The Bengal famine of 1943 was the only one in modern Indian history not to occur as a result of serious drought, according to a study that provides scientific backing for arguments that Churchill-era British policies were a significant factor contributing to the catastrophe.

Researchers in India and the US used weather data to simulate the amount of moisture in the soil during six major famines in the subcontinent between 1873 and 1943. Soil moisture deficits, brought about by poor rainfall and high temperatures, are a key indicator of drought.

Five of the famines were correlated with significant soil moisture deficits. An 11% deficit measured across much of north India in 1896-97, for example, coincided with food shortages across the country that killed an estimated 5 million people.

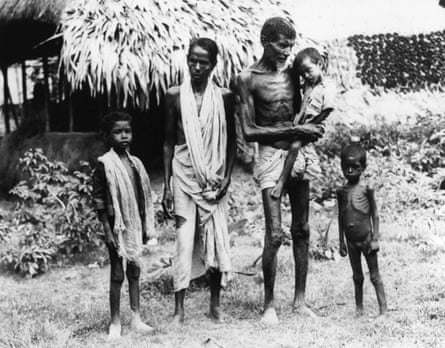

However, the 1943 famine in Bengal, which killed up to 3 million people, was different, according to the researchers. Though the eastern Indian region was affected by drought for much of the 1940s, conditions were worst in 1941, years before the most extreme stage of the famine, when newspapers began to publish images of the dying on the streets of Kolkata, then named Calcutta, against the wishes of the colonial British administration.

In late 1943, thought to be the peak of the famine, rain levels were above average, said the study published in February in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“This was a unique famine, caused by policy failure instead of any monsoon failure,” said Vimal Mishra, the lead researcher and an associate professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar.

Food supplies to Bengal were reduced in the years preceding 1943 by natural disasters, outbreaks of infections in crops and the fall of Burma – now Myanmar – which was a major source of rice imports, into Japanese hands.

But the Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen argued in 1981 that there should still have been enough supplies to feed the region, and that the mass deaths came about as a combination of wartime inflation, speculative buying and panic hoarding, which together pushed the price of food out of the reach of poor Bengalis.

More recent studies, including those by the journalist Madhushree Mukerjee, have argued the famine was exacerbated by the decisions of Winston Churchill’s wartime cabinet in London.

Mukerjee has presented evidence the cabinet was warned repeatedly that the exhaustive use of Indian resources for the war effort could result in famine, but it opted to continue exporting rice from India to elsewhere in the empire.

Rice stocks continued to leave India even as London was denying urgent requests from India’s viceroy for more than 1m tonnes of emergency wheat supplies in 1942-43. Churchill has been quoted as blaming the famine on the fact Indians were “breeding like rabbits”, and asking how, if the shortages were so bad, Mahatma Gandhi was still alive.

Mukerjee and others also point to Britain’s “denial policy” in the region, in which huge supplies of rice and thousands of boats were confiscated from coastal areas of Bengal in order to deny resources to the Japanese army in case of a future invasion.

During a famine in Bihar in 1873-74, the local government led by Sir Richard Temple responded swiftly by importing food and enacting welfare programmes to assist the poor to purchase food.

Almost nobody died, but Temple was severely criticised by British authorities for spending so much money on the response. In response, he reduced the scale of subsequent famine responses in south and western India and mortality rates soared.

Though India’s population has vastly increased since the British colonial era, the country has largely eliminated famine deaths owing to more efficient irrigation practices, improvements in seed yields, a stronger food distribution and welfare system and better transport links, which allow emergency food stocks to be moved quickly to deprived areas.