It’s not as if no one saw it coming. The decline of physical shopping, the business of getting yourself to an actual place and receiving actual goods from an actual person in return for actual cash, has been predicted – prematurely, as it turned out — since the end of the last century. It was not news in 2011 when David Cameron’s government appointed the retail consultant and broadcaster Mary Portas as a “high street tsar”, in an attempt to reverse their failing fortunes. Still less was it news in 2017, when the pitifully tiny £1.2m that she was given to revive 12 “pilot” towns unsurprisingly failed, with 969 units having closed during the initiative.

One could choose other landmarks along the journey, the point in 2015, for example, when Amazon surpassed Walmart as the most valuable retailer in the United States, or the moment in February when it came to be worth 2.5 Wallmarts. This year, in Britain at least, has been a particularly bleak one for those businesses that somehow seemed part of the national furniture. Well known names such as Toys R Us, Maplin, Debenhams, House of Fraser, Evans Cycles and Mothercare have been either shrunk or terminated, with 85,000 retail jobs lost in the first nine months of 2018.

One symptom could be found on Black Friday, the hideous sales-boosting device imported from the US. Over there, on the day after Thanksgiving, shoppers are beating down the doors in search of bargains. Over here, despite the lack of a national meaningful date or public holiday, they have been encouraged to do the same. The only problem is that, this year, the sales generated by Black Friday are more and more heading online.

One by one, the things that used to be done only by shops have been picked off. Travel agencies, video rentals, banks and bookshops are now joined on the endangered list by takeaways, which might have been thought an imperishable fixture, thanks to delivery services such as Deliveroo. It would be dumb to foretell their complete demise, especially in high-value places like the west end of London, but shops, like CDs and DVDs, like typewriters, film photography and answering machines before them, are losing their quality of inevitability.

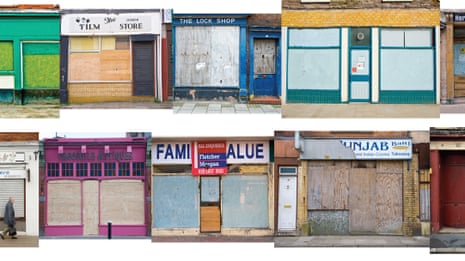

The difference with shopping is that its departure is leaving behind swaths of redundant urban fabric. The identity and self-esteem of entire towns and city districts is wrapped up with retail – what, for example, is a “market town” if it doesn’t have a market? As it has become ingrained that one of the main forms of shared public life is shopping, its loss becomes an existential threat to society. The idea is summed up in the phrase “high street”, which carries with it ideas of locality and community, but is also routinely used as shorthand for “shopping”. The term “high street brands” gets applied to chains of stores that have no presence in high streets, but only in shopping centres and malls.

The resulting voids will be of the scale of those left by the closure of docks and factories, with the difference that those left by retail will often be in the centres of towns and cities. A fundamental turning around is in prospect of the ways that towns and cities are inhabited. It might, for example, lead to yet more centripetal and atomised forms of existence, a world of cocoons, as physically isolated as they are digitally connected. It might, to look on the bright side, lead to a rediscovery of the things we like about human contact. For it required an impoverished view of civic life that it ended up being so dependent on shopping. And it is because the pleasures of shopping had become so meagre that it became vulnerable to takeover by the internet.

It is important, in the great sweep of things, to distinguish between different types of physical shopping. There are markets, high streets, shopping centres, department stores, retail parks and megamalls. Until now, these types have tended to be at war with one another – the battle of the high street against the mall has been going for decades – and they still are, even though they all have a common rival in the internet. They are likely to have different fates of different significance: what happens when a town centre loses its life and purpose counts for more than the disappearance of an out-of-town mall, which mostly leaves a brownfield site that might be used for, say, housing. It is also important to note differences between geographical locations and levels of prosperity. Dwellers in big cities have certain kinds of relationship to what might be called their high streets; those of rural towns have another.

What you hear from more or less everyone concerned with physical retail is that the future lies in offering things that the internet can’t, in providing for the needs of humans as social and embodied beings. Just as the retreat of other media has created nostalgic reactions – for vinyl, for film, for manual typewriters – so retail experts now like to talk about the importance of “experience”. This can mean, for example, what the now ex-tsar Mary Portas has called the “brand temples” by which Nespresso immerses customers in the world of coffee capsules, or Dyson in the world of domestic appliance, curated, calibrated environments in which the actual product is made precious by its lack of abundance.

One of the more ebullient figures in the field is Lara Marrero, of the architects Gensler, for whom almost everything is positive. For her it’s less a case of death than reincarnation, the emergence of a bright new world in which a brand “is engaging its customers at every single touch-point”, in which physical spaces work with events and social media to enthral their followers. Here we are rewarded for surrendering “an incredible amount of value” – that is, the personal information we carelessly scatter about the internet – by being offered experiences perfectly tailored to our desires. After which, of course, we reward the brands for rewarding us by buying their products.

In this new world, a brand’s chief marketing officer is “at the root of everything”, a maestro pulling the strings of data and desire. They can identify the wants not only of their clientele, but niches of that clientele, and then hold (for example) pop-up events that perfectly serve those wants. They can “own everything from start to finish and have a real community about it”.

She talks, for example, of “Sephoria”, a two-day pop-up created by the cosmetics brand Sephora in Los Angeles, in which you could, as the blurb had it, “run wild through rooms brimming with one-of-a-kind beauty experiences”. You could get makeup masterclasses and customise products. You could “celebrate the often indescribable euphoria you get from playing in the vast world of beauty”, as Sephora also put it. You could enjoy “plenty of Instagrammable moments”, such that the whole giddy pageant of social media and lived moments could go tumbling on.

As part of this discovery of “experience” tech companies have started to irrigate the landscape they previously helped to parch. Amazon, having caused countless bookshops to close, is now opening some of their own , with warm woody surfaces approximately as bookshops are supposed to have. Amazon also acquired the Whole Foods organic supermarket chain, with its wholesome and enticing produce. Apple have started calling their stores “town squares” and are trying to shape the public realm around them.

All those aspects of being human, in other words, that somehow got mislaid in the evolution of shopping from market to high street to mall to internet, that is to say sensuality, sociability, enfranchisement and exploration, the possession of a body and existing in nature, are to be reinstated by fast-moving brands and their wizarding CMOs, made omniscient by the personal data they have harvested from us. And, to the extent that physical retail had become a cheerless activity conducted in skimpily decorated and harshly lit boxes, good luck to them. I am happy for whatever happiness the citizens of Sephoria found in its two-day existence, and pleased if retail gets back some of the creativity that it had in the glory days of department stores.

Observer readers will, however, have spotted the snag, which is that Apple or Amazon are not the same thing as the civic guardians of the public realm that we had before. The citizens of Stockholm spotted this too, when they opposed Apple’s plans to colonise, in the nicest possible way, one of the city’s squares. A new Amazon bookshop does not substitute for the multiple forms and idiosyncrasies that you get from a mixed economy of independents and chains. It is a rehydration, a low-res digital copy, a bookshop-droid. It might be asked too if a city of niches and pop-ups, of short-lived singularities, is going to fill the gaps left by old-fashioned shops.

There are, luckily, more everyday forms of “experience” than these high-concept productions. If the hardware store that Ken and Sue Greenwood run in Market Rasen, Lincolnshire, is a long away from Sephoria, they too ascribe the fact that their 27-year-old business is “holding its own” to the provision of something you can’t get on a computer. In this case it is “service”, cutting keys and fitting blinds, and the fact that “people know they can rely on us. The staff has always been there.” They also note that it is shops offering services – hairdressers, beauty salons – that are opening up in the town, which is one of those Portas Pilots for which one-twelfth of the government’s £1.2m wasn’t enough to make much difference. It is an observation that accords with national figures that show that such businesses are doing better than most, and with a belief of Lara Marrero’s that local high streets can also join in her bright new world of experience. She also thinks that there should be more places for fitness and communal gaming, which would require a change in the planning policies that currently stop shops from being converted to these uses.

For Bill Grimsey, a former CEO of Iceland who now publishes reports about the future of the high street, every town has the ability to reinvent itself as “something bigger than shops”. Retailers “spent the whole of the last century cloning every town and it doesn’t work. Zara, John Lewis: how boring is that?” Rather, he says, they can draw on their individual identities, on local produce, heritage, culture, art and crafts, to attract people. “Every town can be its own Disneyworld,” he says. “Every town can be its own ‘wow.’”

If this sounds optimistic, he offers the example of Stockton-on-Tees, which “should be bottled up and taken to every town centre in the country.” Here, according to the local council’s chief executive Neil Schneider, “we decided to reacquaint ourselves with our history”, which means not only its role in the birth of railways but seven centuries as a market town. Historic buildings were revived. An amphitheatre, equipped for theatrical lighting and sound, was created in the re-landscaped town centre. A programme of events – performance, music, cycling, a car show – was launched. New independent shops are incubated. Activities – classes in pottery or sewing for example – are offered as well as products. New homes are being built so that people can live in the centre.

“The most difficult bit is public expectation,” says Schneider. “If you haven’t got a high street with a Marks & Spencer or a John Lewis, then it’s failing. But that’s not true.” This could indeed be the moment to pause and ask if shopping should actually characterise cities to the extent that it does. Not so long ago, commentators used to reflect on how everything – museums, airports, railway stations, Unesco world heritage sites – was becoming one great tissue of retail. Hands were wrung over its influence. Hard-up towns like Hastings and Hull felt obliged to trade their assets – a delightful cricket ground in the centre of the former, and expanses of water in the heart of the latter – for the financial benefits of shopping centres. If these decisions seemed questionable when they were made, they would be more so now.

London’s Oxford Street, for one, could be set free. For decades, proposals have come and gone – monorails, pedestrianisation – for civilising Oxford Street, whose problems arise from its being too narrow for the crowds it attracts. But what if its multistorey volumes of retail diminished, leaving showrooms at ground level and places to live and work above? There would be fewer, calmer, happier people, a more enriching range of life, and no need for ambitious traffic engineering.

Geoff Mulgan, chief executive of the National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts (Nesta), considers “what you would do if you were designing a city from scratch”. You would have “learning zones” (by which he means areas shaped around universities) and neighbourhoods suited to ageing populations, and layouts designed to encourage public health through walking and through access to healthy eating. These elements would not be hermetically sealed from one another but open and connected.

This sounds quite like a traditional city – Oxford, say – give or take some adjustment for the greater scale of modern life. It would be a challenge, as Mulgan says, to retrofit it into existing fabric, but not an insuperable one. Tŷ Pawb, the arts centre formed within an underused market building in Wrexham, gives an idea how it might be done.

Much of the repurposing of retail space can come from the bottom up, if it is allowed to. As happened with abandoned warehouses, new life occupies the slack space, made possible by low or nonexistent rents. The types are well-known – startups, artists’ studios, pioneer cafes, co-operative housing – but none the worse for that. An organisation called the Empty Shops Network, now 10 years old, helps artists and performers reuse redundant spaces. Among those they have helped is the Shopfront theatre in Coventry, formed out of an old fish and chip restaurant. In Elephant and Castle and Seven Sisters market, in south and north London respectively, shops and stalls serving the specific needs of local communities grew up in the margins left by what were (in commercial terms) unsuccessful shopping centres. Both, however, have been threatened with destruction precisely because they were considered commercially unsuccessful.

Forms of sociability that do not rely on the adrenaline of consumption and events might also grow up. Might an empty shop, with minimal expenditure, become an informal library, stocked with second-hand books and DVDs, a gentle alliance of old tech devices and architecture, possibly for old-ish people? Or might it be just a public living room or informal club in which you might escape the isolation of private space? Might planters be permitted on the pavement, tended by the users of the different premises? Places like Bonnington Square in south London, a 1970s squat that is now a verdant tourist attraction, show how this can be done.

If a high street had a number of such places it would become a truer community than one where people are rushing between chain stores. Which is not to say that this, or any of the other bright ideas about retail space will happen easily or everywhere. A lot of retail space is in the form of large, sealed black boxes, which make them less adaptable than characterful Victorian warehouses. Middle-sized shopping centres in town centres, with no special character, will be especially challenging.

The government has again decided that something must be done. “The British have taken to online shopping like no other nation on Earth,” said the chancellor, Philip Hammond, in advance of his recent budget, in which he promised £1.5bn of help to small retailers.

He delivered in his measured tones the same message as breathy brand consultants, that it’s not about stuff any more, but experience: “The high street of the future frankly will have fewer retail outlets and more leisure destinations, more food and drink outlets.”

This is all sane and fine, although there was criticism that the £1.5bn wasn’t enough. But there is something bigger here, which is to make, as the old saw has it, an opportunity out of a problem. Rather than a rearguard action in defence of something we may not miss that much, there is a chance to revive what is actually good about towns and cities. If the retail kraken is enfeebled, it is time to escape its tentacles.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion