Alec Soth

Minneapolis, Minnesota

A leading chronicler of contemporary American life, Magnum photographer Alec Soth is renowned for his images of disconnected communities in the US. Born and based in Minneapolis, he has published more than 25 books and received a Guggenheim fellowship in 2013

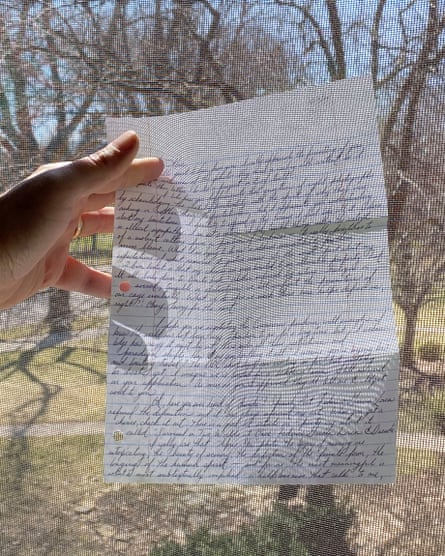

Last year, I began a correspondence with a man who has been in prison since 2003. His letters have taken on new meaning in the wake of the pandemic and the “stay at home” orders. While I would never compare these constraints to incarceration, his words are nonetheless helpful. “It all boils down to limits,” he recently wrote. “Whether enforced by nature – biologic or social, tangible or abstractions – we all confront the parameters of our cage eventually. What we do when we reach those bars helps define us.”

As a photographer I’m really struggling to respond to the pandemic, because I’m not a crisis-response type photographer. I’ve done little photographic experiments, and they’ve been OK. But by far the most meaningful thing that’s happened to me is this letter exchange. In terms of the image itself, I just took a picture of the letter with my iPhone, using the screen on my bedroom window to make the writing illegible, though a few words pop out here and there. I really do find it interesting to reflect on the constraints of prison, which are a million times worse than what I’m going through, and all the psychological weight of incarceration that you can’t even imagine.

I feel like I’m rattling my cage at the moment, but it’s so not a cage. I’m in a city but it’s very spread out. I have a studio, which I have no problem getting to. I’m biking a lot – thank God it’s spring because Minnesota is the coldest part of the US and winters here are brutal. It’s a distressing time, but really my life is not so very different at all. KF

Vanessa Winship

Folkestone, Kent

Lincolnshire-born Vanessa Winship explores concepts of borders, identity and memory in her work, which was the subject of a major exhibition at the Barbican in 2018

Before lockdown a friend sent me a link to a recipe for making vegan honey. All you need is fresh dandelion flowers, sugar, a lemon and water. She suggested that perhaps it was something I could do with my granddaughter, Bella, because she knows we like making things together and doing things outside. Bella is six. In normal times we see each other quite a lot but because we’re trying to obey the lockdown rules I haven’t seen her for many weeks.

Dandelions started to appear opposite my house and along the path where I take my daily walk, so even though I knew I wasn’t going to be making the honey with her, I picked them and I’m planning to follow the recipe. I’m not vegan and neither is she but that is irrelevant, really – I just know it is something she would have loved to do.

It was a coincidence that the cloth on our kitchen table the day I gathered the dandelions happened to have a pattern on it that looks like a beehive. But coincidence is a fantastic thing and I like it when it comes into my work.

I’ve been talking to Bella on Zoom and WhatsApp and because she is a child of the digital age she is very comfortable with that but I can’t go outside with her and pick dandelions so the act of doing that by myself felt like a lovely link with her. What’s really nice as well is that dandelions represent the sun and, in fact, yellow is her favourite colour. I also like the idea that after dandelions are dandelions they become clocks that we blow as a game, counting down the days to the end of our confinement. LO’K

Nadav Kander

London

Winner of the outstanding contribution to photography prize at the 2019 Sony world photography awards, Nadav Kander is an acclaimed landscape and portrait photographer

At the beginning of lockdown, my kneejerk reaction was to come to my studio, set things up and immediately start working. I realised quite quickly that this was an internal pressure I was putting on myself, it wasn’t organic or authentic. I needed more time to process what I was feeling. I knew it was around solitude and touch but I wanted just to spend some weeks digesting it and then see how it comes out in my work rather than pushing.

Part of that process was to bring a camera home and start looking more carefully at my house, turning my eyes on, in a way, and looking more deeply at my surroundings. I started taking pictures inside the house and spent a lot of time looking out of various windows at the plain blue sky without any streaks. One day we had this rainbow and I happened to notice it through the blind.

I find it quite a gentle, poignant image. I like the way the blind drawn between inside and outside asks questions rather than answers them. The clear view would have been less ambiguous, I guess. This is veiled – I think that makes it more alluring.

When lockdown was announced all my projects and the work I had just absolutely evaporated. But in many ways this period has been amazing, not frustrating. There are six of us at home – I have four children aged from 24 to 20 – and I feel very privileged to spend this time with them. I’m actually in my element. I like everything being slower and having time to think and look. I feel more sorry for my children than myself: I think they are bursting to get out and hug people, see people and socialise. LO’K

Eamonn Doyle

Dublin

A record label owner and DJ, Eamonn Doyle returned to photography in 2008, focusing on working-class life on Dublin’s north side. Martin Parr called Doyle’s 2014 book, i, “the best street photobook in a decade”

Just before the pandemic hit, my dad died after a short illness. While the lockdown was going on, I decided to move to his house in Sandycove, south Dublin, to be near my little nephew, who lives next door. It’s the first time I’ve lived out here since the late 80s, and I’ve been taking a lot of photographs around the house where I grew up, which is up the road in Killiney. I’ve been craving to go back into that house for decades and I’d love to photograph it. In the meantime, I’ve been wandering around the area, within two or three roads of the house, just photographing odd things – lampposts, markings on the ground, some surreal hedges – for a short-form publication.

There was something about this trolley that drew me in, I’m not sure what: the particular light, the wall behind it, the direction of the wheels… There aren’t really any supermarkets nearby – the nearest Tesco is a couple of kilometres away – so somebody must have pushed it quite a bit. It’s not part of a narrative or anything. I was just in the mode of focusing on singular objects.

The lockdown has been fine for me. In terms of my day-to-day, it’s been really nice to be out here by the sea, walking around, but I’m very aware that it’s a very unrealistic, unsustainable situation. I don’t feel like I’m going through any heavy grieving or anything – the overriding emotion is one of absolute relief that my dad isn’t dying in hospital right now. That would have been so much worse. KF

Rinko Kawauchi

Chiba prefecture, near Tokyo

Born in Shiga prefecture, Rinko Kawauchi is renowned for her intimate, dream-like images of family life and religious activity in Japan

This is a photograph of my daughter and my friend’s son. They are both three years old and they are looking for an insect in my back yard. It was taken 17 days before the Japanese government announced a state of emergency [on 16 April]. It was the last day of having time together with my friends before lockdown. The children are a metaphor of our future and I hope that future will be surrounded by brightness and light.

The coronavirus crisis has reminded me of the Fukushima nuclear disaster nine years ago. I was living in Tokyo when it happened and I couldn’t walk outside at that time. It’s a different situation now, but I had a similar feeling that the world I live in was changing in a big way.

I haven’t been taking many photographs during the lockdown, apart from at home and at my neighbour’s house. Instead, I’ve been reading books, watching movies and thinking about my new work, as well as doing some printing in my darkroom. It’s a good opportunity to catch up on things like that. KF

Teju Cole

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Teju Cole is a Nigerian-American writer, photographer and critic, whose genre-crossing book Blind Spot was shortlisted for the 2017 Aperture/Paris photobook award

I’m a photographer and I’m a writer, and I keep trying to bring those two things together. One of my ambitions in my photography is to make pictures that look like they were taken by a writer, but in a good way. They’re not just pure emotion, they’re constructed.

I took this image in Cambridge, Massachusetts, within walking distance of my house. What drew me to the scene was the ladders. Ladders are a recurring theme in my work. They are full of metaphorical intensity: a ladder can take you up, but it can also bring you down. And, of course, in many religious positions, ladders suggest heaven. So I walk by this blue house and there’s four ladders – it’s slight ladder overkill. I tried to see what was going on and I saw the man and took a photo.

That was my initial attraction. But once he turned around something had changed, because he was wearing a mask. And I was wearing a mask. The usual element of surveillance that we get in street photography has gone away because I couldn’t identify him. He couldn’t identify me. But a new tension had entered the exchange and that new tension felt to me like a new language that we were all learning to speak at the same time. There is also this cascade of association of what it means when somebody covers their face, and I thought about The Beekeepers and the Birdnester, a drawing by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Emotionally, this is a particularly difficult time to do work. It’s not like: “Oh, it’s a wonderful vacation!” I’m not sitting here writing King Lear. I cannot have that blithe attitude to it, because thousands of people are dying every day. But I think the images I’ve made in the past six weeks have had even more focus and tension than they usually do. And tension is usually what I’m looking for when I choose a photograph. TL

Liz Johnson Artur

Brighton

Ghanaian-Russian photographer Liz Johnson Artur documents the lives of people from the African diaspora. Her first solo show spanning three decades of work ran at the Brooklyn Museum last year

I’m based in London, but I live in Brighton with my family, and a couple of days before lockdown, I decided that probably London wasn’t the place to be. So I went to Brighton. April was a very beautiful month in terms of the weather and this picture was taken in my garden there.

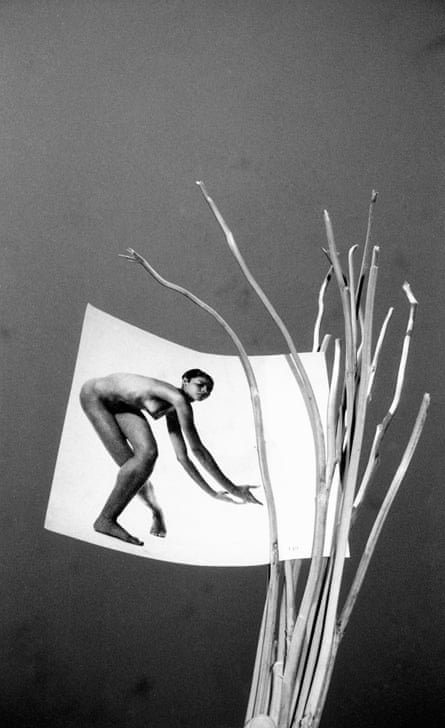

The image is by a photographer called Peter Basch, a German émigré who lived in New York. He did a series of photographs of women in the 1960s, which he called “exotic beauties”. So I was looking at this book and it was badly bound and very windy in the garden, and suddenly all the pages flew off. While I was collecting them, I thought they actually looked quite nice in the garden. There’s a lot of poetry in real life: sometimes it’s there simply by picking something up and combining it with something else that you wouldn’t usually combine it with.

The work that I do as an artist and as a photographer has a lot to do with black and brown representation. On one side, I was aesthetically attracted by Basch’s photographs, but at the same time, I was also irritated by the whole “exotic beauties” setup of the book. This picture felt like a way to give these “exotic beauties” my own kind of interpretation.

It’s a very painful time, and the people that I like to represent are especially affected. But there’s a certain luxury for me in being able to slow down and look at things without any time pressure. In Brighton, I have a 35mm camera and black-and-white film. That’s all I need. Big plans at the moment are hard to accomplish, so I like the idea of small steps and small gestures. This picture is part of that. TL

Newsha Tavakolian

Tehran

The Iranian Magnum photojournalist is renowned for her coverage of conflict and social issues across the Middle East

Iran was one of the first countries to be hit by coronavirus after China, so I wanted to show the outside world my experience of day-to-day life in self-quarantine. Stuck at home, you become more sensitive about details you might otherwise miss. For 17 years, I have been looking at this view of a lampshade at my home in Tehran, but I never thought of taking a picture of it. One night I was bored by myself and I was playing with my camera. I wanted to smoke, so I flicked on my lighter and noticed how the flame lined up nicely with the light from the bulb.

My father passed away exactly a year before this was taken. We were meant to have a big ceremony for the anniversary, but we had to cancel it at the last minute. Instead, my mother, my sister and I went to the cemetery to visit his grave. I was shocked by how quiet it was – we were completely on our own. Then I came home and I was wondering: is this the new normal? It’s like a scary film we are living. Fortunately or unfortunately, nearly two months later, I’ve kind of got used to it. When I want to visit my mother, who lives close by, I put on my face mask without thinking.

If I can say one thing to other photographers and artists , it’s that they must act before this lifestyle becomes normal. Now is the best time to do projects, because everything is new. You’ve got to capture that before you lose your appetite. KF

Giles Duley

Hastings

A documentary photographer focusing on the long-term impact of war, Giles Duley is a triple amputee after stepping on a landmine in Afghanistan

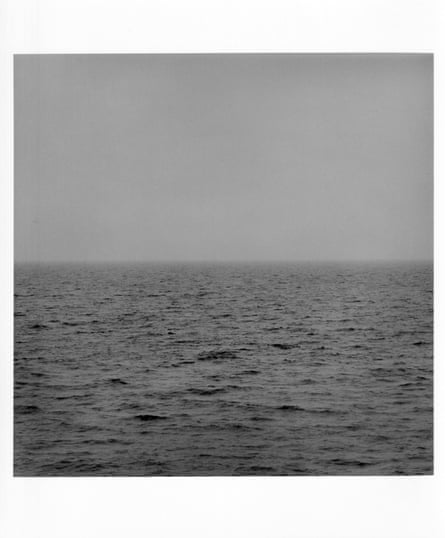

This is the view from my window. Every day since lockdown began I’ve been walking across the road in front of my house and sitting on the bench on the other side to do this kind of meditation for 20 minutes, get my fresh air for the day and take a photograph of the sea.

I moved to live by the sea 20 years ago because when I’m working I am normally in conflict zones, which are tense and stressful places, so when I come back I need peace and I find the sea really helpful. I am not sure if the sea reflects my mood or the mood of the sea is reflected in me but there is definitely a reciprocity of some kind. Often I’ll wake up feeling a bit flat and I look at the sea and find it is a bit flat and grey too. This picture was taken on one of those days.

I’m in isolation on my own. It would be nice to have company but I guess photographers are loners by nature. I’ve been cooking relentlessly – it’s my way to relax – and the button burst off my trousers last week, so I’ll have to watch that.

I’m spending the rest of the time trying to be useful. Through the charity I run, Legacy of War Foundation, I’ve set up a group called Hastings Supports the NHS and we’ve been providing free transport for NHS staff, buying PPE and hand sanitisers for them. It’s been great because the whole community has got involved.

We’re going to auction a print of this photograph to raise more money. I still shoot on film, and by chance one of the world’s best darkroom printers, Robin Bell, lives around the corner from me. So I left the roll of film on my windowsill, and he popped around to collect it and brought back this print a few hours later. LO’K

Alys Tomlinson

London

Named photographer of the year at the 2018 Sony world photography awards, Alys Tomlinson studied anthropology as well as photography. Her 2019 book, Ex Voto, explores Christian pilgrimages

Since the lockdown, I haven’t felt really that inspired to take pictures. Then the other night, I realised I hadn’t been out after dark for over a month. So I decided to go for some night wanders. The American photographer Robert Adams did a series of nightscapes in the 1970s called Summer Nights, Walking. I’ve always really admired that work so I thought I’d explore the area around where I live, in Holloway, north London.

This photograph was taken around 10.30pm on a housing estate near the Emirates Stadium. The day had been warm, but the evening was chilly and there was a strong breeze. So you had the trees blowing, which is quite atmospheric, and then the warmth and pockets of light in the windows of the people getting ready for bed or having a late dinner. Most of my recent work has been shot in black-and-white, although this was digital, because I normally use an old-fashioned 5x4 plate camera. I might have been arrested if I’d got that out.

I was surprised, because it felt eerie and quite unsettling. I’ve lived in London for more than 20 years and never really felt unsafe, but I didn’t really enjoy it, and that probably sums up how I was feeling at that particular moment. There were people lurking in the shadows and it felt odd to be in a neighbourhood I’m so familiar with yet not feel comfortable.

After the lockdown is over, I’ll probably look more towards stories around me. In the past, I’ve never felt that inspired by what’s on my doorstep, but you don’t have to go to the Amazon or Antarctica to make interesting pictures. Also, photographers are all going to be completely skint, so we won’t be able to afford to go away anyway! TL

Chris Steele-Perkins

London

Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins published The Teds, his seminal book on teddy boys, in 1979. He has photographed conflict and deprivation all over the globe, winning the Robert Capa Gold Medal in 1988

I took this self-portrait using the panoramic setting on my iPhone. I rigged up the phone so that it would rotate, and then I jumped in front of the lens and followed it as it moved, turning my head and pulling faces. I had no real control over the outcome, which I found interesting. Sometimes it misses you entirely, and it does strange things to your face. There’s a brutal ugliness about it, and a randomness, which is what’s so freaky about coronavirus – anybody could be struck down for any reason, almost.

When the pandemic started, I didn’t really want to go out, because I’m at risk myself, in principle, and there was nothing I really wanted to document as a documentary photographer. This series (out of more than 150 photos, I got six that I’m happy with) seems like a valid record of this time and how I’m feeling. It expresses some sense of dread, or at least unease.

I’m not feeling like that all the time, thank God, though I’ve had some pretty bleak moments late at night, thinking what else could go wrong with this whole situation. I’m at home in south London, but my wife, who is Japanese, is in Japan. I was meant to be going over there too, but we left it a bit late. I call her every day. Actually, that’s what I’m using my camera for more than anything else: I’ll go out and photograph the garden and then send her an image and say: “Here’s the magnolia coming out.” It’s an alternative to taking photos of my monstrous face. KF