With a net worth of around $140bn, Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos is now the richest person in the world. That distinction has come at the expense of Amazon’s workers. In order for those workers to begin sharing in the vast wealth their labor has afforded Bezos and other Amazon executives, they need a union.

Since Amazon’s founding in 1994, the company has successfully suppressed all efforts by its employees to unionize and improve working conditions. A few years ago, maintenance and repair technicians at Amazon filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board announcing their intention to form what would have been Amazon’s first union. Amazon immediately hired a law firm to suppress the organizing effort.

In January 2014, under intense pressure from management, the maintenance and repair workers voted against unionizing.

In 2000, after an arm of the Communication Workers of America attempted to organize customer service employees, Amazon responded by shutting down the call center where they worked. (The company claimed, unpersuasively, that the firings weren’t related.) The same year, the New York Times reported that Amazon’s internal website for managers included instructions on detecting and busting unionizing efforts. In 2016, the Times exposed a manager at an Amazon warehouse in Delaware who made up an anti-union story to scare employees off organizing. According to the Times, several employees appeared to have been fired for advocating a union.

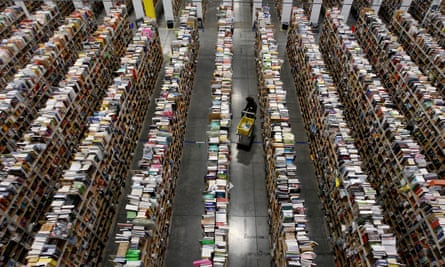

While Amazon has been diligently working to shut down any prospect of its workers unionizing, investigative journalists and activists have uncovered widespread abuses of workers. Ambulances were called to British Amazon warehouses 600 times in three years. James Bloodworth, a writer who went undercover at an Amazon warehouse in Staffordshire, England, discovered that workers there routinely urinated in water bottles to avoid being punished for taking breaks from work.

Similar conditions have been reported in the United States. In a 2011 essay for the Atlantic, writer Vanessa Veselka shared her experiences working at an Amazon warehouse outside Seattle. She described how employees were forced to work in robotic, fast-paced conditions. Veselka was eventually fired from her temp position at the warehouse after she attempted to organize a union. More recently, warehouse workers told Business Insider about time-crunched employees using trash bins to go to the bathroom. Employees also described a work atmosphere predicated on fear of missing productivity targets, and said that employees spent most of their lunch breaks waiting in line for onerous security screenings. Former Amazon workers have also said they are pressured to under-report warehouse injuries.

Amazon workers are not paid wages that reflect these strenuous working conditions. In at least four states, the company is one of the top 20 employers of people dependent on food stamps. In a 2017 corporate filing, Amazon reported that the median salary of its employees is $28,446, or roughly $13.68 an hour for full-time employees. Jeff Bezos makes more than that every nine seconds.

In fact the very presence of Amazon warehouses in a given area may drive down local warehouse wages, according to the Economist, which cited declines of more than 30% in Lexington county, South Carolina, 17% in Chesterfield, Virginia, and 16% in Tracy, California. Amazon also appears to have a negative impact on job growth: The company “employs just 19 people per $10m in sales, compared to 47 people per $10m in sales at local brick-and-mortar retailers”, the Institute for Local Self Reliance wrote in 2015. “This means that as Amazon grows and crowds out other businesses, the result is a net decrease in jobs.”

Amazon’s tendency to locate its warehouses in rural areas also makes it more difficult for workers to leave Amazon to find higher paying work – though Amazon still has one of the highest employee turnover rates in corporate America. According to PayScale, Amazon’s employee-turnover rates are the second worst of all Fortune 500 companies. In addition, a large portion of the company’s employees are temporary; the company regularly hires 120,000 seasonal employees to handle extra workloads during the holidays.

Those who do stay on as full-time employees are pushed to their physical limits – making it all the more difficult for workers to find time and energy to organize for collective rights.

In Europe, Amazon workers have found more success. In March, Amazon workers at a warehouse in San Fernando de Henares, Spain, received union support as they organized their first strike, joining similar strikes in Germany and Italy. In Italy, after strikes and protests, Amazon recently agreed to end unfair scheduling practices.

Though Amazon has suppressed union efforts in the US, campaigners in Seattle recently made a heroic effort to push back on the campaign’s bullying. Last month, local leaders and activists there successfully lobbied the Seattle city council to pass a “head tax” on Seattle corporations grossing more than $20m in revenue. Advocates in favor of the tax argued that Amazon, which paid no federal taxes in 2017, should contribute to funding city services; such tax revenue could be used for affordable housing and homeless services. Amazon responded to the tax by threatening to scale back its business in Seattle. As a testament to the political power Amazon wields, the Seattle city council repealed the tax with no replacement just a month after the same council members unanimously passed it.

The lesson from that episode seems to be that only unions, not local legislation, can really hold Amazon accountable to its workers.

Amazon’s workforce more than doubled between 2015 to 2018, thanks to rapid growth and the company’s acquisition of Whole Foods, which added 87,000 employees to Amazon’s global workforce of around 566,000. Amid an American economy crippled by stagnant wages and the highest income and wealth inequality since the Great Depression, Amazon’s workforce continues to grow. The reality is that the decline of America’s traditional retail industry has left a void that corporate titans like Amazon will continue to exploit – unless employees, unions and Amazon customers work together to raise wages and improve working conditions.