Have you ever attended a trade fair? There’s one for most industries and interest groups. A list of events scheduled at London’s ExCeL Centre this year, which may or may not go ahead because of the Covid-19 pandemic, include: Intelligent Building Europe, The Call & Contact Centre Expo, Oceanology International, The European Pizza & Pasta Show, and, of course, a Comic Con.

Should you attend such an event, you would be forgiven for thinking little of its architectural setting. There are of course exceptions, but most modern exhibition centres consist of windowless sheds which serve as stage sets for the exhibitors’ stands. They are typically navigated by vast alphanumeric grids, which have you trotting endlessly without the general vista changing much. A73 in Hall B looks exactly like F26 in Hall A, only with a different type of pasta on show, or a new tool for oceanographic exploration. This is the point of such spaces. They are highly serviced, highly adaptable, and highly boring-looking.

It is sometimes difficult to conceive of a convention centre as a single complex, so embedded can it be in its ancillary infrastructure. Venues often have their own train stations (the Köln Messe stop for Cologne’s main halls; the Rho Fieramilano station for Milan’s enormous expo complex) which help shuttle visitors in the tens of thousands from nearby airports directly into the venue. London’s ExCeL sits right next to its City Airport. In Las Vegas, one of the US’s trade show capitals (the Strip alone boasts a staggering 10.5 million square feet of exhibition space), halls are attached to resorts and casinos, with distinctions between any of these spaces, between leisure and commerce, thoroughly obscured.

It is nonetheless a recognisable typology, with roots in the earliest World Exhibitions of the mid-to late-19th century. London’s Crystal Palace, which was built in Hyde Park to host the first such event, the Great Exhibition of 1851, was a precursor to today’s NECs, ExCeLs and Javit Centers. The technologies used to construct it – notably cast-iron and sheet glass – were part of the British Empire’s display of industrial prowess at the time. Crystal Palace accommodated more than 14,000 exhibitors and welcomed some six million people during its five-month run. Today’s convention centres have a quicker turnaround of trade shows (often weekly), and have adapted their services and infrastructure accordingly. The 1980s and 90s in particular, shows Heywood Sanders in his 2014 book Convention Center Follies, was a time when many new purpose-built convention centres were erected, occasioned, in part, by accelerating globalised trade, cheap international travel, and local governments eager to invest in venues promising a boost in commercial activity.

Today, these spaces are being put to new use. At the beginning of 2020, convention centres around the world began to be repurposed to help cities cope with the escalating Covid-19 pandemic. Early on, the China Optics Valley Convention & Exhibition Center in Wuhan, the epicentre of the pandemic, was reportedly transformed into a 1,000-bed hospital in just 24 hours. Other countries followed suit: the Bashundara Convention Centre in Dhaka, Bangladesh; the Durban International Convention Centre in South Africa; the Centro de Convenciones Bicentenario in Ecuador; and the Javits Center in New York City, one of the US’s worst hit areas, being only some of the venues transformed into makeshift medical facilities at breakneck speed. In England, seven NHS Nightingale Hospitals were adapted from existing venues into critical care hospitals in March and April. The two largest ones, in Birmingham and London, prepared temporary hospitals with the capacity of 4,000-5,000 beds within the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) and the ExCeL respectively.

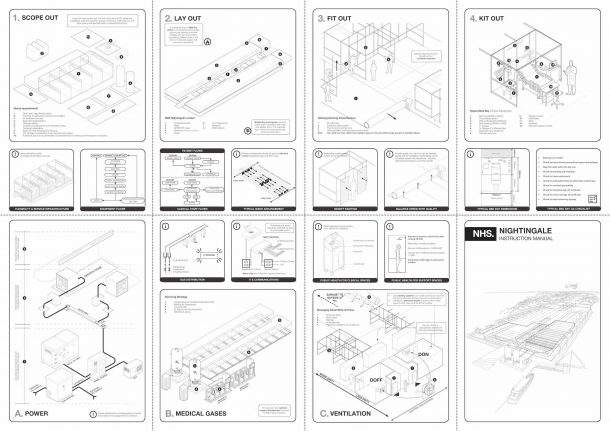

Nightingale London in the ExCeL was built in just nine days with the help of Royal Anglian Regiment and Royal Gurkha Rifles alongside NHS staff and contractors, officially opening on 3 April 2020. Nightingale Birmingham in the NEC followed a fortnight later. The speed at which this happened is testament to the enormous effort put in by all involved, but also to the sheer malleability of the convention centre space. BDP, the architecture firm tasked with designing the Nightingale Hospitals, published an instruction manual setting out some of the main principles of converting exhibition centres (or any “large barn type spaces”) into hospitals. Venue requirements, it says, include a “clear span, large flexible space,” “proximity to appropriate staff accommodation”, “space for medical gases”, and “general parking”, all of which were readily at hand at the ExCeL and NEC. It stresses the importance of using existing infrastructure, including “exhibition stand systems” for building bed bays, and seeking assistance from “available workforce from events sector”.

“Both the NEC and the ExCeL used exhibition stand systems,” says Max Martin, an architect director at BDP who worked on the Nightingale project. “Those systems were quite simple because they’re rectilinear, they clip and click together, and we could make them work for the sizes of the bays.” Ventilation, at least at the NEC, was also deemed to be sufficient for the purposes of a temporary hospital. “Because they’re large, voluminous spaces that are typically used to having large numbers of people in them, they do have quite high air change rates,” says Martin. “I guess that’s an inherent value to that kind of space.”

Other aspects were more challenging. Exhibition centres generally have high electrical capacity, given the events they support, but hospitals require not only capacity, but “electrical resilience,” explains Martin. Backup generators needed to be put in place to make the spaces more compliant. In addition, the delivery of medical gases – particularly oxygen – was an especially gnarly problem. The plumbing for oxygen supplies comes with its own specific fire risks and would normally take many weeks to lay out. “You also need enough space to put up big gas tanks,” says Martin. Finally, there was the issue of delivering hot water to an unprecedented number of individual points. “One of the big things with Covid-19, and with hospitals generally, is that you’ve got to wash your hands a lot. With thousands of beds that involves lots of hand-wash basins.” A schematic design for a portable basin unit can be found in the BDP’s instruction manual. “HOT WATER IF POSSIBLE,” reads the diagram.

It is now late May, and while Nightingale London took in a small number of patients in its first weeks, the demand has not been as high as originally anticipated. At the beginning of the month, it was announced that most of the facilities would be mothballed and effectively put on standby, should they be needed in the event of a second wave. “The purpose of all these buildings was to provide capacity should it be needed,” says Martin, “and I suppose it’s a positive thing that it’s not been needed in quite the way it was thought.”

While the Nightingales lie dormant, and mass gatherings remain out of the question, convention centres around the world are facing hard times. “We went from a very busy, active convention center to zero,” said Dieter Heigl, the general manager of a large Chicago exhibition space, to the Daily Herald this month. “It certainly is the most challenging environment I’ve encountered in my career.” When will we have our trade shows and comic cons back? Do we want them back at the same fervent rate? For several years now, the European design industry’s main trade event, the Salone del Mobile in Milan (held at the Fiera Rho), has been subject to critique. There are arguments for slowing down – industry is overheating, producing new stuff for the sake of new stuff, and it’s far from sustainable. The industrial designer Hella Jongerius and academic Louise Schouwenberg launched a manifesto titled ‘Beyond the New’ at the 2015 edition of Salone. “What most design events have in common,” they wrote, “are the presentations of a depressing cornucopia of pointless products, commercial hypes around presumed innovations, and empty rhetoric”.

Convention centres converted into hospitals: it’s a powerful image of the way in which many sectors of the global economy have ground to a halt in the wake of the virus. The very buildings geared towards facilitating international trade have now been recalibrated for care. It is, perhaps, a time to pause and consider how we want to inhabit these spaces once this pandemic is over.

Related objects from the collections:

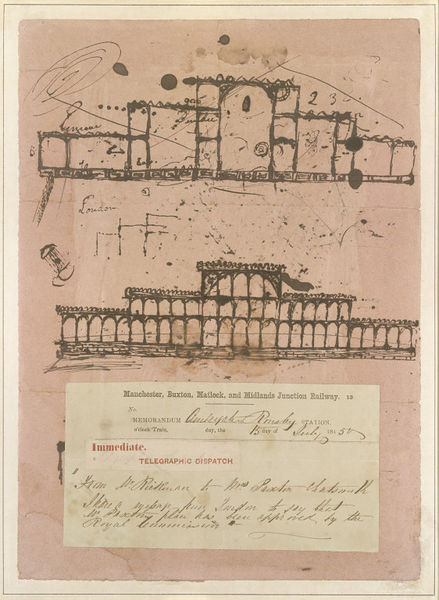

The Great Exhibition building (architectural sketch)

Joseph Paxton

Derby, UK

1850

E.575-1985

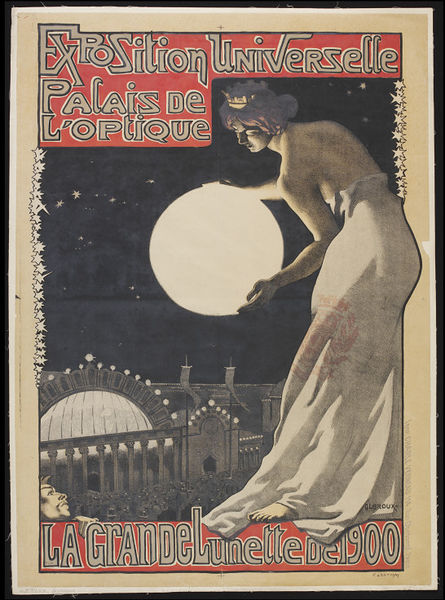

Poster advertising the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle

Georges Paul Leroux

France

1900

E.423-1939

E.423-1939 Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum

Further reading:

‘How to Set Up an ICU’, Lana Spawls, , London Review of Books, Vol. 42 No. 8, 16 April 2020.

‘Beyond the New’, Hella Jongerius and Louise Schouwenberg, 2015.

Heywood T. Sanders. Convention Center Follies: Politics, Power, and Public Investment in American Cities. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Christopher van Uffelen. Convention Centers. Braun, 2012.