On the evening of 20 August 1944, the commander of the Paris area resistance and his secretary emerged from an underground passageway into the basement of an elegant 18th-century pavilion on the avenue that now bears his name.

Six years earlier, and two years before the Nazi occupation, the basement had been transformed into a control centre for key city services in the event of an air raid, but never used. It housed, among other useful amenities, a private, 250-line telephone exchange.

It was perfect. Henri Rol-Tanguy, known as Colonel Rol, his wife Cécile and their comrades swiftly began setting up the subterranean command post from which, over the next five days, the final battle for the liberation of Paris would be run.

Amid a bloody city-wide insurrection that ended on 25 August after US and Free French troops arrived, the occupying Nazis surrendered, the tricolour was hoisted from the Eiffel Tower and Charles de Gaulle made his trumphant entry into the capital, as many as 1,000 résistants lost their lives.

Now, three-quarters of a century later, their fight, and the story of occupied Paris, is to be commemorated by a striking new museum housed in that same elegant pavilion on avenue du Col Rol-Tanguy – with the basement its stark, evocative centrepiece.

“Fewer and fewer of the generation who were directly involved can now pass on their story,” said Sylvie Zaidman, the museum’s director. “This is about helping today’s public to understand and reflect on a fundamental page of France’s history.”

Soon, Zaidman added, there will be “no more former résistants – but they have left us their testimony, and fragments of each of their extraordinary stories. It’s now our responsibility to make sure everyone understands that it’s our history, too.”

A pet project of Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo, the Musée de la Libération de Paris - Musée du Général Leclerc - Musée Jean Moulin, opens on the 75th anniversary of the capital’s liberation after four years and €20m of work, opposite the city’s famous catacombs.

It tells the parallel stories of two towering French wartime figures: the courageous young official Jean Moulin, charged by De Gaulle with unifying domestic resistance; and Philippe Leclerc de Hautecloque, the brilliant soldier who joined the Free French in London and, as General Leclerc, fought through Africa before landing in Normandy and leading his 2nd Armoured Division to Paris.

“They never actually met, and they were very different people,” said Zaidman. “But when France fell in 1940, they made their choice – they would continue the fight, one inside their homeland, and one outside. Their common objective was France’s liberation, with a liberated Paris its greatest symbol.”

Replacing a little-known and chaotically organised exhibition above Montparnasse station, the museum brings together artefacts from the lives of both men bequeathed and donated by relatives, plus maps, photographs, interviews, archive footage and intimate, everyday objects from occupied Paris, to tell a new, focused and hugely powerful story of the second world war in and beyond the French capital.

Visitors are taken from the tense foreboding of the interwar period through the great exodus of June 1940, when three-quarters of the city’s population fled, and the four grinding years of occupation, to the brutal rounding up and deportation of the city’s Jews, the myriad petty betrayals of collaboration and eventually, to the rise of the resistance and the bitter street battles of the five-day insurrection.

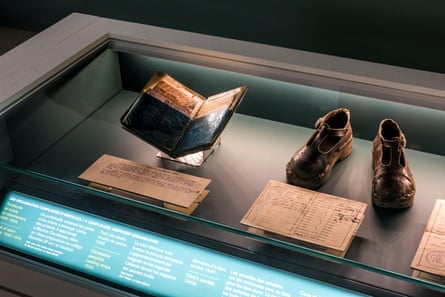

Everywhere, objects startle: Moulin’s skis and box of pastels; the matchbox in which he hid his microfiched orders from De Gaulle; paintings from the art gallery he ran in Nice as cover; the suitcase he carried when he returned to France from London for the last time, in March 1943, before his arrest, torture and eventual death.

“That may be my favourite,” said Hanna Diamond, an expert on the second world war from Cardiff University and the only British historian on the museum’s advisory committee. “There’s mystery there – we believe it may have something concealed in the handle, but it’s too fragile to take apart or even X-ray.”

Of Leclerc, there is the walking cane he was never without, a woollen burnous from his Moroccan campaign, the British identity papers he was issued with for his time in London, American army kit donated to his Free French forces.

But it is the small items of everyday Parisian life that speak loudest: propaganda, even in children’s games; a schoolboy’s wallet filled with ration cards; a yellow star; a tiny wooden-soled child’s shoe (leather was in short supply); a note denouncing “Anglo-Gaullist-Jewish” neighbours; a hand-drawn map, typewriter, and radio used by the resistance; a dress stitched in red, white and blue for liberation day; a letter by nine-year-old Ginette describing the scenes on 25 August.

“The aim was to be as engaging and as accessible as possible,” said Diamond. “To tell the story clearly and evocatively for an audience who are not necessarily familiar with it and may not fully understand the context. To be logical, and pedagogical – there’s a real republican responsibility here.”

The museum’s potency is greatly enhanced by the fact that “it all actually happened here”, Diamond said.

Nowhere is that resonance more powerful than in the basement. Down 99 steep steps and through a set of heavy steel airtight doors to guard against an eventual gas attack, the vast, echoing corridors and rooms have been restored to their wartime state after decades of neglect and the enthusiastic attentions of generations of graffiti artists.

The remains of Rol’s vital telephone exchange, which put the resistance commander in direct contact with the police and city authorities, bypassing the official, Nazi-run communications network, are there, plus a remarkable cycle-powered electricity generator that could also be used to remove C02 from the complex.

Visitors to the museum will be able to tour the resistance command post in small groups with “mixed reality” headsets playing footage from a black-and-white documentary shot in the basement soon after the liberation, in which Rol and other resistance leaders recount their five days spent underground.

“Of course, it nearly didn’t happen,” said Zaidman. “The Allies weren’t interested in liberating Paris. It wasn’t strategic. It meant street fighting, feeding a population. But for De Gaulle it was fundamental, symbolically crucial. And in the end, the French were allowed to liberate Paris. After the trauma of defeat and occupation, it was a fundamental moment for France. We hope we’ve done it justice.”