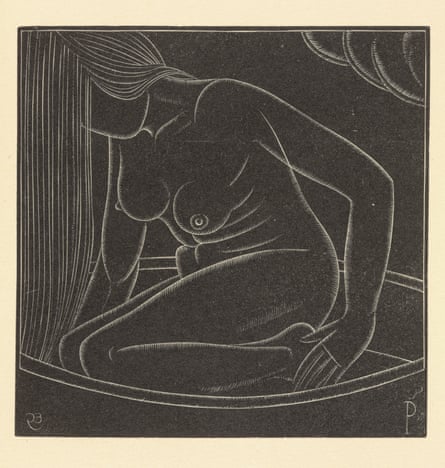

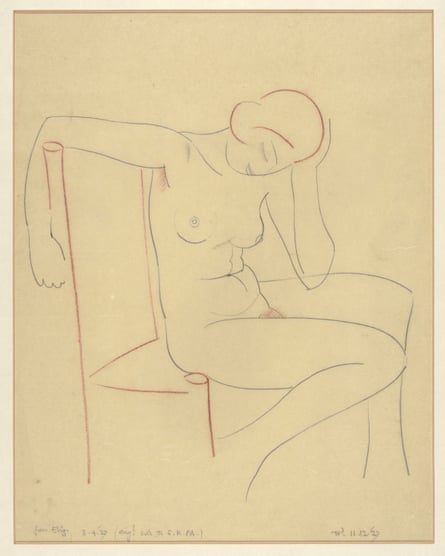

The exhibition in question, which begins on 29 April, will be called Eric Gill: The Body, and one of the first items visitors will see will be the envelope on which Gill pencilled the sizes of his daughters’ busts and waists (it will be displayed in an introductory section beside the old-fashioned smock in which Gill famously liked to work, a nude drawing of Elizabeth from 1927, and On the Tiles, a woodblock of a naked Petra, her face obscured, from 1921). And what about when the show ends? Will that be it? More to the point, can that be it? He shakes his head. “We don’t want to be disingenuous. However, it’s not appropriate to tell this story when you’re looking at, say, Gill’s lettering or religious stone carving. It’s not relevant. Our current thinking is that we will make sure there is always one object on display that enables us to tell the story.”

Meanwhile, even as the deadline for putting the exhibition together approaches, Hepburn continues to consider precisely what else will appear. The problem is that he would like to include some more explicit images of pairs of ecstatic lovers in which the men depicted have erections. “They show happy, sensual, consensual relationships, and to exclude them would, I think, skew the visitor’s understanding of Gill. But this is about understanding our legal position. To include them might mean we have to put some kind of age requirement in place, and we would prefer not to have one. An age requirement would imply that all of the content is inappropriate for children to see, and that isn’t the case at all. These are some of the most remarkable drawings and engravings in British art.” His hope is that these pictures can be shown in a separate, screened-off area, and that the rest of the show can therefore be open to allcomers.

For me, though, the biggest question remains unanswered: why do this show at all? The darknesses in Gill’s life have been public knowledge for almost three decades now, ever since Fiona MacCarthy published her brilliant and wonderfully vivid life of the artist in 1989. It is not as though this information is secret. Why force it on visitors? What, in the end, does Hepburn hope to achieve by doing so? Again, he comes back to censorship: “I don’t want to censor which works we show because we don’t have the confidence of language to be able to interpret them properly.” But there is also the question of “responsibility” to be considered. “Museums have a duty to talk about difficult issues,” he says. “They are a place where society can think. There is some public benefit in organisations like ours not turning a blind eye to abuse. We are very well aware that certain parts of our audience are not going to want to look at this exhibition. But if we lose visitors for this period, so be it. We hope they come back.”

But will they? Isn’t the risk that the museum will henceforth forever be associated in the public mind with one deeply alienating part of the life of the artist most central to its collections?

“Well, we think it’s going to be an amazing exhibition that will show Gill as an amazing artist. It’s not a show about sexual abuse. It asks the question: does the biography change our appreciation of these things?” Does he believe that it does? “At times, yes.” Does he worry about that? “It’s difficult. There’s no unknowing that story. There are certain works of Petra where we know that within weeks of making them, he was abusing her. It certainly affects our enjoyment of that work – it’s as good as it was, but we bring something to it. It does spoil it.”

When it comes to art and life, and to what degree they can or should be separated, he believes people fall on a spectrum. “At one end, there are those who believe biography to be irrelevant; and at the other, there are those who believe he was a disgusting man, and wonder why he should be shown at all. Most are in the middle. Even within the team at Ditchling, different people feel different things. But in the end, the only reason for doing the show is because he is an extraordinary artist.”

Hepburn has talked to groups who work with those who have experienced sexual abuse, and he has accepted some of their advice. Staff and volunteers are receiving extra training ahead of the exhibition, and visitors will receive the numbers of support helplines with their tickets. But if he regards all this as an extra burden, he isn’t letting on. “My trustees are fully aware and supportive,” he says, firmly. Is he nervous about what lies ahead? The current atmosphere is – I surely don’t need to tell him this – censorious. People are easily offended, and disinclined to consider nuance; the mob can be whipped up in as long as it takes to send a few tweets. “As a curator, it’s very interesting,” he says. “This is brilliant work, and we’re exploring a fascinating question. But we don’t have the cushion of being a national organisation: we don’t receive public funding; we are a small charity that depends on visitors and philanthropy. As the museum’s director, I need to minimise the risks to the organisation.”

These are anxious times for those who want to make and show “difficult” art, the kind that attempts to push the boundaries of taste and perception. Increasingly, work is being pulled from public view at the last minute, either because of advice from the police, who may demand huge sums from galleries in order to guarantee the public’s safety (£36,000 was one figure mentioned to me), or because the institution involved simply ran scared of responses to it. One thinks of Exhibit B, an installation by the South African artist Brett Bailey, which was cancelled by the Barbican in 2014 after protests (the work, intended by the artist to explore the issue of colonial racism, involved black actors dressed in chains), or of Isis Threaten Sylvania, a piece by the London-based artist Mimsy, which in 2015 was removed from an exhibition celebrating freedom of expression at the Mall galleries after police raised security concerns (it comprised a series of satirical tableaux featuring the Sylvanian Families toy figurines dressed as terrorists).

Eric Gill, long dead and widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential British artists of the 20th century, seems at first to stand apart from all this – and indeed, in the years after MacCarthy’s biography was published, his reputation only grew. However, following the revelations about Jimmy Savile and others, the atmosphere has begun to shift. In 2014, for instance, the Daily Record reported that some local people were demanding the removal of Gill’s statue of St Michael the Archangel in St Patrick’s Catholic Church, Dumbarton, because it had been “made by a paedophile”. Even in Ditchling, where connections to the Gill family still run deep and where the Museum of Art + Craft is so important to the community, these headlines will spring up. “Villagers furious over plinth for paedophile sculptor”, screamed the Argus last year when, via a retrospective planning application, some locals objected to a sign recognising Gill as the sculptor of Ditchling’s war memorial on the grounds that seeing his name in such a place “sickened” them (the plinth, erected by the Royal British Legion, was eventually removed, on grounds connected to planning permission).

Naturally, the people doing all this objecting often know very little about Gill, save for the fact of his paedophilia, and they trade in misinformation and hearsay. One of those I speak to while researching this piece, for instance, tells me confidently of a protest against Gill’s work by some university students (this, she says, was how she first learned of his abuse of his daughters). But when I try to confirm her story, it pretty much crumbles to dust.

With this in mind, Hepburn’s decision to mount Eric Gill: The Body might be thought rather brave – and certainly this is the word I hear repeatedly from those who support his project. “My overriding sense is that this is quite brave,” says Alistair Brown, a policy officer at the Museums Association. “It’s a test case.” But still, I wonder. Is it courageous, or is it merely foolhardy? And what consequences will it have in the longer run both for Gill’s work and those institutions that are its guardians? Is it possible that Hepburn, in fighting his own museum’s “self-censorship”, will start a ripple effect that ultimately will see more censorship elsewhere, rather than less? And once Gill is dispensed with, where do we go next? Where does this leave, say, artists such as Balthus and Hans Bellmer? Even if their private lives were less reprehensible than Gill’s, their work – that of Balthus betrays a fixation on young girls, while Bellmer is best known for his lifesize pubescent dolls – is surely far more unsettling.

In March, having met with Hepburn three times, I contact some of the big institutions represented at the workshop day. Will the staff who attended talk to me about what kind of precedent the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft might be setting? What happens next first irritates and then slightly alarms me. Those involved want to go through their press offices, which I understand; but once I am in contact with said press offices, I’m informed that no one is willing to speak to me in person – everyone is far too “busy”. Instead, I must email my questions, which they will answer in kind. I suggest this is a somewhat blunt way of discussing issues that are both very sensitive and highly complex. But it is no good. I will just have to await their (presumably) carefully vetted statements.

Most forthcoming is Melissa Hamnett, a curator of sculpture at the V&A. She notes, in her email, that there is an argument that today’s culture has become fixated on biography, and that looking at the work itself is paramount. But she veers away from tackling the issue of what impact the Ditchling show might have on future Gill shows, except to say that she hopes more institutions will be “willing to participate in difficult conversations about Gill’s life in relation to his work”. However, this is positively unguarded compared with what I hear from Stuart Frost, head of interpretation at the British Museum. When I ask if it is sometimes easier not to show an object at all than to tell its full history – a reflection of my worry that this is where the Ditchling project will end up taking us – he comes back with the following: “There is usually a great deal of discussion, debate and deep thought involved in interpreting challenging objects. All of this takes time and resources that museums invest into well-researched and thought-out projects and displays that then enable an object to be considered for display.” I don’t know which question this collection of words is an attempt to answer, but it surely isn’t mine.

The first institution I contact, the Tate, has already had its share of controversies in this area. In 2009, it removed Spiritual America by Richard Prince – in essence, a photograph of a photograph of a 10-year-old Brooke Shields – from its imminent Pop Life show after a visit by the Metropolitan Police; in 2013, it removed 34 prints by Graham Ovenden from its online collection after the artist was convicted of charges of child indecency. But it also has a large collection of work by Gill, including, on permanent display, a sculpture now known as Ecstasy (1910-1), one of the models for which was the artist’s sister Gladys, with whom he had an incestuous relationship that lasted most of his life. Perhaps, then, I should not be surprised when the gallery will only give me a bland, unsigned comment. “Tate’s policy for interpretation is to be open and factual regarding the biography of artists,” it reads. “If Tate is mounting a major exhibition on an artist then there would be detailed biographical information in the interpretation and catalogue. When showing works in the Collection displays there is limited space for fuller biographies, which can be found on Tate’s website.” Somehow, though, I am surprised – or at least, disappointed. And is this robotic press release even wholly true? I look up Ecstasy on the gallery’s website, where I am told all about the influence of Indian art on its creation, but nothing whatsoever about Gladys. The last major Gill retrospective, incidentally, was at the Barbican in 1992. (It defined Gill not by his private life, but as a key figure in early modernism, and a leading advocate of the techniques of “direct carving” later taken up by Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore.)

Could a project such as Hepburn’s lead, paradoxically, to more censorship? “I know what you’re talking about,” says Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship (and another delegate last October). “The kind of care Nathaniel is taking, the kind of resources he is putting in, is potentially a deterrent to others. You can see that people might just quietly remove Gill’s work [rather than go down the same route themselves].”

It is to do, she thinks, with risk aversion. Her organisation has recently received funding from Arts Council England to do more work in this area. “ACE has finally woken up and smelt the coffee, having helped to create an atmosphere of risk aversion themselves. They are very timid, you see. Their funding priorities are to do with an organisation’s business case and its audience development. Freedom of expression is low priority; it’s just an add-on.”

She talks of the Heckler’s Veto and the Daily Mail effect, both of which, coming from left and right, are having a paralysing effect on arts managers. “A pattern is emerging,” she says. “We don’t yet live in a police state: they can’t shut down a show unless it is breaking the law; they can only advise. But the police are very cautious, and if you ignore the advice that something is even only potentially inflammatory, you could be arrested yourself.” It’s a difficult choice: act the censor, or pay the price.

Who, in this climate, will speak up for Gill the artist? Fiona MacCarthy has written vividly of the summer of 1986, when she spent weeks in the Gill collections in the Clark Library at UCLA, reading his diaries. It was there that she found the entries about the incest with his sisters (he may have had a relationship with Angela as well as Gladys) and the sexual abuse of his daughters, and his sexual experiments with a dog. But she has never made any secret of her profound admiration for his work. And whatever she learned in those diaries was always balanced by the fact that she had met so many of those who knew and loved Gill, including his daughter Petra Tegetmeier, who grew up to be a talented weaver and to lead a productive and happy life (experts will insist that she internalised her trauma, but that wasn’t how she thought of it, and I think we must allow her this).

When I contact MacCarthy, she tells me she has watched in “dismay” as the fact of Gill’s abuse of his daughters has grown to become the thing that defines him. “My book was never a book about incest, which is what one would imagine from many hysterical contemporary responses,” she says. “It was a book about the multifaceted life of a multi-talented artist and an absorbingly interesting man.” As people demand the demolition of his sculpture in public places – the Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral, Prospero and Ariel at Broadcasting House – she asks where this will end: “Get rid of Gill, but who chooses the artist with morals so impeccable that they could take his place?”

She has, moreover, serious doubts about the latest approaches to his work. “There’s also the question of whether today’s curators are really equipped to deal with all the possible nuances of the sexual aberrations in the lives of artists, and how to interpret these to the viewing public. I am afraid that in relation to Gill, we are already in the realms of farce. For instance, the curator of the current Arts Council England-funded exhibition at Two Temple Place in London – Sussex Modernism: Retreat and Rebellion – makes the preposterous suggestion that Gill’s move to Sussex was motivated by his wish to set up ‘cloistered communities away from prying eyes’. [Most would argue the move was brought on by his Fabian leanings, his suspicion of London, and his conviction that “life and work and love… should all be in the soup together”.] “I would not deny that Gill’s sex drive was unusually strong and in some cases aberrant,” she says, “but to reduce the motivation of a richly complicated human being to such simplification is ludicrous.” Reducing art to a matter of the sexual irregularities of the artist, she believes, “can only in the end seriously damage our appreciation of the rich possibilities of art in general”.

Like MacCarthy, I can’t wholly endorse what the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft is about to do, for all that its show will include – and here I, too, will speak up for Gill – some of the most exquisite and tender work ever made in this country (if it makes people think about child abuse, this says more about the times in which we live than the work itself).

But I think Hepburn may have one ace to play, in the form of Cathie Pilkington RA, a sculptor he has commissioned to make a piece responding to Gill to run alongside the show. Her installation is, from what I have seen of it so far, going to be remarkable. (Its title is Doll for Petra, after the strange object we met at the start of this piece: Pilkington was the woman with the striking haircut and forthright manner at the workshop day.) Even better, its maker, who is deeply engaged with Gill’s work, is unafraid to attempt to articulate both its mysteries and its controversies.

“The doll is a central device in my work,” she says. “So when Nathaniel told me about Petra’s, I was hooked. Intuitively, I said yes to the commission. I ran towards it. The work has its own life, and I couldn’t keep myself from that engagement. Whatever anyone else said to me – and people did warn me off – I kept returning to it.”

Her installation, central to which are five scaled-up versions of the head of Petra’s doll (one decorated by her 11-year-old daughter, Chloe), will explore different aspects of Gill’s practice, and the way we are inclined to project his life on to his work, sometimes in contradiction of the facts: “The tendency – if there is a picture of a figure – is to chuck all this interpretation on it… it can’t just be a beautiful drawing or a taut piece of carving. But sometimes it is. Where, I’m asking, is Petra in all this? There are aspects to her life apart from the fact that her father had sex with her.”

Pilkington doesn’t feel that knowing Gill’s biography spoils our enjoyment of his work: if anything, it only deepens it; and in the coming weeks, she won’t shy away from telling people so. “This is a bit hard to say,” she tells me, in her east London studio, surrounded by body parts and unseeing eyes, “but the thing I feel behind all of Gill’s work is the libidinous drive of being an artist. When he carved his first figure, he wrote down in excited detail what it felt like to breathe life into material. It was sexual and intimate and God-like, this making of things that could be living, breathing bodies.” She rubs the tips of her fingers together. “That complete obsession: it’s what draws us to Gill, whether we like it or not.”

Eric Gill: The Body is at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, 29 April–3 September

Eric Gill: life and legacy

1882 Born in Brighton, Arthur Eric Rowton Gill is one of 13 children. He studies at Chichester Technical and Art School, before becoming a trainee architect in London.

1903 Gives up his apprenticeship to pursue letter cutting, calligraphy and monumental masonry.

1904 Marries Ethel Hester Moore, with whom he has three daughters, Elizabeth (Betty), Petra and Joanna.

1910 Now living with his family in Ditchling, Sussex, Gill begins carving stone figures. His first major success, Mother and Child, comes two years later.

1913 Converts to Catholicism. According to his biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, he regarded his C of E upbringing as too easy-going, craving instead a more strict religious authority.

1924 Leaves Ditchling with his family, settling in the ruined Benedictine monastery at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains of Wales.

1928 Gill sets up a lettering workshop and printing press at Pigotts near Speen. He goes on to create the typefaces Perpetua and Gill Sans. The latter appears on the front covers of Penguin Classics.

1940 Dies of lung cancer in Harefield hospital, Middlesex.

1989 Fiona MacCarthy’s biography is published and contains revelations about Gill’s private life, based on evidence from his private diaries. Gill’s adulteries and his sexual abuse of his daughters, Petra and Betty and incest with his sister Gladys, become public knowledge.

1992 A retrospective at the Barbican establishes Gill’s place in modern British art

1998 Margaret Kennedy, a campaigner for Ministers and Clergy Sexual Abuse Survivors, calls for the removal of Gill’s Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral. “The very hands that carved the Stations were the hands that abused,” Kennedy says.

2017 Eric Gill: The Body opens at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft on 29 April.