Frederick Seidel is no one’s idea of a protest poet. Born in a well-to-do suburb of St Louis, Missouri, educated at Harvard, encouraged early on by Ezra Pound and Robert Lowell, he has always written from firmly within the establishment. From the beginning, his poems showed an intimate acqaintance with the powerful and the beautiful, and a fascination with the accoutrements of wealth. Seidel is known – in some circles, notorious – for writing poems about Ducatis, and the Concorde, and his tailor. (“Reading Seidel now,” Clive James grumbled, “it saddens me that I have spent my long life dressing like a student.”) His new book, Widening Income Inequality, begins with a reminiscence of Elaine’s, the night spot made famous by Seidel and his jet‑setting friends: “We drank our faces off until the sun arrived, / Night after night, and most of us survived.”

And yet, as the title suggests, this latest collection is attuned to politics, especially the politics of race. Attentive readers know this is nothing new. Racism, violence, the legacy of slavery, the connection between privilege and misery, are constant themes in his poetry. Seidel’s elegy to Michael Brown, “The Ballad of Ferguson, Missouri”, sparked outrage in March 2015 when it appeared in the Paris Review – partly, I think, because it treated the shooting of a black teenager by white police as the latest instalment in a recurring nightmare. For him, Brown’s death evokes the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Seidel’s friend Robert Kennedy - events that have haunted his work for nearly half a century.

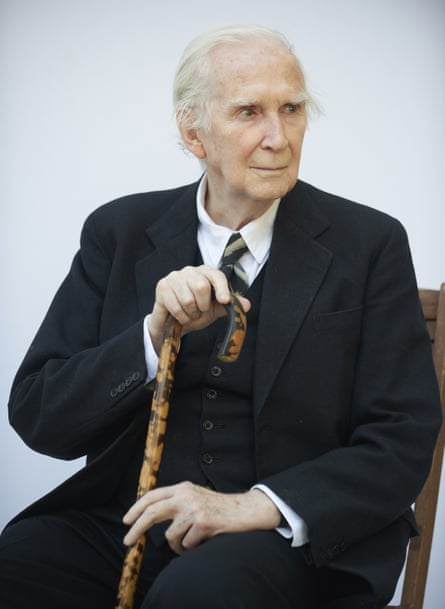

I visited Seidel at his airy, old-fashioned apartment on New York’s Upper West Side. We are speaking on the eve of his 80th birthday. An extremely private man, Seidel has never given a public reading, sat on a panel or accepted an award in person, and he clearly does not enjoy being interviewed, although he answers questions with care and patience. He speaks with what he calls, in one poem, his “Harvard accent”, once common among the north-eastern elite, now a museum piece of poshness: friends are “my dear fellow” or “my dear girl” or, occasionally, “toots”. More than most people, Seidel loves being teased, and his moments of solemnity or eloquence tend to dissolve in laughter, which makes him seem much younger than his age.

Lorin Stein: Where did you get the title Widening Income Inequality?

Frederick Seidel: The phrase has been on my mind, and I felt its, if you like, inappropriateness made it interesting as a title for a book of poems. Within the book the phrase is used with some bitterness and irony.

Is income inequality there in the poems?

Well, the homeless are certainly there. And the wild swing of Broadway is there – by the wild swing I mean, from the feeble and harmed and homeless and helpless to those who stride along prosperously, thinking they are looking very boulevardier and stylish.

A review in the New Yorker began: “If the id had an id, and it wrote poetry, the results might sound like Widening Income Inequality.” Do you recognise the book in that description?

Not really. I mean, yes, of course, but no. No in the sense that, for me, the poems are poems. They were poems as I was writing them, and they are poems as they say goodbye to me. They’re things I worked on. They are works.

As opposed to … ?

As opposed to statements of belief or feeling. It is, I’m willing to grant you, possible to say there is belief and feeling in the poems, but that isn’t what’s going on when I write them. When I write them I’m concerned about the language. I’m concerned with the sound, even with the look of them. Where the lines break and so on.

After your first collection appeared in 1963, you stopped writing for 15 years. Then you started again. You felt, you’ve said, that if you didn’t write again, you would “disappear”. I’ve always wondered what you meant by that.

I feel, when I’m not writing, less well than when I am. When I am writing, I feel that my life is busy. That I’m a creature with a purpose. When I’m not, I feel a bit floaty. Sometimes, not always, that’s not a pleasant feeling. It’s something you have to put up with, of course – you can’t write all the time. But you can write a lot of the time; you can work every day.

In the years when you couldn’t write, is that how you felt? Floaty?

No. It was much stronger, much worse. Seriously, dangerously dire. And I really did feel that my life was, whatever pleasures were in it, pointless. And I’d better be able to write – or. Without quite knowing what the “or” meant. And I wasn’t sure I’d be able to. I couldn’t get the words out, and had to force them out.

May we turn to the new book? One of the poems here is an elegy to the critic Karl Miller.

Karl was a dear friend. He wrote with a wonderful purity and clarity, and fury. He was extremely funny, both in person and in what he had to say on the page. Especially in his reviews.

Do you have a favourite?

I don’t know … though one review of his comes to mind. He told me to read the work of a Scottish poet, at the time hardly known at all, named Sorley MacLean. I was stunned, I was smitten. MacLean wrote in Gaelic but translated his own work into English. Well, after Karl had sent me to MacLean suggesting that I might write something about him, and had heard from me, in my enthusiasm, that I thought I would write something about him, I opened the Listener, of which Karl was the editor, to find that Karl Miller had written an essay on Sorley MacLean! He’d beaten me to it! I saluted.

Another person who turns up in this book – quite a bit – is Apollinaire. There are translations and also a poem of your own that borrows his title “La Jolie Rousse”. Why has he been so much on your mind lately?

Apollinaire has always been with me, in his rhetoric, in his music, the vivacity and melancholy at the same time. “La Jolie Rousse” I think is just one of the great poems. Such a lovely, terrible thing.

The New Yorker reviewer mentions Sylvia Plath and Frank O’Hara as evident influences on your work. Do you think of them that way?

Not Plath, not at all. She has great force, great frightening power, but it’s a bit Grand Guignol. O’Hara is a different matter. His is not my way of writing, but his is pleasurable. It’s lovely to walk around New York with him and meet his friends with him. He obviously was an impossible, delightful, brilliantly gifted man.

Is it true you once wrote a screenplay about him?

I did. The painter David Salle had long wanted to make a movie about Frank O’Hara, and asked me to write the script. I wrote a script. It was not quite up to snuff.

My sense is that you don’t worry much about reviews of your books. Is there a certain kind of criticism that does annoy you, that makes you impatient?

I think it’s too bad, but unsurprising, that this myth of the beautifully outfitted, elegant, elegantly sinister, Baudelaire sort of fellow striding and sliding down the streets of New York has become a way of not talking about the poems. Some reviewers over the years have liked that figure, liked summoning him up. He doesn’t exist, and isn’t really in the poems. Baudelaire is a hero of mine. Baudelaire and how he did it is of great interest. But this persona does get in the way, I think.

What would it mean to actually talk about the poems? What would one talk about?

How they sound. What they’re like to read, for pleasure and instruction. Something like that. In other words, they would be poems that you read because you wanted to read poems. Rather than, say, [the gossip column] Page Six of the New York Post.

But that kind of enjoyment can be hard to convey in a review. What are you supposed to say? That a poem makes you cry? That’s not much of a response.

I like that response.

And yet it’s hard to work into a review.

I quite understand. But personally, I enjoy someone saying to me: I very much enjoyed that poem, I was moved by that poem, that poem really surprised me. I like the simplicity of statements of that sort. I understand they do not a review make, however large their meaning may be, or however much they may contain. They don’t lead to further discussion.

Does it bother you when readers get angry about your poems, as for example when “The Ballad of Ferguson” was published in the Paris Review?

The honest answer is that I’m largely indifferent. I was puzzled by that reaction, and thought however well-meaning – at least I think it was well-meaning – it was slightly preposterous that there were people offended by “The Ballad of Ferguson”. To go back to what I said a moment ago, I like it when somebody is moved by a poem. I like it when someone likes a poem. But that’s about it. What interests me is writing them. Some guy in the London Review of Books’ blog recently called me Kanye Baudelaire. I like that.

Are you worried about Trump as nominee?

While I’m not missing all the remarks made that Trump would be the best friend the Democrats could have, I don’t find myself confident about any of that. All along people have discounted the possibility of Trump doing well, and he’s doing very well.

What do you think the sceptics are missing?

What they’re missing is the pleasure people are taking, the relief they are feeling, in Trump’s speaking in the outlandish way that he does, saying stuff that makes them feel their yearnings, their demands, are heard. Here is someone for them – “them” being that apparently large group of people who understandably feel that the politics of the country are not responding to them, are not listening to them. They feel that politics is going on independently of the electorate, that it’s a thing in itself.

You were excited about Obama.

Very. I still am. I understand the disappointment some people feel. But I think he’s been superb.

Do you think of yourself as a person of the left?

No, though I am. Rightish left.

What’s the part that seems more rightish, and the part that seems more leftish?

I think I have a sort of righty fury and contempt for grandiose lefty claims of having found the true path, the correct way to do things. It is, for me, appropriate and necessary to be critical of the left. On the other hand, the right I have no sympathy for at all. It’s so obviously ignorant and brutal that one almost dismisses it. One is frightened by it now and again, but dismissively frightened.

As a general rule, it seems to me, British and American poets don’t have much to do with each other these days. You are an exception – you publish almost as much there as here. Many of the critics who write about your work are English. Do you feel at home in England?

Not really. There have been periods when I spent so much time there that, flying back and forth, I would get confused about which was home. But I’ve also lived in Paris for very long periods of time, and in France in the country. I’ve spent a great deal of time in Italy, practically living there. And always, in those days, when I’d been away from the streets of New York for a long enough while, I missed them – the vividness. The openness. The mixing of blacks, Latinos and whites. It’s often remarked by English people, either living here or visiting, how friendly – it is almost a cliche – how sunny Americans are. The famous New York aggression bursts into a smile of helpfulness. New York is my place.

You are thinking of the Upper West Side specifically.

I am. Early on, in the 60s, it was a near miss that I didn’t go to live in Greenwich Village. After Franz Kline died, his old studio was being rented out as an apartment. My then wife and I almost took it, which I used to think – in the days when I thought about this – would have changed my life completely.

Well, you’d talk different.

[Laughs] Absolutely. But it wasn’t the case. First I lived in the Upper East Side, for decades. Then I lived in the country, in the plush, flush Westchester Eden, an hour out of New York. And then came back to the Upper West Side, which I had not known at all, but which now I feel is where I was born. Reborn. In those days it was very raffish and rascally. Drug dealers everywhere, prostitutes everywhere in the streets. And wonderful.

It’s not like that now.

It certainly isn’t. When I was young and living in London and outside London, in Kent, London had its own energy and troublemaking excitement. I knew Francis Bacon a bit, I drank with him and that vehement crowd. The nightlife, the daytimes seemed magic and exciting and different.

And now? What do you go back to, in London, nowadays?

Mount Street Gardens – a very small, powerfully beautiful little park by the Farm Street church, and across from [gunmaker] Purdey’s and their shotguns. Which is itself a wonderful place to visit now and again. I’m now very used to Mayfair, and enjoy it.

You don’t find it … empty?

It’s not a place that emits gusto [laughs]. But it’s very pretty. Museums are near enough. I don’t know what else to say. A lot of the people who mattered to me in the 60s and 70s are, of course, gone – Karl Miller, Frank Kermode, Ian Hamilton, Richard Wollheim. A lot of funny people. I loved it that you could go into a porn shop in Soho, and be rifling through the stuff in back – that’s where they kept the real stuff, really the real stuff – and there would be Wollheim.

Or Seidel.

Or Seidel. I do love the English toleration of oddity – the celebration of oddity, really. People walking around with four arms poking out, five different versions of themselves, such unexpectedness. I think of Ronnie Laing – RD Laing, the psychiatrist – and his entourage of former patients who had gone on to be analysts themselves. These were very often people with serious musical talent, as Laing had. He played the clavier and the harpsichord both. It was very striking to go to Laing’s and see everybody smoking their special weeds – the perfume of those special weeds thick in the air – and to lie down on the floor and above you would be Laing or an acolyte playing some Scarlatti. All that could be alarming, or some of it, but superb.

- Widening Income Inequality is published by Faber at £14.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion